Grotesque, “Chamber of The Sphinx,” Domus Aurea, 65–68 C.E. (photo: Parco archeologico del Colosseo)

Hidden below the modern ground level of Rome lies the palace of the Emperor Nero (known as the Domus Aurea, the Golden House), one of the largest and most complicated Roman imperial complexes ever constructed. Roman emperors traversed its labyrinthine rooms and passageways, and centuries later the ruins were explored by renaissance artists. Today, excavations continue, and tourists can visit.

Nero (Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus), became the fifth Roman emperor in 54 C.E. at the age of sixteen. Following the model of emperors who reigned before him, Nero quickly engaged in building projects. This included public works projects, like his bath complex (the Thermae Neronis) in Rome, as well as the construction of numerous personal villas and palaces across Italy.

Decorative fresco from the Domus Transitoria on the Palatine Hill, Rome c. 60–64 C.E. (photo: dalbera, CC BY 2.0)

The Domus Transitoria

Prior to this time, the imperial residences within the city of Rome were located only on the Palatine Hill in the heart of the city overlooking the Roman Forum, the key political, ritual, and civic center of the Empire. In fact, the modern term “palace” derives from the Latin name for the hill (collis palatium). Augustus, the first emperor of Rome, and his wife Livia both had houses on the Palatine. The second emperor, Tiberius, is said to have created a new residence, the so-called Domus Tiberiana, which was also used by the third and fourth emperors, Caligula and Claudius. These palaces were not originally connected to one another.

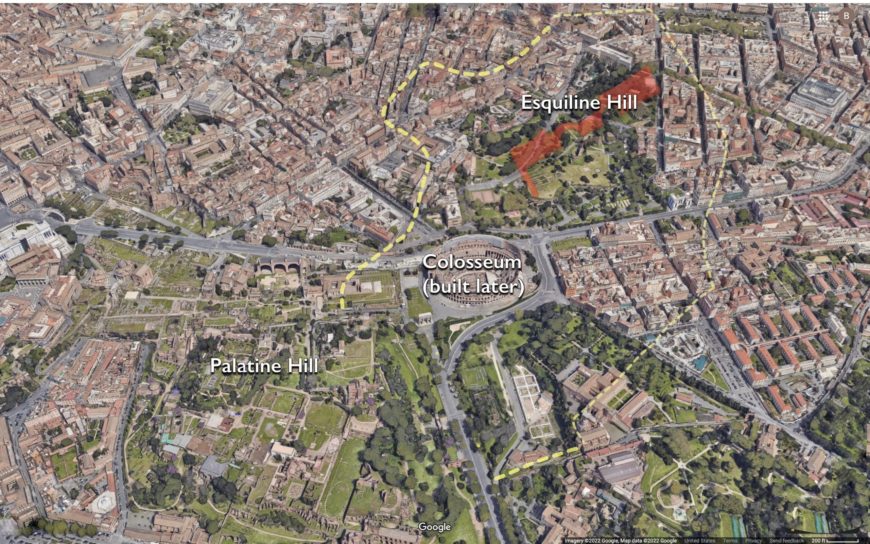

Around 60 C.E., Nero began to construct the Domus Transitoria, which means “house of transition,” a project which would connect all of the existing imperial buildings into one large, continuous structure. The goal of this project was also to extend the boundaries of the palace down into the valley just east of the Roman Forum (in Latin, the Forum Romanum) and across to the Esquiline Hill (see map below), where there were expansive and opulent imperial gardens (horti).

The great fire

Construction was well underway when, on the night of July 18th 64 C.E., a massive fire broke out in the valley of the Circus Maximus in Rome. The fire raged for approximately 10 days, destroying many areas of the city. The worst damage occurred in the center of the city where everything from homes to temples were destroyed. Most of Nero’s Domus Transitoria was lost in the blaze.

Nero helped to organize numerous relief efforts, such as providing funds for the removal of destroyed structures, coordinating food and temporary lodgings for those who were displaced, and enacting safety reforms and new fireproofing laws to attempt to prevent or limit further tragedies. Though he was staying at a seaside villa at the time of the fire (and not playing the fiddle in Rome as has often been incorrectly stated), he did capitalize on the fire and used it as an opportunity to purchase large quantities of public land in the city center.

Overhead view of stuccoed and painted vaulting, “Hall of Achilles,” Domus Aurea, 65–68 C.E. (photo: © ERCO GmbH)

Nero’s Golden Palace

With this new land under his control, Nero began construction of his golden palace, the Domus Aurea. As Nero had always hoped, the palace and its associated gardens stretched from the Palatine Hill, across the valley, and up onto the Esquiline Hill, spanning at least 50 hectares in the city center. The result was the most opulent imperial palace constructed at the time, with approximately 300 rooms, manicured gardens, a private bath complex, and even an artificial lake. In addition, there was a 120-foot colossus of the emperor in sparkling, gilded bronze in an entrance vestibule to the complex. The complex also included expansive parklands which were open to the public. This sprawling compound profoundly altered the landscape of the city center.

Location of the Esquiline wing excavations indicated in red within some of the areas of the Domus Aurea, Rome. The palace also extended onto the Palatine Hill, but the exact borders are unknown.

The most substantial archaeological evidence of the Domus Aurea today is found on the Esquiline Hill. This portion of the complex contains over one hundred rooms including a grotto, multiple dining rooms, a long cryptoporticus (covered corridor), and two large courtyards, one of which was pentagonal. The surviving remains of the Esquiline wing only provide hints of the original grandeur of the complex. The upper levels of this wing were intentionally leveled after Nero’s death, so the rooms that remain include only the lower floors and service levels. However, even these areas express the lavish design of the project and the attention to detail which was paid to all areas of the complex.

The painter Famulus and his team of assistants painted much of the vast complex in what we now call the Fourth style of Roman wall painting. Pliny the Elder wrote that the project was so consuming that Famulus was not able to work elsewhere. The majority of these frescoes had white backgrounds, though the background color used seems to have depended in part on the importance of the room. The painted compositions were often divided into different panels, sometimes enclosed by delicate floral frames, other times with thicker architectural features containing figures or smaller illusionistic panels free-floating in the central space. Some of the most opulently decorated rooms had walls clad in marble instead of fresco. Most of the ceilings were finished in stucco that was then painted or gilded.

The architects for the palace were Severus and Celer. With so much land to work with and Nero’s seemingly endless funds, they had the ability to be inventive and created a grand complex worthy of an emperor.

The Octagonal Room

One of Severus and Celer’s greatest architectural achievements and likely the most recognizable room in the Domus Aurea today is the Octagonal Room. As its modern name suggests, the room starts as an octagon at the bottom of the walls before transitioning into a hemispherical dome above. Three sides of the octagon face the exterior of the structure, overlooking the gardens in the valley below the hill, while five rooms radiate off of the other sides of the octagon.

oculus (detail), Severus and Celer, Octagon Room, Domus Aurea, Rome, 65–68 C.E. (photo: Fred Romaro, CC BY 2.0)

Light entered the space through an oculus (an opening) in the center of the dome. The architects also created gaps on the side of the hemispherical dome which were open to the sky and allowed light to stream into the neighboring rooms. Incredibly, the weight of the dome above is supported only by piers between each of the doorways. This room is a prime example of innovative Roman architecture. The use of concrete instead of stone allowed for the construction of the broad open spaces of the Octagonal Room. This structural concrete was hidden behind decorative marble or it was painted.

What remains today is only a shell of the former room. In antiquity, the walls and floor were clad in marble, and the dome plastered with stucco decorations and painted. The architectural ingenuity that made the vast open space of the Octagonal Room possible was hidden from view, so that guests were left only with the impression of a grand dining room seemingly unencumbered by columns or other supports.

Severus and Celer, Nymphaeum of Polyphemus, Domus Aurea, 65–68 C.E. (photo: © ERCO GmbH)

The Nymphaeum

Often called the Nymphaeum of Polyphemus, the Domus Aurea also contained an intimate barrel-vaulted grotto (cave-like) space, which offered a more intimate dining alternative to the Octagonal Room. The concrete walls and floor were clad in marble and the corners of the side walls and lunette (the semi-circular space at the end of the vault) were lined with seashells. Water sparkled as it fell over a staircase on the back wall and fed into a small horseshoe shaped water-basin in the center of the room. The walls contained niches for statuary.

Medallion showing a scene from The Odyssey, Nymphaeum of Polyphemus, Domus Aurea, 65–68 C.E. (photo: Jessica Mingoia, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The barrel-vaulted ceiling was covered in reddish-brown pieces of pumice, designed to look like small stalactites, inserted into stucco. This is interrupted only by five mosaic medallions, the center of which featured a scene from The Odyssey of Homer, depicting the Greek hero Odysseus serving wine to Polyphemus (the cyclops son of Poseidon in Greek mythology who lived in a cave), a theme often found in dining grottos and nymphaea. The room was quite dark, with the only light source coming from a hallway open to the sky just outside the room. The overall effect was that of a seaside cave with a waterfall and pool, providing a cool, dark retreat from the heat of the Roman summer.

Rotating dining room

The most infamous room within the Domus Aurea is Nero’s rotating dining room, which was described by Suetonius, a Roman historian and biographer:

There were dining-rooms with fretted ceilings of ivory, whose panels could turn and shower down flowers and were fitted with pipes for sprinkling the guests with perfumes. The main banquet hall was circular and constantly revolved day and night, like the heavens.Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars, Nero, 31

In 2014, the location of this famed room was found on the Palatine Hill, hidden inside a platform constructed by Nero’s successors. Though the dining room itself no longer exists, the 12-meter high tower structure made up of pillars and arches that once supported the room does. Excavations also show that the tower was powered by water-driven mechanisms and gears which allowed the room to gently rotate while diners were treated to a panoramic view of Rome. It, too, spoke to the advanced architectural and engineering skills of Severus and Celer and to Nero’s desire to create the grandest palace Rome had ever seen.

Suetonius claimed that Nero stated he at last felt like he could live like a human being in this palace.

Faces of Ancient Europe: Wonders of the Domus Aurea (Paintings from the Nero’s Golden House)

The palace destroyed

Work on the Domus Aurea was never completed. In 68 C.E., Nero elected to commit suicide rather than be condemned to death by the Roman Senate, bringing the Julio-Claudian dynasty to an end. What followed was the so-called “year of the four emperors,” some of whom lived in the Domus Aurea. However, once the dust settled and the Flavian dynasty was established, they immediately sought to distance themselves from Nero, whose megalomania had grown prior to his death.

This political strategy included destroying the Domus Aurea. Although the Palatine Hill remained the preferred site for imperial palaces, the land in the valley reverted to the public. The Flavians filled in Nero’s artificial lake and constructed the Colosseum (known at the time as the Flavian amphitheater) on top of it. The rotating dining room was razed and a retaining wall was built to enclose the remaining portions of the structure.

View of the unexcavated “Chamber Of The Sphinx,” rediscovered in 2019 (photo: Parco archeologico del Colosseo)

The remains of the palace on the Esquiline Hill were also abandoned. The upper portion of the structure was destroyed and the lower level rooms were filled in with soil. These later formed the foundation of the Emperor Trajan’s bath complex built in the early 2nd century C.E. This portion of the Domus Aurea remains the best preserved thanks to the baths above, containing a porticoed garden and more than 100 rooms, including the Nymphaeum of Polyphemus and the Octagonal Room.

From Altair4 Multimedia Archeo3D Production

Rediscovery and today

Much of the memory of the Domus Aurea faded over time. In fact, its rediscovery was completely accidental. Around 1480, a young boy fell through a hole on the Esquiline Hill into the structure and saw what he described as painted caves. Though no one yet knew that this was the Domus Aurea, it quickly garnered attention and led to many exploring the labyrinthine structure, including the artist Raphael, who is often credited with correctly identifying the structure as the remains of Nero’s golden house. Because the frescoes and stuccoed ceilings had been underground and cut off from air for so long, they were remarkably well-preserved.

Today, due to the intense humidity underground in the structure, many of the frescoes have since faded. Scientific archeological excavations did not begin in earnest until the late 20th century and the Esquiline site officially opened to visitors in 1999. Many more rooms have since been uncovered, with the latest discoveries occurring in 2019. Most of the current work on the site is focused on conservation of the archaeological remains.

The structure is under immense strain from the weight of the earth, trees, gardens, and other structures atop it. Some of the roots of the trees above have weakened the structural integrity of many of the ceilings, making it impossible to remove them without damage. One of the goals of the “Colosseum Archaeological Park,” the cultural heritage agency which now manages the structure, includes working to lessen the weight of the park above to limit the chance of collapse of the structure below.

Additional resources

Photos by the author for teaching and learning

Larry F. Ball, The Domus Aurea and the Roman Architectural Revolution (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Heinz-Jürgen Beste, and Henner von Hesberg. “Buildings of an Emperor—How Nero Transformed Rome,” in A Companion to the Neronian Age, edited by Martin T Dinter and Emma Buckley (Chichester, West Sussex, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), pp. 314–31.

Axel Boëthius, The Golden House of Nero; Some Aspects of Roman Architecture, Jerome Lectures 5 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1960).

Filippo Coarelli, Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide (University of California Press, 2007).

Frank Sear,Roman Architecture 418–21 (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1983), pp. 163–72.

Michael Squire, “Fantasies so Varied and Bizarre: The Domus Aurea, the Renaissance, and the Grotesque,” in A Companion to the Neronian Age, edited by Martin T. Dinter and Emma Buckley (Chichester, West Sussex, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), pp. 444–64.

Maria Antonietta Tomei and Rossella Rea edd., Nerone (Milan: Electa, 2011).

P. Gregory Warden, “The Domus Aurea Reconsidered,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 40, no. 4 (1981): 271–278.