From a live webinar with Dr. Beth Harris. Discussion of strategies for finding high-quality images starts at 16:00.

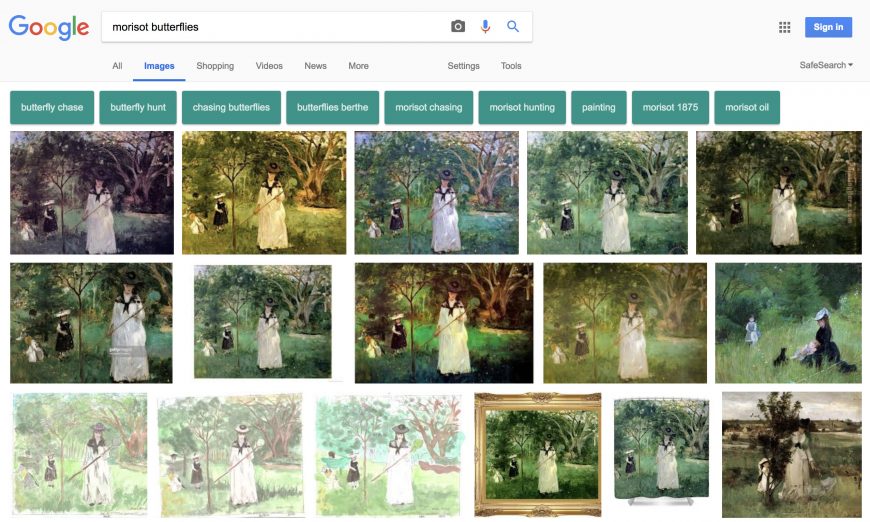

Image search is one of the most important aspects of producing a good video, and it takes a huge amount of time. The wide availability of images on the Internet can be deceptive—as you can see in the example above, though image quantity may be large, image quality varies greatly.

Even if you already have good photographs from your recording session, you’ll need other images to demonstrate things like comparisons and historical context.

It is quite normal for us to spend hours looking for one high-quality image online. We’ve found that if we do not spend enough time on image search, the quality of our final product will be adversely impacted.

Jump to

- What to look for

- Image quality

- Image provenance and attribution

- Where to look for images

- Additional image resources

What to look for

As you look for images, you will want to keep three things in mind:

- image quality

- identifiable provenance of the work

- rights and attribution

What should I look for in terms of image quality?

The first thing to look for is high resolution.

- The image should be at least 1000 pixels on the maximum dimension, preferably much more

- It should not be a scan from a book

- It should not have a watermark or author name in the image

You should also look for images with properly adjusted color, framing and without reflections or shadows. If needed, you can crop out margins or parts of the frame that show unevenly, and edit the photo for color or other small issues. However, it is best to start with the highest-quality image possible.

Example of a bad reproduction:

Berthe Morisot, Hunting Butterflies, 1874, oil on canvas, 46 x 56 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris, photo via WikiArt.org)

This image is small (only 731×600 pixels, not large enough for video), and is neither sharp, nor is the color correctly adjusted.

Example of a good reproduction:

Berthe Morisot, Hunting Butterflies, 1874, oil on canvas, 46 x 56 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This image is high-resolution (4918 × 2767 pixels), and has been photographed properly. The color looks true to the work of art and everything is sharp. If you don’t want to show the frame, you can always crop the photo in Photoshop or your video editing software.

Image provenance and credits

It is very important to be able to identify the location of whatever work you show, and to properly list this information in your video.

Tip: in Smarthistory videos, we show limited caption information alongside the images themselves (usually only artist, title, and date). We list the full caption information, including image rights and links, if applicable, in the end credits (in the order of appearance, so the image can be easily located).

For works of art, this information is usually easy to find through the museum or other institution where the work is housed. You can simply credit it by listing the caption information as it might appear on a placard:

| Berthe Morisot, Hunting Butterflies, 1874, oil on canvas, 46 x 56 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) |

Texts, plates from texts, and historical photographs can also be credited this way, but be sure that you can identify the source (such as a library, archive, or similar):

| Charles Marie de la Condamine, An Abridged Account of a Journey Made in the Interior of South America (Relation abrégée d’un voyage fait dans l’interieur de l’Amerique méridionale), 1745 (John Adams Library, Boston Public Library)

Alexander von Humboldt, Chimborazo Seen from the Tapia Plateau, Ecuador, hand-colored engraving, in Vues des Cordillères et monuments des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique, 1810 (British Library) Detroit Publishing Company, Bird’s-eye view of Pennsylvania Station, New York City, c. 1910-20, glass negative, 8 x 10 inches (Library of Congress) |

If the work is three-dimensional, or if you are using a recently-created photograph of a gallery, building, or event, then you need to also be sure to list the author and license, and link to the image if possible. Note that many online authors have unconventional usernames, and that listing them as such is standard and acceptable:

| Donatello, Saint Mark, 1411-13, marble, 236 cm, Orsanmichele, Florence (photo: Mongolo1984, CC BY-SA 3.0) <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:San_Marco_di_Donatello,2.JPG>

Church of Saint-Sulpice, Paris, begun 1646, completed 1870 (photo: photomanthe2nd, CC BY-SA 3.0) <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Sulpice_Cathedral_-_panoramio.jpg> Aerial view of looting at Cerro Sapame, Lambayeque region, 1978 (photo: Dr. Izumi Shimada, used with permission) |

Where to look for images

A good place to start is Google Images, but keep in mind that images from many image libraries, museums, archives, and other quality resources will not show up here. In other words, spending 10-15 minutes on a Google image search may not turn up academic sources, and this is especially true for images that are more rare. Also, even if your image turns up in a Google search, there could well be a better reproduction from a library, museum or archive.

Tip: Right-clicking on any image in the Chrome browser and selecting “Search Google for image” will automatically result in an image-based search in Google Images. You can also use the “tools” function to help sort by size and find larger images and search for works that are licensed for reuse.

A word about Pinterest…

Many Google Image search results will lead you to images on Pinterest. These are very rarely linked to accurate metadata (the important caption and attribution information about an image), and so it is impossible to find out where the image is from or what rights it has been assigned. You should avoid using images directly from Pinterest, but you can sometimes use Pinterest to help you determine whether an image exists. Find the images you want to use on reliable, data-rich websites instead.

Collection websites

Look at the collection site for the museum where the object is housed. The museum may have a high-quality image available for download. Be sure to check what rights they have assigned to the image.

Wikimedia Commons (the media repository linked to Wikipedia) has a huge wealth of images, though the quality varies. Sometimes it is easier to find things on Wikimedia Commons by first searching for the work or artist in Wikipedia. A link to related Wikimedia content is usually included at the bottom of the page.

Flickr is an especially good source for CC-licensed images of three-dimensional works. Make sure you filter your search accordingly using the “advanced search” options.

Google Maps allows the use of screenshots, as long as the Google logo and credit remain visible. See here for more information on Google Maps permissions and attribution requirements.

This tool searches across several sites for Creative-Commons licensed images.

An important tool for searching across European collections.

Frequently asked question: Why not Artstor?

Generally, the images housed in Artstor are not licensed for reuse. Though you may use them for classroom teaching, even if the artworks reproduced in Artstor images are in the public domain, the ARTstor agreement does not allow for reuse outside the classroom. However, you can use the images in the ARTstor Shared Shelf Commons.

Additional image resources

Here are some additional sources that contain images licensed for reuse. Remember to always double-check the license for any image you find.

Museums

Libraries and archives

- Bibliotheque Nationale de France/Gallica database

- Library of Congress

- David Rumsey historical map collection

- John Carter Brown Library (Brown University)

- National Archives

- British Library

- New York Public Library digital collections

Manar Al-Athar

Aggregators (sites that pull data from many institutions)

- Google Cultural Institute

Creative Commons - Europeana

- Digital Public Library of America

- Archive.org

- World Digital Library

- Digital Commonwealth (Massachusetts collections online)

Photography repositories