Ben Ezra Synagogue, founded 1006, rebuilt 1893, Fustat (‘Old Cairo’), Egypt (Diarna)

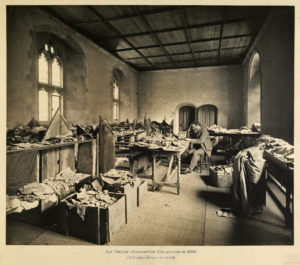

Cambridge scholar Solomon Schechter was among the many scholars to uncover and begin to decipher the trove of documents in the Cairo Genizah. Solomon Schechter studying the fragments of the Cairo Genizah, c. 1898 (Cambridge University Library)

Imagine discovering a treasure trove of hundreds of thousands of documents, some as old as the 11th century. This happened in the 19th century when scholars and collectors recovered what is now called the Cairo Genizah—roughly 210,000 documents pertaining to life in Egypt from the 11th–19th centuries. [1] They were discovered in a storeroom of the Ben Ezra Synagogue, a Jewish house of worship in Fustat (Old Cairo), Egypt. Although best known for the documents found there, the synagogue (the focus of this essay) is a remarkable monument in its own right that provided a center for Jewish communal worship in Egypt for centuries.

The Ben Ezra Synagogue was founded in 1006, and has been revered from that time to the present (today it functions primarily as a museum). Its architecture and decoration reveal the changing history and visual culture of Egyptian Jews, from periods of cultural and economic growth, to destruction, abandonment, and renewal. Throughout its history, the synagogue’s decoration shows the community’s desire to visualize their connections to the local environment and its visual culture, as well as to celebrate their unique Jewish presence within a dominant Muslim society.

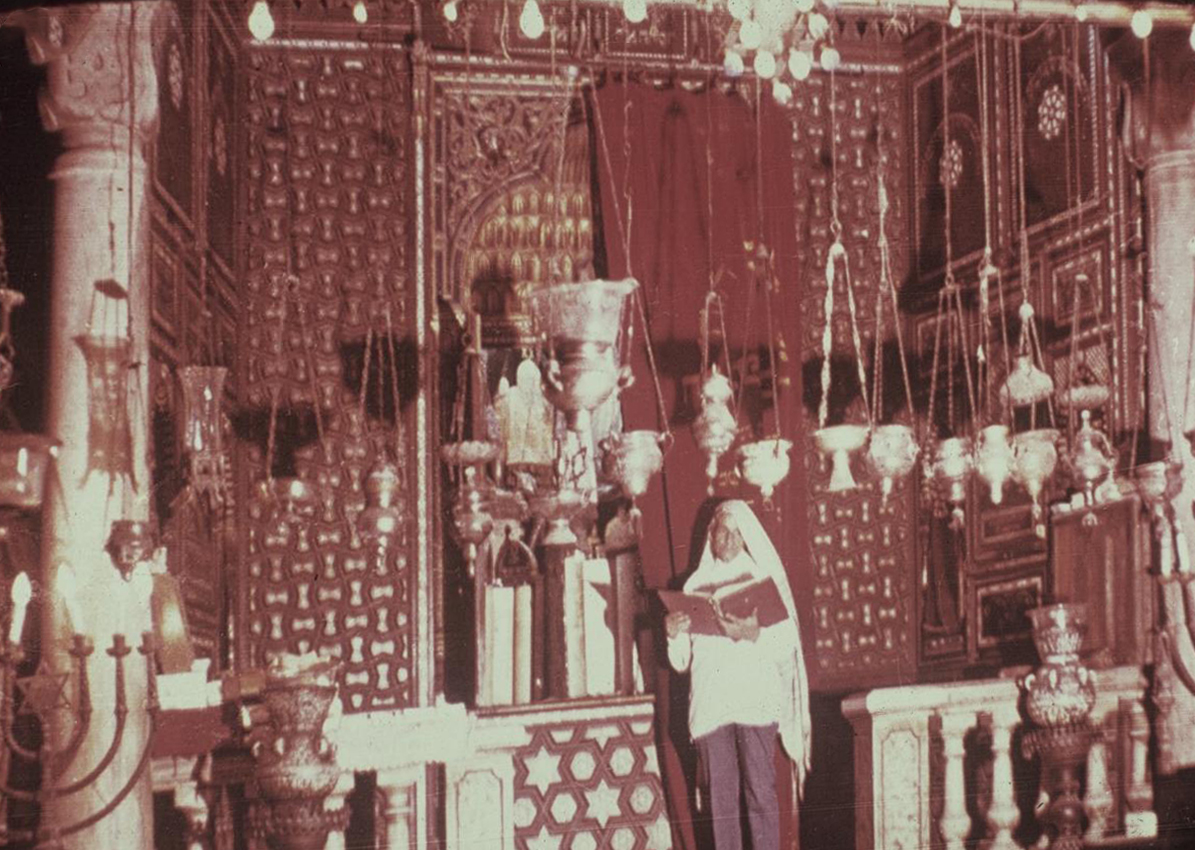

Ben Ezra Synagogue interior, c. 1950–60 (Center for Jewish Art)

The Jews of Fustat and the Ben Ezra Synagogue

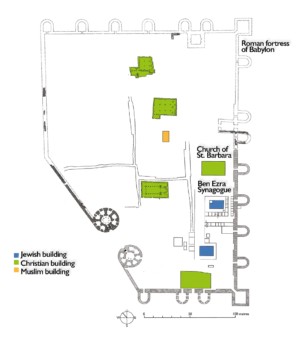

Map of Fustat c. 12th century, including the Ben Ezra Synagogue and other religious buildings (after drawing by Zina Cohen, based on Kate Spence, Peter Sheehan, and Charles le Quesne, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In 641 C.E. Muslim forces conquered one of the last remaining Eastern Roman “Byzantine” strongholds in Egypt (known as the Roman fortress of Babylon). They transformed the fortress and the adjacent Arab camp used for the siege of the fortress into the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule—the city of Fustat. Within the walls of the fortress, the new Muslim rulers encountered vibrant Jewish and Coptic Christian populations. Even as the Fatimids established a new capital city to the north in Cairo (‘new Cairo’) in 969, many members of the minority Jewish and Christian populations remained in Fustat and, despite intermittent periods of violence and destruction, they thrived. It was around this time, in the late 10th century, that the Ben Ezra Synagogue was first built.

Only a few years after the synagogue’s foundation, it was destroyed when Egypt’s Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim ordered the destruction of all Jewish and Christian houses of worship within his domains around 1013. Within roughly 20 years, however, the Jewish community rebuilt their sacred institution, and it became the spiritual center of one of the most prosperous and dynamic Jewish communities of the medieval Afroeurasian world, and a home to the great Jewish rabbi, philosopher, and physician Moses Maimonides.

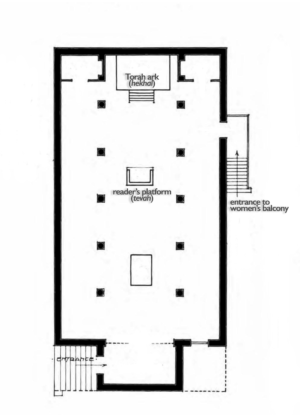

The original synagogue, and its mid-11th-century renovation, was built as a two-story basilica with side aisles. The nave was separated from the aisles by twelve marble columns which supported two balconies for women—the earliest yet discovered—accessed through a separate staircase on the exterior of the synagogue.

In its architectural plan it followed the arrangement of local Coptic churches within the Roman fortress, such as the nearby Church of St. Barbara. While it might seem surprising that a Jewish community would adopt Christian religious architectural and artistic forms in the construction and adornment of their own religious spaces, this was common in Jewish communities around the world. Beyond two essential elements in synagogue architecture—a reader’s platform (tevah), from which the clergy led the service as well as read from the Torah during the weekly liturgy, and a Torah ark (hekhal) to house the scrolls of the Torah—the design of a synagogue leaves ample room for creativity. And so for centuries, Jewish communities have adopted and adapted from local architectural traditions. This is precisely what we find in the Ben Ezra synagogue.

Over time, wealthy Jews moved to more spacious neighborhoods in the new city of Cairo, and the area surrounding the synagogue deteriorated. Nevertheless, and despite a dwindling community, the Ben Ezra Synagogue was maintained through pious donations. By the 15th century, the synagogue’s role in the Jewish community had declined, and as a result was only used for worship on Shabbat. Though it endured through the 16th and 17th centuries, even as many other synagogues in Fustat and Cairo ceased to exist, it fell into disrepair. The synagogue was entirely rebuilt in the early 1890s and restored again in the early 20th century. The synagogue as rebuilt in the 19th century was made almost entirely out of new materials, preserving and reusing only the original synagogue’s wooden dedicatory furnishings and some small marble columns in the second story. However, based on analysis of documents from the Cairo Genizah (such as inventories and reports of work in the synagogue), the architectural plan today remains largely faithful to the earlier medieval building.

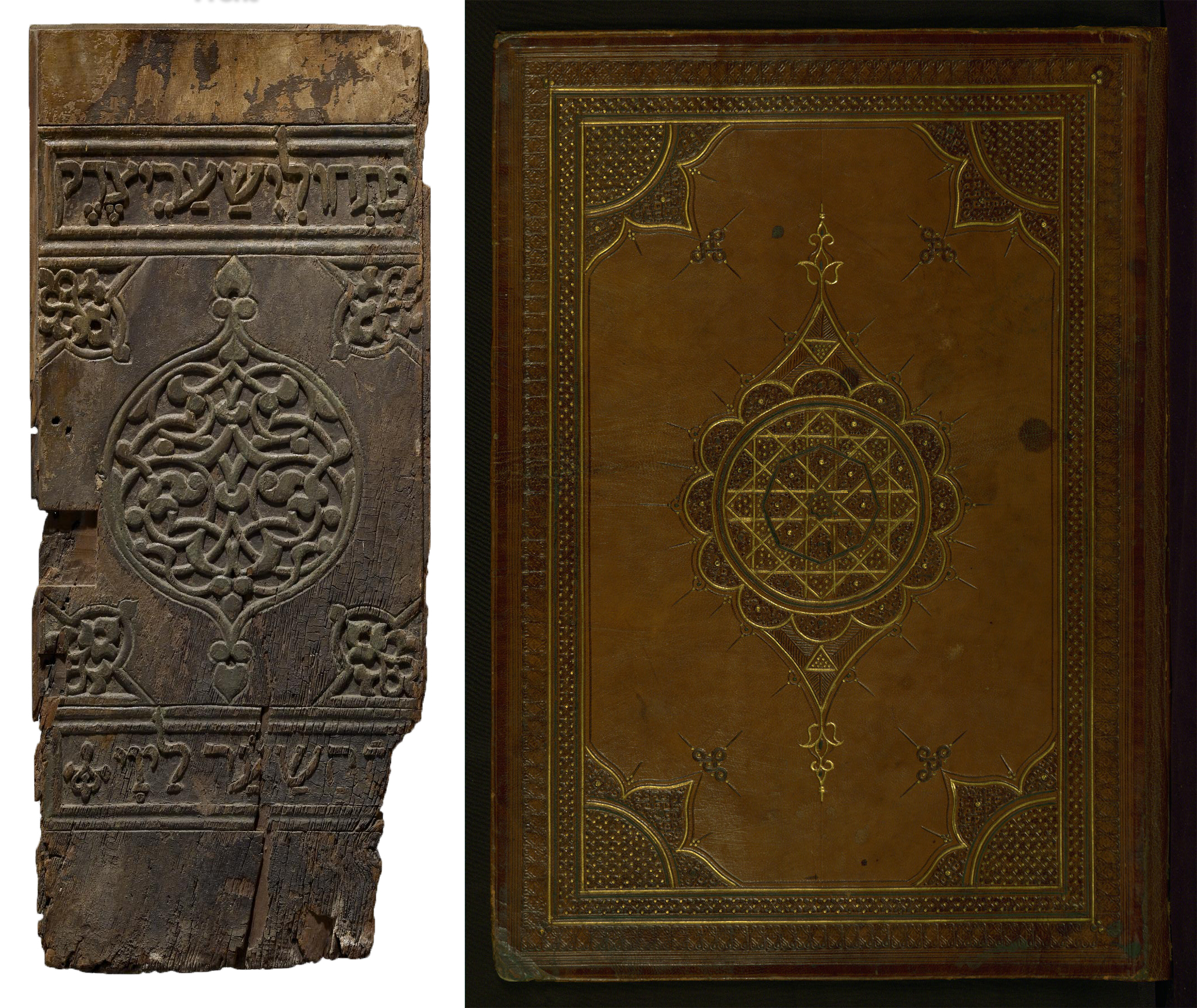

Panel from a Torah Ark door, 11th century with later carving and paint, wood (walnut) with traces of paint and gilding, Ben Ezra Synagogue, Fustat, Egypt, 87.3 x 36.7 x 2.5 cm (The Walters Art Museum and Yeshiva University Museum)

Sacred furnishings

Torah Ark doors

Among the documents from the Cairo Genizah are records of the furnishings and decorations of the Ben Ezra Synagogue at its height from the 11th–13th centuries. These sources describe a remarkable number of Jewish liturgical objects, in particular works related to the protection and adornment of the Torah—mantles and curtains, and elaborate silverwork, including Torah crowns, and finials. Their sheer number and the preciousness of the materials described (including fine gold and silver threads, rare silks, and precious metals), all attest to the wealth of the medieval Jewish community of Fustat. While most of these furnishings are no longer extant, several finely carved and inscribed wooden artifacts survive that once adorned the synagogue’s Torah ark (a cabinet that housed the Torah scrolls and marked a boundary between the congregation and a threshold to the divine).

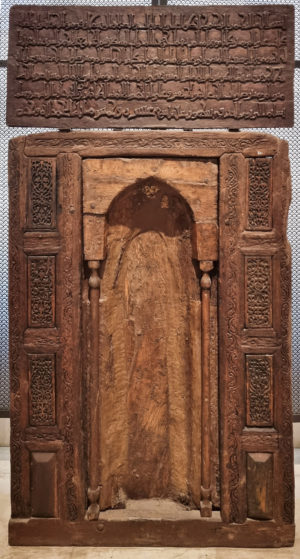

Left: Torah Ark door (exterior face), 11th century with later carving, paint, and gilding, Ben Ezra Synagogue, Fustat, Egypt, wood (walnut), 87.3 x 36.7 x 2.5 cm (The Walters Art Museum and Yeshiva University Museum); right: Qur’an, 14th century, Cairo, Egypt (The Walters Art Museum)

Of the three door panels that survive from the synagogue’s medieval Torah ark, one (now in the Walters Art Museum) can be securely dated to the 11th-century (though it includes ornament added centuries later). The door is inscribed on both sides at top and bottom with Hebrew verses evoking the door’s significance as a gateway to heaven: on the exterior, it reads “Open to me the gates of righteousness. . . . This is the gate of the Lord,” and on the interior, “May the Lord bless you and keep you . . . the Lord lift his Countenance onto you.” [2]

Carved into the exterior face of the panel, we see a central medallion with pointed terminations enclosing arabesque designs. In each of the four corners, similar intertwining foliate forms and terminations frame the center motif.

These decorative carvings (likely added during the 15th or 16th century), draw on designs popular in Egyptian Mamluk and Ottoman woodcarving and book binding, which commonly featured a similar largely undecorated field with central medallions and corner ornaments (see the comparison above). In the 19th century, the Torah ark doors were renewed with the application of pigment (no longer visible to the naked eye), including red, green, and purple-brown paint and gilding. Rather than replacing the Torah ark doors with new furnishings in the most up-to-date fashions, their reuse and renewal reflects the respect for the original carvings and the sanctity they had acquired.

Wooden mihrab with dedicatory inscription and inset carved wooden panels, 1125, al-Azhar Mosque, Cairo, Egypt (Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0)

A rare local resource, wood constituted a prized material in Egypt for decoration, and was therefore a fitting material to adorn houses of worship. Just as wood constituted the primary medium of decoration in the Ben Ezra Synagogue, so too were wooden furnishings employed to demarcate the holy thresholds of Coptic and Muslim religious spaces in Fustat and Cairo. In coptic Christian churches intricate wooden sanctuary screens, fitted with delicately carved wooden panels, demarcated the separation between the nave and the holy sanctuary and carved and painted wooden ciboria (canopies) surmounted the holy altar. Wood was similarly selected for the adornment of Cairo’s mosques. The qibla wall included delicately carved wooden mihrabs, as in the wooden mihrab from the al-Azhar mosque in Cairo, as well as carved wooden minbars.

As we can see from these examples, though coming from different religious traditions, these woodcarvings often shared a common vocabulary of artistic forms and techniques, likely fostered by mixed workshops, consisting of Muslim, Jewish, and Christian craftsmen. Even in cases where workshops were composed of artists of only one religion, they would have been located within the same quarter as other shops specializing in the same craft, and their proximity would have encouraged the exchange of ideas and forms.

“. . . a just reward from God, His deliverer. Such is the generation of those who turn to Him” (Psalm 24:5–6). Dedicatory inscription, 1220, wood, Ben Ezra Synagogue, Fustat, Egypt, 8.1 x 66.4 cm (Jewish Museum)

Synagogue dedicatory inscriptions

Between the 11th–19th centuries, members of the Ben Ezra Synagogue congregation donated carved wooden plaques to adorn the wooden Torah ark as well as the reader’s table. Like the ark doors, these panels include verses from the Book of Psalms as well as dedications, referring to the benefactors of the synagogue and their families. Placed around the Torah ark (the holiest site in the synagogue), the inscriptions acted as permanent testimonies of their donors’ devotion and called for their remembrance for perpetuity. Long after the donors were deceased, the wooden plaques remained, having attained a sanctified status themselves through their proximity to the Torah ark.

In their decoration, the wooden panels reflect a range of workmanship, with some texts incised, and some carved in relief. Other panels feature intricately carved foliate ornament. Despite this variation, each of the texts reflect great care in their execution.

Arched wooden fragment with dedicatory inscription, c. 1150, wood, Ben Ezra Synagogue, Fustat, Egypt, 147.5 x 33 cm (Louvre Museum)

Like the decoration of the Torah ark door, the ornament found on several of the Ben Ezra Synagogue’s dedicatory plaques (such as a fragment now preserved in the Louvre Museum), likewise reflected the decorative vocabulary then popular in Egypt. The Louvre’s fragment includes a network of carved geometric shapes densely filled with intricate crisscrossing vegetal forms surrounding a dedicatory text. In its complex latticework of shapes and vines, the carving closely resembles the intricacy of woodcarvings found in contemporaneous works produced for Egypt’s Muslim community.

Synagogue dedication inscription with graffiti, Ben Ezra Synagogue, Fustat, Egypt, 13th century, wood, 18.3 x 165.7 cm (The Jewish Museum)

In addition to the official inscriptions on the Torah ark and reader’s platform, the borders of several fragments preserve hastily carved names of visitors to the synagogue. These examples of sacred graffiti attest that worshippers recognized the carvings’ status as holy objects and hoped that by adding their own names to the collection of commemorated individuals, that they too might be remembered. All of the carved wooden boards from across the centuries of the synagogue’s history created a living memorial to the generations of members, donors, and visitors to the Ben Ezra Synagogue.

Throughout its history, the Ben Ezra Synagogue’s architecture and decoration has displayed the Jewish community’s artistic engagement with the local Coptic community and the broader visual traditions of Muslim Egypt. The synagogue’s wooden furnishings are precious, rare survivals from the synagogue’s decoration from its medieval period, which stand out as remarkable examples of the Jewish community’s celebration of their distinctive identity and their ongoing negotiation of their relationship with their neighbors.

Notes:

[1] From at least the 11th century, the Jews of Fustat placed their old texts in the genizah of the Ben Ezra Synagogue, a small attic storeroom of the synagogue. The texts included not only religious works (such as Bibles and prayer books), but also official government documents and everyday documents (such as shopping lists, marriage contracts, and scientific books). These provide scholars with an unparalleled window into the economic, cultural, and religious life of the Mediterranean world as well as the history of the synagogue itself and the community that worshiped there.

[2] Psalms 118: 19–20; Numbers 6: 24, 26.

Additional resources

American Research Center in Egypt, Egypt’s Synagogues: Past & Present

Diarna, Ben Ezra Synagogue at Cairo, Egypt

Ariel Fein, “Dedicatory inscriptions from the Ben Ezra Synagogue,” Africa and Byzantium, exhibition catalogue (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2023), p. 131, cat. 00a,b.

S.D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, 6 Vols. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

S.D. Goitein “The Synagogue and its Furnishings according to Genizah Records,” Eretz Israel 7 (1964): pp. 169–172.

Joshua Holo, “Synagogues under Islam during the Middle Ages,” in Jewish Religious Architecture: from Biblical Israel to Modern Judaism, edited by Steven Fine (Leiden: Brill, 2020), pp. 134–50.

Rebecca W. Jefferson, The Cairo Genizah and the Age of Discovery in Egypt: The History and Provenance of a Jewish Archive (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022).

Phyllis Lambert, ed., Fortifications and the Synagogue: the Fortress of Babylon and the Ben Ezra Synagogue (Montreal: Canadian Center for Architecture, 2001).

Vivian B. Mann, “Decorating Synagogues in the Sephardi Diaspora: the Role of Tradition,” in Synagogues in the Islamic World: Architecture, Design, and Identity, edited by Mohammad Gharipour (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), pp. 207–25.

Marina Rustow, The Lost Archive: Traces of a Caliphate in a Cairo Synagogue (Princeton University Press, 2020).

Ann Shafer, “Sacred Geometries: The Dynamics of ‘Islamic’ Ornament in Jewish and Coptic Old Cairo,” in Sacred Precincts: non-Muslim Religious Sites in Islamic Territories, edited by Mohammad Gharipour (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 158–77.

Peter Sheehan, Babylon of Egypt: The Archaeology of Old Cairo and the Origins of the City (The American University in Cairo Press, 2010).