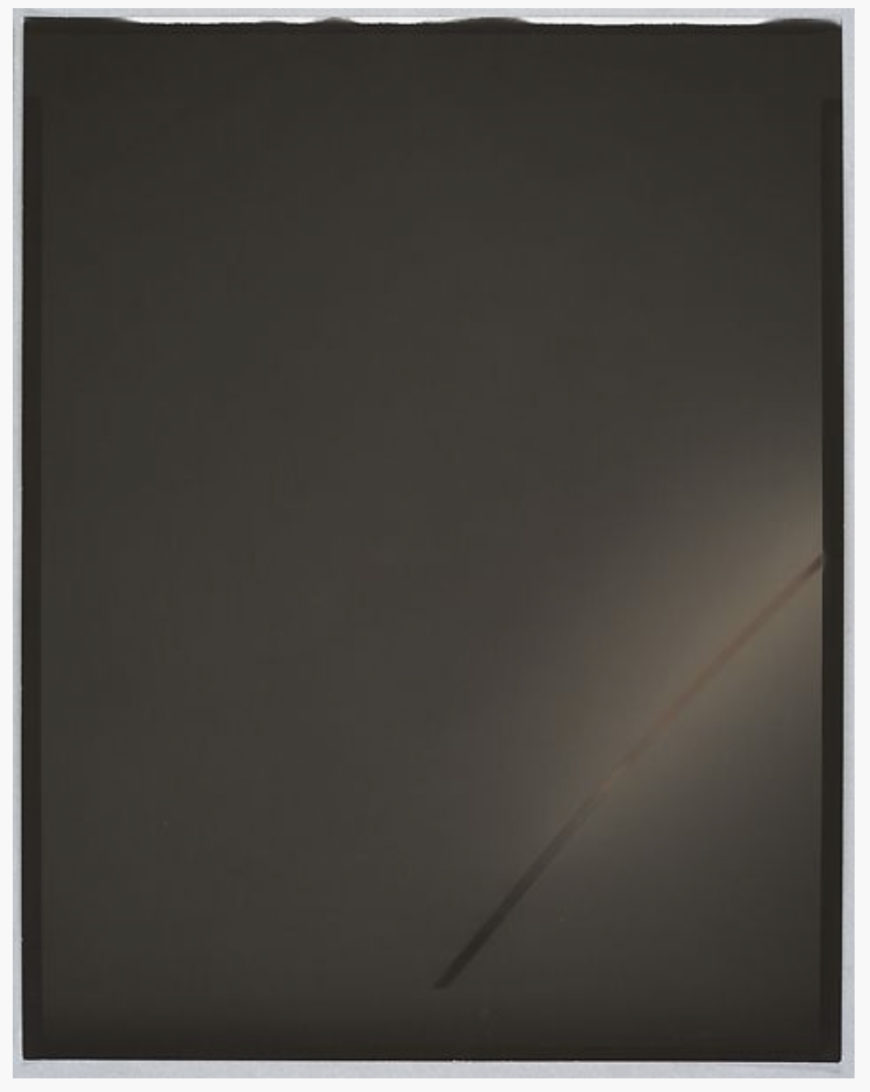

Chris McCaw, Sunburned, GSP #166, Mohave/Winter Solstice, 2007, gelatin silver prints, each print: 34.7 x 26.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) © Chris McCaw

In 1839, at the very beginning of photography’s history, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre wrote that his invention (the daguerreotype) “gives her [Nature] the power to reproduce herself.” [1] Chris McCaw’s series, Sunburn, takes this maxim as a defining rule. In his quadriptych made of four black-and-white gelatin-silver photographic prints, Sunburn GSP #166 (Mohave/Winter Solstice Day), he traced the arc of the Sun over four hours as it moved across the sky in the Mojave Desert during the Winter solstice (when the days are their shortest) in 2007. In McCaw’s work we don’t so much see the arc of the Sun, but instead the direct record of Sunlight’s energy which has left a scorched line on the paper negative, running across the four photographic prints.

Sorcery and solarization

A shot of Chris McCaw at work on a beach in Santa Monica in the Los Angeles Times‘s Arts & Music section, accompanying an article on the photographer’s “Sunburns” exhibition (photo: Daniel Miller / Duncan Miller Gallery)

In order to produce his photographs, McCaw has developed unique, homemade large-format cameras. His cameras are built to house custom film holders that will carry the paper (not film) that we see in his finished work (each roughly 11 x 14 inches, in this example). Mounted on dollies, McCaw’s cameras appear as industrial relics when compared to microscopic contemporary digital cameras. To seize the Sun’s light, McCaw’s cameras use military-grade lenses, often from aerial-reconnaissance cameras used during World War II and the Korean War, and that have long focal lengths (of around 600 millimeters) that can bring distant objects closer, while also narrowing the field of view. His use of aerial reconnaissance lenses enables the Sun to appear larger on paper than it would otherwise. Furthermore, what were once used to create clear images of the ground from above here play a reversed role in McCaw’s hands, and are aimed at the brightest object in the sky. In his photographs, the Sun imprints itself so strongly on the photographic paper that it obliterates its own image.

McCaw, like a photographic sorcerer, stated that the process for making the Sunburn series was developed by accident:

In 2003, in Utah, I just happened to have pointed the camera East, with the aperture wide open, to get as many stars in as possible, focus to infinity, and, um … I woke up around nine or ten the next morning, and I just woke up going, welp, didn’t get that shot! [I] didn’t really think too much about it, until I went to go close the shutter, and the smell of smoke was kind of coming out. I didn’t even think too much of that, and closed the shutter, put the dark slide back in, and took photographs the rest of the day. That evening I was changing film and this one sheet had a tear in it—how did I do that?—and then the lightbulb: oh, that’s right, the Sun. [2]

The image that resulted from McCaw’s accident was a solarized negative—an image in which the grayscale tones are reversed, and light areas appear dark (and vice-versa).

Chris McCaw, Sunburned, GSP #166, Mohave/Winter Solstice (detail), 2007, gelatin silver prints, each print: 34.7 x 26.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) © Chris McCaw

McCaw’s choice of gelatin-silver, black-and-white photographic paper contributes to the representation of delicate details, glimmering highlights, and atmospheric shadows. Though subtle, McCaw’s images such as Sunburn GSP #166 are nothing short of dramatic, seeming to harness elemental aspects of his medium as well as our nearest star. The crisp edges of the Sun-burned track not only reveal the understated beauty of his analog photographic materials, but the work also records a particular place and time. It reminds us of our relative scale in the solar system. As McCaw stated in 2012: “I’ve become attuned to the reality that we’re all running around on a spinning marble orbiting a fiery ball.” [3]

Index

All photographs are inherently convey a trace resulting from physical contact with a now-absent object. Another way to say this is that they are indexical. For example, a footprint, a shadow, and a burnt ember are indexical signs, because they result from a physical relationship with something no longer present. Likewise, the imprinting of light from the Sun on a light-sensitive surface is another indexical transaction, as the Sun’s light, concentrated by the lens, burned the paper. Sunburn GSP #166 also indexes the Earth’s rotation, as well as the time it takes for our “star” to rise and fall over a horizon.

McCaw’s gesture also expresses the pictorial possibilities of abstraction. He violates the purity of the empty canvas (or allows the Sun to do so), a desecration we understand not as transgression, but as a means to revel in the sublime wonder about our cosmic home.

Notes:

[1] Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, “Daquerreotype,” in Classic Essays on Photography. ed. Alan Trachtenberg (New Haven: Leete’s Island Books, 1980), p. 13.

[2] The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. “Chris McCaw Discusses his Photograph, Sunburned.” (Sept. 28, 2011), minute 4:21.

[3] McCaw, Chris, “Notes on Watching Shadows Move,” in McCaw, Katherine Ware, and Allie Haeusslein, Chris McCaw: Sunburn (Richmond: Candela Books, 2012), p. 86.

Additional resources

Daguerre, Louis-Jacques-Mandé. “Daguerreotype,” Classic Essays on Photography, ed. Alan Trachtenberg (New Haven: Leete’s Island Books, 1980). 11-13.

George, Lynell. “Chris McCaw’s Scorched Photography,” Los Angeles Times (May 25, 2008). Accessed Feb. 26, 2022:

Heckert, Virginia, Marc Harnly, and Sarah Freeman. Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography. (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015).

Johnson, Ken. “Chris McCaw: ‘Marking Time.’” New York Times (Dec. 27, 2012). C30.

McCaw, Chris. “About Sunburn.” Accessed Feb. 26, 2022

McCaw, Chris, Katherine Ware, and Allie Haeusslein. Chris McCaw: Sunburn (Richmond: Candela Books, 2012).

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. “Chris McCaw Discusses his Photograph, Sunburned.” (Sept. 28, 2011). 4:21.