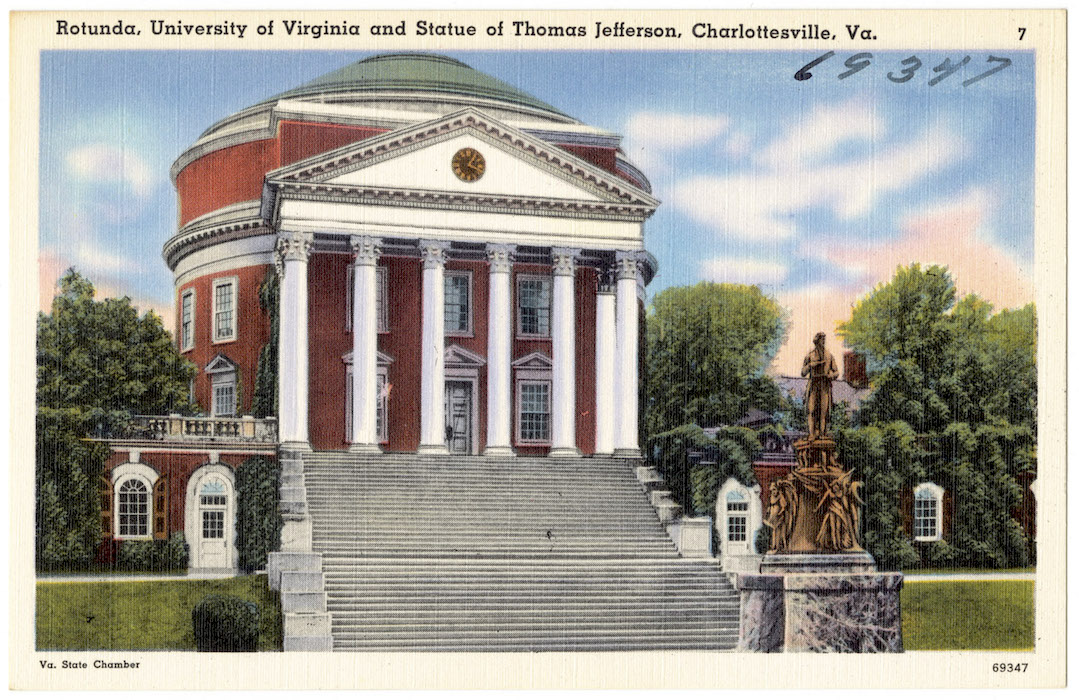

Rotunda, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia (photo: Brian Jeffery Beggerly, CC BY 2.0)

A joke with a kernel of truth

The College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia is the second oldest university in the United States and was founded in 1693 (only Harvard, founded in 1636, is older). There is a longstanding joke amongst graduates of this institution:

Question: Why did Thomas Jefferson found the University of Virginia?

Answer: His kids could not get into the College of William & Mary.

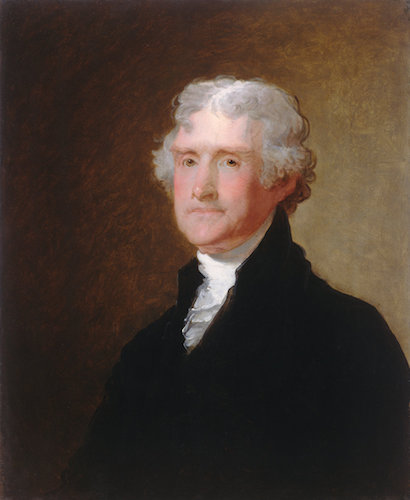

To be fair, there is some truth to this joke, and then again, there is some misdirection. Thomas Jefferson did, in fact, found the University of Virginia—an achievement of which he was so proud that it is mentioned on his tombstone (whereas he omitted the fact that he was the third president of the United States). But the other part of the joke—that his children could not have been admitted to his alma mater—is a bit misleading. Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles, died in 1782. During their ten years of marriage, she bore him six children, only two of whom lived to adulthood. Both of these were women, and as the College of William & Mary did not formally admit female students until 1918, it would have been impossible for Jefferson’s children (those who survived and were legitimate, at least) to enroll in the institution that had educated their father.

Wren building (West side), William and Mary College, 1695-1700 (photo: Smash the Iron Cage, CC BY-SA 4.0)

American universities have traditionally begun with a single building and then expanded over time. This was the case of the College of William & Mary; the so-called Wren Building (above) is the oldest surviving university building in the United States. Although originally called simply “The College” or “The Main Building,” it has subsequently come to be named after Sir Christopher Wren, the English baroque architect. In fact, Hugh Jones, the college’s first professor of mathematics wrote in 1722 that Wren himself was the architect: “the building is beautiful and commodious, being first modeled by Sir Christopher Wren…” However, architectural historians do not currently believe that the most accomplished architect in the English-speaking world at the end of the seventeenth century would have made time to design a building on the very fringes of the British Empire.

Sir Christopher Wren, Royal Hospital, Chelsea, 1692 (photo: stu smith, CC BY-ND 2.0)

A preference for the French (over the English)

Although it is unlikely that Wren designed this building at William and Mary College, there can be no doubt that whoever did was strongly influenced by Wren’s Royal Hospital at Chelsea (above). Both buildings have architectural elements that are indicative of late Renaissance and Baroque architecture in England. Both are horizontal in nature with a central pediment and cupola. Moreover, they share a similar fenestration (window) arrangement, and nearly identical dormer windows (windows that project from a sloping roof). For Thomas Jefferson, the Wren Building at the College of William & Mary was a prototype example of English architecture.

Thomas Jefferson and Charles-Louis Clérisseau, Virginia State Capitol, completed 1792 (photo: Mr.TinDC, CC BY-ND 2.0)

And if the political history of the United States tell us anything, it is that Thomas Jefferson did not much care for the English. This is but one of the reasons why his own architectural projects—notably his ancestral home at Monticello and the Virginia State Capitol (left)—were inspired not by English architectural antecedents, but instead by buildings from the classical past. Indeed, the Virginal State Capitol looks much like the Maison Carrée in Nîmes (France), an ancient Roman building Jefferson saw while serving as the American ambassador to France. His own home has a variety of classical (and neoclassical) architectural influences. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the neoclassical style was strongly linked with France—and Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican and strident Francophile, therefore approved.

University of Virginia: an “academical village”

At the conclusion of his political career, Jefferson turned his considerable energies towards two related enterprises: the founding of a university for the state of Virginia, and designing buildings for that institution. Jefferson very much believed in the crucial importance of education. Although an oft-repeated quotation—“An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.”—never seems to have come from his pen, it very much encapsulates Jefferson’s views on education. When he set in planning the University of Virginia—an institution founded in 1819 and began to instruct its first class in March 1825—he did so in a revolutionary way. Rather than begin as a single building and expand as needed, Jefferson envisioned—to use his phrase—an entire “academical village” where students and professor lived and learn side by side.

Jefferson designed the initial phase of the university on a symmetrical north-south axis. The longitudinal axes on the east and west sides contain pavilions for the professors, dormitories for the students, and expansive lawns. Indeed, the word “campus”—a word so commonly used to describe the grounds and buildings of a college or university—comes from the Latin word that means field. In this way, what Jefferson designed was one of the first true college campuses, complete with buildings and intentional exterior spaces.

The Rotunda (and the Pantheon)

Thomas Jefferson, Rotunda, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1817-26 (postcard c. 1930-45, Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0)

The crowing architectural achievement of the “academical village” at the University of Virginia can be seen at the north end of the campus. Called the Rotunda, it should look immediately familiar to anyone with even a passing knowledge of Western architecture, as Jefferson designed it as a half-sized version of the ancient Roman Pantheon (below). A religious building devoted to all the Roman gods, the Pantheon demonstrates the ways in which Roman architects could take a Classical Greek idea—note the Greek temple front—and combine it with elements that were so spectacularly new that it made the Pantheon architecturally unique for nearly two millennia. Indeed, that uniqueness derives from the innovative “dome on a drum” construction that is so neatly hidden—when viewed from its ideal angle—by the Greek temple front that Roman architects so admired. Moreover, this dome, which opens into a vast interior space crowned by a singular window (or oculus) was made possible through a particularly Roman invention: concrete.

The Pantheon, Rome, c. 125 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Yet Jefferson knew that his Rotunda was going to serve a different function than the building on which it was based. So, although these two buildings (The Pantheon in Rome and the Rotunda at the University of Virginia) look strikingly similar if you merely look at the architectural forms, they become quite different if one moves beyond initial appearance. Whereas the Pantheon is a religious building—a temple for all the Roman gods when it was created (and subsequently a Catholic church when it was consecrated in 609), Jefferson’s Rotunda has a strictly secular nature. As a member of the Enlightenment, Jefferson’s religious views leaned towards Deism, a belief system that generally acknowledged a Divine Maker, but rejected a belief in revelation. In fact, one of the reasons why Jefferson was keen on founding the University of Virginia was to provide his home state with a secular educational option to the religiously-oriented College of William & Mary. The materials were clearly different as well. While the expansive interior space of the Pantheon was made possible through the perfection of poured concrete, Jefferson used the wood and brick that was so indicative of mid-Atlantic architecture of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Two final differences involve the plans of the building on the ways in which light works. Whereas the Pantheon is essentially one enclosed space that is illuminated by only two sources—the oculus at the peak of the dome and the door at the building’s entrance—Jefferson’s Rotunda is a multistoried building that is illuminated by windows that circle the drum of the dome.

One might wonder why an architect in nineteenth-century America would model a library after an ancient Roman temple. But Neoclassical architecture surrounds us to this day (Neoclassical means “new classicism”—this is a style that developed in Europe at the end of the 18th century). Government buildings, colleges and universities, libraries, museums, and banks have all frequently used the architecture of the classical past as a way of giving the establishments they represent a sense of gravitas. In utilizing classical (ancient Greek and Roman) architectural forms for his library, Jefferson was expressing his admiration of the ideas set forth from the classical past: democracy, learning, and permanence. And, to make it more emphatic, the Rotunda was far removed from anything that could be considered British.

Influence

Thomas Jefferson’s resume is unmatched in the history of American politics. He was the third president of the United States (1801-09), the second vice president of the United States (1797-1801), and the first Secretary of State of the United States (1790-93). He served as the Minister to France (1785-89), a Delegate to the Congress of the Confederation (1783-84), as the governor of Virginia (1779-81), and Delegate to the Continental Congress (1775-1776). He also wrote the State of Virginia’s A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom (1777) and was the primary author of what many believe to be one of the most perfect political documents ever written, The Declaration of Independence (1776). And yet, had Jefferson been and written none of these things, he would still be remembered today as one of the most influential architects in the history of the United States. In many ways, the Rotunda is the cardinal architectural achievement on what Jefferson thought was one of his most profound accomplishments, the founding of the University of Virginia.

Additional resources:

Thomas Jefferson: The Architect of a Nation

Monticello and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville from UNESCO