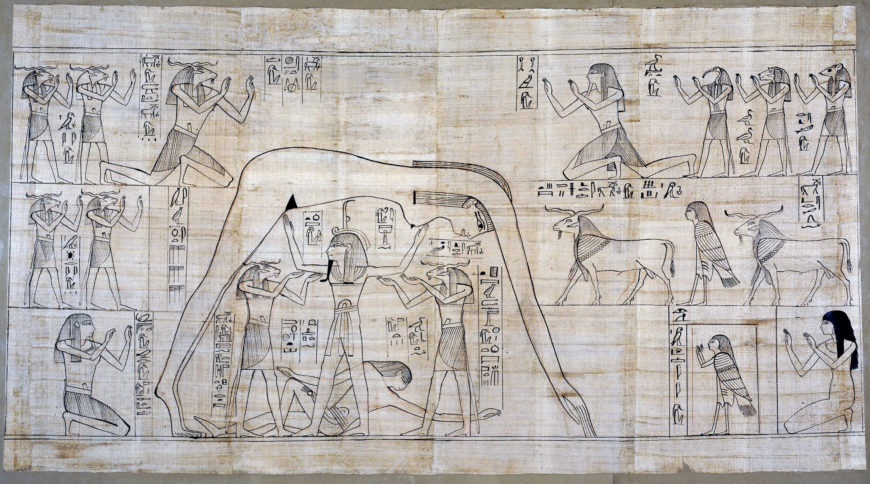

Full page black line vignette of the deities Geb, Nut, and Shu. Geb, god of the earth, stretches out below the sky-goddess Nut, who arches overhead. They are separated by the god of air, Shu, who is supported in this task. The deceased kneels to the lower right, accompanied by her ba-spirit and surrounded by groups of gods. The Greenfield Papyrus, c. 950–930 B.C.E., 21st–22nd dynasty, papyrus, excavated at First Cache, Upper Egypt, Deir el-Bahri (the Book of the Dead of Nesitanebtashru) (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Lord of Chaos, the god Seth was associated with a distinctive and unidentified animal with squared-off ears and an elongated, down-curved snout, Karnak, Egypt (Open Air Museum, Karnak; photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Egypt’s mythic world, rich with creative imagery, was deeply informed by the natural world that surrounded them. The divine landscape and the stories about the beings that inhabited it continued to evolve through Egyptian history. Over time, these myths wove an elaborate tapestry of meaning and significance, often presenting layered, seemingly contradictory viewpoints that existed simultaneously without apparent conflict.

Ourobos (detail), a shrine from the tomb of Tutankhamun, 18th dynasty, New Kingdom of Egypt (Egyptian Museum, Cairo; photo: Djehouty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Similarly, the concept of time in ancient Egypt was rather fluid; it was believed to move at different rates for certain beings and regions of the cosmos and was viewed as simultaneously linear and cyclical. Obviously, individual Egyptians experienced linear time—living their lives from birth to death—but they were also intimate with cyclical time, as evidenced in nature by the solar cycles, annual floods, and repeating astronomical patterns. They believed that an ongoing cycle of decay, death, and rebirth was what provided for the eternal consistency of the stable universe and allowed it to flourish. Fittingly, the ouroboros—the image of a snake eating its own tail and potent symbol of regeneration—originated in Egypt.

The prehistoric peoples of the Nile region, like many other early populations, revered powers of the natural world, both animate and inanimate. While some deities, like the sun god Ra, were linked with inanimate natural phenomena, most of the first clear examples of divinities were connected to animals. Falcon gods and cattle goddesses were among the earliest and may well have developed in the context of Neolithic cattle herding.

The enigmatic scenes on this monumental macehead have been much debated. They could represent the king’s heb-sed festival, divine rituals, or a royal wedding, among other possibilities. In this view, there are divine standards being carried in the top register, while the lower register shows cattle, goats, and a kneeling human with numbers under them indicating how many were captured or being presented. Narmer Macehead, Early Dynastic Period, c. 31st century B.C.E., found in Hierakonopolis (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

Already in the Early Dynastic period (c. 3100–2686 B.C.E.), there is significant evidence for the existence of many deities that were represented in human, animal, or hybrid forms (usually with human bodies and animal heads). Cult objects (statues of gods) in their local shrines shown being revered by the king were depicted on objects found in royal tombs of this period and may record actual visits by the ruler to different parts of the country to engage with those deities. The dedication of such cult images and participation in their rituals by the king was one of the most essential royal duties. Around 3000 B.C.E. when Egypt was unified under a single ruler, these disparate local deities appear to have been organized into a pantheon with relationships created between them, and these connections may have sparked various mythic stories.

There are great challenges in the study of Egyptian mythology, not the least of which are the large gaps in our knowledge due to the whims of preservation. Our most cohesive records are texts from the later periods, which often record detailed stories that present seemingly contradictory accounts. For example, there were diverse and complementary creation myths and cosmogonies (stories about the origins of the universe) that overlap to present different aspects of their understanding of how the world and the gods came into being. In the view of the ancient Egyptians, there were seven stages to the mythical timeline of the world:

- the chaos that existed pre-creation,

- the emergence of the creator deity,

- the creation (by various means) of the world and the differentiation of beings,

- the reign of the sun god,

- direct rule by other deities,

- rule by human kings, and

- a return to the chaos of the primeval waters.

At different times and in various locations, a variety of deities were identified with the creator god who emerged from the primordial waters to initiate and differentiate the cosmos. These included Ra, Atum, Khnum, Ptah, Hathor, and Isis. These myriad versions of the process of creation were connected to and promoted by cult centers, that emphasized the role of their patron deity in the process.

The three major variations of the Egyptian creation story are commonly referred to today by the cult locations where these variations were most heavily promoted: Hermopolis (Khemnu), Heliopolis (Iunu), and Memphis (Ineb-hedj).

While they differ in the details and focus on the primacy of their own local deities, all these creation systems are also quite similar in their approach, where a chaotic, amorphous watery mass of potentiality was brought under control through the establishment of ma’at and given form through the will of a creator. Many variations on these themes appeared that fit into the basic frameworks—the emerging sun god was sometimes visualized as a falcon, a scarab beetle, or a child (among other manifestations)—but all materialized from a mound and/or primeval waters. An understanding of these overlapping creation myths, and a recognition of the fact that they existed simultaneously with no apparent conflict, hints at the complexity of the mythological world of ancient Egypt.

Creation Myths

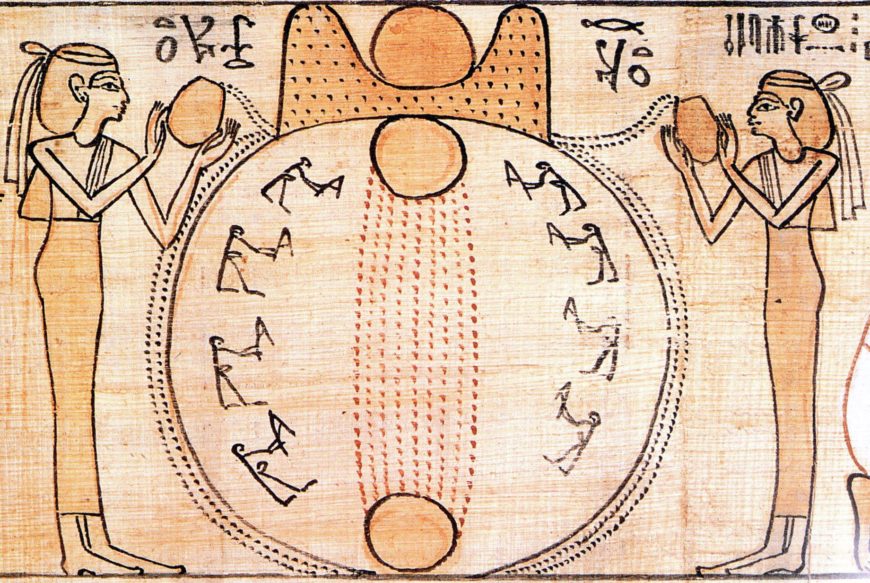

Hermopolis—cult center of the Eight

The sun rises from the mound of creation at the beginning of time. The central circle represents the mound, and the three orange circles are the sun in different stages of its rising. At the top is the “horizon” hieroglyph with the sun appearing atop it. At either side are the goddesses of the north and south, pouring out the waters that surround the mound. The eight stick figures are the gods of the Ogdoad, hoeing the soil. “The Creation of the World,” detail in the Book of the Dead of Khensumose, c. 1075–945 B.C.E., Twenty-first Dynasty (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

The Hermopolitan view (centered in Hermopolis) presented a vision of creation as a mound of earth that emerged from the primordial waters of chaos. A lotus blossom grew from this mound, opened, and revealed the newborn sun god, which brought light to the cosmos and initiated creation. Within the primeval waters were believed to be four pairs of male and female deities, known as the Ogdoad (“group of eight”) who represented elements of the pre-creation cosmos. Often represented with the heads of frogs and snakes, these chthonic beings as being associated with the primeval flood. Until the first light appeared, these beings were viewed as inert, containing the potential of creation but only “activated” when the young sun emerged from the lotus. The names of these deities, who were considered the “mothers” and “fathers” of the sun god, were masculine and feminine versions of the elements: Water (Nun & Nunet), Infinity (Heh & Hauhet), Darkness (Kek & Kauket), and Hiddenness (Amun & Amaunet).

Heliopolis —cult center of Atum

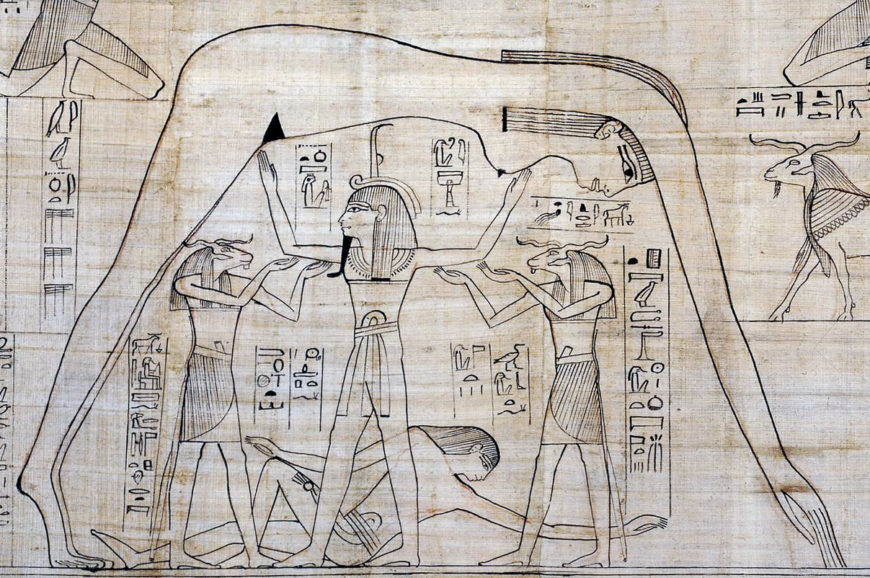

Detail of the air god Shu, assisted by other gods, holds up Nut, the sky, as Geb, the earth, lies beneath. From The Greenfield Papyrus, c. 950–930 B.C.E., 21st–22nd dynasty, papyrus, excavated at First Cache, Upper Egypt, Deir el-Bahri (the Book of the Dead of Nesitanebtashru) (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The sun god plays a primary role in the Heliopolitan creation theology. In this system, creation was enacted by a group of deities referred to as the Great Ennead. This “group of nine” consisted of the sun god, in his form as Atum, and a series of eight descendents. In this story, Atum already existed in the primordial waters (sometimes said to have been “in his egg”) and emerged alone to initiate creation. Atum was said to be “he who came into being by himself”and he then created his first two descendants, Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture) from his bodily fluids. Shu and Tefnut then created the next pair of gods, Geb (earth) and Nut (sky), providing the physical framework for the world. Geb and Nut then produced the gods Osiris and Isis, and Seth and Nephthys. These pairs, in one sense, represented the fertile Nile valley (Osiris & Isis) and the desert that surrounded it (Seth & Nephthys), completing the primary elements of the Egyptian cosmos. As all these deities were viewed as being extensions of and proceeding from the sun god, he was generally portrayed as the ruler of the gods.

Memphis—cult center of the great craftsman Ptah

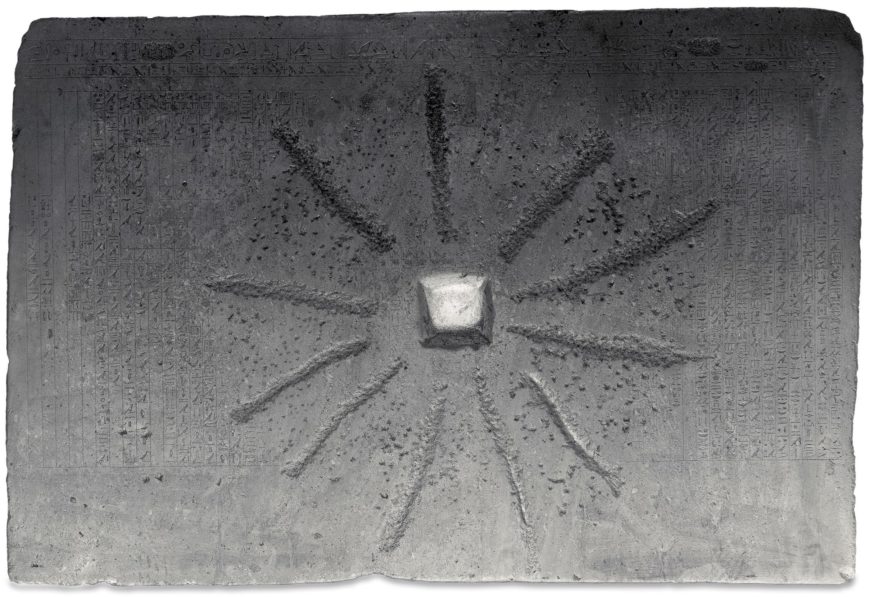

This slab was reused as a millstone, which is why it is horribly worn in that spoke pattern. If you zoom in on the image you have, you will see the vertical lines of text. The Shabako Stone, 710 B.C.E., 25th dynasty, found in Memphis, Egypt, 95 x 137 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The Memphite Theology is recorded on an important artifact now known as the Shabaka Stone. This black basalt stelae was originally set up in the ancient temple of Ptah at Memphis and preserves the only surviving copy of this religious text. According to the inscription, which is heavily damaged, the text of the stelae was copied from an ancient worm-eaten papyrus that the pharaoh Shabaka ordered to be transcribed in order to preserve it (this story, however, is debatable). The text contains references to the Heliopolitan account but then claims that the Memphite god, the chthonic Ptah, preceded the sun god and created Atum. Ptah was viewed as the “great craftsman” and the text alludes to creation being enacted through his conscious will and rational thought—the form of the earth was described as being brought about via his creative speech.

These variations on core mythic elements may have resulted from attempts to incorporate deities that emerged at various times and locations into an existing framework of creation stories.

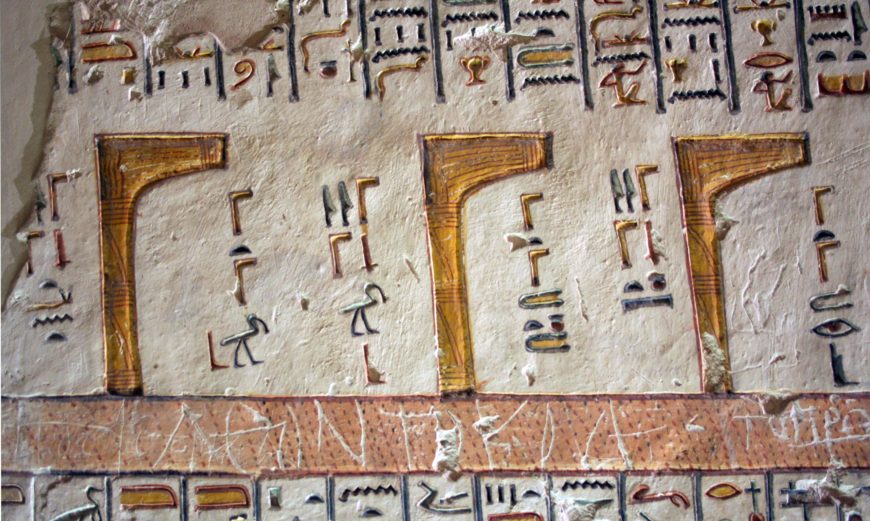

Netjer hieroglyph written as a wrapped pole with a flag on top. A row of netjer signs from the tomb of Ramses VI (KV9). Painted details show the pattern of the wrapping used on these divine symbols (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The form(s) of the gods

The Egyptian word that modern scholars translate as “god” is netjer, which is written in hieroglyphs as a wrapped pole with a flag on top—a symbol of divine presence that dates back to Predynastic times. However, it is clear that this term encompassed not only what we would consider gods, but also deified humans, other types of supernatural beings, and even chaotic monsters (like the great serpent Apophis who was the chief foe of the sun god Ra). Spirits of the deceased (akhu), demon-like dwellers of the underworld, and beings called bau, which were manifestations of the gods that served as their messengers, were also feared and revered.

The human Hunefer being led by Horus (falcon-headed) to stand before Osiris (seated), with Isis and Nephthys behind him. Judgement in the presence of Osiris, Book of the Dead, 19th Dynasty, New Kingdom, c. 1275 B.C.E., papyrus, Thebes, Egypt (British Museum)

The gods took various physical forms: anthropomorphic (human), zoomorphic (animal), hybrid (with the head of either a human or animal and the body of the opposite type), and composite (where characteristics of different deities were merged into one form). Many deities were fluid in the way they were represented and a truly fixed form for any deity was quite uncommon—sometimes, only the name clearly specifies which deity is being represented. The god Thoth, for example, was often depicted with a human body and the head of an ibis but could also be represented in fully-animal form as an ibis or as a baboon.

Capital of Hathor with a human head and bovine ears (left) and Hathor in Bovine form (right), both from the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut, Dayr al-Baḥrī, Egypt, c. 1470 B.C.E. (photos: Dr. Amy Calvert)

Few deities were shown in all three main representational modes, but there were exceptions, such as the goddess Hathor, who could be portrayed fully human, fully bovine, or as a woman with a cow head. Keep in mind that these representations were not what the gods actually looked like in the Egyptian conception. Instead, they were visualizations of the deities’ characteristics, providing physical forms that allowed for interaction with the gods.

Wall relief of The Theban Triad, Amun, Mut, and Khonsu (left to right), mortuary temple of Ramses III, Medinet Habu, Theban Necropolis, Egypt (photo: Rémih, CC BY-SA 3.0)

There were also many other types of groupings of deities, especially triads. These father-mother-child groupings, like the Theban Triad of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu, were viewed collectively in certain contexts but each still maintained their individuality. Rather different was a practice known as syncretism where different deities were merged into one body. This appears to have been an effort to acknowledge when a deity was dwelling “within” another deity when performing roles that were primarily functions of the other. Often these were combinations of similar deities or different aspects of the same god, such as Atum-Khepri, which combined the dusk and dawn manifestations of the sun god. Other examples merged deities of very different nature, such as Amun-Ra, where the “hidden one” (mentioned above) was combined with the visible power of the sun to create the “King of the Gods.”

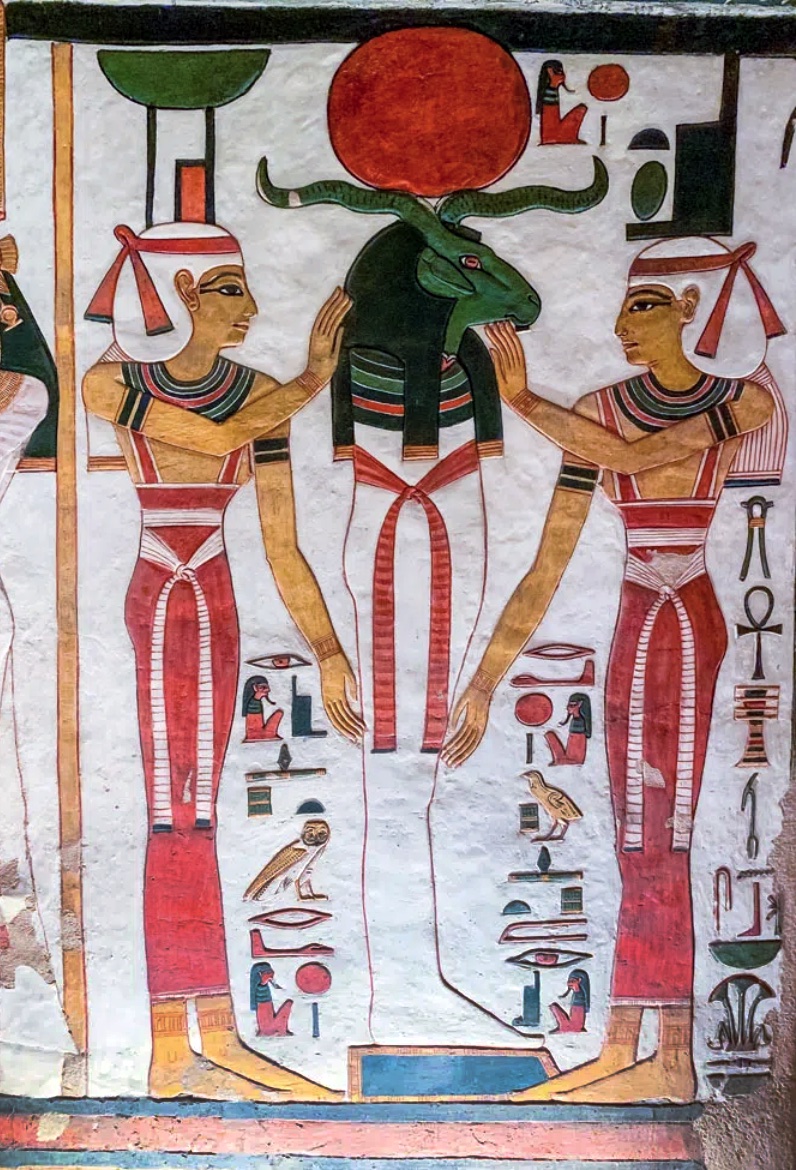

Ra and Osiris merged into one (center figure), tomb of Nefertari, 19th dynasty c 1290 1220 BCE, Middle Kingdom, West Thebes Egypt

Death, cycles, and the end of time

Egyptian deities were not static beings. Osiris, one of their most important gods, actually died (although the texts never directly say this, they do refer to him being dismembered, mummified, and buried) and then was transformed into the Lord of the Underworld. Others, like the sun god Ra, had cycles—Ra was believed to reach his zenith at midday (as Harakhti), grow old at the end of the day (as Atum), “die” at night, merging with Osiris in the depths of the netherworld to enact regeneration, and then was resurrected again with the dawn (as Khepri). In the Egyptian view, life led to death and then death re-emerged as new life; this cycle applied to humans and the gods alike, enabling them to become young again with eternal sameness.

At the end of time, the Egyptians believed that all the variety of the cosmos, including the gods, would revert to the undifferentiated condition of time before creation, with everything merging back into the primeval waters of potentiality.