April 2019 fire at Notre Dame de Paris (Photo: Milliped , CC BY-SA 4.0)

The fire

The blaze that engulfed the Cathedral Notre Dame on the small Island known as the Île de la Cité in Paris in April 2019 was a terrible tragedy. Though it may not give us much comfort to learn that the total or partial destruction of churches by fire was a fairly common occurrence in medieval Europe, it does provide some perspective. For example, a fire destroyed most of Chartres Cathedral in 1020 (and again in 1194), in the city of Reims, the cathedral was badly damaged in a fire in 1210, and at Beauvais, the cathedral was rebuilt after a fire in the 1180s. The list goes on and on.

During the medieval periods of the Romanesque and the Gothic (c. 1000-1400), church fires were less frequent than they had been previously due to the development of stone vaulting (which began to replace the timber ceilings commonly found in European churches). But even a stone vault, as we saw at Notre Dame in Paris, is itself protected by a timber roof (sometimes rising more than 50 feet above the stone vaulting and pitched to prevent the accumulation of rain and snow), and this is what caught fire.

Art historian Caroline Brazelius, who has worked on the building for years said, “between the vaults and the roof, there is a forest of timber” — old, dry, porous, and highly flammable timber. Still, photographs of the interior show at least some of the stone vaulting survived the recent fire. The builders of Notre Dame used Parisian limestone, but, as Brazelius notes “when it’s exposed to fire, stone is damaged. It doesn’t actually burn….It becomes friable. It chips, and it’s no longer structurally sound.”

Built, modified, rebuilt, and restored

Churches are often an amalgamation of architectural styles, the result of building campaigns and modifications undertaken at different times, some due to fire, some due to the desire for what a new style represents, and some due to (often inaccurate) restoration efforts. And on a single site, churches were often built and rebuilt — and this is the case with Notre Dame in Paris. Before the Gothic-style church was built, a Carolingian church occupied the site (it was destroyed during the 9th century Viking invasions), and before that, a 6th century Merovingian Church stood on the site.

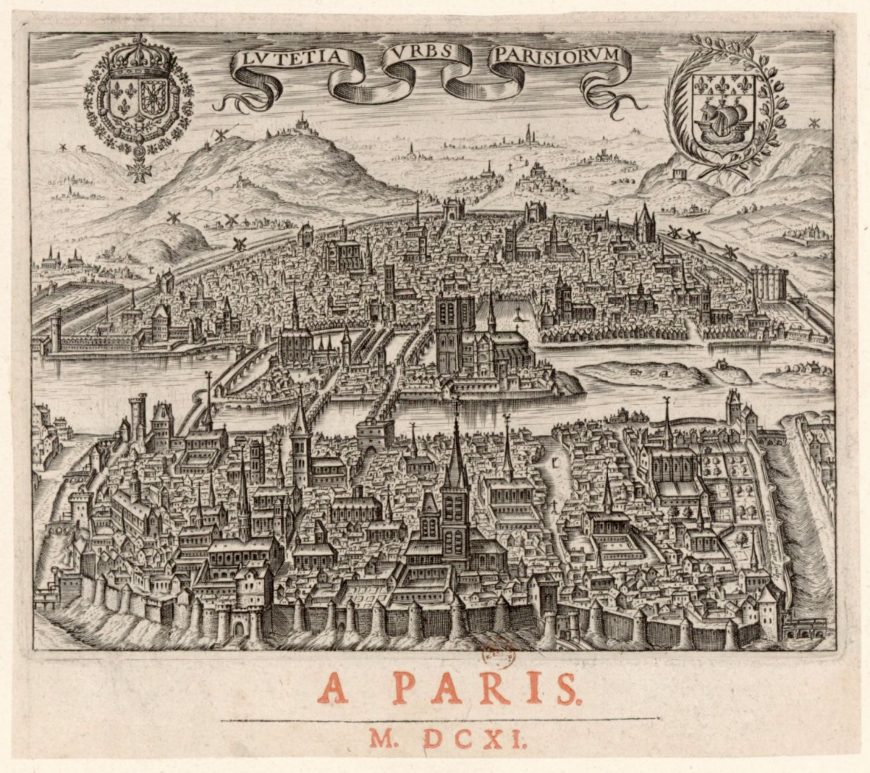

Léonard Gaultier, View of Paris, 1607, engraving ( Bibliothèque nationale de France )

If we go back further, to the pre-Christian era, Julius Caesar’s armies famously conquered much of what we call France today (Roman Paris dates back to 52 BCE). Archaeological evidence suggests that a pagan temple and then a Christian basilica were built on this site. The ancient Romans also built a palace for the emperor on the Île de la Cité, and after the Roman empire collapsed, Clovis I, King of the Franks (who converted to Christianity) established his palace there as well. The Île de la Cité would remain the location of a royal residence until the 14th century. As one historian has noted, “Notre Dame … was not only a religious but also a royal monument that displayed the might of the church and the monarchy, each enhancing the power of the other.” [1]

The Gothic Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris took nearly 100 years to complete (c. 1163-1250) and modifications, restorations, and renovations continued for centuries after. The early Gothic style employed at the beginning of the campaign became outdated and the later Gothic style, the Rayonnant, became fashionable and can be seen in the transepts. The crossing spire that the world watched fall while engulfed in flames was a reproduction created during a 19th-century restoration campaign.

In the following centuries, the church (and its sculptural decoration) survived multiple episodes of intentional destruction: during the Protestant Reformation (due to Protestant objection to religious imagery), and during the revolutions of 1789 and 1830 (because of the church’s close association with the monarchy). It remained in a neglected state until Victor Hugo’s novel, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) revived popular interest the building.

As of this writing, just a few days after the April 15th blaze, evaluation of the damage caused by the fire is only just beginning, but a reported one billion dollars has been already been raised to support the reconstruction of Notre Dame de Paris.

Additional resources

The Cathedral’s construction (official website of Notre Dame de Paris)