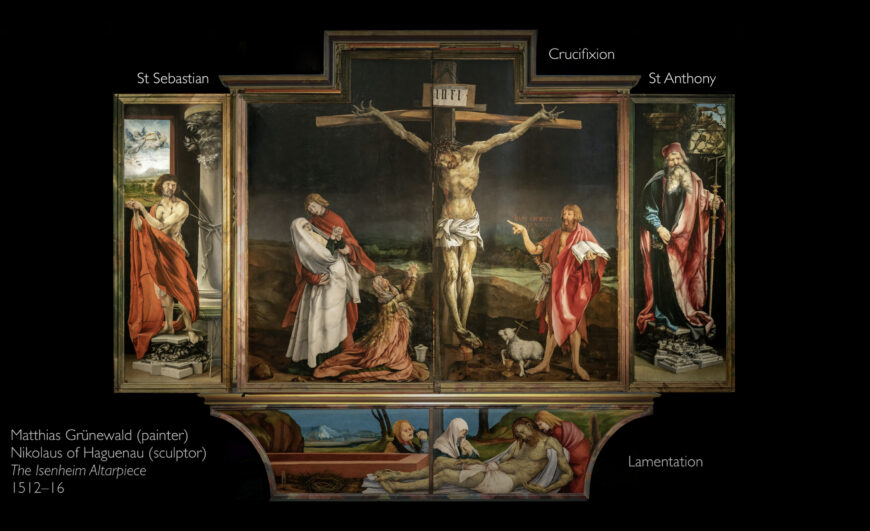

Mathis Nithart (or Gothart), known as Matthias Grünewald (painter), Nikolaus of Haguenau (sculptor),

The Isenheim Altarpiece, 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Musée Unterlinden,

Colmar, France) speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:06] We just walked into a gallery at the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar, France. We’re close to the German border. [We’re] looking at a massive series of paintings. This is “The Isenheim Altarpiece,” by Matthias Grunewald.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:18] What we’re looking at is an astounding triple transforming altarpiece.

Dr. Zucker: [0:25] Winged altarpieces would remain closed for much of the year. They would be opened on special feast days.

[0:31] Of course, museum visitors want to be able to see everything, so what the museum has done is to take the dismantled altarpiece and to set it up as a series of panels that you walk through.

Dr. Harris: [0:41] This altarpiece once stood in a church that was part of a monastery dedicated to St. Anthony, whose relics had recently been brought to this area and were said to have performed a miracle, curing a disease known as ergotism.

[0:56] Soon after, a brotherhood was established to care for those with this disease. These monasteries, essentially hospitals, spread across Europe. Ergotism is a terrible disease that caused gangrene, convulsions, all sorts of horrific symptoms.

Dr. Zucker: [1:13] When you look at the paintings that make up the Isenheim Altarpiece, the idea of suffering and then the idea of redemption is clear, so its placement in a hospital makes sense. We’re here on Good Friday, so it’s appropriate that we’re seeing first the large central image of Christ on the cross.

Dr. Harris: [1:33] What we notice immediately is the way that his body has been marked by wounds, by lesions, by thorns. This is a body that is suffering on every inch of its surface.

Dr. Zucker: [1:46] Look at the crown of thorns, the way it pierces his left shoulder. Christ’s lips are blue, his mouth is open, his teeth revealed. The eyes are closed, the side of his head is horizontal; his hips stretch downward, thinning his abdomen. Look at the hands that are nailed into the cross, the way that the fingers seem stiffened and push out in every direction.

[2:08] His body is covered by lesions that art historians have suggested reflect the way that ergotism wracks the human body.

Dr. Harris: [2:16] St. John has his right arm around Mary to support her. That arm is elongated. Grunewald is not concerned with correct anatomy. What he’s thinking about is the mystical power of the moments that he’s representing. Mary’s hands are clasped, her eyes are closed, her mouth is slightly open. She is white as death, watching her son die.

Dr. Zucker: [2:41] We see Mary Magdalene. She’s identified because she’s closer to Christ’s feet. Her reddish hair is quite long and she has a jar of ointment beside her. On the opposite side, John the Baptist is shown pointing to Christ, with the Lamb of God at his feet.

[2:57] The Lamb is holding a cross and bleeding from a wound — that echoes the wound that we see on Christ on the cross — into a golden chalice.

Dr. Harris: [3:05] The idea of Christ as the lamb that is sacrificed for the sins of mankind.

Dr. Zucker: [3:11] The Lamb’s face points us to the hideously distorted feet of Christ nailed to the cross, where we see a kind of malformation of the human body that expresses the intensity of the suffering.

Dr. Harris: [3:23] Saint John points to Christ because he’s, in a way, a forerunner of Christ. He’s baptizing people in the River Jordan. We see a river behind him.

Dr. Zucker: [3:32] All of this is brought together against a dark landscape and a leaden sky. That sky is a series of rich grays that have an almost purple tint to them. Saint Sebastian occupies the leftmost panel.

Dr. Harris: [3:46] Saint Sebastian was killed for his faith in Christ.

Dr. Zucker: [3:51] We can see angels with a golden crown.

Dr. Harris: [3:53] This idea of the crown of martyrdom, that even though he suffered on Earth, he’s triumphant in heaven.

[4:00] On the right, we see Saint Anthony; he holds the Tau cross. He’s depicted larger than Saint Sebastian, which makes sense because of his status as patron saint. Like Saint Sebastian, he stands on a plinth decorated with sculpted foliage that seems to be growing as we look at it.

Dr. Zucker: [4:20] In the upper right corner, there’s a demon visible through a window. This is a reference to the temptation of Saint Anthony that is treated more completely in a panel within the altarpiece.

[4:30] Below the Crucifixion, there’s yet another scene. Here we see the Lamentation. We see the dead Christ being mourned beside his tomb.

Dr. Harris: [4:38] His body is being supported by Saint John. We also see Mary Magdalene at the far left, her hands clasped, her mouth open, expressing her grief. We see Mary, Christ’s mother, shrouded in white against this deep blue sky.

Dr. Zucker: [4:54] But mostly what I see is the tortured flesh of Christ. Every inch of his body has been marked. His feet are torn and distorted. His hands are extended. The curves that define his body express his lifelessness.

Dr. Harris: [5:10] When the altarpiece is opened to its next stage, we see four individual scenes. The Annunciation [is] on the left. The next scene is called the choir of angels. Then we see the Nativity, and on the right, the Resurrection.

[5:25] In the Annunciation panel, we see the angel Gabriel announcing to Mary that she will bear the Christ Child, that she will be the mother of God. That happens through the Holy Spirit, who we see in the form of a dove, surrounded by a glowing halo.

[5:42] We seem to be in a church-like space with groin vaults, articulated with greens and reds and Gothic windows in the background. Mary kneels, indicating her humility. She’s studying the Bible. There are books around her, and she accepts the words of the angel Gabriel with great humility.

Dr. Zucker: [6:04] It seems as if Gabriel has just alit. It’s as if he has only one foot down. His drapery is still aflutter. Gabriel points to the Virgin Mary. Her head is tilted as if in response to the power of his message. Look at the delicacy of her golden hair and the expressiveness of her hands.

Dr. Harris: [6:22] This is the moment when God is made flesh. Grünewald is expressing visually the theological import of this moment.

Dr. Zucker: [6:31] The central double panel with a choir of angels and the Nativity is, for me, the most complex. On the left, we see Gothic architecture, a kind of open-air porch occupied by musical angels.

Dr. Harris: [6:44] We see an astounding number of figures, some coming out of the atmosphere in reds and blues. We see figures who we presume to be sculpted figures as part of the architecture coming alive and conversing with one another. It’s as though the entire universe is activated by this celebration that God has been born in the form of a human being to save mankind.

Dr. Zucker: [7:12] We see an angel playing a stringed instrument with a bow. We see a female figure wearing a crown, this brilliant yellow-orange-red nimbus that emanates from her head, and she points us to the scene adjacent. But before we follow her invitation, let’s take a look at one of the other angels that’s set back in shadow.

Dr. Harris: [7:31] On the far left, we see an angel with wings, also playing an instrument. His skin is greens and yellows and grays, as though he himself is sickly, with black fingernails, suggesting death. The figure wears, importantly, a peacock’s crest, a symbol of pride, of vainglory. This figure has been identified as Lucifer, as the devil.

[7:58] The idea of including Lucifer seems odd among this choir of angels. But according to Christian thought, the devil is an angel who, through his pride, has fallen from grace with God. It’s the devil who can claim the souls of all human beings until Christ is born, until God hides divinity within the flesh of a human being, tricks the devil, and makes it possible for mankind to have salvation.

[8:29] This is possibly this moment when Lucifer recognizes that he’s been tricked.

Dr. Zucker: [8:35] It’s important to recognize that in such a complex series of paintings, telling such a complex series of stories, multiple interpretations are possible. In fact, the artist and the patron may have intended multiple interpretations. There may not be a single meaning in each element of the painting.

[8:52] The right side of the panel seems almost out of scale. The figures are significantly larger. The Virgin Mary and Christ Child are depicted in an enclosed garden. This careful rendering of roses are beside them. The Virgin Mary’s head tilts down. She looks at the Child. The Child looks back up at her and playfully handles a rosary.

Dr. Harris: [9:12] The rosary beads were an aid to prayer. These are made of coral, which symbolize Christ’s sacrifice, his blood. The idea here is warding off of evil. We know that evil is nearby because we’ve seen the devil in the panel to the left.

[9:31] I really like the way that Mary isn’t just holding Christ on her lap, but has lifted him up so that their faces come together. The foliage and the rosebush reminds me of this Northern Renaissance tradition with this very careful, detailed rendering of grass and flowers and foliage.

[9:51] At the same time, the backdrop is this mountainous landscape that is rendered in these icy blues, so different than the colors in the foreground, and seems to almost dissolve into the atmosphere.

Dr. Zucker: [10:07] If you look very closely, we see this majestic rendering in yellow-white of God the Father in heaven. He holds a scepter and an orb with a cross above it. He’s surrounded by a multitude of angels, some of whom fly down from the heavenly into the earthly sphere.

Dr. Harris: [10:24] Some of these angels are golden. Some of them, though, are darker orange and even bluish purple.

Dr. Zucker: [10:30] There’s such a striking contrast between the luxurious clothing that the Virgin Mary wears and the tattered rag that she holds below the Christ Child.

Dr. Harris: [10:40] This tattered cloth is reminiscent of the one that Christ wears during the Crucifixion. We have this connection between Christ’s childhood and his terrible future.

Dr. Zucker: [10:51] The rightmost panel jumps forward in time. This is the Resurrection. Here we see the purpose of all the suffering that has been expressed thus far.

Dr. Harris: [11:00] This is the moment when that sin of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden is reversed and mankind has the possibility for immortality, for life in heaven after death, and Christ has exploded out of his tomb.

Dr. Zucker: [11:14] This is a kind of cosmic fulfillment. Here Christ is set against the night sky, with this orb of light that emanates from him, so much so that his very body seems to be almost obscured by the light that is emanating from it.

Dr. Harris: [11:30] He’s become ethereal. He holds up his hands so that we can see the wounds from the Crucifixion, but they are no longer painful.

Dr. Zucker: [11:37] His head is no longer down as it was in the crucifixion. He looks directly at us, forthright. Light is emanating from his wounds.

Dr. Harris: [11:46] All of that suffering leads to this moment of release from pain, release from the suffering of the body and life in the paradise of heaven.

Dr. Zucker: [11:57] Imagine how powerful that message would be in this hospital where people are suffering, where their bodies are tormented. The brilliant yellows that emanate from Christ’s face give way to these beautiful orange and then red tones. Those then give way to these blues that bring us down to the bottom of the panel.

[12:17] Here we see the Roman soldiers whose job it was to guard the sepulcher, that is to guard the tomb that held the body of Christ. Here, they have been thrown over by the power of his resurrection.

Dr. Harris: [12:28] The tomb has opened, Christ has arisen. This is not like any other moment in time. This is an explosion of the divine into this earthly sphere, and we have a really palpable sense of this unprecedented moment.

Dr. Zucker: [12:46] Look at how their bodies are defined by the light that emanates from Christ. Although this is a night scene, they are illuminated from above. This altarpiece is remarkable in that it has three levels, and when the second set of panels is opened, we’re treated to the final group of images.

Dr. Harris: [13:01] We arrive at a combination of painting and sculpture, which was not at all unusual for altarpieces in northern Europe.

Dr. Zucker: [13:09] The sculpture is actually the oldest part of this altarpiece. It was produced by another artist, Nikolaus Haguenau, who was renowned for these polychromed and gilded wooden sculptures, these figures that are so lifelike. Anthony is enthroned in the center and he’s surrounded by two Church Fathers.

[13:27] The two Church Fathers both look inward, but Anthony, seated in the center, looks directly out at us.

Dr. Harris: [13:34] Well, it’s Anthony who’s associated with healing this disease, which became known as St. Anthony’s Fire. He is the key miracle-working figure that we arrive at at the very end of viewing the altarpiece.

Dr. Zucker: [13:51] This central figure of Anthony is surrounded by two panels that give us a sense of his biography, of the power of his spiritual experience.

Dr. Harris: [14:00] In this lush, verdant landscape, we see two figures. On the left, St. Anthony, who’s come to meet with St. Paul. Both men are hermits. Both have retreated from the world to focus on their spiritual lives.

Dr. Zucker: [14:18] The final panel on the right is perhaps the most inventive, certainly the most fantastical. Here we see the temptation of St. Anthony. We see St. Anthony accosted by demons.

Dr. Harris: [14:30] Anthony’s faith in God is being severely tested, probably very much like the patients in the hospital whose suffering was so terrible that they themselves lost faith in God. Here we see all sorts of demons with open mouths, torturing St. Anthony.

[14:52] On the bottom left, we see a very striking figure, who seems to be a hybrid human-animal who is covered with boils and scars and wounds, and even seems to have an amputated limb and this distended belly.

Dr. Zucker: [15:08] St. Anthony is holding onto his faith with all his might. You can see that in his right hand, which clutches at the rosary, this aid in prayer. There’s this wild invented creature that has the shell of a tortoise, the neck of a lizard, and the beak of a bird that is biting at his hand.

[15:27] Honestly, St. Anthony doesn’t seem to stand a chance. The demons have ganged up on him. They’re of every color, every texture, every shape. Some are feathered, some are winged, some are covered with skin. They hold weapons, they’re swinging clubs.

Dr. Harris: [15:41] Above, we see dark figures in silhouette who seem to be doing battle with angelic figures, and above it all, an image of God holding the scepter, pointing downward once again in this cloud, this halo of golden light.

[15:58] All of this rendered by an artist of immense talent, who could render the tiniest of details, but whose main achievement is this mystical vision, this painting that attempts in painterly form to express the inexpressible, this moment of the transformation of mankind from sin and evil in the control of the devil to redemption through God’s sacrifice.

[16:32] [music]

Object of devotion

If one were to compile a list of the most fantastically weird artistic productions of Renaissance Christianity, top honors might well go to Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece.

Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece (view in the Unterlinden Museum, Colmar), c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Constructed and painted between 1512 and 1516, the enormous moveable altarpiece, essentially a box of statues covered by folding wings, was created to serve as the central object of devotion in an Isenheim hospital built by the Brothers of St. Anthony. St. Anthony was a patron saint of those suffering from skin diseases. The pig who usually accompanies him in art is a reference to the use of pork fat to heal skin infections, but it also led to Anthony’s adoption as a patron saint of swineherds, totally unrelated to his reputation for healing and as the patron of basket-weavers, brush-makers, and gravediggers (he first lived as an anchorite, a type of religious hermit, in an empty sepulcher).

At the Isenheim hospital, the Antonine monks devoted themselves to the care of sick and dying peasants, many of them suffering from the effects of ergotism, a disease caused by consuming rye grain infected with fungus. Ergotism, popularly known as St. Anthony’s fire, caused hallucinations and skin infection, and attacked the central nervous system, eventually leading to death. It is perhaps not incidental to Grünewald’s vision for his altarpiece that the hallucinogen LSD was eventually isolated from the same strain of fungus.

Matthias Grünewald (painter), Nicolas of Hagenau (sculptor), Isenheim Altarpiece (fully open position), c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Sculpted altar

Sculpted wooden altars were popular in Germany at the time. At the heart of the altarpiece, Nicolas of Hagenau’s central carved and gilded ensemble consists of rather staid, solid, and unimaginative representations of three saints important to the Antonine order; a bearded and enthroned St. Anthony flanked by standing figures of St. Jerome and St. Augustine. Below, in the carved predella, usually covered by a painted panel, a carved Christ stands at the center of seated apostles, six to each side, grouped in separate groups of three. Hagenau’s interior ensemble is therefore symmetrical, rational, mathematical, and replete with numerical perfections—one, three, four, and twelve.

Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece (closed), c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Painted panels

Grünewald’s painted panels come from a different world; visions of hell on earth, in which the physical and psychological torments that afflicted Christ and a host of saints are rendered as visions wrought in dissonant psychedelic color, and played out by distorted figures—men, women, angels, and demons—lit by streaking strident light and placed in eerie other-worldly landscapes. The painted panels fold out to reveal three distinct ensembles. In its common, closed position the central panels close to depict a horrific, night-time Crucifixion.

Crucifixion (detail), left: the Virgin and the young St. John the Evangelist (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); middle: Christ on the cross (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: John the Baptist and a scroll that reads “he must increase, but I must decrease.” (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, view in the chapel of the Hospital of Saint Anthony, Isenheim, c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France)

The macabre and distorted Christ is splayed on the cross, his hands writhing in agony, his body marked with livid spots of pox. The Virgin swoons into the waiting arms of the young St. John the Evangelist while John the Baptist, on the other side (not commonly depicted at the Crucifixion), gestures towards the suffering body at the center and holds a scroll which reads “he must increase, but I must decrease.” The emphatic physical suffering was intended to be thaumaturgic (miracle performing), a point of identification for the denizens of the hospital. The flanking panels depict St. Sebastian, long known as a plague saint because of his body pocked by arrows, and St. Anthony Abbot.

Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece (second position) c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The second position emphasizes this promise of resurrection. Its panels depict the Annunciation, the Virgin and Child with a host of musical angels, and the Resurrection. The progression from left to right is a highlight reel of Christ’s life.

Crucifixion (detail), Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the predella panel is a Lamentation, the sprawling and horrifyingly punctured dead body of Christ is presented as an invitation to contemplate mortality and resurrection.

Virgin and child (detail), Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Idiosyncratic visions

All three scenes are, however, highly idiosyncratic and personal visions of Biblical exegesis; the musical angels, in their Gothic bandstand, are lit by an eerie orange-yellow light while the adjacent Madonna of Humility sits in a twilight landscape lit by flickering, fiery atmospheric clouds.

Resurrection panel, Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Resurrection panel is the strangest of these inner visions. Christ is wreathed in orange, red, and yellow body halos and rises like a streaking fireball, hovering over the sepulcher and the bodies of the sleeping soldiers, a combination of Transfiguration, Resurrection, and Ascension.

Far left and far right panels seen when altarpiece is fully open (here illustrated sided-by-side). Left: the Temptations of Saint Anthony (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Saint Anthony visits Saint Paul (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France)

Hybrid demons

Grünewald saves his most esoteric visions for the fully open position of the altar, in the two inner panels that flank the central sculptures. On the left, St. Anthony visits St. Paul (the first hermit of the desert) in the blasted-out wilderness—the two are about to be fed by the raven in the tree above, and Anthony will later be called upon to bury St. Paul. The meeting cured St. Anthony of the misperception that he was the first desert hermit, and was therefore a lesson in humility.

Temptations of Saint Anthony panel (detail), Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, c. 1512–16, oil and tempera on limewood panels, 376 x 668 cm (Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the final panel, Grünewald lets his imagination run riot in the depiction of St. Anthony’s temptations in the desert; sublime hybrid demons, like Daliesque dreams, torment Anthony’s waking and sleeping hours, bringing to life the saint’s torment and mirroring the physical and psychic suffering of the hospital patients.

Grünewald’s mastery of medieval monstrosity echoes and evokes Hieronymus Bosch and has inspired artists ever since. The entire altarpiece is a paean to human suffering and an essay on faith and the hope for heaven in the troubled years before the Reformation.