Belém Monstrance, attributed to Gil Vicente, 16th century, gold and polychrome enamels, 73 x 32 cm x 26 cm (MNAA National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon)

One of the most celebrated objects in Lisbon’s Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga is, without a doubt, the Belém monstrance. Measuring about an arm’s length (73 cm in height), it is made out of shimmering gold that has been molded into the most intricate, delicate shapes, and enhanced with brightly colored enamels. The monstrance looks like a miniature tower in the Gothic style, built out of elements such as tracery, pinnacles, and flying buttresses that rise up towards the heavens. Glistening in the dusk of the museum space, it appears like a Catholic treasure.

Christ’s twelve Apostles kneel in a circle before the container for the host, Belém Monstrance (detail), attributed to Gil Vicente, 16th century, gold and polychrome enamels, 73 cm x 32 cm x 26 cm (MNAA National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon; photo: , CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Belém monstrance was designed as a functional object in the Catholic liturgy: its purpose was to contain the consecrated host, the holy wafer that for Catholics is the body of Jesus Christ. Stored in the cylindrical glass container on the monstrance, the host is shown being venerated by the colorful kneeling figures of Christ’s twelve Apostles, grouped in a circle around it.

Top portion of the Belém Monstrance, with the dove and God the Father, attributed to Gil Vicente, 16th century, gold and polychrome enamels, 73 x 32 x 26 cm (MNAA National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon; photo: , CC BY-SA 3.0)

Above the cylinder, we find a white dove, symbolizing the Holy Spirit, and at the top, the seated figure of God the Father. Thus, the monstrance represents, in an upward sequence, the Holy Trinity. Yet its great significance as a Portuguese work of art derives from the way this spiritual theme is bound up with more worldly concerns. As the inscription on the base of the object proclaims, it was commissioned in the early 1500s by the Portuguese king Dom Manuel I, who ordered it to be made from gold received as a tribute from Kilwa in eastern Africa. The Belém monstrance, therefore, embodies a pivotal moment in Portuguese overseas expansion and colonization, and is an emblem of the artistic and imperial flourishing of Portugal under Manuel’s reign.

Dom Manuel I

Dom Manuel I became King of Portugal in 1495, succeeding his cousin João II, who died without a male heir. Unlike his predecessor, King Manuel was less concerned with internal power struggles and this enabled him to focus on different matters: administrative reform, and his international image as the ruler of a Portuguese global empire. The Portuguese expansion, which had been initiated in the early fifteenth century, took flight under his kingship. Manuel sponsored the two expeditions of Vasco da Gama that resulted in establishing the sea route between Europe and India. Also during his reign, Pedro Álvares Cabral landed on the coast of Brazil, beginning the Portuguese colonization of this territory. Similarly, Gaspar Corte Real established a Portuguese presence in Newfoundland, and Afonso de Albuquerque violently confirmed Portuguese hegemony in the Indian Ocean.

An example of the Manueline style: the south portal by João de Castilho, exterior of the Church of Santa Maria de Belém, a portion of the Jerónimos Monastery, 16th century, Lisbon, Portugal (photo: Daniel VILLAFRUELA, CC By-SA 3.0)

At home, Manuel expelled Portuguese Jews and Muslims from the Kingdom, forcing them into conversion or exile. The loss of tax income due to this policy was more than compensated for by the wealth generated through new overseas territories and trade, particularly sugar production on the island of Madeira, as well as through Manuel’s improved management of Crown lands. his reign have become associated with the splendors of monumental religious architecture, built under his patronage in the “Manueline” style. Manuel was also a generous gift-giver, a practice he used to enhance his position.

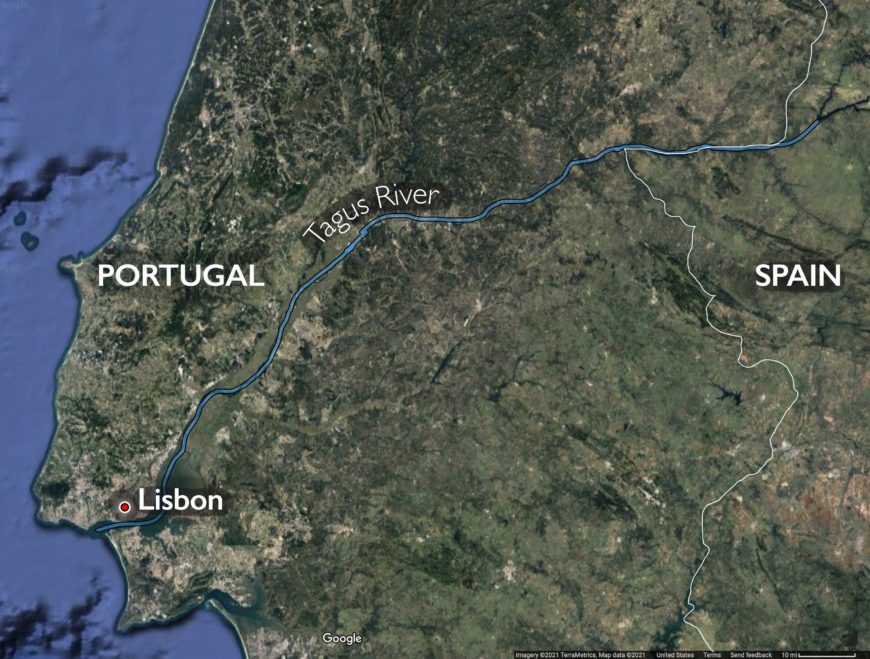

The Belém Monstrance fits these patterns of patronage: Manuel bequeathed the Monstrance to one of the most important of the religious foundations established during his reign, the Hieronymite Monastery of Santa Maria de Belém. As we will see, the monstrance also foregrounds the king’s new title, “By the Grace of God, King of Portugal and of the Algarves on this side of the sea and the other, in Africa, Lord of Guinea and of the Conquest, Navigation, and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, India, etc.” [1] Manuel had extended the royal title with the latter part (‘and of the conquest … etc.’) in 1499, around the time of the return of Vasco da Gama from his first Indian voyage, whose ships were greeted with a lavish reception in Belém, the destination of the monstrance. All of this helped in making Belém, at the time a village about 7 kilometers to the west of Lisbon’s historical core on the bank of the river Tagus, a site of vital importance to Manuel and the royal Avis dynasty, who also came to use the Monastery as their mausoleum.

The Belém Monstrance fits these patterns of patronage: Manuel bequeathed the Monstrance to one of the most important of the religious foundations established during his reign, the Hieronymite Monastery of Santa Maria de Belém. As we will see, the monstrance also foregrounds the king’s new title, “By the Grace of God, King of Portugal and of the Algarves on this side of the sea and the other, in Africa, Lord of Guinea and of the Conquest, Navigation, and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, India, etc.” [1] Manuel had extended the royal title with the latter part (‘and of the conquest … etc.’) in 1499, around the time of the return of Vasco da Gama from his first Indian voyage, whose ships were greeted with a lavish reception in Belém, the destination of the monstrance. All of this helped in making Belém, at the time a village about 7 kilometers to the west of Lisbon’s historical core on the bank of the river Tagus, a site of vital importance to Manuel and the royal Avis dynasty, who also came to use the Monastery as their mausoleum.

The base with inscription and the “knot” above it on the stem, Belém Monstrance (detail), attributed to Gil Vicente, 16th century, gold and polychrome enamels, 73 cm x 32 cm x 26 cm (MNAA National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon; photo: , CC BY 3.0)

The iconography of the monstrance

The monstrance is a prime example of what art historians have called micro-architecture: it looks like a building on a miniature scale and has many stylistic and iconographical features in common with the monumental architecture that was produced under Manuel’s patronage. On the base, we find an inscription that highlights the king’s agency: “O MVITO. ALTO. PRICIPE. E. PODEROSO. SEHOR. REI. DO. MANVEL. I. A. MDOV. FAZER. DO. OURO. I. DAS. PARIAS. DE. QILVA. AQVABOV. E. CCCCCVI.” (The very high prince and powerful lord king D. Manuel I had it made from the first gold of the tribute of Kilwa. It was finished in 1506.) The solid gold foot is divided in six lobed compartments which are decorated with organic elements executed in gold and enamel.

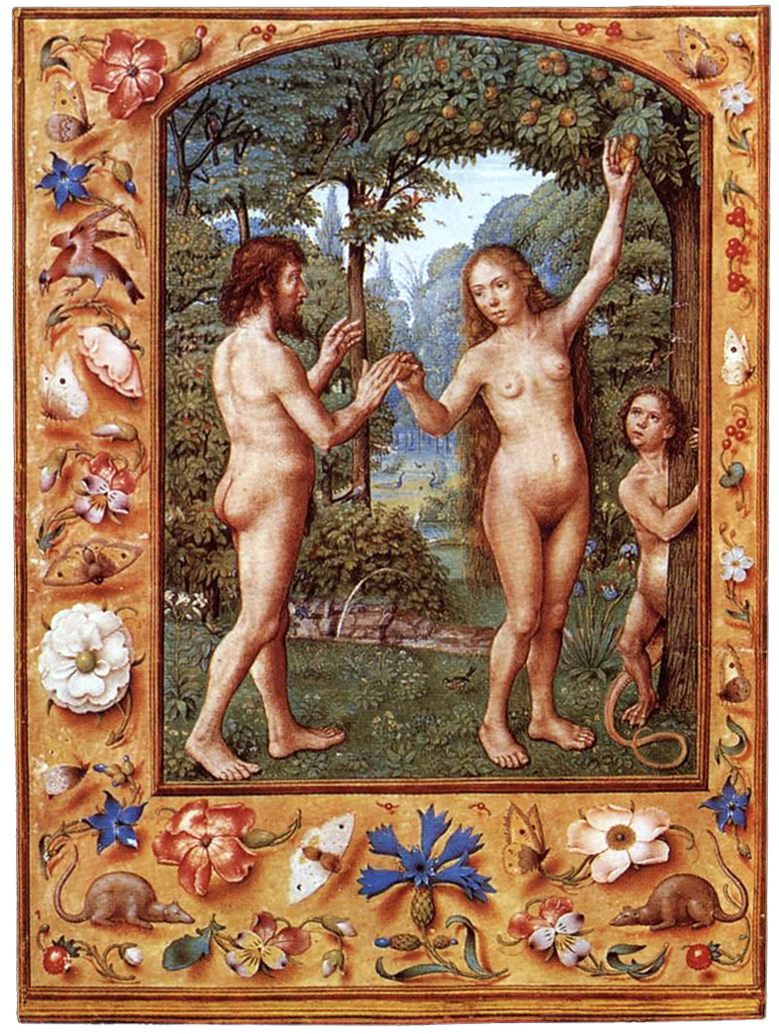

A page from the Grimany Breviary showing Adam and Eve, with plants and small animals in the margin. Flemish miniaturist, Adam and Eve, from the Grimany Breviary, c. 1510–1520 (Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, MS. lat. I. 99)

The colorful birds, flowers, and mollusks are strikingly similar to the marginal illustrations of some of the best illuminated manuscripts produced in the same period, not only for the Portuguese aristocracy but for other European patrons as well.

Up on the stem, there is another more overt reference to the figure of the king: the so-called “knot” (seen in the photo above with the inscription) carries six armillary spheres, scientific instruments used in navigation which Manuel adopted as a personal symbol and which often appear on portals and door frames in Manueline architecture. In such liminal locations, it alludes to the mediating role of the king between the terrestrial and spiritual realms. Here, the spheres do exactly that: above them is the platform with the Apostles and the consecrated host, subtly supported by vine ranks that symbolize the Eucharist: this plant refers to the wine that is transubstantiated into Christ’s blood during the celebration of the Mass.

Belém Monstrance, attributed to Gil Vicente, 16th century, gold and polychrome enamels, 73 cm x 32 cm x 26 cm (MNAA National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon)

The higher we move, the closer we get to the divine, which is not only expressed through the iconography but also through the use of materials: solid and heavy at the base gradually transforms into light and airy at the top. The central part of the monstrance is arguably the most exuberant, with the highly detailed and individualized figures of the twelve kneeling Apostles flanked by two slender turrets. The turrets not only contain music-making angels but also, hardly visible on the inside, Mary and the angel Gabriel, representing the Annunciation or the moment of Christ’s incarnation as man.

The top level, consisting of a double baldachin that contains the Holy Spirit, God the Father, and a Latin cross, is unparalleled in its use of countless elegant Gothic pinnacles and spires. This part, in between the Dove and the enthroned figure of God, also carries tiny figures of Old Testament prophets, which form an unexpected link with the armillary spheres in the monstrance’s lower regions: prophesying the coming of the Messiah, these figures also relate to the name of the king, whose name, Manuel (Hebrew for ‘God is with us’) is interpreted in the Gospels as the fulfillment of scripture through the incarnation of Jesus Christ. Through this connection of the prophets with the name of the king, the Monstrance highlights the pious images that Manuel liked to project of himself, as a prophet, protector, and promoter of Christendom.

Gil Vicente, poet and goldsmith

The artist that the king entrusted with the Kilwa gold was very likely Gil Vicente, poet, goldsmith, and courtier. In the past, there has been some debate whether the famous poet and playwright could be the same as the creator of the Monstrance, but now there is little doubt among scholars. Vicente worked for king Manuel, Queen Eleonor, and the later king João III. At the time he began work on the Monstrance, he also regularly staged plays at the royal court in Lisbon. In his many roles, Gil Vicente was an important cultural figure, whose work in stagecraft and writing responded directly to the immense changes to Portuguese society brought on by the country’s maritime expansion. While his written work, mostly consisting of comedies and farces, shows some critical reflection on the vanity of the imperial project, the gold of the Monstrance reflects the king’s ambitions.

The gold

As the inscription at the base reminds the viewer, the gold of the monstrance was a tribute from Kilwa, a sultanate based on an island off the coast of present-day Tanzania. Threatened with military violence, the Sultan of Kilwa was forced to hand over the gold to Vasco da Gama in recognition of the overlordship of Manuel I. He entered into a contract with the Portuguese to pay an annual sum. When the Portugese arrived in East Africa and other places local rulers would often seek alliances with the newcomers and accept vassalage, as the ruler of Kilwa did, to the Portuguese king in efforts to manage local power balances. The Kilwa payment was hailed by the Portuguese as of great symbolic significance: as sixteenth-century Portuguese chroniclers attest, Vasco da Gama took the gold to Lisbon where, with the contract signed by Kilwa, it was taken on a solemn procession through the city. Such a spectacle, of a diplomatic “gift” made by one far-away king to the ruler of Portugal, greatly enhanced Manuel’s position at home.

This painting representing the Adoration of the Magi imagines the gifts of the Wise Men as examples of Gothic micro-architecture. Gregório Lopes and Jorge Leal, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1525, part of the retable for the Lisbon church of São Francisco, Lisbon (MNAA Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon; photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The gold has been used strategically by the artist: the Monstrance has been constructed from different alloys (a mixture of metals), and the purest gold has been applied to some of the symbolically most important figures: God the Father, several Apostles, and the Cross on top. This underlines the spiritual significance attributed to the material. In medieval and Renaissance art, gold often symbolizes the divine. Yet its appeal went beyond Europe: gold was a material that spoke across cultural divides. For this reason, art historians have pointed out that the Belém monstrance, crafted out of gold offered by a distant king, was like the gifts of the Three Wise Men to baby Jesus. Balthazar, one of the Three Kings, was often associated with Africa and shown as a Black man in contemporary imagery. In the Monstrance of Belém (Portuguese for Bethlehem, where Jesus was born), the heathen kings from faraway lands came to pay homage to Christ in the form of the most holy Sacrament. In this way, the Belém Monstrance marries the spiritual and worldly ambitions of Dom Manuel I, representing the king’s alliance with Jesus Christ and ambition to be recognized as a global Catholic ruler.

The Belém Monstrance is an object of extraordinary artistry that responds to events taking place in Portugal and to its overseas expansion. The result of the King’s patronage, it presents Manuel as a mediator between heaven and earth. Gil Vicente’s design re-interprets the Kilwa gold tribute, which was surely offered for pragmatic reasons, as a sacred gift acknowledging Manuel’s worldly and spiritual power.

Additional resources:

The Belém monstrance on the website of the MNAA

The Belém Monstrance on Google Arts and Culture

Exhibition catalogue dedicated to the Monstrance: Maria Leonor d’Orey and Luísa Penalva (eds.), A Custódia de Belém: 500 Anos (Lisbon: Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 2010)

Zoltán Biedermann, “Three Ways of Locating the Global: Microhistorical Challenges in the Study of Early Transcontinental Diplomacy,” Past & Present vol. 242 (2019), pp. 110–141

Mia M. Mochizuki, “The Reliquary Reformed,” Art History vol. 40, issue 2 (2017), pp. 430–449

Isabel dos Guimarães Sá, “The Uses of Luxury: Some Examples from the Portuguese Courts from 1480 to 1580,” Análise Social vol. 44 (2009), pp. 89–604