Seti I kneels before the god Amun and receives emblems of kingship conveying his authority to rule. In his left hand the king grasps a rekhyt bird, which represents the general population that is being brought under the king’s control. This elegant scene is packed with symbols of stability, life, and eternal rejuvenation, all directed at the king. Temple of Seti I at Abydos, Dynasty 19.

A hierarchy

Ancient Egyptian society was a strictly divided hierarchy. The king, chosen by the gods to rule, was at the top with layers underneath—including officials like the vizier, scribes, overseers, and regional governors (called “nomarchs”), priests, the military, and the general population of artists, tradespeople, craftspeople, agricultural workers, laborers, and enslaved people.

This hierarchical society flourished for much of ancient Egypt’s very long history largely because of the central cultural principle of ma’at—the cosmic force of order and balance that Egyptians believed governed their world. The economy was centrally organized, with a fixed wage and state distribution system. Through this process, the properly functioning state (proof of the king being in accord with ma’at) provided for the populace. The king officially owned all the land and the state received goods and services through taxation. Taxes were levied, collected, and recorded by the offices of the vizier and placed in centralized storehouses. These goods were then redistributed back to the people.

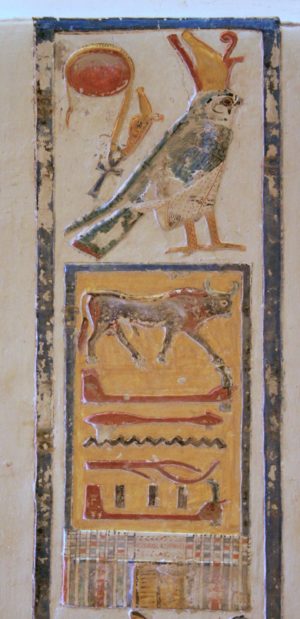

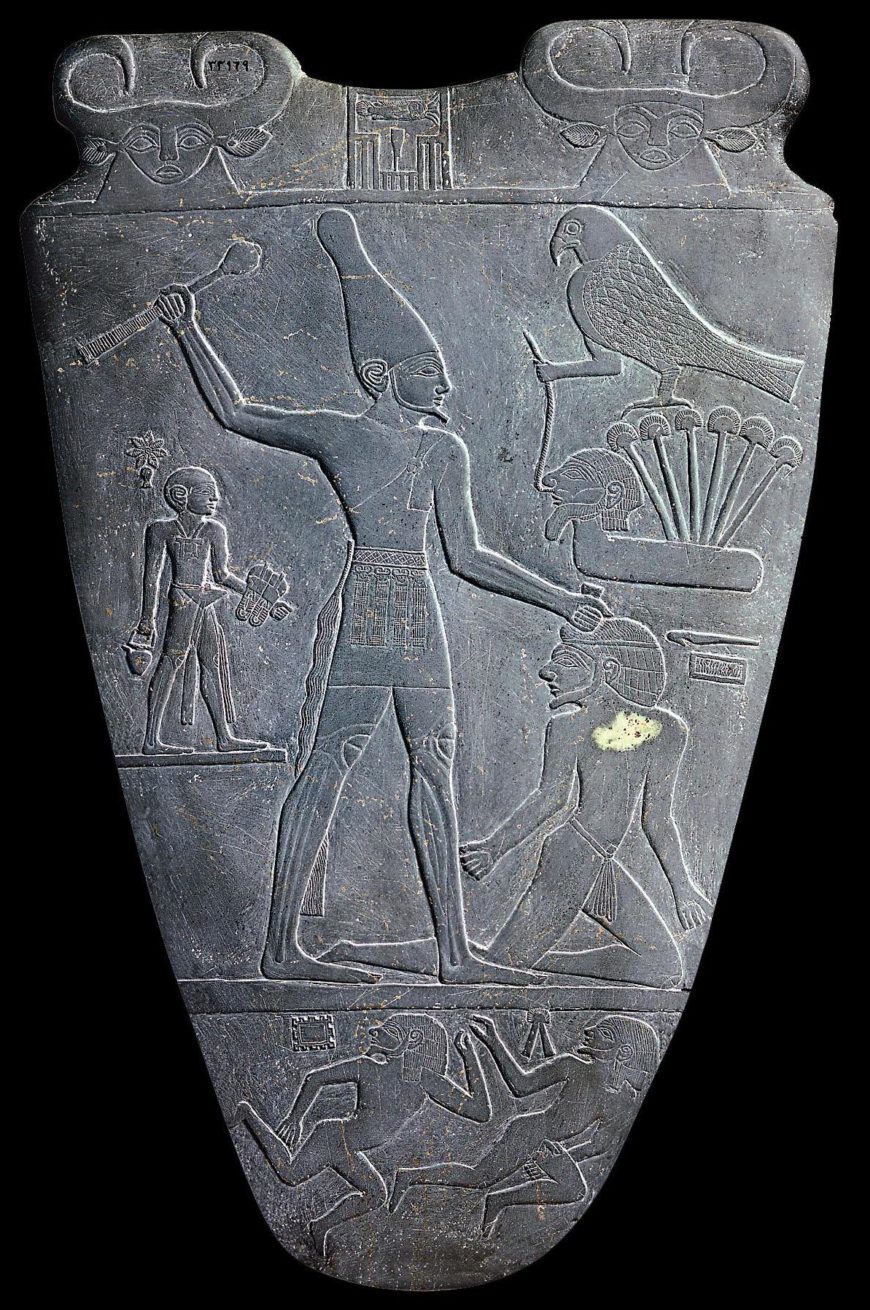

Palette of King Narmer, c. 3000–2920 B.C.E., Predynastic, greywacke (slate), from Hierakonpolis, 2′ 1″ high (Egyptian Museum, Cairo)

Pharaoh—Top of the Food Chain

Many aspects of royal ideology and iconography were visible from the earliest monuments and continued to be used for thousands of years. The Narmer Palette for example, includes the iconic smiting pose, elements of regalia like crowns, weapons, and the ceremonial beard, and a blending of divine and terrestrial elements in the same scene in support of the king’s efforts.

The ruler’s role as the champion of ma’at was paramount, as was the expectation that a ruler would protect Egypt from its enemies and administer the vast resources of the Two Lands to the benefit of the people. As time passed, the ruler had additional expectations, including being a good shepherd and protector and, in the militaristic period of the New Kingdom, to display great skill in battle and physical prowess.

Statue of King Khafre (Chephren), detail, 4th Dynasty, Old Kingdom, diorite, Giza, Egypt (photo: kairoinfo4u, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

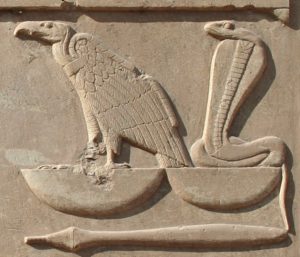

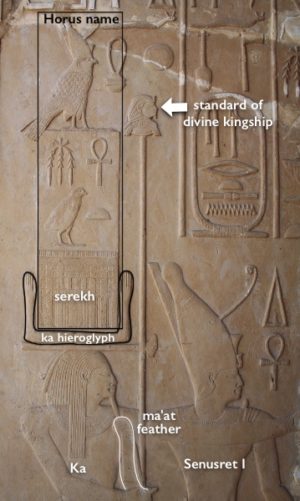

Kings in ancient Egypt were living humans, but they also embodied the eternal office of kingship itself. The ka, or spirit, of kingship was often depicted as a separate entity standing behind the human ruler, and it was this divine aspect of the office that gave authority to the individual person who was the king. The living ruler was viewed as the embodiment of the god Horus, the powerful, falcon-headed god who was believed to have bestowed the throne to the first human king, Menes. Once they died, the ruler became connected with Osiris, the eternal Lord of the Underworld, and their successor rose as the new Horus.

The ka of Senusret I stands behind the king and wears Senusret’s Horus-name in its serekh on his head, with the ka hieroglyph (a pair of upright arms) wrapped around the base. The ka holds an oversized ma’at feather and the standard of divine kingship (White Chapel, Karnak Temple)

Over time, the royal title developed so that each individual king had five names that emphasized different aspects of kingship and highlighted the king’s relationships with the gods.

Both the nomen and prenomen were enclosed in the elongated cartouche (an oval shape). This device, which may signify the infinite expanse of the king’s realm, clearly distinguished royal names from surrounding text.

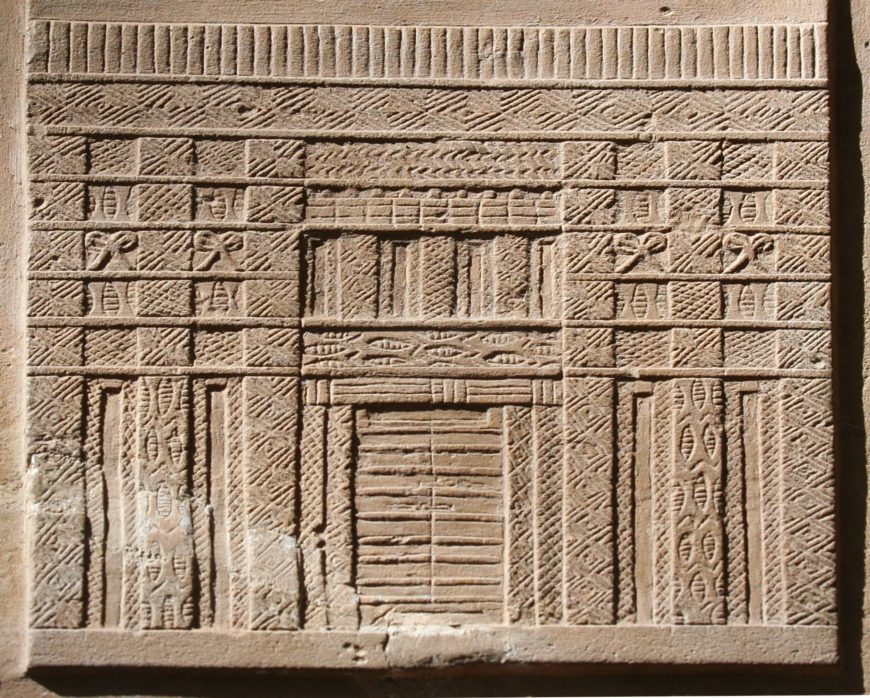

Detail of an elaborately patterned niched facade, known as a serekh, from the White Chapel of Senusret I, Karnak, Dynasty 12

Old Kingdom: First Dynasty through the First Intermediate Period

From the First Dynasty onwards, kings were known by the Horus-name. They served as political, religious, and military leaders. The ruler was expected to be the powerful champion of ma’at and capable of wielding that divine strength to protect Egypt from her foes.

The earliest sculptures of a specific ruler anywhere in the world may be two images of the Second Dynasty king Khasekhemwy wearing the White Crown and crushing chaotic enemies under his feet (one is pictured above) as an agent of ma’at. By the Fourth Dynasty, the king was viewed as the “Son of Ra,” acting as a deputy of the sun god on earth.

King Menkaura (Mycerinus) and queen (Old Kingdom), 2490–2472 B.C.E. (Menkaura Valley Temple, Giza), greywacke, 142.2 x 57.1 x 55.2 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Kings of the Old Kingdom were viewed almost as divine; statuary of this time shows them with perfected bodies and serene faces (like Menkaura and his queen) that seemed focused on the world beyond. Toward the end of the Sixth Dynasty, several factors (including low Nile inundations that may suggest famine and apparent disorganization), led to the loss of centralized control and the end of the Old Kingdom. Simultaneously, the prominence of local governors (nomarchs) began to increase in their individual regions and rise in importance. They became increasingly independent from the king and central administration, leading to a politically fractured period we call the First Intermediate Period.

Middle Kingdom through Second Intermediate Period

After the disunity of the First Intermediate Period, we see the democratization of previously royal prerogatives (such as the assumption of royal titles, regalia, and mortuary practices by local nomarchs), and the role of the pharaoh shifted. Kings of the Middle Kingdom focused more attention on being responsible protectors of Egypt, rather than on their divinity. Statues of the pharaohs from this time convey the heaviness of the crown and the role of kingship, the weight of their responsibilities evident on the face. The ears of these figures are also distinctly oversized—the better, it is believed, to hear the pleas of their people.

Face of Senwosret III (Middle Kingdom), c. 1878–1840 B.C.E., red quartzite, 16.5 × 12.6 × 11.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

During the Second Intermediate Period, peoples from western Asia took control of the Nile delta region. During this disjointed period, there was an Egyptian pharaoh ruling the south from Thebes and a Hyksos king ruling the north from a city called Avaris. Military conflicts between the two groups extended for generations and were fierce; one of the royal Egyptian mummies from this period shows severe injuries that indicate a violent death on the battlefield. Eventually, the pharaoh Ahmose was able to drive the occupiers out of the delta, re-unify the country under his rule, and establish the New Kingdom.

New Kingdom

After successfully regaining their country, New Kingdom rulers placed extra emphasis on military capabilities and were expected to be skilled in battle as the supreme commander of the armies. Perhaps in response to being invaded and occupied, the kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty led numerous military campaigns and expanded the borders of Egypt north all the way to the Euphrates river, and south deep into Nubia. Even after the borders were stabilized, this role of the king as Egypt’s protector was paramount, as evidenced by the huge numbers of triumphant battle scenes that appear on temple walls.

Temple of Queen Hatshepsut, Dayr al-Baḥrī, Egypt, c. 1470 B.C.E. (photo: Nuță Lucian, CC BY 2.0)

Female rulers

Female rulers, although rare, controlled the country at several points in Egypt’s history. One of the most famous of these was the powerful Hatshepsut, who reigned for around 20 years during the New Kingdom. A prolific builder, Hatshepsut’s magnificent terraced mortuary temple cut into the cliffs in west Thebes remains one of the most stunning structures from the ancient world.

Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut, c. 1479–1458 B.C.E., Dynasty 18, New Kingdom (Deir el-Bahri, Upper Egypt), granite, 261.5 x 80 x 137 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Many of Hatshepsut’s images show her as a masculine ruler, with her feminine characteristics deemphasized and wearing all the same royal regalia as male kings. Texts on these images, however, clearly identify her properly as female. As always before the gods, it was her capabilities as a good king that was of the greatest import; her gender was not an issue.

Granite shabti of the Kushite King Taharqa, 25th Dynasty, 664 B.C.E., from the pyramid of Taharqa at Nuri, Nubia, 40.6 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Rulers from abroad

Even rulers of non-Egyptian origin, including the much later Roman emperors who appear in temple relief carvings, presented themselves with the traditional iconography and regalia that clearly identified them as an Egyptian pharaoh. This practice linked them with the long line of kings that came before them and helped legitimize their rule to the illiterate populace. Rulers from Kerma, whose own culture displayed a fascinating blend of Nubian and Egyptian imagery, emphasized Egyptian deities in their monuments. These Kushite kings ruled Egypt for around 75 years. They were especially devoted to the god Amun, who had a well-established and important cult in their homeland.

King Lists

Kings recorded the names of their predecessors in vast “king-lists” on the walls of their temples and depicted themselves making offerings to the rulers who came before them—one of the best known examples is in the temple of Seti I at Abydos. These lists were often condensed, with some rulers (such as the contentious and disruptive Akhenaten and his successor, Tutankhamun) and even entire dynasties omitted from the record; they are not truly history, rather they are a form of ancestor worship, a celebration of the consistency of kingship of which the current ruler was a part.

Ancient Egyptian society has been portrayed as a pyramid, with the king at the very top and the population layered beneath them. Egypt was a theocratic monarchy, where the king ruled by the command of the gods and served as intermediary between the people and the divine. He was maintainer of ma’at, chief officiant in all ritual actions before the gods, military commander and protector of Egypt, living Horus, and provider for the people. If he fulfilled all his required roles to the satisfaction of the gods, then the land flourished and the people prospered. In general, the society was divided into those who administered (the officials) and those who were administered (the masses of the population). Given that there was no “church and state” separation, the temples were also part of the administration, lending divine oversight to state activities. All large-scale ventures, whether quarrying expeditions, building projects, or the maintenance of workshops of artisans, were controlled by the state.

To learn about the other layers of Egyptian society, please see: Egyptian Social Organization (Part 2)