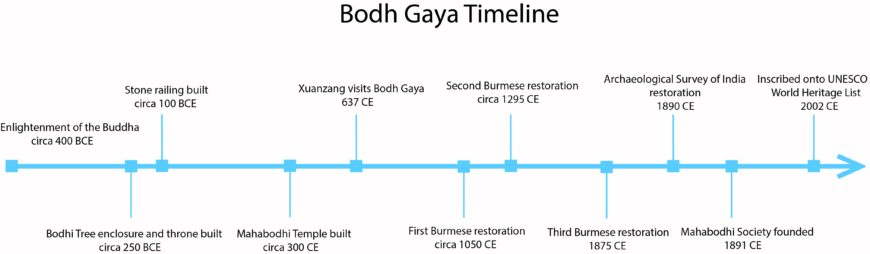

Bodhi tree with shrine, eastern gateway, Sanchi Stupa no. 1, 2nd–1st century B.C.E. (photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY 3.0)

For centuries, religion, politics, myth, and history have converged around a small town on the banks of the Phalgu River just south of the state capital Patna in India. This extraordinary place—Bodh Gaya—is understood to be the site of the enlightenment, or “great awakening” (Sanskrit, mahabodhi), of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha. It was here that Siddhartha Gautama sat in meditation under the Bodhi tree, having renounced his princely life to wander and practice asceticism. Here, he defeated temptation in the form of the demon Mara, and set a great world religion—Buddhism—into motion.

The events of the Buddha’s life are understood to have taken place sometime in the 5th century B.C.E. More than 2,500 years later, Bodh Gaya is a sprawling pilgrimage town dense with ancient, medieval, and modern shrines, monasteries, temples, and hotels. The historical and archaeological record at this sacred Buddhist center stretches back to at least the 3rd century B.C.E.

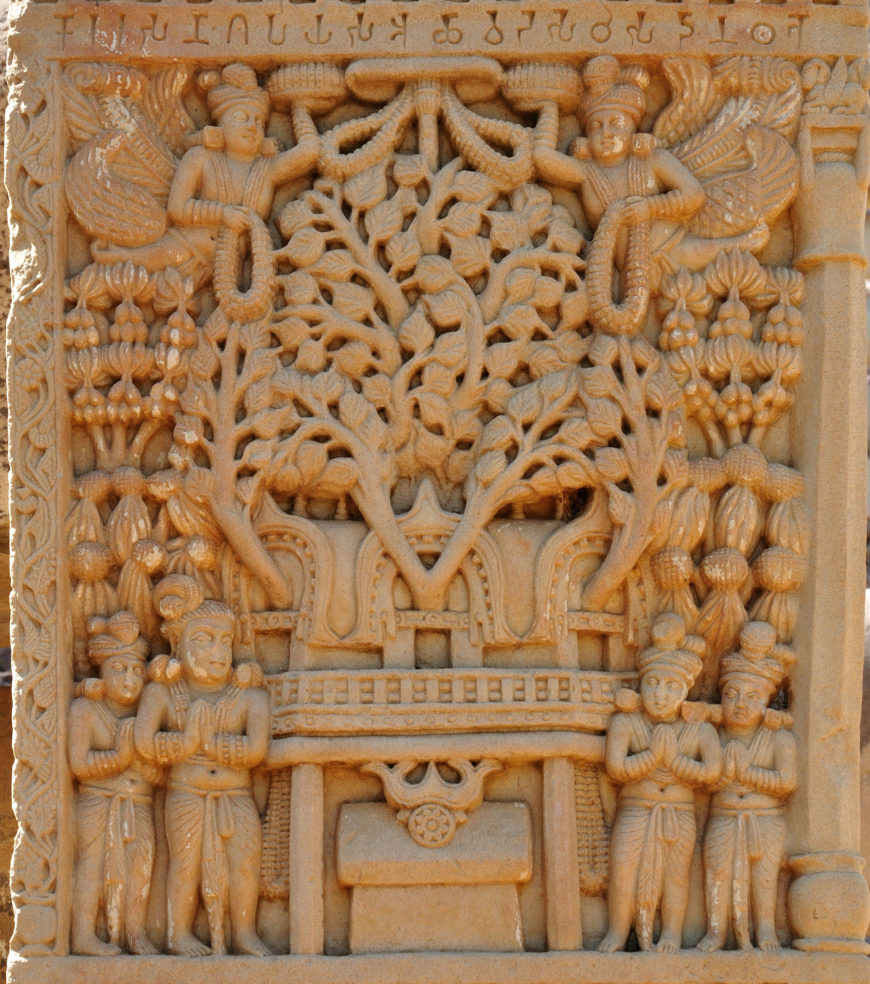

Plan of Mahabodhi Temple Complex, drawn from Cunningham, Mahabodhi, 1892, plate XVII (drawn by the author)

At the heart of ancient Bodh Gaya is the Mahabodhi Temple Complex, which is busy with shrines, monuments, and sculpted images established over more than 2,000 years. Three of the most important monuments will be discussed in this essay:

- The Bodhi tree

- The Vajrasana, or “Diamond Throne”

- The Mahabodhi Temple

Buddhist convention in front of the Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya, 2013 (photo: Triratna_Photos, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The Buddha’s Great Awakening

Siddhartha Gautama arrived at Bodh Gaya in middle age, having renounced his life as a prince on seeing the “four sights” of aging, sickness, death, and asceticism. It was the fourth sight that encouraged him to begin practicing extreme asceticism and meditation. Having done this for some time he became disillusioned with this extreme path and departed his ascetic companions wandering in north India until he arrived at the Bodhi tree (pipal tree or ficus religiosa) on the banks of the Phalgu River. [1] Taking a seat under this tree to begin a long meditation, the Buddha-to-be was seen by the servant of a local noblewoman who, thinking he was a tree spirit, presented him with a bowl of rice and milk.

Buddha calling on the earth to witness, 9th century, Bihar, India (Cleveland Museum of Art)

With this nourishment he continued to meditate under this tree and saw off the attacks of the demon Mara; who had sent both his demonic armies and daughters to distract the meditating Siddhartha Gautama. Finally, on that very night, the Buddha attained enlightenment. At that moment the Buddha was asked to provide a witness to this miraculous feat; and so the Buddha touched the earth with the fingers of his right hand, calling the Earth Goddess to witness. Buddhist traditions diverge on some of this account but this moment and the place at which it occurred, under the Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya, is significant to all Buddhist traditions.

The Bodhi Tree today at Bodh Gaya

The Bodhi Tree

As the place where the Buddha attained enlightenment, Bodh Gaya appears to have become a significant place for Buddhists soon after the death of the Buddha and the formation of the Buddhist community of monks and nuns (Sanskrit, sangha) and lay people. Very little is known, however, about the earliest structures at Bodh Gaya, and centuries of addition and alteration make it difficult to imagine how this site appeared at any particular moment in the past.

From depictions of Bodh Gaya in art dating from the 2nd century B.C.E and early narrative accounts it can be surmised that devotion at this site initially focused on the Bodhi tree itself. It is likely that this tree was surrounded by a wooden enclosure-shrine (Sanskrit, bodhi-ghara) by the 3rd century B.C.E., if not before.

Bodhi tree inside stone railing (photo manbartlett, CC BY 2.0)

According to one early narrative, the enclosure around the Bodhi tree provided a platform from which the famous early Indian King Ashoka Maurya anointed the sacred Bodhi tree with milk. [2] The stone railings enclosing a descendent of this tree at Bodh Gaya today likely date to the 1st century B.C.E., and these reveal that this wooden shrine was later replaced by a stone structure .

The Diamond Throne

A few centuries after the Buddha, a stone platform or throne was established under the Bodhi tree to mark the spot where the Buddha sat in meditation and acts as a second focus of devotion there. In some Buddhist traditions Bodh Gaya itself is referred to simply as the “Diamond Throne” (Sanskrit, vajrasana), indicating the significance of this throne to the identity of this sacred site. Some of this throne remains in-situ, though it has been moved around the site at various times in the past.

Goose and palmette motif. Diamond throne at excavation (Alexander Cunningham, Mahabodhi, 1892, Pl. XIII)

The distinctive goose and palmette motif appearing in relief on the upper register of this polished sandstone slab allows art historians to date it to the time of the Mauryan dynasty (4th to 2nd century B.C.E.), and possibly even to the time of Ashoka Maurya.

Diamond Throne of Ashoka at Bodh Gaya (photo: Christopher J. Fynn, CC BY-SA 3.0)

This throne has been moved around, restored, and altered many times in the past and is located today at the rear of the Mahabodhi Temple. The squat, atlas-like figures depicted in relief below the uppermost Mauryan throne likely date to the time of the Gupta dynasty (4th–6th century C.E.), if not a century or so earlier.

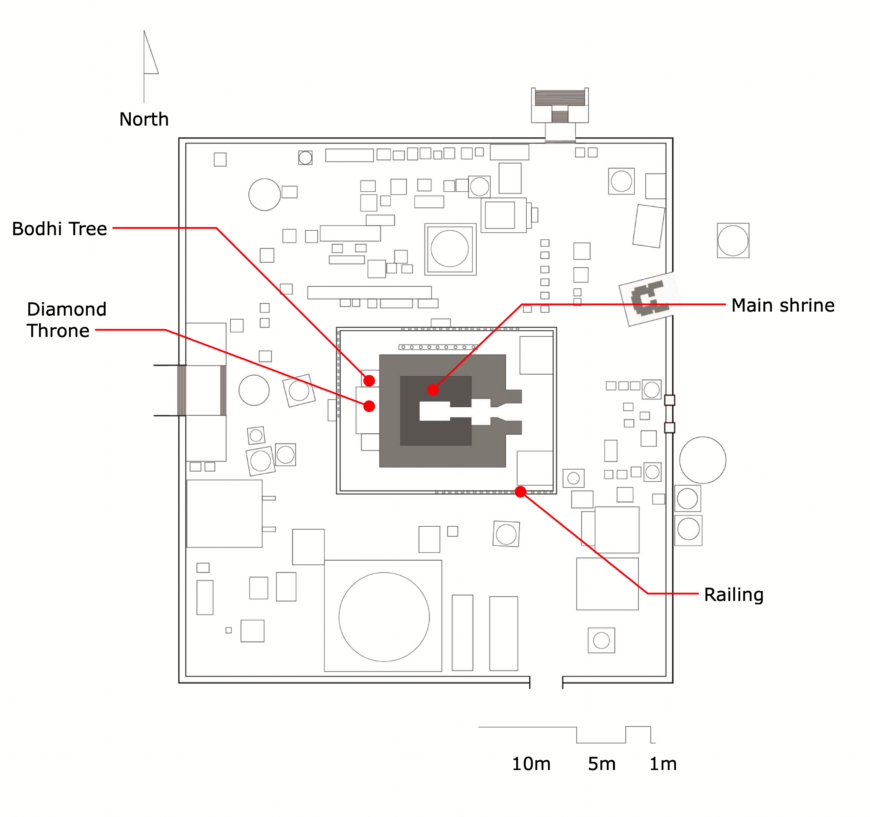

Bharhut relief with Diamond throne and Mahabodhi Temple around the Boddhi Tree (from Sir Alexander Cunningham, Mahâbodhi, or the great Buddhist temple under the Bodhi tree at Buddha-Gaya, 1892)

The combined image of this throne and the Bodhi tree was a popular image in early Buddhist art, which appears to have eschewed the depiction of the Buddha himself. The empty throne under the tree often acted as a sign for both the absent presence of the Buddha and for Bodh Gaya as a sacred site. The throne and the tree has remained an important sign for the Buddha and the moment of enlightenment throughout the history of Buddhist art, as can be seen in the early relief of the Bodhi tree with a shrine (at the top of this page) and in the common image of the Buddha calling on the earth to witness.

Mahabodhi Temple today, Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India (photo: manbartlett, CC BY 2.0)

The Mahabodhi Temple

The accounts of Chinese pilgrims who visited Bodh Gaya from at least the 5th century C.E. onwards give historians an idea of the next phase of construction at Bodh Gaya. Their accounts reveal that at some point in the early centuries of the Common Era the Bodhi tree and the Diamond Throne were partly superseded—or added to—by a towering temple housing a sculpted image of the Buddha.

Some art historians argue that a terracotta plaque from the 3rd century C.E. found near Patna represents the earliest Mahabodhi Temple. Whether or not this is the case, it is likely that the first iteration of the Mahabodhi Temple looked something like the one depicted: a tall straight-sided structure comprised of multiple layers of small arched “cow’s eye” windows (gavaksha) tapering slightly at the pinnacle and surmounted by parasols and banners marking the presence of the Buddha and surrounded by a railing on all sides. The temple depicted in this plaque also houses an image of the Buddha.

Buddha calling on the earth to witness, 9th century, Bihar, India (Cleveland Museum of Art)

This broadly agrees with the description of Mahabodhi Temple given by the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang who visited Bodh Gaya centuries later, at the end of the 7th century C.E. He describes a temple that is “160 or 170 feet high . . . [with] niches in the different storeys [holding] golden figures. The four sides of the building are covered with wonderful ornamental work.” [4]

According to Xuanzang and other pilgrims accounts, the Mahabodhi Temple housed a sculpted image of the Buddha in a seated position with his right hand touching the earth, recalling the moment of enlightenment when the Buddha “called the Earth to witness.” This image became an increasingly popular theme in Buddhist art around the 7th century C.E., as we see in the Buddha calling the earth to witness.

Model of the Mahabodhi Temple (front and side), 11th–12th century, Bihar, India (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In subsequent centuries this “earth touching” Buddha image was combined with representations of the Mahabodhi Temple itself. These “pilgrim plaques” and miniature “models” of the Mahabodhi Temple give historians an idea of what this temple looked like at this time. Depictions of the Mahabodhi Temple also suggest the increasing importance of the temple housing the Buddha image in its own right as a sign for Bodh Gaya and the events there, although the Diamond Throne and the Bodhi tree continue to be depicted alongside them.

It is around this time too that inscriptions begin to refer to the Mahabodhi Temple as the “vajrasana-gandhakuti,” literally the “perfume chamber (i.e. temple) with the Diamond Throne.” These inscriptions, the depictions of the Mahabodhi Temple in art, and other evidence for royal and foreign-sponsored programs of restoration suggest an important shift from tree shrine to the building of temples, shrines, and monasteries at Bodh Gaya over the course of the 1st millennium C.E. [3]

Mahabodhi Temple, Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India (photo: Santosh Kumar, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Mahabodhi Temple today

The Mahabodhi Temple as it appears today is mostly the product of restorations undertaken in the late 19th century: first by a Burmese mission and then overseen by the recently established Archaeological Survey of India (see the timeline above). The towering brick, stucco and concrete temple seen at Bodh Gaya today comprises a large primary straight-sided spire (Sanskrit, shikhara), rising out of a central image chamber (Sanskrit, garbha-griha). Four smaller spires sit on the corner of the main chamber and each of these is, like the primary spire, surmounted by the form of a Buddhist relic mound (Sanskrit, stupa). The surface of the temple is studded with receding levels of Buddha images set into niches alternating with circular “cow’s eye windows,” not unlike the accounts of Chinese pilgrims and early depictions of this building in art.

The late 19th-century restoration of the Mahabodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gaya made significant alterations to the site, however. Although these were based on architectural remains and models such as that shown in the model of the temple, pre-restoration paintings and photographs reveal how much was invented, such as the gateway pavilion on the second storey, the four corner spires, and much of the surface ornament. This period of restoration and partial excavation of the complex also brought to light the many small “votive” (pertaining to a wish) shrines and images which had steadily built up around the temple over centuries.

Mahabodhi Phaya, Pagan, Myanmar (photo: David-Stanley, CC BY 2.0)

Many Mahabodhis: replication of Bodh Gaya

An important feature of Bodh Gaya and the Mahabodhi Temple Complex is its replication across Asia. What might be called “replica” Mahabodhi temples were built across Asia from the 13th century onwards: the Mahabodhi Phaya in Myanmar, Wat Chet Yot in Thailand, Wuta Si in China, and the Mahabuddha Temple in Nepal are important examples.

Model of the Mahabodhi Temple, 11th–12th century, Bihar, India (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Each of these structures imitate the form of the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya, though they vary in style, building technology, and materials. Each temple works with similar assumptions of the Mahabodhi Temple form, being mostly organized around four towers surrounding a central larger tower. It is likely that some of these replicas were built from the recollections of pilgrims, if not on even small portable artworks and “models” carried away from Bodh Gaya such as that shown in model of the temple at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. These other Mahabodhi Temples may have been constructed because access to north Indian Buddhist sites was not easy for Buddhist pilgrims, especially at a time when monastic Buddhism had declined in the region. How and why these many Mahabodhi Temple were built, however, remains unclear; likely each of these buildings was built for a specific purpose in each context but all of them can be understood to, in a sense, transfer the Buddhist “holy land” abroad.

This replication of Bodh Gaya in the medieval and early modern period in Asia finds an earlier precedent in the account given in the Sri Lankan chronicle (mahavamsa) which records how a branch of the Bodhi tree was brought to Sri Lanka and planted in the city of Anuradhapura in the time of King Ashoka, where its descendant grows to this day. [5]

Bodh Gaya Today

International interest in Bodh Gaya increased from the 1880s onwards, particularly after the Archaeological Survey of India restored and landscaped much of the Mahabodhi Temple Complex. This ushered in a new phase of patronage, construction, and contention at the site. Over the course of the 20th century, international Buddhist communities and associations began to establish temples, monasteries, and guest houses in the town. Today at least forty different Buddhist organizations are represented in Bodh Gaya—a town with a mostly Hindu and Muslim population.

Many of the sculptures found at Bodh Gaya—including those used in worship today—date to the time of the Pala dynasty (8th–12th century C.E.) and depict both Buddhist and non-Buddhist deities. And it is likely that Bodh Gaya held significance within a network of sacred and pilgrimage sites in the region, both for Buddhists and other religious communities. It is also important to note that Bodh Gaya neighbors the major Hindu pilgrimage town of Gaya: an ancient sacred center associated with ancestor rites (Sanskrit, shraddha).

Indeed a major Shaiva (pertaining to the Hindu god Shiva) monastery was established just north of the Mahabodhi Temple Complex in the 18th century C.E., and this community of renunciates (people who renounces earthly pleasures and lives as ascetics) assumed administrative control of the complex around this time. Until recently the Shaiva Mahant (head of monastery) took up residence in a small building just opposite the Mahabodhi Temple and worshipped images of Buddhist deities installed there as forms of Hindu gods.

Relationships at Bodh Gaya became strained in the late 19th and early 20th century, and the ownership and authority of the Mahabodhi Temple in particular became contested. It was initially in order to “reclaim Bodh Gaya for Buddhists” that the Sri Lankan-born Buddhist revivalist Anagarika Dharmapala established the Maha Bodhi Society in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in 1891. The Maha Bodhi Society campaigned to overturn Shaiva Hindu authority at the Mahabodhi Complex by appealing to first British colonial authorities and then to the independent Republic of India after 1947. After a lengthy legal battle, the question of ownership of the Mahabodhi Temple Complex was partially resolved in 1949 after the Indian Government assumed control of the site for the State of Bihar and established the Bodh Gaya Temple Management Committee (BTMC), which was composed of both Hindu and Buddhist members.

With the Mahabodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gaya added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2002, responsibility for this place shifted once again. While its new status as “World Heritage” brought international attention and renown to Bodh Gaya, it has also caused some concern that the spiritual and devotional character of Bodh Gaya will be altered and even that Bodh Gaya will be “museumized”—its built remains being preserved at the expense of the range of sacred, devotional, and architectural practices that have characterized the place for more than 2,000 years.

The Timeless Seat of the Buddha

Bodh Gaya has a long and complex history. Over millennia it has been reconstructed and reimagined; it is steeped in significance and stories. The variety of perceptions of this place across the Buddhist world and more locally are reflected in the site’s physical history: the densely packed amalgam of structures, shrines, and sculptures that span the breadth of two millennia. Each addition, whether physical or conceptual, has built upon an earlier layer, changing Bodh Gaya without entirely erasing that which came before. The Bodhi tree, the railing, and the Diamond Throne remain at Bodh Gaya alongside the towering temple, the Buddha image, the Shaiva Mahant’s residence and — a hotel and a museum.

Notes

[1] For the life of the Buddha see, Patrick Olivelle, Life of the Buddha, Clay Sanskrit Library; 33 (New York University Press, 2008); and The Play in Full, translated by the Dharmachakra Translation Committee under the patronage and supervision of 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha, 2013.

[2] See John S. Strong, The Legend of King Asoka. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), pp. 250-266.

[3] See Geri H. Malandra “The Mahabodhi Temple” in Janice Leoshko, Bodhgaya, the Site of Enlightenment. (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1988), pp. 9–28.

[4] See Samuel Beal trans. Si-yu-ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World (London, 1884; reprinted Delhi, 1981), 118–119.

[5] See Vidya Dehejia, “Bodh Gaya and Sri Lanka” in Janice Leoshko, Bodhgaya, the Site of Enlightenment. (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1988), pp. 89–100.

Additional resources

Archaeological Survey of India

Archaeological Survey of India on Google Arts and Culture

David Geary, Matthew R. Sayers and Abhishek Singh Amar, Cross-disciplinary Perspectives on a Contested Buddhist Site (Routledge, 2012).

Janice Leoshko, Bodhgaya, the Site of Enlightenment (Marg Publications, 1988).

Prudence R. Myer, “The Great Temple at Bodh-Gaya,” The Art Bulletin vol. 40 (1958).