Wall painting of the martyrdom of saints, Coptic period, 6th century, from a building at the Coptic town of Wadi Sarga, Egypt (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Byzantine Egypt

Egypt’s dry climate has preserved a range and abundance of architecture, sculpture, artifacts and texts unparalleled in other parts of the Byzantine world. The survival of large numbers of documents, such as contracts, petitions, tax receipts and letters, provide insight into everyday experiences of elites and non-elites, men and women.

The British Museum collection reveals aspects of the visual, social, religious, administrative, and economic lives of Egypt’s inhabitants at the time when they became predominantly Christian.

In the course of the fourth and fifth centuries C.E., Christians transformed the architectural landscape of pharaonic Egypt by building monumental churches, martyrs’ shrines, and monasteries, often converting ancient temples, shrines, and tombs for new purposes. Pilgrims from around the empire flocked to Egypt to visit sites mentioned in the Bible or associated with saints. Coptic, the Egyptian language written in a modified Greek script, flourished as a vehicle to translate the Bible and, later, to compose an original Egyptian Christian literature.

At the same time, individuals and communities continued to engage in many traditional Egyptian and Hellenistic practices. The elite dead were buried in mummiform, swathed in textiles decorated with motifs from classical mythology. Greek literature (for example, Homer and Menander) continued to be copied and read, and Greek poetry and philosophy flourished into the sixth century.

The Persian occupation (619) and, later, the Arab conquest of Egypt (642) increasingly isolated the province from the rest of the Byzantine Empire. From the ninth century Arabic began to replace Coptic and Christians increasingly converted to Islam.

Today Egypt is home to a sizable Christian population known as Copts, a term deriving from the Arabic transliteration of the Greek word for Egyptian (Aigyptios).

Polychrome tapestry band from linen garment decorated with representations of saints on red ground, Coptic period, 7th–8th century, Egypt, 90 x 12 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

The Coptic period

The term ‘Coptic period’ is a very approximate one; it may be thought of as running from the third century until around the time of the visible decline of Christianity in the ninth century. It is roughly equivalent to the Byzantine period elsewhere in the Mediterranean world.

Christianity arrived in Egypt from Judea. It probably first came into Alexandria, which was both an intellectual centre and the home of a large Jewish community. Christianity was heavily persecuted in the third century AD, but was widely accepted by the end of the fourth century. After this time, the number of monastic settlements increased. It was at this time that many ancient rock cut tombs were inhabited and adapted by Christian monks.

The term ‘Coptic’ can also be applied to the art and language of the Christian period in Egypt. The churches of the period were often highly decorated with murals showing saints and local bishops. The church buildings were also carved with floral and leafy motifs, sometimes combined with birds and animals. Similar motifs appeared on pottery of the period. The Coptic language was used for inscriptions including monastic accounts, extracts of the Bible, liturgy and psalms, and the lives of great saints and bishops.

Limestone gravestone, Coptic period, 8th century, possibly from Thebes, Egypt, 134 x 48.8 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Gravestones

Coptic gravestones vary widely in size, and this is one of the larger ones. It is decorated with the Coptic cross at the top, and with various scrolls and foliate patterns. The bird in the centre is a dove, a common image on such stelae. To the Copts the dove and the foliage were symbols of paradise. Above the dove is a short inscription, which reads, ‘Young Mary: she entered into rest on the 10th day of [the month of] Tobe’ (probably January).

Painted wooden lion’s head, Early Coptic period, 7th-10th centuries, from Qasr Ibrim, Nubia, 22.5 x 1.5 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

An architectural element from an early Christian Church

Churches and other religious buildings were highly decorated in the Coptic period. The walls were painted with pictures of bishops and saints, and architectural elements were often carved with floral and faunal motifs. Pillars and friezes were often made of stone, but this example is unusual in that it is of wood. This lion’s head, although schematized is still quite recognizable. It is carved in much higher raised relief than the leaves below, making it stand out. The curly leaves are characteristic of the floral motifs common in Coptic art. They are very similar to the acanthus leaves that appear in earlier Roman art, particularly those decorating the capitals of Corinthian columns. The basic color of the lion is reddish brown, with details picked out in yellow and black. The yellow mane can be easily identified, curving around the face from ear to ear. In both pharaonic and Coptic times, black paint was usually derived from charcoal, and yellow and brown from forms of ochre.

The lower edge of the piece of wood is heavily burnt, suggesting that the rest of the object, and perhaps the entire building, was destroyed by fire.

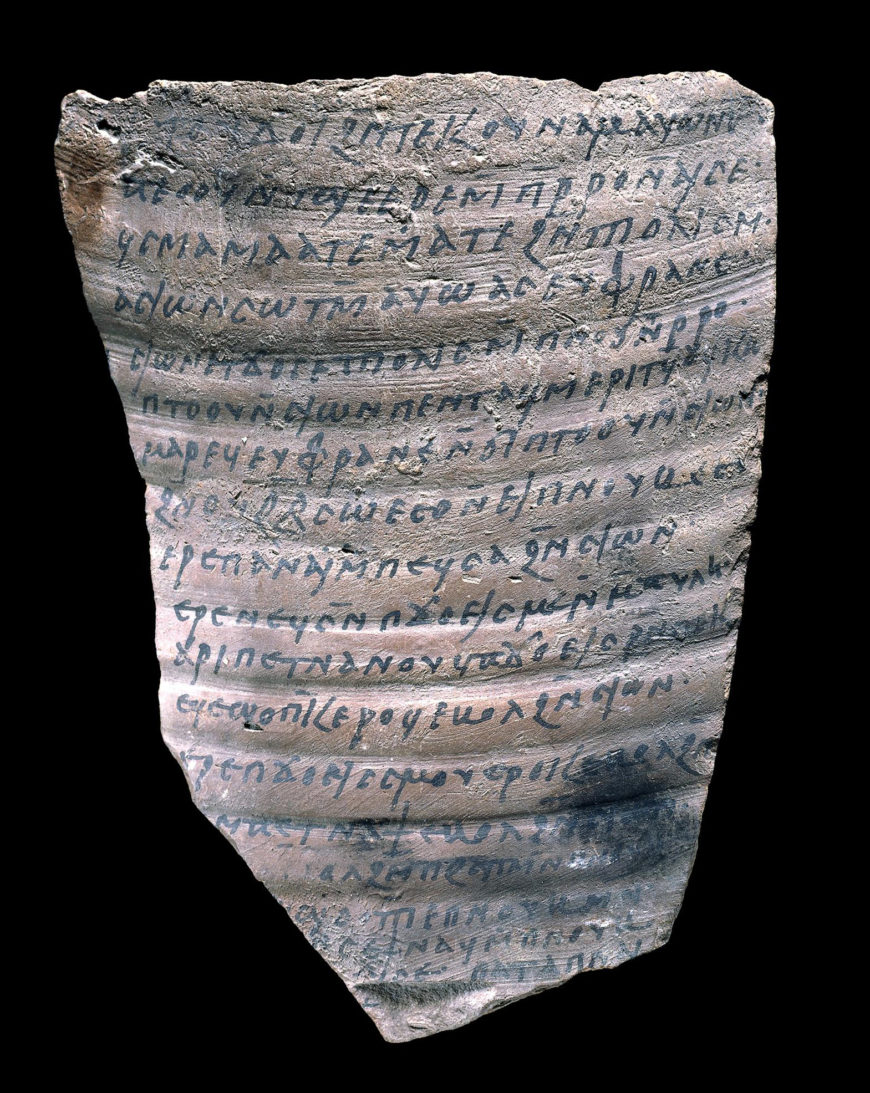

Coptic ostrakon, Early Islamic period, perhaps 7th or 8th century, possibly from Thebes, Egypt, 13.2 x 10 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Pottery sherd with the openings of several verses from the Psalms

People often used broken pieces of pottery or stone as a convenient surface for recording information or even doodling. These pieces are called ostraka. Written material of the Coptic period often had a religious theme, including extracts from the Bible, church sermons and tales of martyrdom. Ostraka were also used to record aspects of the day to day running of monasteries, such as the delivery of foodstuffs. The broken sherds are often from vessels used for the transport of products, including olive oil and wine.

The Coptic script was widely used in Egypt from the late third century until the Arab conquest in the seventh century. It developed when the use of hieroglyphic and associated handwritten scripts died out when Egypt became a Christian country. Coptic is still the official language of the Christian Church in Egypt, known as the Coptic Church. It is a direct descendent of the language written in hieroglyphs, using Greek characters to record the consonants and vowels of the ancient Egyptian language. Jean-François Champollion’s knowledge of Coptic was essential to his decipherment of the hieroglyphic script using the inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources:

H.R. Hall, Coptic and Greek texts of the Christian Period from Ostraka, Stelae, Etc. in the British Museum (London, 1905)

F.D. Friedman, Beyond the Pharaohs (Rhode Island, 1989)

S. Quirke and A.J. Spencer, The British Museum book of anc (London, The British Museum Press, 1992)