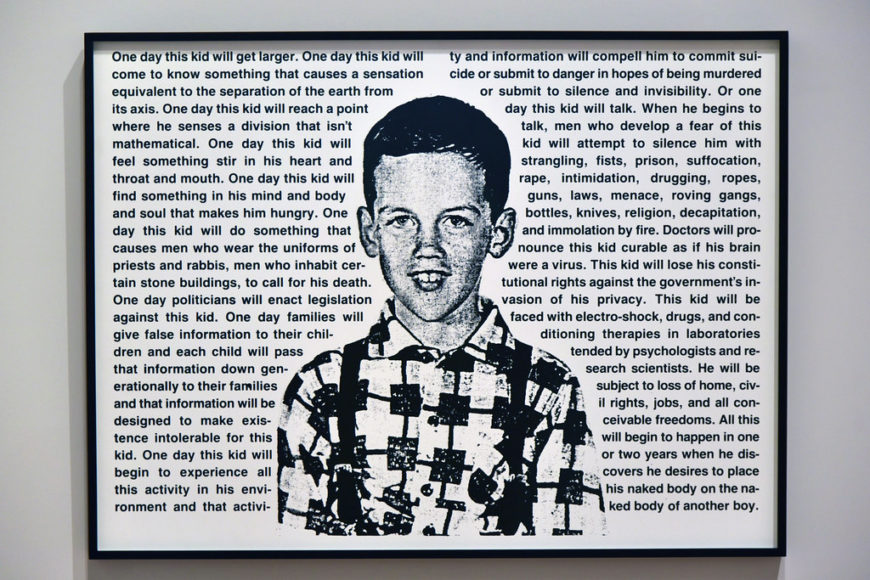

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (One Day This Kid . . .), 1990, photostat, sheet: 75.7 x 101.9 x 0.5 cm (Whitney Museum of American Art) © The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

David Wojnarowicz’s large Photostat print acts as a kind of time machine. Surrounded by text, a photograph of the artist as a young boy takes us back to a bygone, Cold War United States of the late 1950s and early 1960s when conformity was king. Boys of his generation would have been expected to work, pay taxes, marry, father children, worship, lay down his life on the battlefield if his country asked him to, and otherwise be a productive member of society. This is the future that awaits this seemingly typical white boy: skinny with long front teeth, big ears and a tidy haircut, dressed in a square-patterned shirt and frontally posed for a school photograph. In reality though, Wojnarowicz’s family was often transient and he was severely abused at home. But on the streets of New York, he would soon create a new family with other discarded young men.

Photo + text

Untitled (One Day This Kid . . .) is exemplary because it brings Wojnarowicz’s writing and image-making practices together with his political activism. His writing is celebrated for its visceral, first-person voice fueled by a sense of despair and rage at America, a country he felt was so wealthy and technologically advanced yet so vicious towards its most vulnerable inhabitants. He frequently worked with found photographs like the one included here in his many ambitious paintings. He also experimented with film, video, performance, and music. He was a member of the band, 3TK4 (3 Teens Kill 4).

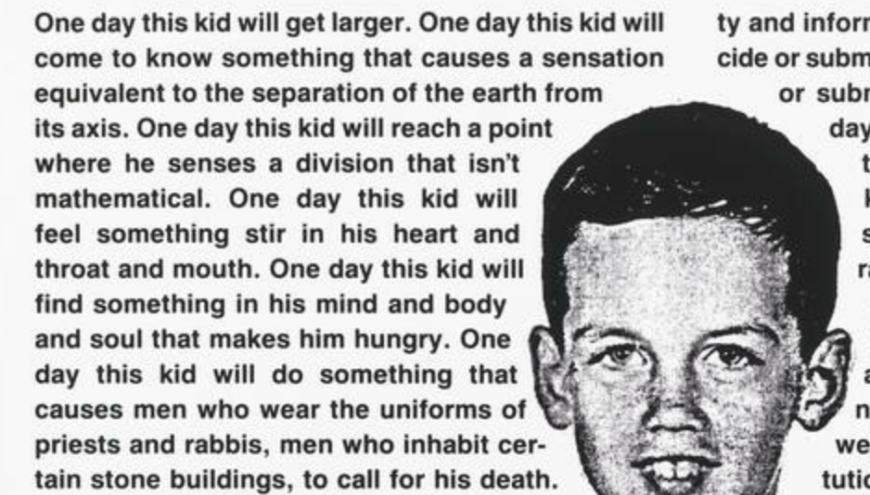

David Wojnarowicz, detail of Untitled (One Day This Kid . . .), 1990, photostat, sheet: 75.7 × 101.9 × 0.5 cm (Whitney Museum of American Art) © The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

A warning from the future

In the print, Young David is close to being visually overwhelmed by the explanatory text that captions him: he cannot escape the difficult future life that it describes, so different from the traditional norms society laid out for him. Wojnarowicz, writing thirty years later, confronts the kid in the old photo—who had no idea of the twists and turns his life would take—with his harsh fate. The text is in the future tense, and the repetition of “One day this kid . . .” or “one day . . .” creates a strong sense of inevitability. As the text builds over fifteen sentences arranged tightly in two flanking columns, we are kept in suspense as to what he has done to make him such a threat to the social order.

A litany of abuses

We first learn that as this kid grows up he will experience a “sensation equivalent to the separation of the earth from its axis,” a deep hunger. If he acts on this desire, it will cause “men who wear the uniforms of priests and rabbis, men who inhabit certain stone buildings, to call for his death.” If he is not killed, he will be driven to suicide or to “submit to silence and invisibility.” If he resists silence and speaks out, the attacks on him will only escalate, and Wojnarowicz pulls no punches as he lists methods by which violence may be enacted on him: “strangling, fists, prison, suffocation, rape, intimidation, drugging, ropes, guns, laws, menace, roving gangs, bottles, knives, religion, decapitation, and immolation by fire.” The treatment he faces from those who seek to “cure” him is just as violent, even if it claims to help: “electro-shock, drugs, and conditioning therapies in laboratories…” Finally, his civil rights will not be protected. It is only in the final punctuating sentence that Wojnarowicz clearly names the transgressive desire that doomed this kid: “All this will begin to happen in one or two years when he discovers he desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy.”

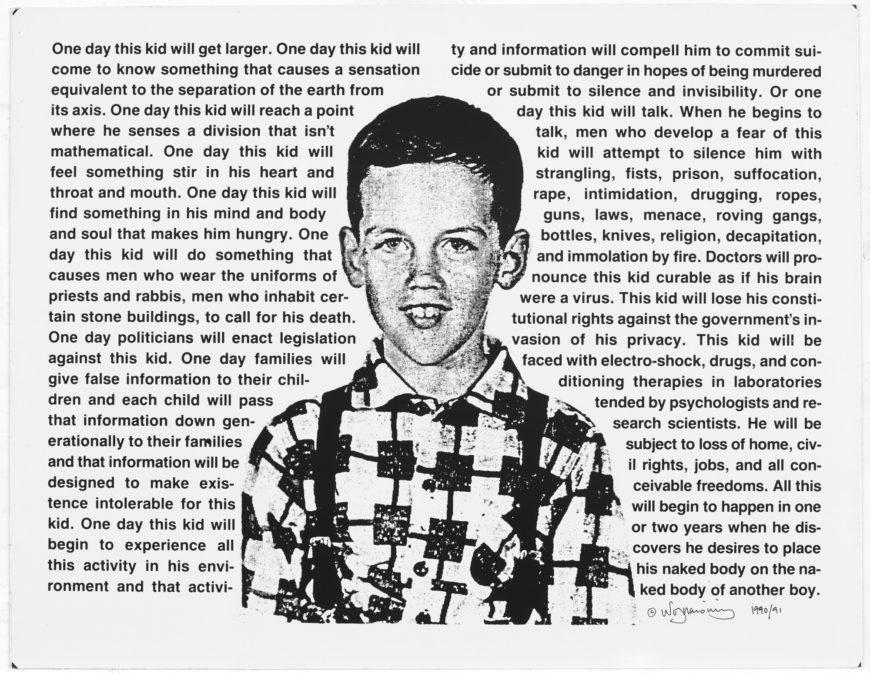

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (One Day This Kid . . .), 1990, photostat, sheet: 75.7 x 101.9 x 0.5 cm (Whitney Museum of American Art) © The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

A time machine

With this work—this time machine—Wojnarowicz catches his innocent past self before his “fall,” warning him of what is to come as punishment simply for loving people of the same sex. It deploys sentiment to illustrate how homophobia destroys children because many of us are aware of our difference in our early years and quickly understand that we may be hated for it.

As the text suggests, Wojnarowicz knew he was gay from a young age and it came to epitomize his feeling of being an outsider to American society; this feeling was further intensified when Wojnarowicz found out that he was HIV positive in 1988. This discovery galvanized his art practice and sparked his political activism, particularly as the AIDS pandemic greatly intensified societal homophobia.

When this print was created in 1990 vast numbers of gay men—including numerous gay artists in Wojnarowicz’s downtown New York circle such as his lover and mentor the photographer Peter Hujar, who passed away in 1987—were dying of AIDS, which was largely ignored by an American government that did not want to be seen as funding health initiatives intended to save the lives of homosexuals or IV drug users. Politicians and religious leaders joined forces to demonize and refuse aid to the dying. Wojnarowicz’s depiction of himself as an “every kid” is an impactful reminder of the essential humanity of People with AIDS.

A political broadside

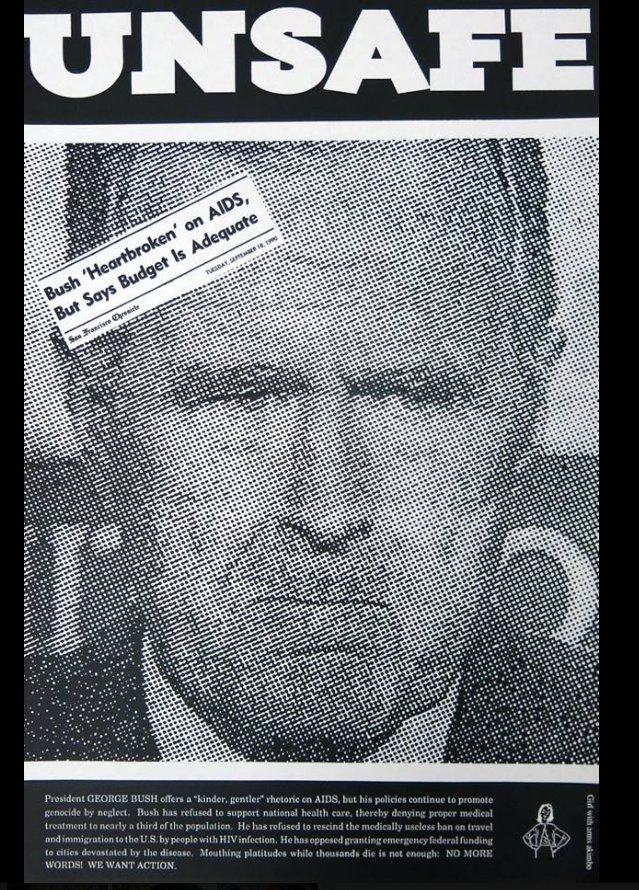

Boy/Girl With Arms Akimbo, an anonymous San Francisco-based cultural activist collective, from the “Safe/Unsafe” campaign, 1992

Wojnarowicz’s avoidance of color in favor of stark black-and-white text and image prioritizes raw, urgent communication, and indeed the print is easily reproduced and has circulated widely—and been translated—as a postcard, poster, and placard that persuades readers to fight against homophobia and AIDSphobia. AIDS activists in this period often reproduced the faces of figures like President George H.W. Bush, Senator Jesse Helms, or Cardinal O’Connor on walls or placards to shame them for their negligent response to the AIDS crisis.

Having the young Wojnarowicz’s face disseminated as a visible queer child was a potent political symbol. (It also perhaps recalled the face of Ryan White, a young Indiana boy with hemophilia who was prevented from attending school after his AIDS diagnosis by phobic parents and officials.) Transforming a school photo into a political broadside, Wojnarowicz created a kind of manifesto for queer childhood.

A call to action

The print acts as a retrospective warning to Wojnarowicz’s younger self of the injustices that await him, but the story does not end there. Salvation and love are possible and come from the community that is created by the work itself in its circulation and reception: people who identify with or empathize with the boy and the fate that awaits him. People who, after looking at the work, might commit themselves to ensuring that kids like him survive and thrive rather than suffer. In doing so it seeks to break the generational cycle of homophobia described in the text itself: “One day families will give false information to their children and each child will pass that information down generationally to their families and that information will be designed to make existence intolerable for this kid.”

Wojnarowicz understood not only his artwork but his body as a weapon, and he became increasingly involved in AIDS activism before his own death from AIDS in 1992, only two years after creating this enduring work. Some of his ashes were scattered in protest on the White House lawn during one AIDS demonstration, a powerful final act for the kid who looks out at us—his whole life ahead of him—from this print.

Additional resources

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (One Day This Kid…), 1990, Whitney Museum of American Art

Barry Blinderman, ed., David Wojnarowicz: Tongues of Flame (Illinois State University, 1990).

David Breslin and David Kiehl, David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, 2018).

Cynthia Carr, Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz (Bloomsbury, 2012).

David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (Vintage, 1991).