Humankind’s origins and the beginnings of cultural expression may be traced to Africa. Recent discoveries in the southern tip of Africa provide remarkable evidence of the earliest stirrings of human creativity. Ocher plaques with engraved designs, made some 70,000 years ago, represent some of humankind’s earliest attempts at visual expression. Although much remains to be learned about Africa’s ancient civilizations through further archaeological research, such discoveries suggest tantalizing possibilities for rich insights into human as well as artistic evolution.

Rock paintings depicting domesticated animals provide artistic evidence of the existence of agricultural communities that developed in both the Sahara region and southern Africa by around 7000 B.C.E. As the Sahara began to dry up, sometime before 3000 B.C.E., these farming communities moved away. In the north, this led to the emergence of art-producing civilizations based along the Nile, the world’s longest river. Egypt, one of the world’s earliest nation-states, was unified as a kingdom by 3100 B.C.E. Further south along the Nile, one of the earliest of the Nubian kingdoms was centered at Kerma in present-day Sudan and dominated trade networks linking central Africa to Egypt for almost one thousand years beginning around 2500 B.C.E.

A corpus of sophisticated terracotta sculptures found over a broad geographic area in present-day Nigeria provides the earliest evidence of a settled community with ironworking technology south of the Sahara. The artistic creations of this culture are referred to as Nok, after the village where the first terracotta was discovered, and date to 500 B.C.E. to 200 C.E., a period of time coinciding with ancient Greek civilization. Although Nok terracottas continue to be unearthed, no organized excavations have been undertaken and little is known about the culture that produced these sculptures.

Seated Figure, terracotta, 13th century, Mali, Inland Niger Delta region, Djenné peoples, 25/4 x 29.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Terracotta heads, buried around 500 C.E., have also been found in north eastern South Africa. These important ancient artistic traditions are underrepresented in Western museums today, including the Metropolitan, due to restrictions regarding the export of archaeological materials.

Detail, Linguist Staff (Okyeame), 19th-early 20th century, Ghana, Akan peoples, Asante, gold foil, wood, nails, 156.5 x 14.6 x 5.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The first millennium C.E. witnessed the urbanization of a number of societies just south of the Sahara, in the broad stretch of savanna referred to as the western Sudan.

The strategic location of the Inland Niger Delta, lying in a fertile region between the Bani and Niger rivers, contributed to its emergence as an economic and cultural force in the area. Excavations there at the site of Jenne- jeno (“Old Jenne,” also known as Djenne-jeno) suggest the presence of an urban center populated as early as 2,000 years ago. The city continued to thrive for many centuries, becoming an important crossroads of a trans-Saharan trading network. Terracotta figures and fragments unearthed in the region reveal the rich sculptural heritage of a sophisticated urban culture (see the Seated Figure, above).

By the ninth century, trade across the Sahara had intensified, contributing to the rise of large state societies with diverse cultural traditions along trade routes in the western Sudan as well as introducing Islam into the region. Initially traversed by camel caravans beginning around the fifth century, established trans-Saharan trade routes ensured the lucrative exchange of gold mined in southern West Africa and salt from the Sahara, as well as other goods. Ghana, one of the earliest known kingdoms in this region, grew powerful by the eighth century through its monopoly over gold mines until its eventual demise in the twelfth century (see the Linguist Staff, left).

The present-day nation of Ghana takes its name from this ancient empire, although there is no historical or geographic connection.

A view of the Great Mosque of Djenné, designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988 along with the old town of Djenné, in the central region of Mali. (UN Photo/Marco Dormino, taken on March 25, 2015, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In the early thirteenth century, the kingdom of Mali ascended under the leadership of Sundiata Keita, who is still revered as a culture hero in the Mande-speaking world. At its height, this Islamic empire, which flourished until the seventeenth century, encompassed an area larger than western Europe and established Africa’s first university in Timbuktu. Under the Songhai empire of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, one of the largest in Africa, the cities of Timbuktu and Jenne (also known as Djenne) prospered as major centers of Islamic learning (image above).

Beyond the kingdoms of the western Sudan, other centers of cultural and artistic activity emerged elsewhere in western Africa. The art of metalworking flourished as early as the ninth century at a site called Igbo-Ukwu, in what is now southern Nigeria. Hundreds of intricate copper alloy castings discovered there provide artistic evidence of a sophisticated and technically accomplished culture.

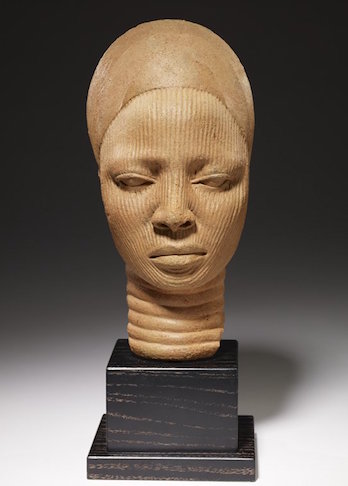

Shrine head, Yoruba, Nigeria, 12th-14th century, terracotta, 31.1 x 14.6 x 18.4 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Nearby to the west, the ancient site of Ife, considered the cradle of Yoruba civilization, emerged as a major metropolis by the eleventh century. Artists working for the royal court in Ife produced a large and diverse corpus of masterful work, including magnificent bronze and terracotta sculptures renowned for their portrait-like naturalism (image left). The rich artistic traditions of the Yoruba continue to thrive in the present day.

The neighboring kingdom of Benin, which traces its origins to Ife, established its present dynasty in the fourteenth century. Over the next 500 years, specialist artisans working for the Benin king created several thousand works, mostly made of luxury materials such as ivory and brass, that offer insights into life at the royal court (image below). Other state societies emerged in the eastern and southern parts of the continent.

Head of an Oba, Nigeria, Court of Benin, 16th century, brass, 23.5 x 21.9 c 22.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Bet Giyorgis Church, Lalibela, Ethiopia, c. 1220 (photo: Henrik Berger Jørgensen, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Aksum empire (also known as Axum), one of the earliest Christian states in Africa, flourished from the first century C.E. into the eleventh century, producing remarkable stone palaces and enormous granite funerary monoliths.

Christian faith inspired the artistic creations of later dynasties, including the extraordinary churches of Lalibela hewn from solid rock in the thirteenth century, and the illuminated manuscripts and other liturgical arts of the later Solomonic era.

Notable among the kingdoms that emerged in southern Africa is Mapungubwe in present-day Zimbabwe, a stratified society that arose in the eleventh century and grew wealthy through trade with Muslim merchants along the eastern African coast.

Just to the north are the remains of an ancient city known as Great Zimbabwe, considered one of the oldest and largest architectural structures in sub-Saharan Africa. This massive complex of stone buildings, spread over 1,800 acres, was constructed over 300 years beginning in the eleventh century.

Wall and tower, Great Enclosure, Great Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe, 14th century (photo: Ross Huggett, CC BY 2.0)

Lidded Saltcellar, 15th-16th century, Sierra Leone, Sapi-Portugese, ivory, 29.8 x 10.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the fifteenth century, the age of exploration ushered in a period of sustained engagement between Europe and Africa. The Portuguese, and later the Dutch and English, began trade with cities along the western coast of Africa around 1450. They returned from Africa with favorable accounts of powerful kingdoms as well as examples of African artistry commissioned from local sculptors. These exquisitely carved ivory artifacts, now known as the “Afro-Portuguese” ivories, were brought back from early visits to the continent and became part of the curiosity cabinets of the Renaissance nobles who sponsored exploration and trade.

Through trade, African artists were also introduced to new materials, forms, and ideas. Although historically glass and shell beads were made indigenously, trade with Europe in the sixteenth century introduced large quantities of manufactured glass beads that became widely used throughout Africa (see a later example here). European imports of copper and coral made these luxury materials more plentiful, and artists used them in greater quantities (as in the Head of an Oba, above). Artifacts of European manufacture, such as canes and chairs, served as prototypes for the development of new prestige items for regional leaders (as in the Linguist’s Staff, above). Along with goods imported from Europe, the travelers also brought with them their systems of belief, including Christianity. In some cases, such as in the central African kingdom of Kongo, Christianity was embraced and its iconography integrated into the artistic repertoire. In other parts of Africa, the foreign traders themselves were sometimes represented in artworks.

Crucifix, 16th-17th century, Democratic Republic of the Congo; Angola; Republic of the Congo, Kong Peoples, Kongo Kingdom, solid cast brass, 27.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”afrmet,”]

Additional resources:

African Rock Art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Inland Niger Delta on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Igbo-Ukwu on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Ife Terracottas (1000–1400 A.D.)

Origins and Empire: The Benin, Owo, and Ijebu Kingdoms

Mapungubwe (ca. 1050–1270) on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History