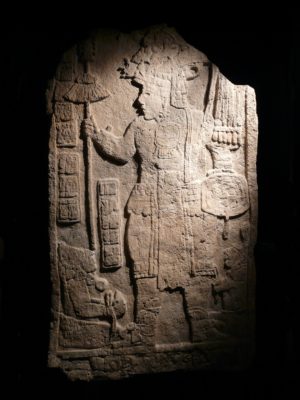

King Yuknoom Took’ K’awiil, Stele 51, Calakmul, Campeche, Mexico, 731 C.E. (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Kings in stone

In 1839, American lawyer and amateur archaeologist John Lloyd Stephens and English artist Frederick Catherwood were the first outsiders to venture into the rainforests of Central America. They brought back their romanticized accounts and drawings of the remains of ancient Maya civilization to an eager England. In their publications, Stephens and Catherwood conveyed that they had uncovered the ruins of a great civilization that was uniquely American—one that had developed without contact with Egypt, India, or China.

Solemn and “strange”

Among the many “strange” and wonderful sites they encountered, it was the monuments that most aroused their interest and sparked their Victorian sensibility for engaging past civilizations. In regard to these hefty carved stones, Stephens penned the following excerpt,

standing as they do in the depths of the forest, silent and solemn, strange in design, excellent in sculpture, rich in ornament…their uses and purposes and whole history so entirely unknown….[1]

Over the past thirty years, scholars have made substantial advances in understanding the “uses and purposes” of Maya stone sculptures, and of the ancient peoples that produced them. This progress is due in no small part to developments in the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphics, which has escalated in recent decades. Epigraphers and art historians have labored to reconstruct the history and culture of the flourishing Classic period expressed on the sculptures found throughout México, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Belize.

We now understand that the sculptors who chiseled these monuments were commissioned by privileged elites who lorded over vast city-states. These regional political and geographic partitions were dominated by singular powerful city-centers that vied for control of land and resources. Such cities were immense, and within them, architects built grand pyramids and temples embellished with sculptures. Sculpted stone was an enduring record, and as early explorers witnessed, the remains of hundreds of carved monoliths still grace the ruins of these ancient Maya cities.

A medium for political and religious rhetoric

Portrait of ’18-Rabbit’ from Stela A, Copán, Honduras, 731 C.E. (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The stone monuments over which Stephens and Catherwood marveled were crucial to the social and political cohesion of ancient Maya city-states. While small-scale art objects were cloistered behind the walls of privileged homes and courts, larger stone sculptures served as the principal medium for presenting political and religious rhetoric to the public.

The most vital and imposing format was the stela—an upright flat slab of stone worked in relief on one, two, or four faces. Their placement at the base of immense pyramids or in open plazas facing small stage-like platforms suggests that they were intended to be viewed by vast audiences in conjunction with other public spectacles. These lakam-tuun (banner stones) conveyed a broad and complex set of ideologies concerning royal history and politics, ceremonial activity, and calendrical reckoning. Their just-over human scale renders them ideal for presentations of engaging and awe-inspiring ruler portraits. In the tense political atmosphere of the Classic period, enduring images of powerful leaders ensured that the public recognized the authority of the ruler, the fortitude of his or her dynasty, and of the favor of deities.

Iconography and text carved onto stelae illuminated the king’s visionary power. Contemporary notions of idealization prescribed that rulers appear youthful, handsome, and athletic. They wore a vast inventory of authoritative garb that included jade ornaments, various symbols of kingship, and an unwieldy, oversized headdress that must have been highly impractical for regular use. These figures act out one of a standard set of rites of passage: they wear battle garb to emphasize their military prowess, ritually let blood in offering to the deities, “scatter” sacred substances with outstretched hands, or participate in ritual dance. Imagine trying to dance while balancing a headdress that is half your own height! Accompanying hieroglyphic texts elaborated on the life of the ruler and his ancestors.

Portrait of King Tahn Te’ K’inich in the garb of a warrior from Stela 6, Aguateca, Guatemala, ruled 770–802 C.E. (Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, Santiago; photo: Bkwillwm, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The conquering ruler

As regional conflicts became more frequent in the 8th century, military themes on portrait stelae increased.

Stela 6 from Aguateca, Guatemala, exemplifies the archetype of the conquering ruler, responsible for defeating enemies and procuring captives for ritual sacrifice. Although the hieroglyphs on this monument are eroded, the portrait appears to depict King Tahn Te’ K’inich as he brandishes a spear and shield and stands victoriously over two bound enemy captives.

Although Classic-period Maya stelae are no longer shrouded in mystery, numerous questions remain in regard to how they functioned. Perhaps most importantly, they provide only one side of the story, that of the ruler and of royal ideology. Stelae offer us little information regarding how they were received by the public, and we can only guess how effectively they impacted the common person. Although we know far more about ancient Maya stelae than Catherwood and Stephens ever imagined possible, the haze of mystery and intrigue through which they viewed these monuments has hardly evaporated.

Notes:

[1] In Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, by John Lloyd Stephens (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993).

Additional resources

Read more about this time period in a Reframing Art History chapter on Mesoamerica.

Maya Art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

2004 Exhibition Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya at the National Gallery of Art.