Pieter Jansz. Saenredam, Interior of Saint Bavo, Haarlem, 1631, oil on panel, 82.9 x 110.5 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Different church interiors — Calvinist (Protestant) and Catholic

In paintings by seventeenth-century Dutch artist Pieter Saenredam, the interiors of Calvinist churches often appear as blank, sterile spaces with white walls, clear glass windows, and a notable lack of decoration. We know from his meticulous preparatory drawings that Saenredam was a precise artist, and although he sometimes did make changes to the interiors he represented, they were by and large emblematic of what Dutch Calvinist sacred space was like. By contrast, Pieter Neefs’s contemporary paintings of Flemish Catholic religious spaces — which contain a profusion of small altars and devotional artwork — reflect a distinctly different attitude about decoration, materiality, and piety. The difference between Calvinist and Catholic churches persists to this day.

Breaking idols

Some of these differences can be attributed to two intertwined events of the sixteenth century that transformed the Low Countries (a lowland region in northern Europe that includes Belgium and the Netherlands): the prioritization of the written word in the theological reforms of the Protestant Reformation and the Iconoclasm (or Beeldenstorm) of 1566. The word “iconoclasm” refers to any deliberate destruction of images. Instances of iconoclasm can be found from the ancient world to contemporary events, such as the 2015 destruction of Palmyra in Syria by ISIS or the elimination of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban in 2001.

Workshop of Adam Dircksz, Prayer nut with The Nativity and The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1500 – 30, boxwood, silver, and gold, diameter 4.8cm (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

Here, iconoclasm specifically refers to the events of 1566 in an area that we now know as Belgium and the Netherlands. Prior to 1566, most churches in this region would have been largely encrusted with ornament: guilds commissioned altarpieces for their chapels while private patrons donated memorial paintings, endowed tomb sites, and donated elaborate shrines or ritual vessels. Piety was made visible in the material culture of the church, paralleling a northern European explosion in personal devotional artwork in the form of manuscripts, woodcut prints, carved boxwood shrines and prayer beads, and small paintings.

Protestant change

The sixteenth century was a time of significant religious change. According to legend, in 1516, Luther nailed his 95 Theses to a church door in Wittenberg and criticized what he perceived as corrupt practices within the Catholic Church. Following Luther, numerous other Northern European reformers shifted away from the Catholic Church centered in Rome. Among other more systemic and doctrinal issues, the reformers also had complicated relationships with religious imagery.

Controversy over the nature of religious images was not new in the sixteenth century. The same tension had rocked the Byzantine Empire in the eighth and ninth centuries. Like the earlier Byzantine case, strict reformers believed images were inherently sinful.

The northern humanist Desiderius Erasmus noted that the physical veneration of an object made it an active agent and turned it into an idol, pushing the objects and images traditionally at the heart of northern European piety into the zone of the idolatrous. Therefore, to use an image as part of your prayers creates idols — the very sin explicitly condemned in the Second Commandment, which reads:

You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; you shall not bow down to them or serve them; for I the LORD your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me, but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love me and keep my commandments. Exodus 20:3

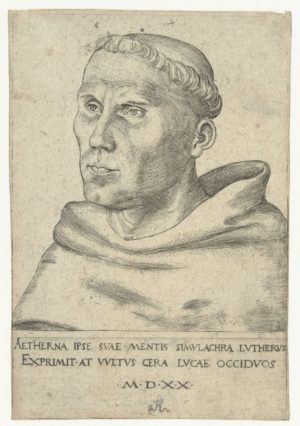

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Portrait of Martin Luther as an Augustinian monk, 1520 engraving, 14.4cm × 9.7cm (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

Luther himself was not entirely anti-image, stating that if there was no sin in the heart, there was no risk in seeing images with your eyes. However, the faithful needed to remove the roots of sin in themselves; they needed to worship God and not a material object which takes the place of God. Luther later clarified that what the second commandment prohibited was images of God; images of saints or crucifixes were not condemned by him as they serve as memorials.

By 1566, the debate about the line between “an image of a religious figure or story that aided in devotional practice” and “an idolatrous object which took the place of God in the sinful heart of the viewer” had been heavily contested for close to fifty years. The precise nature of the debate varied widely based on location, and violence against images erupted at different times in different cities throughout Germany, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Belgium, and England.

The debate about the nature of images seems abstract and it is impossible to know to what extent the theological details were the motivations of any specific iconoclast. In the case of the Beeldenstorm of 1566, we can focus on a few factors to more closely examine one particular case and the intersection of tensions that led to violence. Studying the Beeldenstorm is complicated by the fact that it took many different forms depending on the local conditions and the range of responses to both religious and political circumstance.

European territories under the rule of the Philip II of Spain around 1580, with the Spanish Netherlands in light green (public domain)

Church, state, and other complex issues

Debates over religious imagery occurred at the same time as other complex disputes. Political tensions were running high. At the time, most of the land that now constitutes The Netherlands and Belgium was the Spanish Netherlands — an assortment of territories brought together through marriages and dynastic alliances and owing fealty to the King of Spain.

Through the abdication of the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, Charles V, in 1556 and the ascension of Philip II to the throne of Spain, Netherlanders were becoming increasingly unhappy. The Spanish Crown supported an aggressive Catholic identity and agenda and vigorously pursued heretics (anyone not practicing Catholicism in line with the teachings of the Church in Rome).

The Spanish Inquisition existed specifically to root out those who were not Catholic enough. Though we tend to think of the Inquisition as something confined to the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal), it also had a significant impact on Northern Europe. A branch of the Inquisition operated there which was overseen by Margaret of Parma (the illegitimate daughter of Philip II who had been appointed regent and reported to her father). In response to petitions filed by the local nobility, Margaret ended the Inquisition in 1564 in an attempt to broker peace and avoid outright rebellion. A group who came to be called the Gueux brought further petitions in 1566 to try to end ongoing persecution. The tensions surrounding religious persecution were made worse by several bad harvests, prolonged and widespread famine, particularly harsh winters, and new taxes.

“Hedge preachers” as rebellious leaders

Religious, political, and economic issues were closely intertwined. To a Flemish Protestant, the Spanish Catholic Crown represented religious and political oppression. This was made worse by the widening cultural and linguistic gap between the Spanish Crown and its Flemish subjects. These tensions were brought to a boil by hagenprekers, or “hedge preachers,” wandering figures who whipped up anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic sentiment in sermons held outdoors, and usually outside of city walls and therefore beyond easy jurisdiction.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Sermon of Saint John the Baptist, 1566, 95 × 160.5 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest)

Several scholars have argued that Pieter Bruegel’s painting, The Sermon of Saint John the Baptist, represents this biblical event as if it were happening in the current political climate. John the Baptist, here cast as a hedge preacher, almost disappears into the crowd; Jesus, who he is introducing, is even less noticeable. Typically for Bruegel, the crowd of people gathered to listen to the speaker are from all walks of life and dressed in contemporary Flemish clothing.

Detail, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Sermon of Saint John the Baptist, 1566 (Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Sermon of Saint John the Baptist, 1566, detail (Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest)

One face stands out in the crowd because he unexpectedly faces the viewer: a man in a black hat having his palm read in the foreground. He would have been identifiable to contemporary viewers as dressed in a Spanish mode, and fortune telling would have been seen as corrupt and popish.

The Spaniard alone ignores the humble John the Baptist in favor of giving in to superstitious practices, while two monks in the front right look on with expressions that could be interpreted as jeers and skepticism. As a result, Bruegel’s painting possibly functions simultaneously as a biblical scene and a contemporary political polemic, containing just enough ambiguity to not ruffle Inquisitorial feathers.

Iconoclastic riots

The hedge preachers were at least partially responsible for the ignition of the Beeldenstorm, the sudden outbreak of violence against religious images that began in the summer of 1566 and spread throughout the Low Countries. In response to their anti-Catholic preaching, violence began in West Flanders and radiated outward.

In some towns, it was outright mob violence: groups of people burst into churches, smashing windows and sculptures. In other cities, the destruction of religious images was systematic and either openly or covertly supported by the local government. In some cases, the iconoclasts and the local Catholic Church officials negotiated for the survival of certain artworks.

Altar retable of the Jan van Arkel chapel, Utrecht Cathedral (Domkerk). Found behind a false plaster wall during restoration activities in 1919. Dated 15th century, defaced during the Beeldenstorm (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

It was a fever that spread throughout the Low Countries, leaving few towns untouched by the sudden explosion of anti-image sentiment. According to Alistair Duke, the destruction of images functioned as a ritualistic act intended to prove to both Catholics and Protestants that the images were powerless. If images were indeed sacred conduits that connected the faithful to God, they would defend themselves; since it was possible to destroy them, they were therefore earthly vanity and merely distractions from truth.

To destroy the objects and ritually humiliate them was to reject the broader political and religious structures they represented, as well. Sculptures were torn down from their niches, windows were smashed, and altars and shrines were disassembled and burned.

When the sculptures were part of the fabric of the building and could not be easily removed, the heads of the figures were hacked off. Examples reflecting this kind of violence remain visible in churches throughout the Northern Low Countries inside previously Catholic, now Protestant churches.

Jan Luyken, Beeldenstorm, 1566, etching, 27cm × w 34.8cm (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

Iconoclasm in 1566 was not just the result of doctrinal disagreement about the nature of religious imagery and the interpretation of biblical text. It was instead a response to intertwined issues of politics, religious oppression, and economic factors. It was one spark that helped ignite the flames of the Eighty Years War, a war that ultimately resulted in the split between the northern Calvinist provinces of the Dutch Republic and the southern Catholic province that remained connected to Spain. As much as the violence of the Beeldenstorm itself may have been short-lived, the broader cultural and historical changes that cascaded as a result had permanent and far-reaching consequences.

Additional resources:

Read more about the Beeldenstorm in the Low Countries Historical Review

David Freedberg, The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1989).

Alistair Duke, “Calvinists and Papist Idolatry: the Mentality of the Image-breakers in 1566,” in Dissident identities in the early modern Low Countries, ed. Pollman and Spicer (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2009).