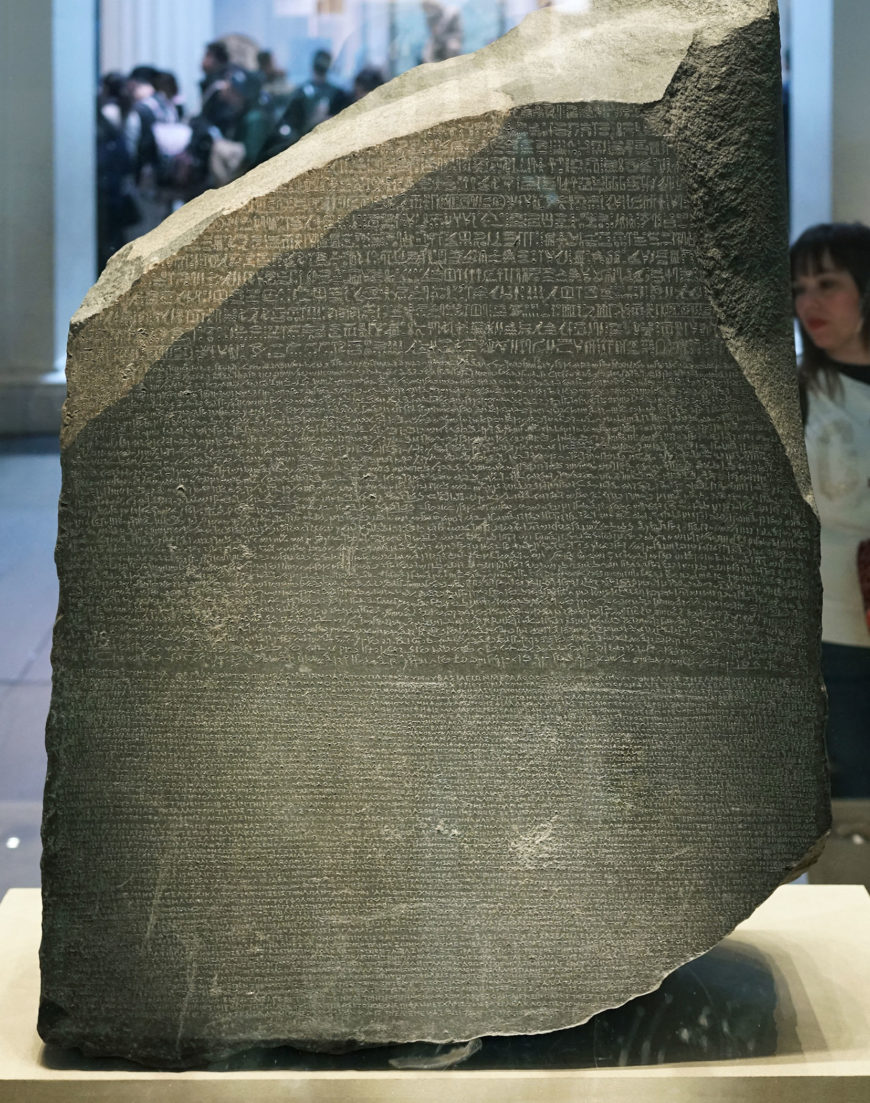

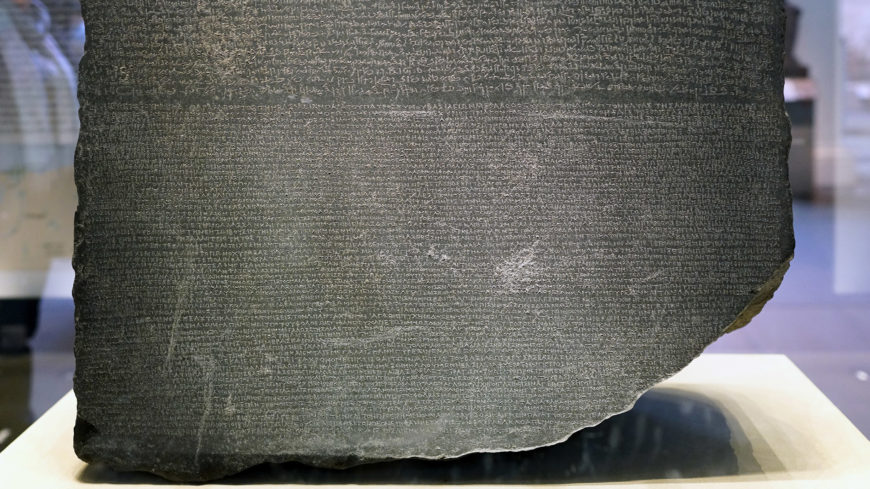

A conversation with Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker in front of the Rosetta Stone, Egypt, Ptolemaic Period, 196 B.C.E., granodiorite, 112.3 x 28.4 x 75.7 cm (The British Museum)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:03] The British Museum has just opened, but already there’s an enormous crowd circling the glass case that holds the Rosetta Stone.

[0:13] So, we’re not looking at this object in a museum because it’s a work of art.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:17] And it’s certainly not beautiful.

Dr. Zucker: [0:18] We value this ancient object largely for its modern history, as the key to deciphering the writing system that the Greeks called “sacred writing”: hieroglyphics.

Dr. Harris: [0:29] The Rosetta Stone is located in the middle of the gallery that contains ancient Egyptian art, and as we look around it’s so clear how important writing was to ancient Egyptian art. There’s almost no ancient Egyptian work of art that doesn’t also include writing.

Dr. Zucker: [0:47] Writing that we couldn’t read.

Dr. Harris: [0:48] Although we look back more than 5,000 years, the beginnings of ancient Egyptian culture.

Dr. Zucker: [0:53] This was made during the reign of Ptolemy V, in a period that we call the Ptolemaic period, a period that follows Alexander the Great’s conquest of ancient Egypt. Egypt at this point was ruled by a dynasty known as the Ptolemies.

Dr. Harris: [1:08] So we have Egypt being ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty, and that essentially means that Egypt is controlled by Greek rulers.

Dr. Zucker: [1:17] The Greek city of Alexandria had been founded in Egypt. Greek law had been imposed.

Dr. Harris: [1:22] The Ptolemies rule Egypt for almost three centuries until ancient Rome takes over in 30 B.C.E.

Dr. Zucker: [1:30] In order to understand the Rosetta Stone, it’s important to understand the political situation in Egypt at this moment. Ptolemy V, the reigning king, came to power when he was six years old.

Dr. Harris: [1:41] As you can imagine, there was a fight for power.

Dr. Zucker: [1:44] All of which is to say that this young king needed as many allies as he could get. He was looking to the ancient priestly class to help him assert his power and to stabilize the kingdom.

Dr. Harris: [1:55] During the reign of the Ptolemies, there’s a separation between the Greek-controlled government and the priestly class, the only ones who could read and write in hieroglyphics. Greek had become the official language of ancient Egypt.

Dr. Zucker: [2:11] By this late date, those Egyptians — other than the priests — who were literate would have written the Egyptian language in a different script, one known as Demotic. This stone reflects this historical moment in Egypt.

Dr. Harris: [2:25] At the very top, we’ve got hieroglyphics, the sacred writing of the priests; in the center, the Demotic script; and at the bottom, we have ancient Greek. It was the recognition that we had the same text in three different scripts that allowed scholars to recognize that the Rosetta Stone held the key to translating ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Dr. Zucker: [2:49] The stone is also a reflection of this historical moment. When the language of government was Greek, it’s this fracturing that allows us access to ancient Egyptian text, because the same decree is repeated in all three. In the 18th century, Europeans could read ancient Greek.

Dr. Harris: [3:08] This is a decree that speaks about the victory of Ptolemy V over some Egyptians who were rebelling against Greek rule. Because there is this tension within Egyptian culture at this moment between the priests and the Greek government, what we’re seeing in this decree is also a kind of compromise.

Dr. Zucker: [3:31] On the one hand, it’s the assertion of Ptolemy V’s power. But it also gives concessions to the priests.

Dr. Harris: [3:37] Before this, once a year the priests had to travel to the capital of Alexandria, which was Greek in essence, even though it was in ancient Egypt. This decree allowed them not to do that and to remain in Memphis, which was a historically great ancient Egyptian city.

Dr. Zucker: [3:54] It also gives the priests a tax cut. The third Memphis Decree, written on this stone in two different languages and three different scripts, is first and foremost a political compromise. What we’re seeing in the British Museum is only a fragment of what was originally a large stele, and one of numerous steles that were set up around Egypt with this same message.

Dr. Harris: [4:17] Let’s jump about 2,000 years to 1798, to the time of Napoleon and the British Empire. At this point, Egypt is in a strategic location for both the British and the French, who begin to vie for control of Egypt. Critically, Napoleon travels not only with his army but also with scholars, and when the stone is discovered, they quickly realize its historic importance.

Dr. Zucker: [4:47] Word of this discovery makes its way to Lord Elgin, a high-ranking British diplomat. Now, the British quickly defeat the French navy, but it’ll take the British a couple of years to oust the French land forces. When they do, the British look for the Rosetta Stone.

Dr. Harris: [5:01] But the French have hidden it. It is ultimately found. In the terms of a treaty ending these hostilities, the Rosetta Stone is mentioned as now being the property of the British.

Dr. Zucker: [5:12] It lands in the British Museum in 1802. Scholars almost immediately began to study the stone in an effort to read its hieroglyphs. Thomas Young made some headway, but it was really the French scholar, Champollion, that cracked the code.

Dr. Harris: [5:26] So for the last almost 200 years, thanks to a remarkable series of events through history, we’ve been able to read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and understand so much more about ancient Egyptian culture.

[5:39] [music]

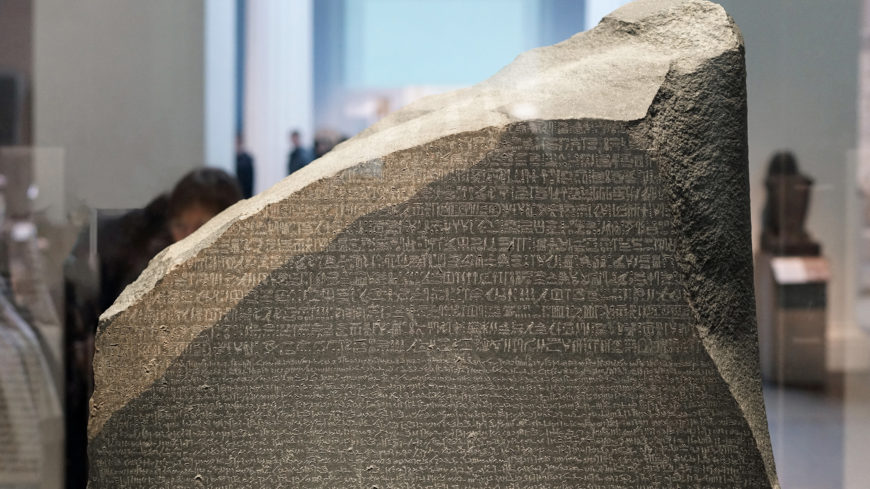

The Rosetta Stone, 196 B.C.E., Ptolemaic Period, 112.3 x 75.7 x 28.4 cm, Egypt (British Museum, London) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). The Rosetta Stone was discovered in Egypt, at Fort St Julien in el-Rashid, known as Rosetta.

The key to translating hieroglyphics

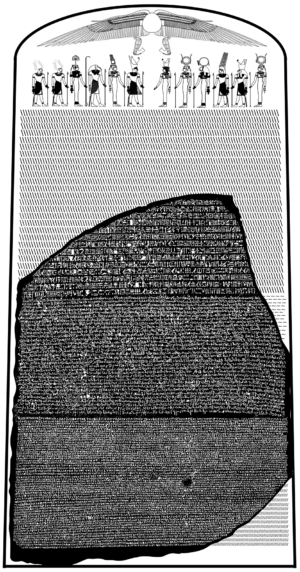

A reconstruction of the stela of which the Rosetta Stone was originally a part (A. Parrot, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most important objects in the British Museum as it holds the key to understanding Egyptian hieroglyphs—a script made up of small pictures that was used originally in ancient Egypt for religious texts. Hieroglyphic writing died out in Egypt in the fourth century C.E.. Over time the knowledge of how to read hieroglyphs was lost, until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 and its subsequent decipherment.

The Stone is a tablet of black rock called granodiorite. It is part of a larger inscribed stone that would have stood some 2 meters high. The top part of the stone has broken off at an angle—in line with a band of pink granite whose crystalline structure glints a little in the light. The back of the Rosetta stone is rough, where it has been hewn into shape, but the front face is smooth and crammed with text, inscribed in three different scripts. These form three distinct bands of writing.

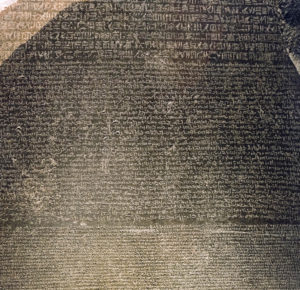

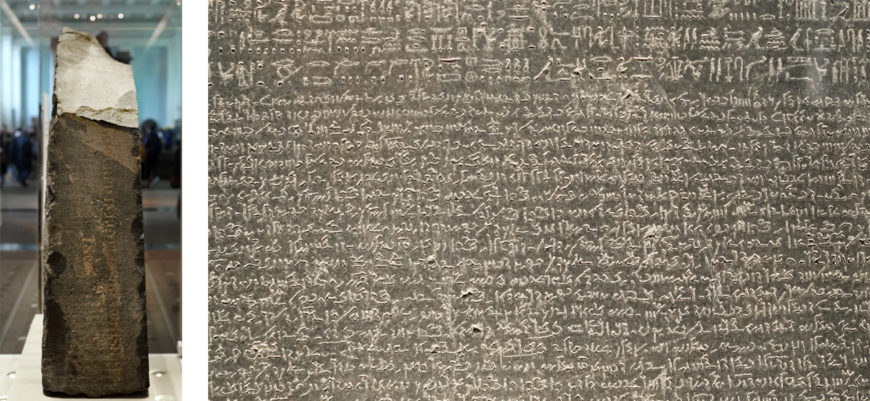

The Rosetta Stone (detail), 196 B.C.E., Ptolemaic Period, 112.3 x 75.7 x 28.4 cm, Egypt (British Museum, London) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Rosetta Stone, 196 B.C.E., Ptolemaic Period, 112.3 x 75.7 x 28.4 cm, Egypt (British Museum, London) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Part of grey and pink granodiorite stela bearing priestly decree concerning Ptolemy V in three blocks of text: Hieroglyphic (14 lines), Demotic (32 lines) and Greek (53 lines).

Three translations of the same decree

The inscriptions are three translations of the same decree, passed by a council of priests, that affirms the royal cult of the thirteen-year-old Ptolemy V on the first anniversary of his coronation. The decree is inscribed on the stone three times, in hieroglyphic (suitable for a priestly decree), demotic (the native script used for daily purposes), and Greek (the language of the administration). The importance of this to Egyptology is immense. In the early years of the nineteenth century, scholars were able to use the Greek inscription on this stone as the key to deciphering the others.

Opposition to the Ptolemies

In previous years the family of the Ptolemies had lost control of certain parts of the country. It had taken their armies some time to put down opposition in the Delta, and parts of southern Upper Egypt, particularly Thebes, were not yet back under the government’s control.

Before the Ptolemaic era (that is before about 332 B.C.E.), decrees in hieroglyphs such as this were usually set up by the king. It shows how much things had changed from Pharaonic times that the priests, the only people who had kept the knowledge of writing hieroglyphs, were now issuing such decrees. The list of good deeds done by the king for the temples hints at the way in which the support of the priests was ensured.

The end of hieroglyphics

Soon after the end of the fourth century C.E., when hieroglyphs had gone out of use, the knowledge of how to read and write them disappeared. In the early years of the nineteenth century, some 1400 years later, scholars were able to use the Greek inscription on this stone as the key to decipher them.

The discovery

Thomas Young, an English physicist, was the first to show that some of the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone wrote the sounds of a royal name, that of Ptolemy. The French scholar Jean-François Champollion then realized that hieroglyphs recorded the sound of the Egyptian language and laid the foundations of our knowledge of ancient Egyptian language and culture.

Soldiers in Napoleon’s army discovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799 while digging the foundations of an addition to a fort near the town of el-Rashid (Rosetta). On Napoleon’s defeat, the stone became the property of the British under the terms of the Treaty of Alexandria (1801) along with other antiquities that the French had found.

The Rosetta Stone has been exhibited in the British Museum since 1802, with only one break. Towards the end of the First World War, in 1917, when the Museum was concerned about heavy bombing in London, they moved it to safety along with other, portable, ‘important’ objects. The Rosetta Stone spent the next two years in a station on the Postal Tube Railway 50 feet below the ground at Holborn.

The Rosetta Stone (detail with Greek), 196 B.C.E., Ptolemaic Period, 112.3 x 75.7 x 28.4 cm, Egypt (British Museum, London) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Analyzing the Rosetta Stone

When the Rosetta Stone was discovered in 1799, the carved characters that covered its surface were quickly copied. Printer’s ink was applied to the Stone and white paper was laid over it. When the paper was removed, it revealed an exact copy of the text—but in reverse. Since then, many copies or “facsimiles” have been made using a variety of materials. Inevitably, the surface of the Stone accumulated many layers of material left over from these activities, despite attempts to remove any residue. Once on display, the grease from many thousands of human hands eager to touch the Stone added to the problem.

An opportunity for investigation and cleaning the Rosetta Stone arose when this famous object was made the centerpiece of the Cracking Codes exhibition at The British Museum in 1999. When work commenced to remove all but the original, ancient material, the stone was black with white lettering. As treatment progressed, the different substances uncovered were analyzed. Grease from human handling, a coating of carnauba wax from the early 1800s and printer’s ink from 1799 were cleaned away using cotton wool swabs and liniment of soap, white spirit, acetone and purified water. Finally, white paint in the text, applied in 1981, which had been left in place until now as a protective coating, was removed with cotton swabs and purified water. A small square at the bottom left corner of the face of the Stone was left untouched to show the darkened wax and the white infill.

Left: Detail of the right side of the Rosetta Stone; Right: Detail of the Rosetta Stone with Demotic script. The Rosetta Stone, 196 B.C.E., Ptolemaic Period, 112.3 x 75.7 x 28.4 cm, Egypt (British Museum, London) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

The Stone has a dark grey-pinkish tone with a pink streak running through it. Today you can see traces of a reddish brown in the text. This material was analyzed and found to be a clear mineral known as hydroxyapatite; the color may be due to iron traces. The mineral may have been applied deliberately, but there is no proof of this. This substance is not known by experts to have been used as a pigment, nor to have been used as a base for painting (a ground) in ancient Egypt.

Translation of the demotic text

[Year 9, Xandikos day 4], which is equivalent to the Egyptian month, second month of Peret, day 18, of the King “The Youth who has appeared as King in the place of his Father,” the Lord of the Uraei “Whose might is great, who has established Egypt, causing it to prosper, whose heart is beneficial before the gods…”

Read the rest of the Rosetta Stone translation here

© Trustees of the British Museum