The Baths of Caracalla, Rome, view from the south-west of the caldarium (hot baths). Construction on the Baths of Caracalla (known in the ancient world as the Thermae Antoninianae), may have begun under Emperor Septimius Severus. However, most of the work was completed under his son, the emperor Lucius Septimius Bassianus (known as Caracalla) between 212–17 C.E. Due to the size and lavish decorations of the complex, it was not fully completed until 235 C.E. (photo: Ethan Doyle White, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The remains of broken vaults, towering arches, and expansive walls soar into the air, some as high as 130 feet. Rooms now lie open to the sky above while colorful mosaics still remain underfoot. Although the Baths of Caracalla retain only a fraction of their former opulence, the sprawling complex, the second largest ancient baths in Rome, is still impressive today.

The coffers in the barrel vault of the Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine (c. 306–12) likely resembled the ones at the Baths of Caracalla.

Expansive public bathing complexes like the Baths of Caracalla were made possible thanks to the extensive aqueducts that the Romans constructed to supply water to cities like Rome. A new aqueduct, the Aqua Antoniniana (a branch of the earlier Aqua Marcia), was constructed to transport water to the baths. The Via Nova (New Road), was also created to provide access to the structure. This new construction, as well as the structure itself and the decorations within it, were paid for from imperial funds.

The structures were comprised of brick-faced concrete, which was once hidden under marble, mosaics, and decorative stucco work, topped with enormous vaults covered with polychrome glass mosaic. These vaults contained coffers that helped reduce their weight. Today, much of the decoration is gone, leaving the brick-faced concrete exposed.

The importance of bathing

Bathing was an essential part of ancient Roman urban life and spending the afternoon in the baths was a normal occurrence. The ancient Romans believed that daily exercise and bathing were necessary components to maintaining a healthy lifestyle, which is not so different from us today. The baths were also places to socialize and even conduct business.

The baths were a place where all levels of Roman society could mix. While some elite ancient Romans did have small baths in their homes and villas, even they would sometimes frequent public baths. Because the baths were free and open to the public, the non-elite peoples of Rome could also enjoy these lavish facilities.

Marcus Agrippa, the best friend and son-in-law of Augustus (the first emperor of Rome), is credited with building the city’s first permanent public bathing complex in the Campus Martius in 25 B.C.E. Over the next three centuries, various emperors of Rome constructed their own bath complexes. This not only helped serve the growing population of Rome, but also allowed emperors to leave a lasting legacy. Baths were not only found in the capital city, but in cities across the empire. However, even though imperial bath complexes (thermae) had existed for as long as the empire had, Caracalla’s baths dwarfed all the others.

More than just baths

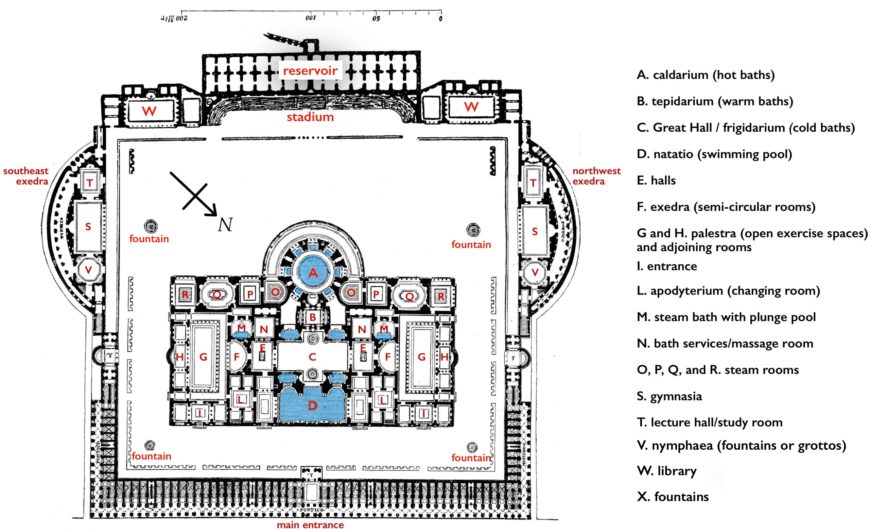

Though today we label the structure as “baths,” the bathing rooms make up only one portion of these large complexes. Located near the Aventine Hill in Rome, the complex sprawls across an area of approximately 27 acres. It was surrounded by a large perimeter wall, and public shops lined the entire northeast wall as well as portions of the northwest and southeast walls.

The main entrance into the complex was in the center of the northwest wall. Upon entering, visitors would be confronted with extensive, manicured gardens beyond which rose the walls of the bath building. The gardens surrounded the entire bath building within the precinct walls and included plants, walking paths, and fountains.

Part of the southeast and northwest precinct walls were designed as large exedrae (the semicircular areas) containing additional rooms such as gymnasia, lecture halls, and nymphaea (monumental fountains or grottos).

Floor covered in opus sectile, Baths of Caracalla, Rome (photo: Mikael Korhonen, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Columns, Santa Maria Trastevere, Rome (photo: Dave Simpson, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Other rooms in the precinct walls include two large libraries, one for Greek texts and one for Latin. Only one of the libraries remains today, heavily damaged but still recognizable. Within it are 32 large niches which once held wooden shelves on which papyrus scrolls had rested. A monumental niche topped with a half-dome in the center of the wall opposite the entrance originally held a sculpture. The floor was covered in opus sectile (cut stonework) made up of expensive marbles. Masonry benches running the interior perimeter of the room provided seating. Many of the marble columns in the library survived for centuries but were removed in the 12th century and reused in the Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome.

On the far side of each library were two large staircases which linked the southwestern side of the complex with the neighboring Aventine Hill. Between the two libraries was a stadium for athletic events which also functioned as a running track, surrounded on three sides with a seating area. Behind that was a large, two-story reservoir connected to the Aqua Antoniniana. Water was also held in various cisterns around the property and transported to the baths and fountains through underground pipes.

The bathing block

The changing room

The design of the baths was symmetrical on the central axis, with male-only rooms on one side, female on the other, and the bathing rooms in the middle. Every bather’s first stop was the male or female apodyterium (changing room). Here, visitors could store their clothes in individual cubbies. Many wealthy Romans would bring an enslaved person with them to watch over their belongings, as items were sometimes stolen from the changing rooms. Their next step was to oil their bodies prior to exercise and, if wanted, they could either purchase a massage or be massaged by someone they enslaved.

Western Palaestra exedra looking into frigidarium, Baths of Caracalla, Rome (photo: Ethan Doyle White, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Palestrae (open-air exercise areas) and steam rooms

After this, guests would head to one of the two palestrae (open-air exercise areas). In these spaces they could stretch, lift weights, play ball, and in the case of the men, wrestle, or box. Some visitors would also run in the stadium. Post-exercise, the next stop was the steam rooms. The baths are thought to have offered both wet steam rooms (sudatoria) and dry heat rooms (laconica). Visitors (or an enslaved person) would then scrape away the oil on their bodies to cleanse themselves with an item known as a strigil, or scraper. This would help remove the dirt and sweat from their bodies before entering the pools.

Caldarium with a view toward the tepidarium and frigidarium beyond, Baths of Caracalla, Rome (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Hot baths

After this, it was time to move to the hot baths. In this complex, the caldarium was a large circular room topped with a 130-foot dome, which is nearly as large as the Pantheon. However, unlike the Pantheon, which had an oculus or open window in the center of the dome, the caldarium was lit by three-tiers of large glass-covered windows which faced onto the gardens outside. The windows of both the caldarium and steam rooms faced the southwest where they could receive the most sunlight, and therefore additional warmth throughout the day, consciously employed by the architects. One bathing pool was in the center of the caldarium (“A” on the plan) under the dome while seven others were in rectangular niches encircling most of the room.

Warm baths

Once finished, one would proceed to the tepidarium (warm baths). This was a smaller space with only two pools and served as a transitionary area between the hot and cold baths. Some Romans would even use this bath twice: both before and after the hot baths to help make the transition between the different temperature pools easier. The warm and hot baths were both heated by underground furnaces which would circulate hot air beneath the floors and in the walls.

Cold baths, fountains, and pools

Lysippos, Farnese Hercules (also Weary Hercules), 4th century B.C.E., later Roman copy signed “Glykon of Athens” (in Greek letters), c. 216 C.E., 10 feet 5 inches high, found in the ruins of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome in 1546 (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples)

The frigidarium (cold baths) was located in the grandest hall of the complex. The rectangular hall was topped by three massive groin vaults more than 100 feet tall. Both the walls and floor were clad in expensive marble, and there were four colossal marble columns on each of the short ends of the hall. A pathway was left open between the middle two columns on each end of the room, but sculptures were placed between the others, including a marble copy of Lysippos’s Weary Herakles statue, known today as the Farnese Herakles.

Additionally, the hall contained fountains and pools, two of which are now located in fountains in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome (with later additions) and one of which is now at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. Clerestory windows helped to light the vast space. Four plunge pools were located in the corners of the room, but the hall also served as a meeting place and main passageway to other areas of the baths. The two pools closest to the natatio (swimming pool), were separated from it only by waterfalls which created a glistening wall between the two spaces. The natatio could be entered between columns located beneath a monumental archway on the northeast side of the frigidarium.

Natatio (swimming pool), Baths of Caracalla, Rome (photo: ctj71081, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Unlike the other bathing areas, the natatio was open to the sky. It was surrounded on four sides by walls approximately 65 feet tall. The pool itself was approximately 164 feet long and 72 feet wide, nearly identical to the size of Olympic swimming pools today. The southwest wall was mostly open to the frigidarium, but the northeast wall was divided into three sections separated by colossal gray granite columns. Part of the wall functioned as a nymphaeum, creating the effect of a waterfall. The areas in between were filled with niches and statuary and clad in marble in a way that resembled the scaenae frons (architectural stage façade), of a Roman theatre. The pool itself was approximately three feet deep and was a place for both exercise and socializing. There was even a game board carved into the marble of one of the blocks surrounding the pool where people could sit and play together.

The baths were said to accommodate 1,600 bathers at one time and up to as many as 8,000 each day. There was once a second story over some parts of the building, as evidenced by staircases, but the remains at this level are so incomplete that the function of the upper story is unknown.

The grandest baths in the city

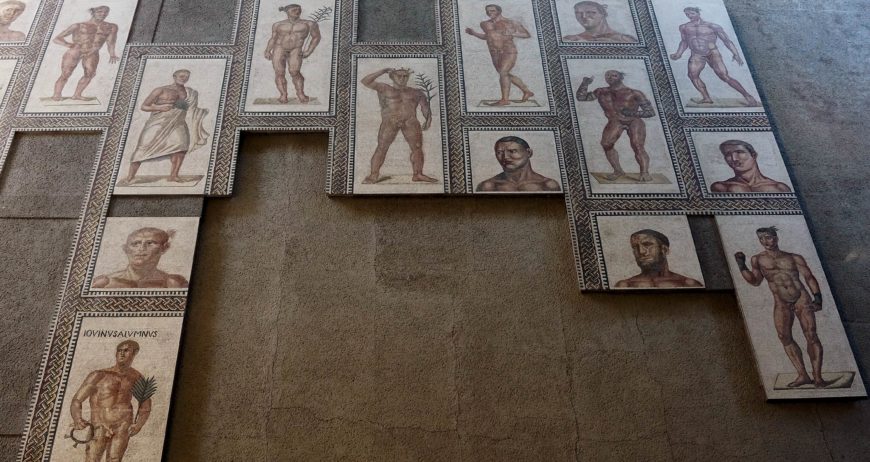

At the time when they were constructed, the Baths of Caracalla were the largest and grandest in the city. Caracalla spared no expense with the decorations. There were precious imported marble columns and slabs to cover the floors and walls, extensive (and expensive) marble sculptures, and colorful mosaics. Some of the vaults were covered in glass-paste mosaics, others in decorative stuccowork. Very little of the marble decoration survives, though some small pieces can still be seen on the walls. Many of the floor mosaics are still on site today including colorful geometric patterns, black and white seascapes. Mosaics of athletes originally in the palestrae are now located in the Vatican Museums.

The overall design of the building was one of opulence, from the soaring vaults to the marble covered walls and colored mosaics. Sunlight streaming through the windows once reflected off the pools and fountains, sending sparkles dancing across the highly polished marble and glittering glass mosaics. The public areas of the complex were meant to dazzle, but a large portion of the structure was actually hidden from view.

The service areas

The Baths of Caracalla sit atop a large series of subterranean chambers. These rooms and hallways were like a small city all by themselves. Together, the known tunnels are more than a mile in length, though there are others still unexcavated. The barrel-vaulted halls were wide enough for horse-led carts to transport wood to the approximately 50 underground furnaces. One tunnel connected directly to the Via Antonina to allow carts to enter the underground areas easily and out of sight of the guests. The furnaces consumed approximately 10 tons of wood each day, fires that were stoked all day long by enslaved people to keep the caldarium and steam rooms hot. Hot air from the furnaces would circulate through a hypocaust system, an open space a few feet high located above the underground rooms, but below the flooring of the bathing rooms. This space contained rows of stacks of bricks known as pilae. Air would circulate between them at this level and move upwards through pipes in the walls. This was aided by a hydraulic system which permitted a controlled distribution of air through the pipes.

In addition, there were large storage rooms for wood, linens, oil, and other supplies. Staircases led from the underground areas into the baths themselves so enslaved people could supply the visitors with linens and oil. Hidden corridors and stairs were located in many of the walls and piers (large, rectangular supports) out of view of the bathers. There was also an underground Mithraeum, a sanctuary dedicated to the god Mithras.

Later History

The baths served as inspiration for other structures such as the Baths of Diocletian and the Basilica of Maxentius in Rome and even more modern buildings like the old Pennsylvania Station in New York City. The baths remained in operation until 537 C.E. when Ostragoths destroyed the aqueduct leading to the structure during a siege of Rome, ending the water supply and leading to its abandonment. Over the years, the complex fell into disrepair due to earthquakes and was later used as a quarry for building materials in the late medieval and Renaissance periods.

During the Italian Renaissance, the structure was excavated with the intention of obtaining sculptures and other finds for private and the papal collections. Scientific excavations did not begin until the 19th century. Though little to none of the grand marble revetment remains and most of the vaults and ceilings no longer exist, you can still get a sense of massive scale when visiting the baths today.

Additional resources:

Virtual Walk-through of the Reconstruction of the Baths of Caracalla

Filippo Coarelli, “Forum Holitorium, Forum Boarium, Circus Maximus, and the Baths of Caracalla,” In Rome and Environs: an archaeological guide. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), pp. 307–31.

Janet DeLaine, “Roman Baths and Bathing.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 6 (1993): 348–58.

Janet DeLaine, The Baths of Caracalla: A Study in the Design, Construction, and Economics of Large-Scale Building Projects in Imperial Rome (Portsmouth, RI: JRA, 1997).

Garrett G. Fagan, Bathing in Public in the Roman World. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002).

Maryl B. Gensheimer, Decoration and Display in Rome’s Imperial Thermae: Messages of Power and Their Popular Reception at the Baths of Caracalla. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Fred S. Kleiner, A History of Roman Art. (Victoria; Thomson/Wadsworth, 2007), pp. 242–45.

Miranda Marvin, “Freestanding Sculptures from the Baths of Caracalla.” American Journal of Archaeology 87, no. 3 (1983): pp. 347–84.

Roman Baths and Bathing: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Roman Baths Held at Bath, England, 30 March-4 April 1992. Journal of Roman Archaeology. Supplementary Series No. 37. Portsmouth, R.I: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1999.

Frank Sear, Roman Architecture. (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1983), pp. 257–59.

Fikret K. Yegül, “Chapter 16: Roman Imperial Baths and Thermae.” In A Companion to Roman Architecture, edited by Roger B. Ulrich and Caroline K. Quenemoen. (Oxford, U.K.: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2013), pp. 299–323.