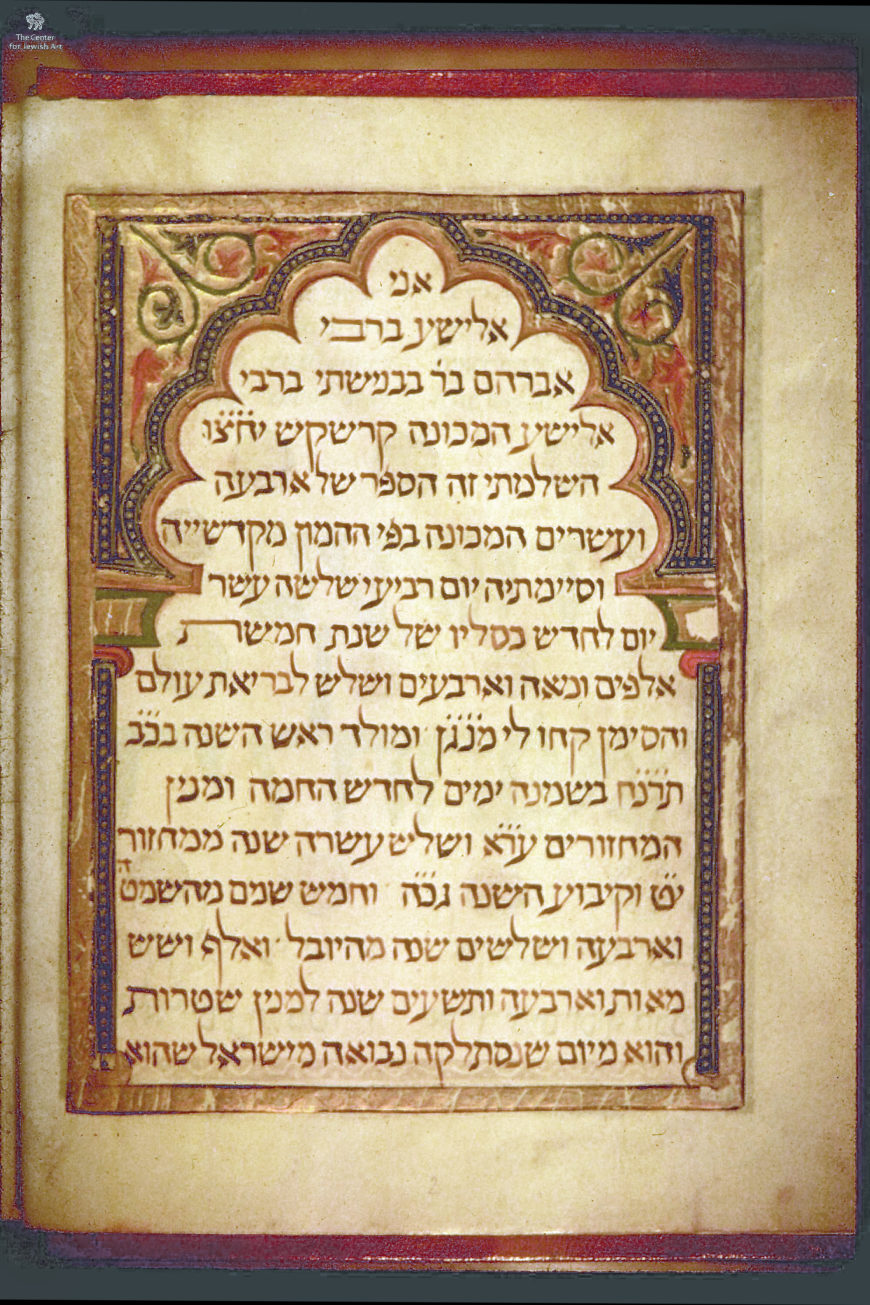

Colophon, Farhi Bible, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1366–83 (Center for Jewish Art) [1]

I Elisha, son of Rabbi Abraham Bevenisti, son of Rabbi Elisha, known by the name Cresques, finished this book of twenty-four [sections], commonly known as mikdashy’ah; I completed it on Wednesday, the thirteenth day of the month of Kislev in the year 5143 of the creation of the world (November 19, 1382)…. I collected [these texts] as a harvester from here and from there, so that neither I, nor my offspring will forget them; and God may help me to complete [the book], so that I will be able to read in it, I, and my children and the children of my children until the very last generation. Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, Farhi Bible

In these lines, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques declares the manuscript to be destined as a gift and resource for his descendants. Over 17 years, throughout much of his adult life, he painstakingly toiled over the manuscript, clearly evident in the eclectic combination of texts and the extensive decoration included on every page. Although titled, and referred to here, as the Farhi Bible, its name is misleading. The Bible’s name is not original to the manuscript, but rather comes from its 19th-century owner, Hayyim el-Muallam Farhi, the head of one of the most important Jewish families in Syria when that nation was part of the Ottoman Empire. In addition to the Bible, Farhi also owned Bayt Farhi, a remarkable house in the Old City of Damascus. Moreover, although described as a bible, the manuscript expands well beyond the traditional texts incorporated in a Hebrew Bible, including 194 pages devoted to such varied topics as Jewish and world history, approaches to determining the calendar, Hebrew grammar and pronunciation, biblical commentary, and Jewish law.

Through texts and images, Cresques hoped to pass down to his descendants a corpus of knowledge that reflected his cultural heritage. As a result, the manuscript’s contents and illuminations offer a window into the life of a prominent Jewish family living in 14th-century Majorca, an island off the coast of modern-day Spain.

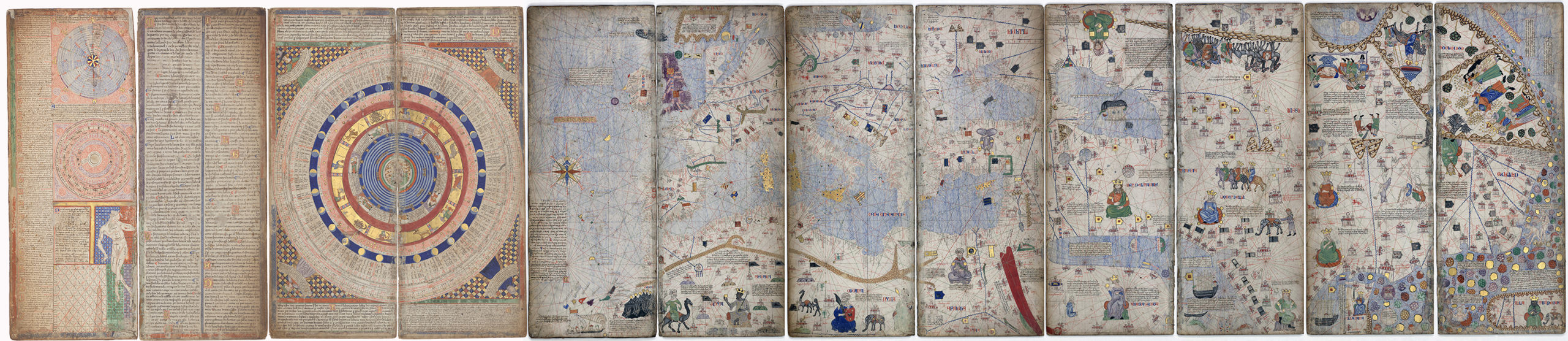

Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, Catalan Atlas, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Mapmaker, illuminator, scribe

While writing and illuminating the Farhi Bible was a personal project for Cresques, professionally, he was a celebrated map and compass maker. He was descended from a family of rabbis, and was an erudite scholar of both Jewish and secular matters. He likely received a traditional rabbinic education including training as a Hebrew scribe from an early age. In recognition of Cresques’s talent as a Hebrew scribe, his father donated a seat in their synagogue in his honor.

At some point later in life, Cresques also received professional instruction as an illuminator and cartographer. He was so talented that he received the title “master of world maps and compasses” (magister mapamundorum et buxolarum) from King Peter IV of Aragon, and served as the only documented mapmaker working for the Crown of Aragon. He is best known for his remarkable Catalan Atlas, a map of the world as it was perceived by western Europeans in the late 14th century. A royal commission for the King of Aragon, the Atlas reflects not only the patron’s needs but also Cresques’s own Jewish worldview.

Cresques and his family lived in the judería, or the Jewish quarter of Majorca. Majorca was home to a multilingual and multi-religious society, populated by Christians, Muslims, and Jews. This environment fostered engagement across religious boundaries within Majorca as well as across communities living in neighboring Arab regions. Cresques’s wife, Settadar, for example, was likely of Maghribi or North African origin. As a result, Cresques became intimately familiar with the languages and artistic traditions not only of Majorca and Christian Iberia, but also with the visual cultures of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, a Muslim-ruled region of southern Iberia, and Muslim-ruled North Africa.

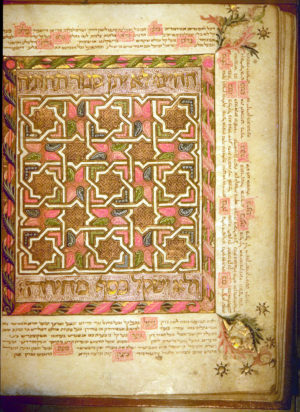

Carpet page, Farhi Bible, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1366–83 (Center for Jewish Art)

Cross-cultural exchange in the Farhi Bible

Cresques’s experiences in Majorca fostered a cultural flexibility that allowed him to easily move between different languages and traditions. As a result, he was able to develop a professional career at the court of Aragon, working for a predominantly Christian clientele. At the same time, he likely also served his local Jewish community as a Hebrew scribe and was able to create a manuscript steeped in his Jewish heritage. Across all of his works, and especially in the Farhi Bible, he approached the adornment of the manuscript through the artistic traditions of both Christian and Muslim Iberia.

Cresques’s bible follows in a long tradition of Sephardic Hebrew manuscript illumination, which began in the 1230s when Sephardic Jews began commissioning decorated bibles, and continued until the last decades of a Jewish presence in Iberia prior to their [simple_tooltip content=’The Alhambra Decree, or the Edict of Expulsion, of 1492, enacted by King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, expelled the Jews from the territories of the Crowns of Castile and Aragon.’]expulsion from Spain[/simple_tooltip] in 1492.

Typical of these bibles are Islamic-style carpet pages, featuring geometric and floral patterns common to Islamic book art. This repertoire of Islamicizing forms is evident throughout Cresques’s Farhi Bible. His colophon, for example, borrows from the architectural form of a mosque’s mihrab. Similar arched forms appear in manuscripts of the Qur’an as well, including as framing devices for colophons.

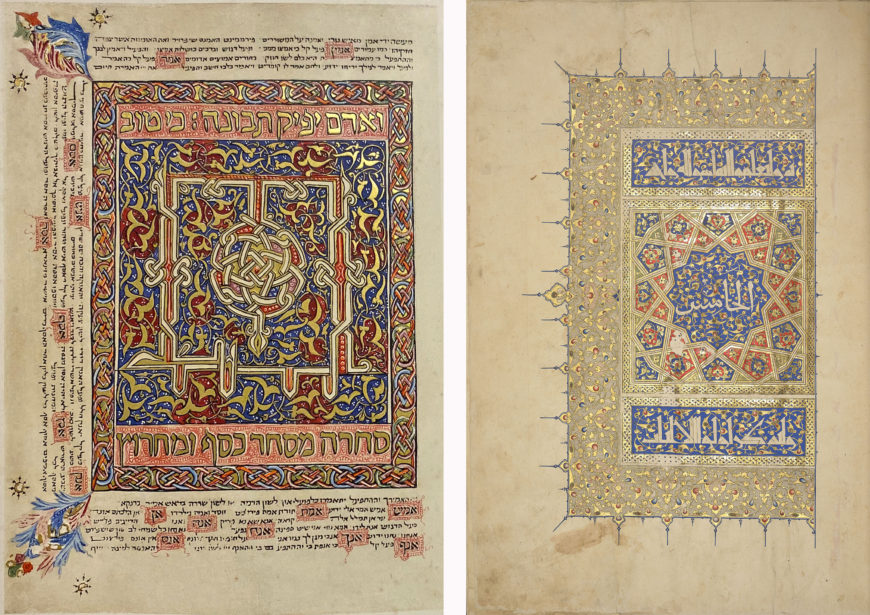

Left: carpet page, Farhi Bible, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1366–83 (Center for Jewish Art); right: carpet page, Sultan Baybars Qur’an, Egypt, early 14th century (British Library)

Following the colophon, the Farhi Bible opens with not one or two carpet pages (full-page illuminations), as is typical in Islamic and Hebrew manuscripts of the time, but thirty, which in their virtuosic ornamentation recall the dense interlace of 14th-century Islamic manuscripts, architectural decoration, and woodcarving in the Maghrib and Iberia. Each of the carpet pages is illuminated with a different pattern, all drawing upon the rich repertoire of Islamic forms. One carpet page, for example, centers on a circle formed of interlaced ribbons set against a background of scrolling golden vines. Above and below this central motif are horizontal bands with biblical verses praising the Torah (5 Books of Moses). This layout is indebted to manuscripts of the Qur’an, which similarly incorporate framing calligraphy to denote the beginning of a sura (chapter). The interlace ornament, and the similarity in the placement of the biblical passages as well as their content, echoing Quranic framing verses, highlights Cresques’s ongoing dialogue with contemporary Islamic culture. In addition, here and throughout the Bible, Cresques incorporated a color palette (red, pink, and white) and scrollwork ornament in the corners of the carpet pages more typically seen in Gothic manuscript illumination.

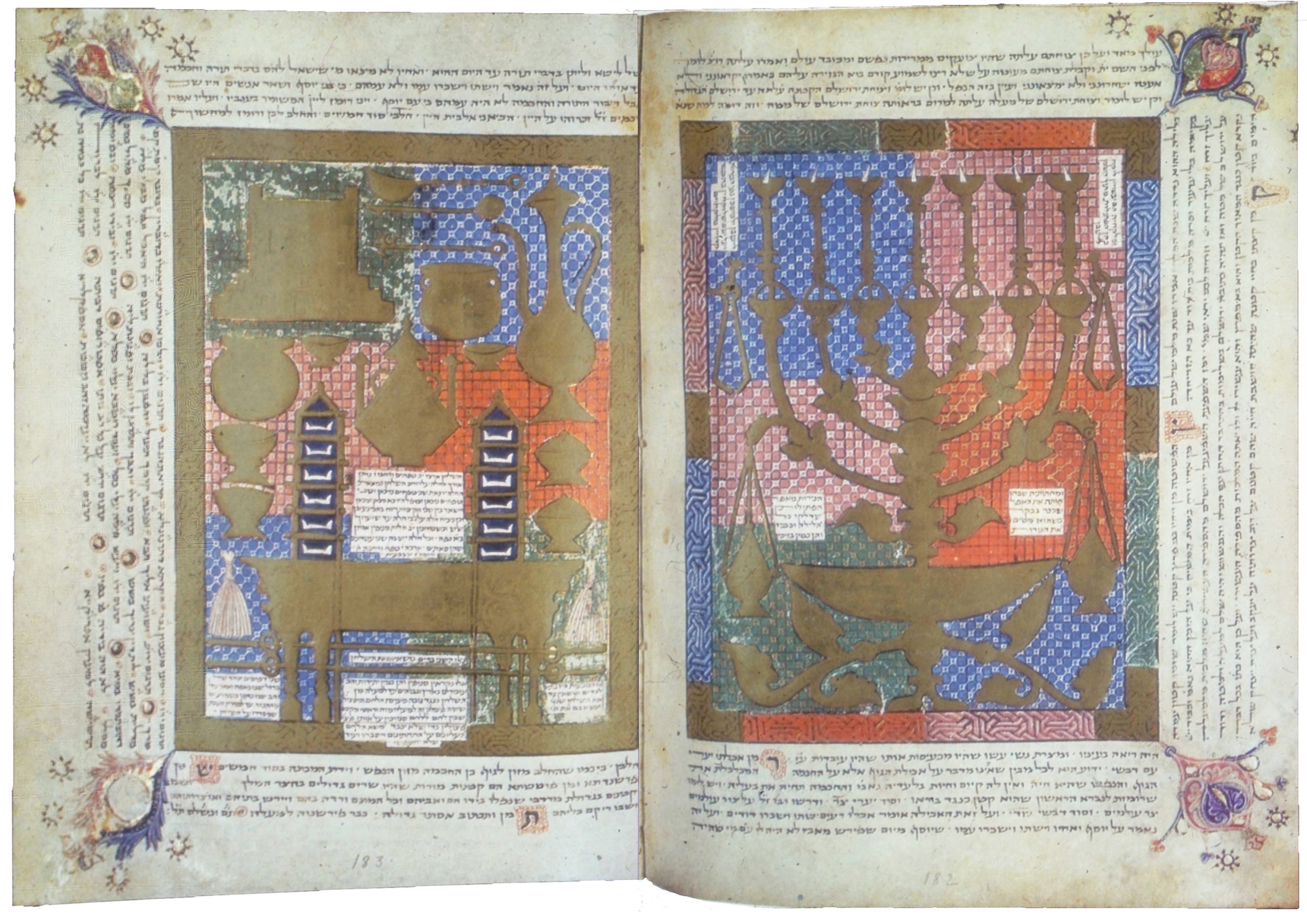

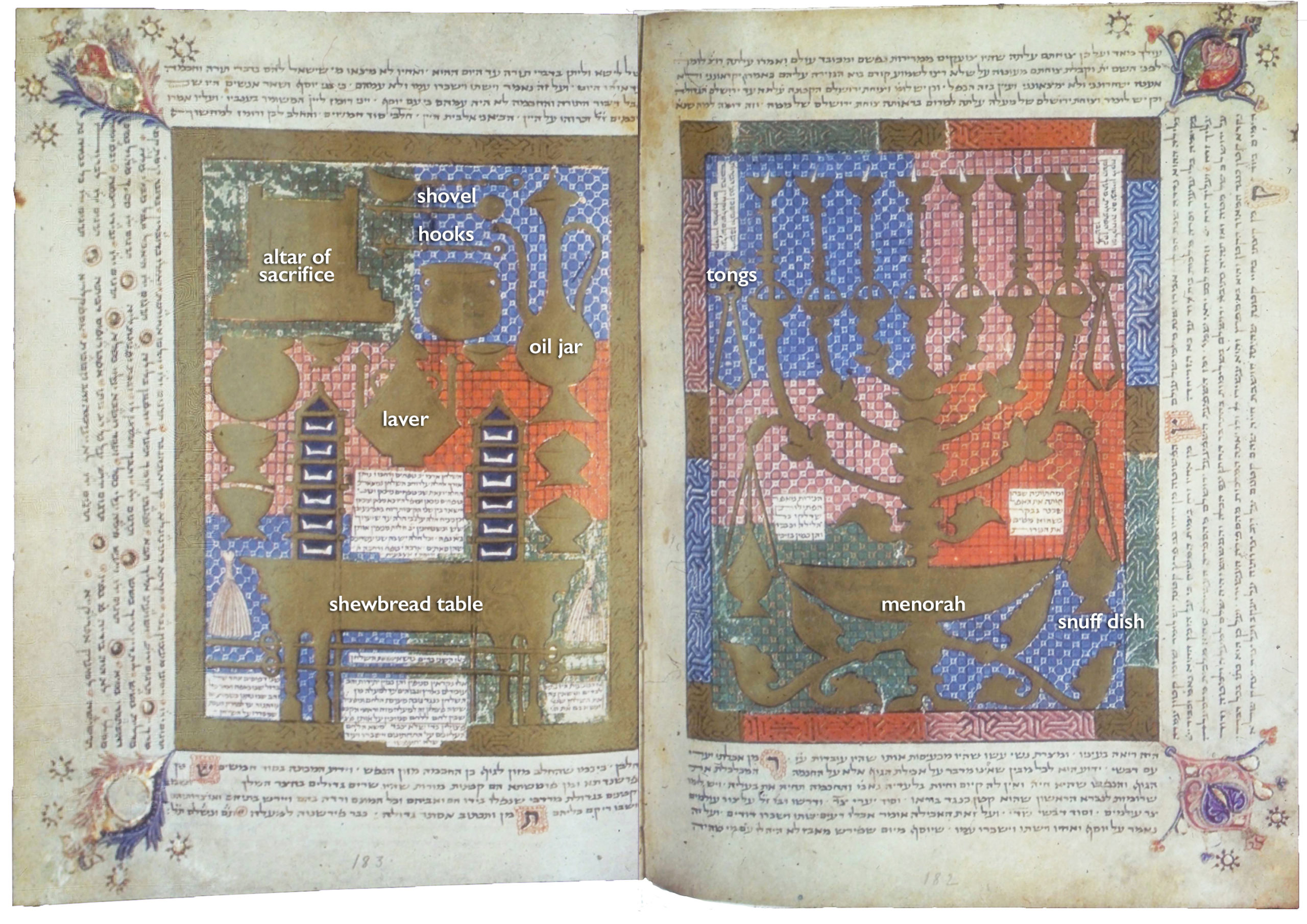

Motifs derived from a Gothic visual tradition are also apparent in two facing carpet pages in the middle of the manuscript which feature glittering illuminations of the vessels of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. These golden temple implements, including a full-page image of the menorah, as well as an oil jar, the sacrificial altar, and the shewbread table, among others, are positioned over a diaper pattern—a repeating geometric pattern common in Gothic manuscript illumination—in alternating compartments of red, pink, green, and blue.

Although the depiction of the temple vessels reflects biblical and rabbinic descriptions of the ancient Temple and its furnishings, their inclusion in the Farhi Bible, as well as in more than twenty surviving Sephardic Hebrew bibles, represented the Bible as a whole. Beginning in the early fourteenth century, Jewish communities across the Iberian Peninsula referred to their bibles by the epithet, or honorific title, “mikdashy’ah” (sanctuary of God), as a way of marking their understanding of the bible and Jewish liturgy as a replacement for the rituals practiced in the destroyed ancient Temple. In fact, Cresques refers to his bible as a mikdashy’ah in the bible’s colophon.

From generation to generation

In the borders of more than 120 pages of the Farhi Bible, Cresques included a Hebrew dictionary. Rather than a scholarly resource explaining the origins and meaning of various Hebrew words, the words are described using non-Hebrew equivalents, specifically words in Occitan, the spoken language of Majorca and of Elisha and his family. Such a tool may reflect Cresques’s fear that his offspring, in the face of growing persecution under Christian rule, would become so acculturated, that they would no longer be able to read and understand his bible without a Hebrew-Occitan dictionary. By including the dictionary and such a wide-ranging array of texts, he hoped that they would come to appreciate the depth of their heritage.

By the mid-fourteenth century, anti-Jewish sentiment in Majorca and across the Iberian Peninsula rapidly increased. Jews had long been required to wear a rodella, or a round red badge, as an identifying marker. Cresques himself, due to his high position at court as the King’s mapmaker, was exempt. But his family and friends were not as fortunate. Following the Black Death in 1348, in which, according to some estimates, nearly half of the population across Europe perished, Jews were unjustifiably blamed and persecuted. As the situation for Sephardi Jews rapidly deteriorated, Cresques spent the majority of his adult life creating a bible to preserve his religious and cultural heritage for his descendants.

Unfortunately, it is unlikely that the bible was used in the education of his children and grandchildren. In 1391, eight years after completing the manuscript and four years after his death, anti-Jewish riots spread across the Iberian Peninsula. At that time, Cresques’s entire family converted to Christianity under duress. His wife Settadar took the Christian name Anna, and shortly thereafter was forced to sell two family bibles as the family, once prominent and wealthy, fell into poverty.

Notes:

[1] The Farhi Bible was acquired by David S. Sassoon in the 1920s; although most of the Sassoon collection has recently been sold, the Farhi Bible remains in the possession of the Sassoon family. Slides, taken decades ago by the late Bezalel Narkiss, and now kept at the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, have been used in the essay above but do not do justice to the beauty of the illuminations.

Additional resources

Katrin Kogman-Appel, “Calligraphy and Decoration in the Farhi Codex (Sassoon coll. MS 368, Majorca, 1366–83), Sephardic Book Art of the Fifteenth Century, edited by Luís Alfonso and Tiago Mota (Harvey Miller Publishers, 2019), pp. 13–36.

Katrin Kogman-Appel, “The Scholarly Interests of a Scribe and Mapmaker in Fourteenth-century Majorca: Elisha ben Abraham Bevenisti Cresques’s Bookcase,” The Late Medieval Hebrew Book in the Western Mediterranean. Hebrew Manuscripts and Incunabula in Context, edited by Javier del Barco (Leiden: Brill, 2015), pp. 148–81.

Katrin Kogman-Appel, Jewish Book Art Between Islam and Christianity: The Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Spain (Leiden and Boston, 2004).

Jerrilyn D. Dodds, María Rosa Menocal, and Abigail Krasner Balbale, The Arts of Intimacy: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Making of Castilian Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008).