Sultan Muhammad (attributed), The Court of Kayumars (Safavid: Tabiz, Iran), c. 1524–1525, from the Shah Tahmasp Shahnameh, c. 1524–35, opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, 45 x 30 cm (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto) speaker: Dr. Michael Chagnon, Curator, Aga Khan Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

Sultan Muhammad (attributed), The Court of Kayumars (Safavid: Tabiz, Iran), c. 1524–1525, from the Shah Tahmasp Shahnameh, c. 1524–35, opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, 45 x 30 cm (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto) speakers: Dr. Filiz Çakir Phillip, Curator, Aga Khan Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

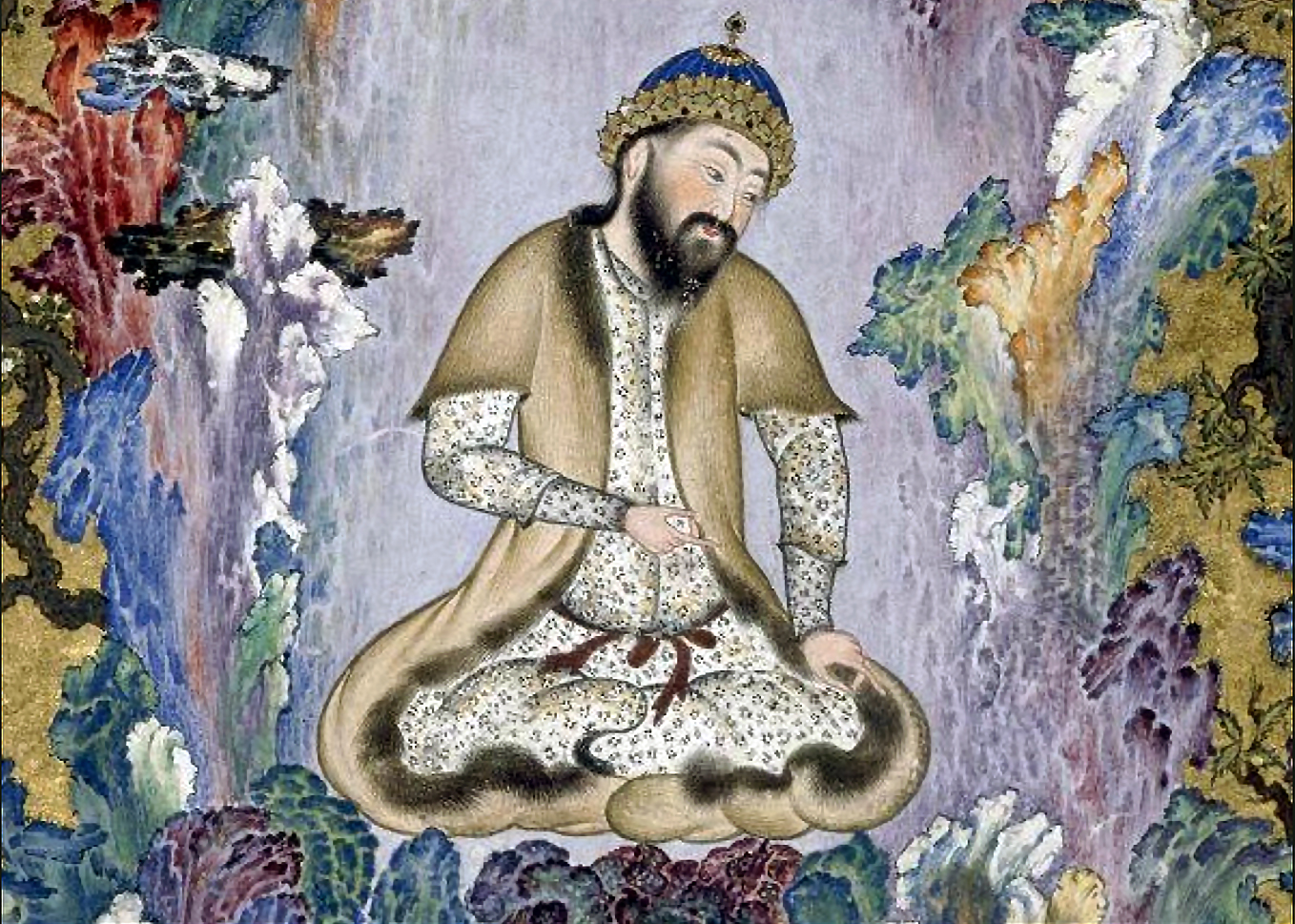

Whole page left, and detail, right: Sultan Muhammad, The Court of Gayumars, c.1522, 47 x 32 cm, opaque watercolor, ink, gold, silver on paper, folio 20v, Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp I (Safavid), Tabriz, Iran (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto)

The Shahnama

This sumptuous page, The Court of Gayumars (also spelled Kayumars— see top of page, details below and large image here), comes from an illuminated manuscript of the Shahnama (Book of Kings)—an epic poem describing the history of kingship in Persia (what is now Iran). Because of its blending of painting styles from both Tabriz and Herat (see map below), its luminous pigments, fine detail, and complex imagery, this copy of the Shahnama stands out in the history of the artistic production in Central Asia.

The Shahnama was written by Abu al-Qāsim Ferdowsi around the year 1000 and is a masterful example of Persian poetry. The epic chronicles kings and heroes who pre-date the introduction of Islam to Persia as well as the human experiences of love, suffering, and death. The epic has been copied countless times—often with elaborate illustrations (see another example here).

Safavid patronage

This particular manuscript of the Shahnama was begun during the first years of the 16th century for the first Safavid dynastic ruler, Shah Ismail I, but was completed under the direction of his son, Shah Tahmasp I in the northern Persian city of Tabriz (see map below). The Safavid dynastic rulers claimed to descend from Sufi shaikhs—mystical leaders from Ardabīl, in northwestern Iran. The name “Safavid” stems from one particular ancestral Sufi, named Shaykh Safi al-Din (literally translated as “purity of the religion”). Over a two-hundred-year span starting in 1501, the Safavids controlled large parts of what is today Iran and Azerbaijan (see map below). The Safavids actively commissioned the building of public architectural complexes such as mosques (image below), and they were patrons of the arts of the book. In fact, manuscript illumination was central to Safavid royal patronage of the arts.

The Imam Mosque (formerly Masjed-e Shah) was built for a later Safavid ruler during the 17th century, Isfahan, Iran. photo: Ladsgroup, GNU Free Documentation License

Depicting figures

It is often assumed that images that include human and animal figures, as seen in the detail below, are forbidden in Islam. Recent scholarship, however, highlights that throughout the history of Islam, there have been periods in which iconoclastic tendencies waxed and waned.1 That is to say, at specific moments and places, the representation of human or animal figures was tolerated to varying degrees.

Detail, Sultan Muhammad, The Court of Gayumars, c. 1522, 47 x 32 cm, opaque watercolor, ink, gold, silver on paper, folio 20v, Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp I (Safavid), Tabriz, Iran (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto)

There is a long figural tradition in Persia—even after the introduction of Islam—that is perhaps most evident in book illustration. It is also important to note that, unlike the neighboring Ottoman Empire to the west who were Sunni and in some ways more orthodox, the Safavids subscribed to the Shi’i sect of Islam.

Two centers of culture

Although it is widely recognized that the conventions of what is sometimes termed “classical”2 Persianate painting had become established by the fourteenth century, it is in the reign of Shah Tahmasp I that we see the most dramatic advancements in illumination and the arts of the book more generally.3 His patronage of this specific art form is in part due to his own painting studies in Herat (in the western region of present-day Afghanistan) and Tabriz (in the northwestern region of present-day Iran), under Bihzad and Sultan Muhammad, respectively.4 Both cities were major centers for the production of manuscript illuminations. While the entire manuscript of the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp I consists of approximately 759 illustrated folios and 258 miniatures all produced over the span of several years,5 this particular miniature is attributed to the workshop of Sultan Muhammad, according to Dust Muhammad, an artist and historian from this period.6 In 1568, this lavish Shahnameh was given as a gift by Shah Tahmasp I to the Ottoman Sultan, Selim II.7

Nasta’liq (detail), Sultan Muhammad, The Court of Gayumars, c. 1522, 47 x 32 cm, opaque watercolor, ink, gold, silver on paper, folio 20v, Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp I (Safavid), Tabriz, Iran (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto)

King of the world

There are several interpretive issues to keep in mind when analyzing Persianate paintings. As with many of the workshops of early modern West Asia, producing a page such as the Court of Gayumars often entailed the contributions of many artists. It is also important to remember that a miniature painting from an illuminated manuscript should not be thought of in isolation. The individual pages that we today find in museums, libraries, and private collections must be understood as but one sheet of a larger book—with its own history, conditions of production, and dispersement. To make matters even more complex, the relationship of text to image is rarely straightforward in Persianate manuscripts. Text and image, within these illuminations, do not always mirror each other.8 Nevertheless, the framed calligraphic nasta’liq (hanging)—the Persian text at the top and bottom of the frame (image above) can be roughly translated as follows:

When the sun reached the lamb constellation,9 when the world became glorious,

When the sun shined from the lamb constellation to rejuvenate the living beings entirely,

It was then when Gayumars became the King of the World.

He first built his residence in the mountains.

His prosperity and his palace rose from the mountains, and he and his people wore leopard pelts.

Cultivation began from him, and the garments and food were ample and fresh.10

King Gayumars (detail), Sultan Muhammad, The Court of Gayumars, c. 1522, 47 x 32 cm, opaque watercolor, ink, gold, silver on paper, folio 20v, Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp I (Safavid), Tabriz, Iran (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto).

Dense with detail

In this folio (page), we can see some parallels between the content of the calligraphic text and the painting itself. Seated in a cross-legged position, as if levitating within this richly vegetal and mountainous landscape, King Gayumars rises above his courtiers, who are gathered around at the base of the painting. According to legend, King Gayumars was the first king of Persia, and he ruled at a time when people clothed themselves exclusively in leopard pelts, as both the text and the represented subjects’ speckled garments indicate.

King Gayumars, Siyamak, and Hushang (detail), Sultan Muhammad, The Court of Gayumars, c. 1522, 47 x 32 cm, opaque watercolor, ink, gold, silver on paper, folio 20v, Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp I (Safavid), Tabriz, Iran (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto)

Perched on cliffs beside the King are his son, Siyamak (left, standing), and grandson Hushang (right, seated).11 Onlookers can be seen to surreptitiously peer out from the scraggly, blossoming branches onto King Gayumars from the upper left and right. The miniature’s spatial composition is organized on a vertical axis with the mountain behind the king in the distance, and the garden below in the foreground. Nevertheless, there are multiple points of perspective, and perhaps even multiple moments in time—rendering a scene dense with details meant to absorb and enchant the viewer.

Sutra Box with Dragons amid Clouds, c. 1403-24 (Yongle period, Ming dynasty), 14 x 12.7 x 40.6 cm, red lacquer with incised decoration inlaid with gold; damascened brass lock and key (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

One might see stylistic similarities between the swirling blue-gray clouds floating overhead with pictorial representations in Chinese art (image above); this is no coincidence. Persianate artists under the Safavids regularly incorporated visual motifs and techniques derived from Chinese sources.12 While the intense pigments of the rocky terrain seem to fade into the lush and verdant animal-laden garden below, a gold sky canopies the scene from above. This piece—in all its density color, detail, and sheer exuberance—is a testament to the longstanding cultural reverence for Ferdowsi’s epic tale and the unparalleled craftsmanship of both Sultan Muhammad and Shah Tahmasp’s workshops.

Notes

1. See Christiane Gruber, “Between Logos (Kalima) and Light (Nūr): Representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Painting,” Muqarnas 16 (2009), pp. 229-260; Finbarr B. Flood, “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum,” The Art Bulletin 84, 4 (December 2002), pp. 641-659; Christiane Gruber, “The Koran Does Not Forbid Images of the Prophet,” Newsweek (January 9, 2015).

2. For a helpful analysis of the historiographic ascription of the term ‘classical’ to Persian painting and the cultural hierarchy that was established largely by scholar-collectors in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, see Christiane Gruber, “Questioning the ‘Classical’ in Persian Painting: Models and Problems of Definition,” in the Journal of Art Historiography 6 (June 2012), pp. 1-25.

3. David J. Roxburgh, “Micrographia: Toward a Visual Logic of Persianate Painting,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 43 (Spring 2003), pp. 12-30.

4. Sheila Canby affirms Stuart Cary Welch’s estimate that it took Sultan Muhammad and his workshop three years to complete the Court of Gayumars illustration. Sheila Canby, The Golden Age of Persian Art, 1501-1722 (New York: Abrams, 2000), p. 51.

5. David J. Roxburgh, “On the Brink of Tragedy: The Court of Gayumars from Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama (‘Book of Kings’), Sultan Muhammad,” in Christopher Dell, ed., What Makes a Masterpiece: Artists, Writers and Curators on the World’s Greatest Works of Art (London; New York: Thames & Hudson, 2010), pp. 182-185; 182. The text was subsequently possessed by Baron Edmund de Rothschild and then sold to Arthur A. Houghton Jr, who in turn sold pages of the book individually.

6. Roxburgh, “Micrographia: Toward a Visual Logic of Persianate Painting,” p. 19. “In the Persianate painting, however, image follows after word in a linear sequence; the text introduces and follows after the image, but it is not actually read when the image is being viewed…In the Persian book the act of seeing is initiated by a process of remembering the narrative just told. Moreover, that text does not prepare the viewer for what will be seen in the painting.”

7. This expression denotes the beginning of spring.

8. I am grateful to Dr. Alireza Fatemi for generously providing this translation.

9. Roxburgh, “On the Brink of Tragedy,” p. 182.

Additional resources:

The Court of Gayumars at the Aga Khan Museum

Large image here (click for full-size)

Biography of the poet Abu al-Qāsim Ferdowsi, Encyclopaedia Iranica

The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”AgaKhanKayumars,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re standing in the galleries in the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, looking at one of the most famous, if not the most celebrated, Persian miniature. It is absolutely drop-dead stunning. This is a single folio, that is, a single page from a much larger book.

Dr. Michael Chagnon: [0:24] The “Shahnameh” was composed around the year 1000-1010. There were many, many manuscripts of the “Shahnameh.” This particular manuscript was produced with 258 illustrations around the year 1525-1535, a good 500 years after the composition of the text.

Dr. Zucker: [0:42] “Shahnameh” means the “Book of Kings,” and it is literally a mytho-history of the rulers of ancient Persia.

Dr. Chagnon: [0:49] The “Shahnameh” covers the reign of 50 kings. Frequently scholars talk about the text as having three sections: the first being a mythical section, the second being a heroic section, and the third being a historical section.

Dr. Zucker: [1:01] This volume would have been fabulously expensive to produce. It took decades.

Dr. Chagnon: [1:06] Entire departments or libraries of a king’s court would have been funded and mobilized, with teams of workers. Artists with different specialties, from gilding to painting and drawing, to using lapis, to creating a binding. Whole teams of artists brought together over many, many years to create a single manuscript.

[1:24] This particular manuscript is large. It’s lavishly illustrated. There’s a lot of gold and really high-quality pigments used. As you can see, you have the absolute height of artistry and draftsmanship coming together to create an incredibly gorgeous scene.

Dr. Zucker: [1:39] The longer I look, the more I see. There are the three principal figures, but then there are an almost uncountable number of subsidiary figures, some that are so subtle that they are almost impossible to recognize.

Dr. Chagnon: [1:52] You also have animals. You have embedded figures in the stones themselves in a sort of playful way to engage your viewing of this. These pictures were meant to be lovingly contemplated. They were meant to draw you in.

[2:06] Here we see the principal figure, Kayumars, the first king in the Persian tradition. He’s the one who brings civilization to the world. You see here a coming together of all different kinds of people who have just learned how to live in a civilized, harmonious way. Even the animals are seated side by side in absolute harmony.

Dr. Zucker: [2:24] The king is seated at the mountaintop. Below him you can see a waterfall, that I’m assuming was once bright silver, spilling down into this lush landscape that’s filled with vegetation. It’s filled with animals, and it is like a paradise.

Dr. Chagnon: [2:36] That’s right. It’s a paradise, and it’s a paradise on the brink of being lost. This is one of the great poignancies of this painting. We believe that the figure that Kayumars is signaling toward is his son, who’s about to be killed by the armies of the son of the Devil. We see this moment of coming together of humanity, of peace between peoples.

[3:01] But with the gesture of the king toward his son, who’s about to be lost, we have the foretelling of imminent doom. It’s a piece that hovers on the precipice of great drama.

Dr. Zucker: [3:11] The verdant landscape is so rich. It’s so fruitful that it literally spills out of the frame of the image onto the page itself. And that page is not plain but speckled with this wonderful, playful application of gold.

Dr. Chagnon: [3:23] With this mobilization of great artistic genius behind this piece, we have the gold-speckled borders as well as this beautifully executed landscape, not just verdant greenery but also multicolor rocks that spill out from beyond the inner margins. In doing that, it brings you into this world. And so we have a real sense of a play with depth.

[3:45] We’re not just looking at a flat series of elegantly applied colors. We’re actually looking into a world.

Dr. Zucker: [3:52] When I look at the clouds against that gold background or the way some of those rock formations are delineated, I can’t help but think about the great history of Chinese painting.

Dr. Chagnon: [4:01] Through many centuries preceding the creation of this manuscript, there was really intensive interaction between East Asia and the Iranian world. That was most prominently affected by the establishment of the Mongol Empire, that stretched across the entire expanse of Asia, essentially.

[4:19] With that, you had an exchange of ideas, an exchange of visual forms, an exchange of techniques that get really digested into the Persian painting repertoire.

Dr. Zucker: [4:28] It’s important to note that the script itself is its own art form, and one that is prominent in art throughout the Islamic world.

Dr. Chagnon: [4:34] That’s right. Calligraphy is really the highest form of art, traditionally, in the Islamic world, and that’s because the word is itself central to Islam.

Dr. Zucker: [4:43] But this is not religious text, this is secular text. This is about the history of Persia, and it’s important to Iran as an expression of Iran’s historical identity.

Dr. Chagnon: [4:54] That’s right. The “Shahnameh” was composed at a time that historians call the Iranian Revival. It’s at a moment after the Islamization of the Iranian world, when literature and language in Persian was being reinvigorated.

[5:09] This particular text is actually a combination of a lot of different mini-epics that were stitched together and versified by the poet Ferdowsi as an expression of this new revived consciousness of Iranian-ness at the turn of the 11th century.

Dr. Zucker: [5:25] Then half a millennium later, there’s an additional revival when the Safavid[s] reestablished the unity of Persia.

Dr. Chagnon: [5:32] That’s right. In 1501, you have the establishment of the Safavid dynasty. Within a decade or two, you have the quick consolidation of all of the former territories of Iran, which had previously been quite atomized.

[5:48] With this reunification, you have the dominance, once again, of Persian literary forms. Also, the Safavids are quite well known for establishing Shiism as the state religion of Iran.

[6:00] It’s an incredibly historical manuscript. The text, of course, is central to Iranian identity as the book of Iranian kingship, but also because this is one of the very few, if not the only, painting in Persian tradition that is actually recorded and spoken about by [a] contemporary historian.

[6:18] A couple of decades after this was produced, in the 1540s, a writer, Dust Muhammad, composed a preface to an album. In that, he speaks about the painter Sultan Muhammad, and he speaks about this painting in particular, of Kayumars, with all of the figures dressed in leopard skins.

[6:34] And so it’s a really important piece. We don’t have a lot of paintings in the Persian tradition that are actually written about and historically recorded. This a very, very important individual piece, and it’s a real treasure to have here in Toronto.

[6:47] [music]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, standing in front of a case that holds one of the most celebrated Iranian paintings. But this is not a painting that was meant to be seen in isolation. This was originally a folio, a page in a very large book.

Dr. Filiz Çakir Phillip: [0:19] It is from the manuscript of “Shahnameh,” “Book of Kings,” which was dedicated for Shah Tahmasp, who was the second ruler of [the] Safavid dynasty in Iran, in early 16th century.

Dr. Zucker: [0:31] That dynasty was especially important because it had reunited Iran, which had been fragmented immediately before. What’s being represented here is this first kingdom that was so harmonious that we might even look at it as a kind of paradise.

Dr. Phillip: [0:46] We have different physiognomy. We have Central Asian-looking faces, we have brown faces. It was important for Sultan Muhammad to depict many variety as possible who are included in the court of Kayumars.

Dr. Zucker: [1:00] What we’re looking at is the first kingship, one that is described as being a place of harmony. So much so that even the wild animals are tame. If you look closely, you can see a man holding a lion.

Dr. Phillip: [1:14] This is the depiction of harmony, but on the other hand, maybe we should go back and ask ourselves, who was Kayumars for the Iranian history.

[1:23] “Shahnameh” is a book which was written by Ferdowsi. It was important for him to document after the Arabic invasion, with the fears we are losing our tradition and we are going to be introduced into another culture, and then how we can protect and support our own culture.

[1:41] So this was the main idea of Ferdowsi. Kayumars is in that regard is very important because Kayumars is [an] immortal mythological king, but he decides to give up his immortality. He has the same equal quality and importance when we compare with Adam.

Dr. Zucker: [1:59] The highest figure is Kayumars. He is at the top of a triangle of figures and seems to almost float above the landscape. The composition here is so complicated, and there are so many figures that are within it, but our eye always goes back to the king.

Dr. Phillip: [2:13] He is sitting on the throne, but behind him is the cave. So this is the beginning of human civilization. When I look at Kayumars and this peaceful, harmonious painting, I see his dedication for humans. So he has chosen and then he dedicates himself for human society.

[2:31] Then looking at in a painting, which is a part of a manuscript dedicated to educate the next-generation rulers, how to behave, how to become a good ruler, and celebrate justice. It is a really fantastic decision that we should be grateful for that.

[2:50] We have contemporaneous sources which explain Sultan Muhammad was working on this magnificent painting more than three years. I think we should celebrate it and take time and look at in depth.

[3:03] [music]