Fajada Butte, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Chacoan petroglyphs can be found at the base of the cliffs (photo: Adam Meek, CC BY 2.0)

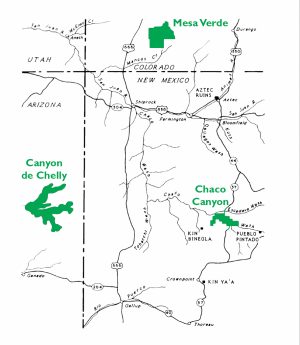

Map of major ancestral Puebloan sites in the Four Corners region (National Park Service)

New Mexico is known as the “land of enchantment.” Among its many wonders, Chaco Canyon stands out as one of the most spectacular. Part of Chaco Culture National Historical Park, Chaco Canyon is among the most impressive archaeological sites in the world, receiving tens of thousands of visitors each year. Chaco is more than just a tourist site however, it is also sacred land. Pueblo peoples like the Hopi, Navajo, and Zuni consider it a home of their ancestors.

The canyon is vast and contains an impressive number of structures—both big and small—testifying to the incredible creativity of the people who lived in the Four Corners region of the U.S. between the 9th and 12th centuries. Chaco was the urban center of a broader world, and the ancestral Puebloans who lived here engineered striking buildings, waterways, and more.

Chaco is located in a high, desert region of New Mexico, where water is scarce. The remains of dams, canals, and basins suggest that Chacoans spent a considerable amount of their energy and resources on the control of water in order to grow crops, such as corn. Today, visitors have to imagine the greenery that would have filled the canyon.

Astronomical observations clearly played an important role in Chaco life, and they likely had spiritual significance. Petroglyphs found in Chaco Canyon and the surrounding area reveal an interest in lunar and solar cycles, and many buildings are oriented to align with winter and summer solstices.

The great kiva at Chetro Ketl, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Great Houses

“Downtown Chaco” features a number of “Great Houses” built of stone and wood. Most of these large complexes have Spanish names, given to them during expeditions, such as one sponsored by the U.S. army in 1849, led by Lt. James Simpson. Carabajal, Simpson’s guide, was Mexican, which helps to explain some of the Spanish names. Great Houses also have Navajo names, and are described in Navajo legends. Tsebida’t’ini’ani (Navajo for “covered hole”), nastl’a kin (Navajo for “house in the corner”), and Chetro Ketl (a name of unknown origin) all refer to one great house, while Pueblo Bonito (Spanish for “pretty village”) and tse biyaa anii-ahi (Navajo for “leaning rock gap”) refer to another.

Multistoried rooms, Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (photo: Jacqueline Poggi, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Pueblo Bonito is among the most impressive of the Great Houses. It is a massive D-shaped structure that had somewhere between 600 and 800 rooms. It was multistoried, with some sections reaching as high as four stories. Some upper floors contained balconies.

There are many questions that we are still trying to answer about this remarkable site and the people who lived here. A Great House like Pueblo Bonito includes numerous round rooms, called kivas. This large architectural structure included three great kivas and thirty-two smaller kivas. Great kivas are far larger in scale than the others, and were possibly used to gather hundreds of people together. The smaller kivas likely functioned as ceremonial spaces, although they were likely multi-purpose rooms.

Doorway, Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon (photo: Thomson20192, CC BY 2.0)

Among the many remarkable features of this building are its doorways, sometimes aligned to give the impression that you can see all the way through the building. Some doorways have a T shape, and T-shaped doors are also found at other sites across the region. Research is ongoing to determine whether the T-shaped doors suggest the influence of Chaco or if the T-shaped door was a common aesthetic feature in this area, which the Chacoans then adopted.

Recently, testing of the trees (dendroprovenance) that were used to construct these massive buildings has demonstrated that the wood came from two distinct areas more than 50 miles away: one in the San Mateo Mountains, the other the Chuska Mountains. About 240,000 trees would have been used for one of the larger Great Houses.

Chacoan Cultural Interactions

Traditionally, we tend to separate Mesoamerica and the American Southwest, as if the peoples who lived in these areas did not interact. We now know this is misleading, and was not the case.

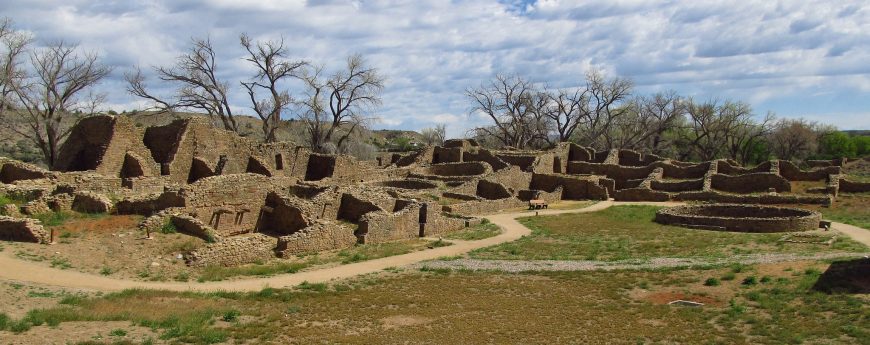

Chacoan culture expanded far beyond the confines of Chaco Canyon. Staircases leading out of the canyon allowed people to climb the mesas and access a vast network of roads that connected places across great distances, such as Great Houses in the wider region. Aztec Ruins National Monument (not to be confused with ruins that belonged to the Aztecs of Mesoamerica) in New Mexico is another ancestral Puebloan site with many of the same architectural features we see at Chaco, including a Great House and T-shaped doorways.

Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico (photo: Jasperdo, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Cylindrical Jar from the Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, 3 5/8 inches in diameter (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

Archaeological excavations have uncovered remarkable objects that animated Chacoan life and reveal Chaco’s interactions with peoples outside the Southwestern United States. More than 15,000 artifacts have been unearthed during different excavations at Pueblo Bonito alone, making it one of the best understood spaces at Chaco. Many of these objects speak to the larger Chacoan world, as well as Chaco’s interactions with cultures farther away. In one storage room within Pueblo Bonito, pottery sherds had traces of cacao imported from Mesoamerica. These black-and-white cylindrical vessels were likely used for drinking cacao, similar to the brightly painted Maya vessels used for a similar purpose.

The remains of scarlet macaws, birds native to an area in Mexico more than 1,000 miles away, also reveal the trade networks that existed across the Mesoamerican and Southwestern world. We know from other archaeological sites in the southwest that there were attempts to breed these colorful birds, no doubt in order to use their colorful feathers as status symbols or for ceremonial purposes. A room with a thick layer of guano (bird excrement) suggests that an aviary also existed within Pueblo Bonito. Copper bells found at Chaco also come from much further south in Mexico, once again testifying to the flourishing trade networks at this time. Chaco likely acquired these materials and objects in exchange for turquoise from their own area, examples of which can be found as far south as the Yucatan Peninsula.

Current Threats to Chaco

The world of Chaco is threatened by oil drilling and fracking. After President Theodore Roosevelt passed the Antiquities Act of 1906, Chaco was one of the first sites to be made a national monument. Chaco Canyon is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Chacoan region extended far beyond this center, but unfortunately the Greater Chacoan Region does not fall under the protection of the National Park Service or UNESCO. Much of the Greater Chaco Region needs to be surveyed, because there are certainly many undiscovered structures, roads, and other findings that would help us learn more about this important culture. Beyond its importance as an extraordinary site of global cultural heritage, Chaco has sacred and ancestral significance for many Native Americans. Destruction of the Greater Chaco Region erases an important connection to the ancestral past of Native peoples, and to the present and future that belongs to all of us.

Additional resources:

Chaco Canyon UNESCO World Heritage Site webpage

“Unexpected Wood Source for Chaco Canyon Great Houses” from the University of Arizona

Stephen H. Lekson, ed. The Architecture of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007).