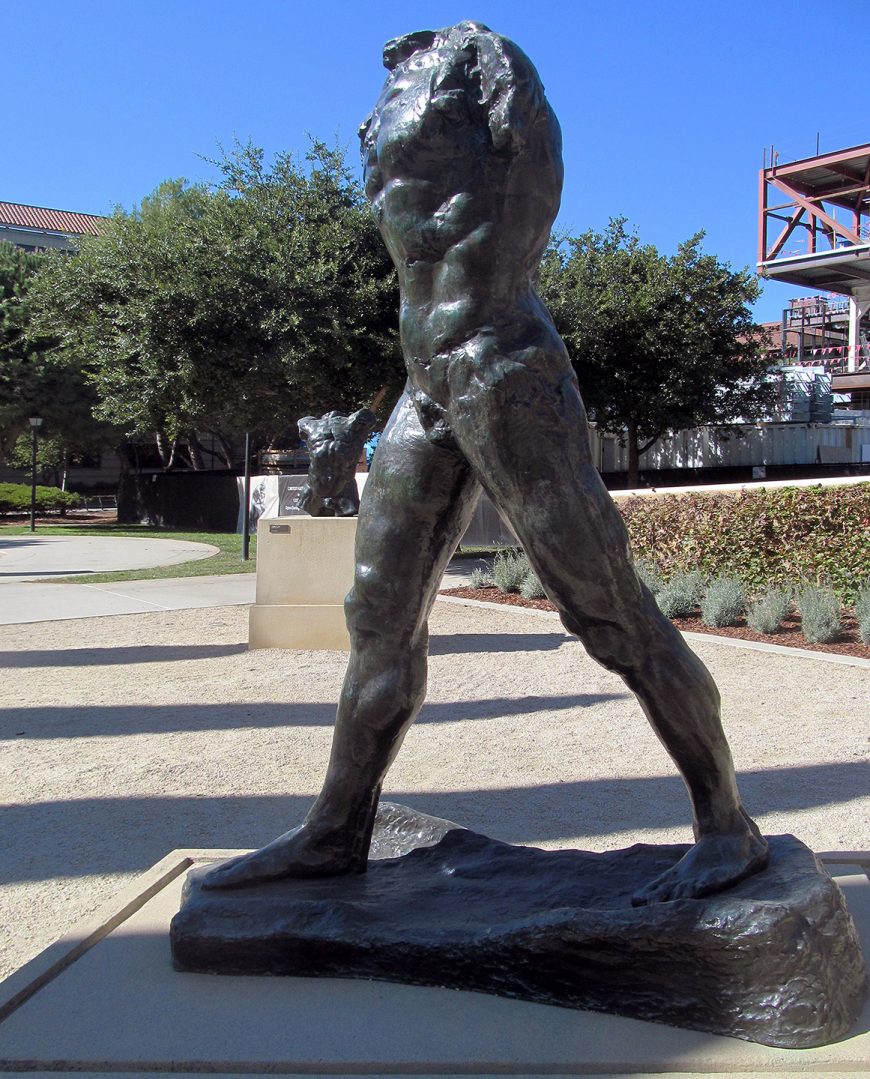

Auguste Rodin, The Walking Man, c. 1877, bronze (cast 7 of 12), 224 x 75 x 135 cm, Stanford University (photo: Rocor CC BY-NC 2)

Who decides when a work of art is finished? An initial reaction may have you saying that the answer is the artist, but what happens when the artist’s painting or sculpture goes against preconceived notions of what constitutes a “completed” work of art? Auguste Rodin, a French artist who worked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was more interested in rough, blemished representations of the human body than idealized forms. He painstakingly immersed himself in his projects, sometimes spending years in order to develop a work of art, regardless of the public’s response. His sculpture was often judged harshly by the public and by critics (sculpture was in some ways a more conservative tradition than was painting).

Reuse

Like a painter who reworked an old canvas, Rodin had a penchant for reusing old molds and reworking his earlier ideas. While this was not uncommon among artists, Rodin would continue to alter an existing form until it developed a new identity and a new narrative. Rodin transformed a major work, a bronze sculpture—over the course of two decades—and titled it, The Walking Man.

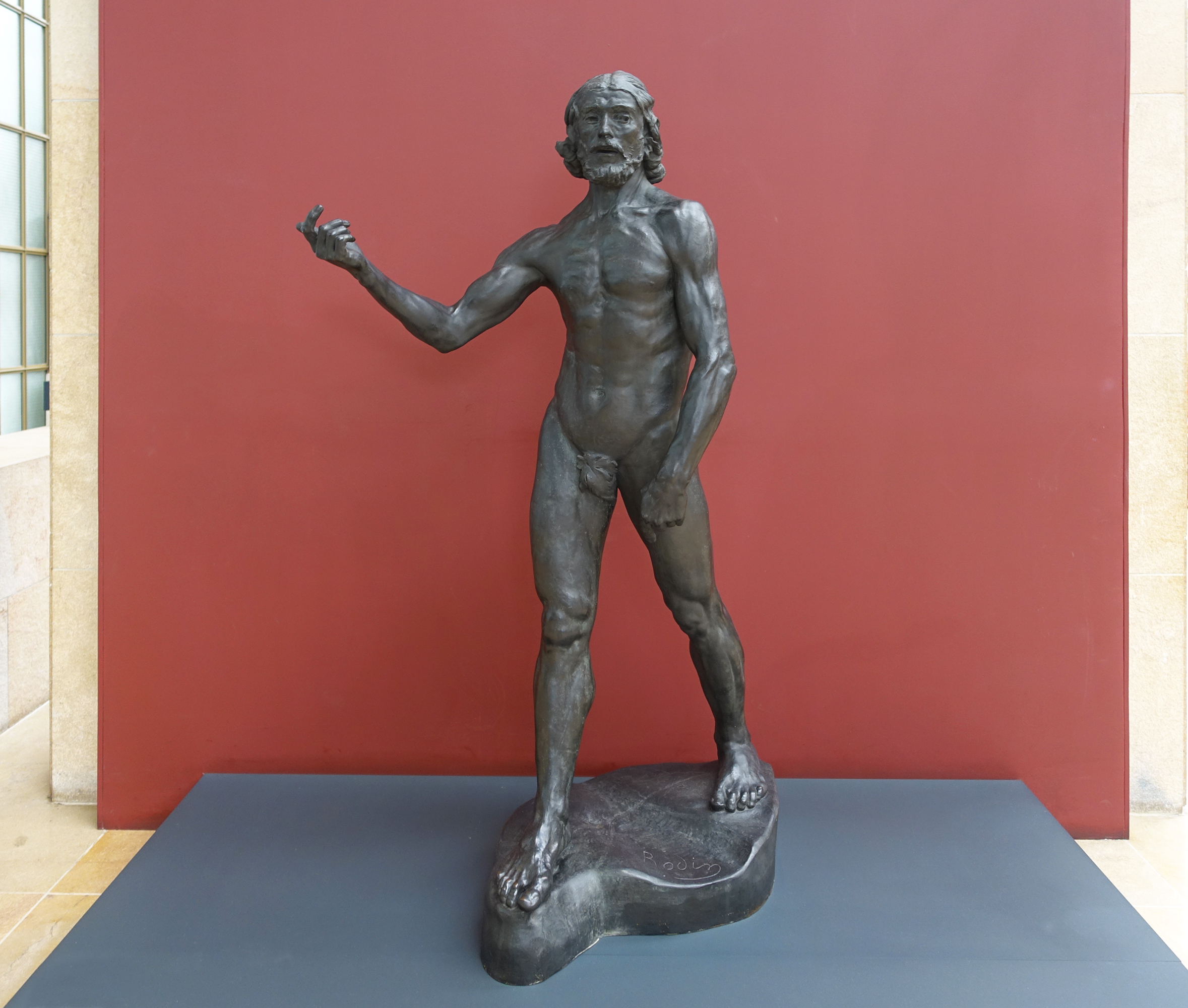

Auguste Rodin, Saint John the Baptist Preaching, 1878, bronze, 204 x 63 x 113 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

The Walking Man, started with his c. 1877 life-sized sculpture Saint John the Baptist Preaching (above), considered by many to be Rodin’s first life-sized masterpiece. The figure of Saint John is the embodiment of determination, with his head held high and his feet securely planted into the earthen bronze; his body balanced with the right arm extended as a counterweight to the contrapposto turn of his hips. Rodin was clearly interested in representing movement in this statue and continued to explore ways to perfect his “walking man.”

Auguste Rodin, The Walking Man, before 1900 (cast by Alexis Rudier before 1914), bronze with green patina, 85.1 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Power and movement

Rodin reused the widely-spread triangle-shaped stance from Saint John the Baptist Preaching and paired it with, what is thought to be, the torso mold from another earlier project. What resulted was a fragmented figure expressing power and movement. That Rodin was able to accomplish this without including a head and arms is remarkable and startling. The rough, fragmented body nevertheless achieves a solid stance and caused critics to complain that The Walking Man failed doubly; it could not possibly depict a man, and it was not walking.

This criticism missed the brilliant risk Rodin had taken. The male figure is posed in a wide stance, with the back foot turned to the side while the front weight-bearing foot is pointed straight ahead. The hips and torso are forward ready to take that much needed next step. The movement and motion is all right there in the arching torso, strong legs, and widely-spaced feet. Including additional appendages was unnecessary and would distract from the powerful combination of mass and movement.

Antoine-Louis Barye, Theseus and the Minotaur (second version), bronze, 50.5 x 34 x 20.3 cm (The Walters Art Museum)

Rodin sculpted a jagged, textured surface instead of the traditionally smooth, unblemished skin that was preferred in the classically-inspired statues of that time (see the Barye sculpture, right). This uneven “skin” enhances the curvature of the calf and abdominal muscles as they tense and twist in preparation for the implied next stride.

The rough surface texture creates a continuous line of movement for the viewer’s eyes to follow. Motion is constant as light and shadow play across the surface. Unlike a sculpture with a smooth surface, light that reflects off of the uneven surfaces highlight its imperfections. Divots become darker and high crests become brighter. As the viewer moves around the statue, the light and dark areas change, appearing to undulate like the swells of the ocean.

Auguste Rodin, The Walking Man (detail), before 1900 (cast by Alexis Rudier before 1914), bronze with green patina, 85.1 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Rodin may not have created an overtly twisting and contorting figure, but the impression and implication of movement is very much present. He conveys motion and strength in a figure that is fragmented and seemingly unfinished. Does a statue need to include arms or a head in order for it to be declared complete? Do all limbs need to be present to depict movement? Rodin’s answer is no.