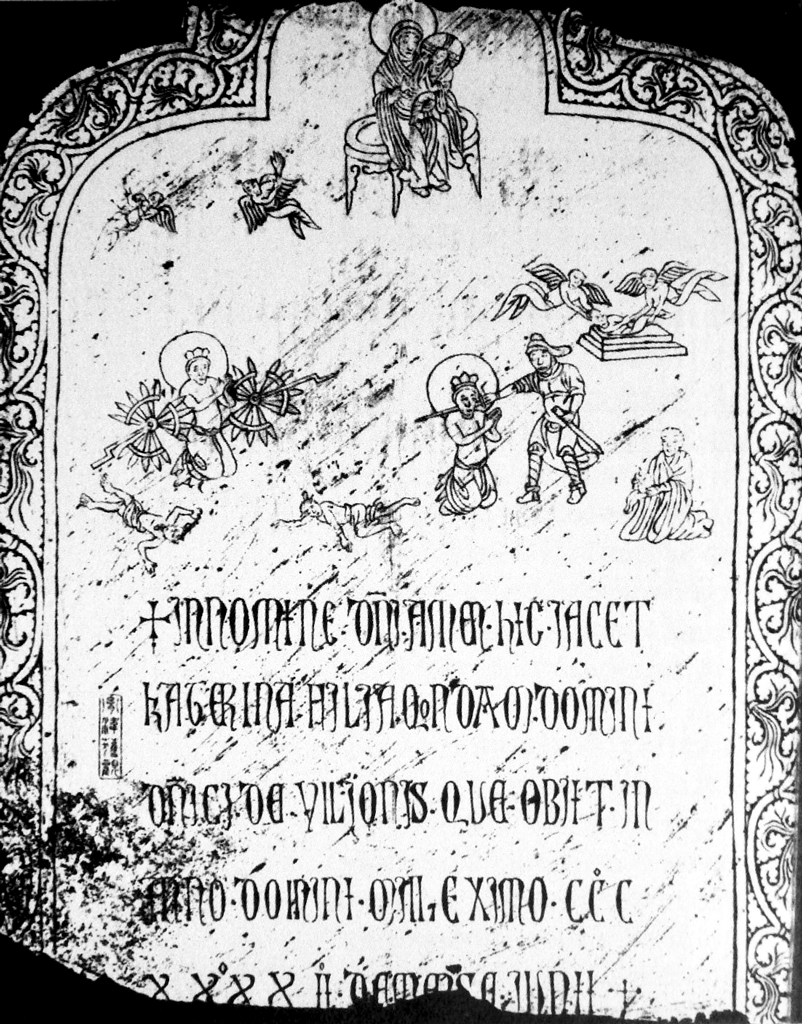

Caterina Vilioni’s tombstone, 1342, stone, 58 cm high (Yangzhou Museum; photo: Deborah Howard)

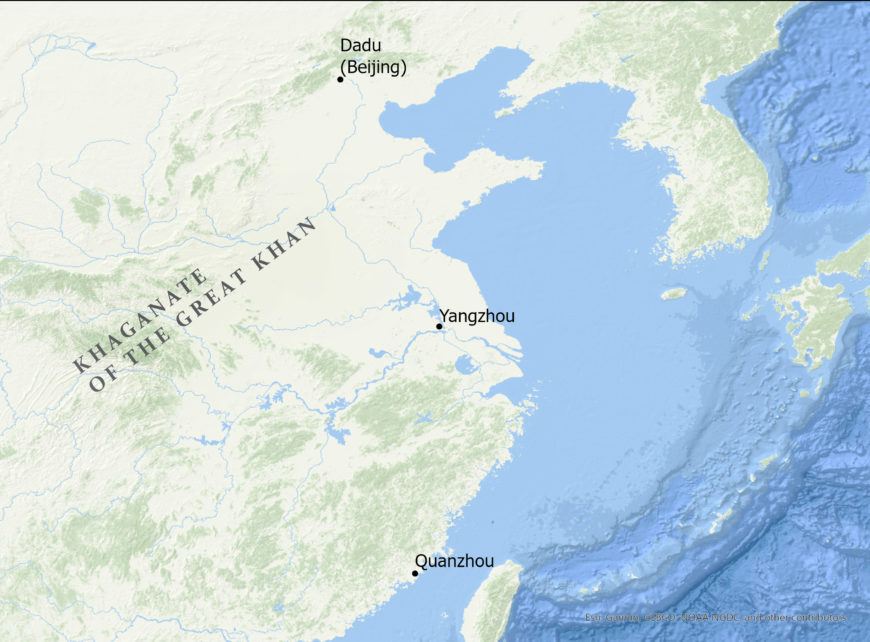

In 1951, a late medieval Christian tombstone with Latin inscriptions was discovered during road construction at the south gate of Yangzhou (扬州市) in current-day Jiangsu province in eastern China. It survives in excellent condition, and only the bottom of the grey stone slab has been broken off. According to the inscription, the tombstone commemorated the death of Caterina Vilioni, daughter of Domenico Vilioni, in June 1342. While no other surviving written sources attest to the existence of Caterina, her funerary monument is a rare and important testimony to the presence of western European Christianity in Yuan China (1271–1368 C.E.).

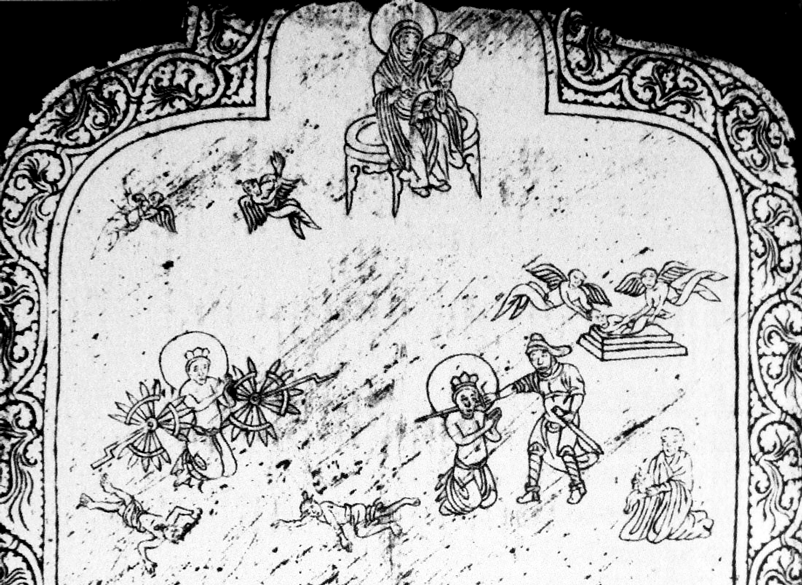

The monument is decorated with scenes from the martyrdom of the patron saint of Caterina Vilioni, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, and it also includes an image of the seated Virgin and Child. While the iconography originates from Christian hagiography, some of the details, like the executioner dressed as a contemporary Chinese soldier, draw attention to a complicated interplay between both European and Asian artistic features. The fourteenth century was characterized by a continuous and ever-increasing flow of people and goods between Europe and Asia. The amalgamation of diverse visual traditions in Caterina’s tombstone highlights the need to consider the complex cultural and social framework in which it was created.

Religious plurality in Yangzhou

The tombstone was commissioned during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), when China was controlled by the Mongols (who are not ethnically Chinese). The Mongol regime implemented a new policy that ranked Mongols first, then non-Mongol and non-Chinese foreigners, then northern Chinese, and lastly southern Chinese people. The new scheme increased the influx of foreigners into China and enhanced religious plurality and tolerance.

The presence of Europeans is recorded in numerous cities in China, including Dadu (modern Beijing), Yangzhou, Fuzhou, and Zayton (modern Quanzhou). From these places, however, only Quanzhou and Yangzhou preserved funerary monuments associated with European Christians (for reasons unknown). While thirty tombstones were preserved from Quanzhou, only two survive from Yangzhou and both are decorated with sophisticated narrative imagery. Moreover, a Franciscan missionary from Italy, Odorico da Pordenone, recorded the presence of a Franciscan convent in Yangzhou when he travelled through the city in 1322. This is remarkable considering the Franciscan order was only founded in 1209 in Assisi, Italy.

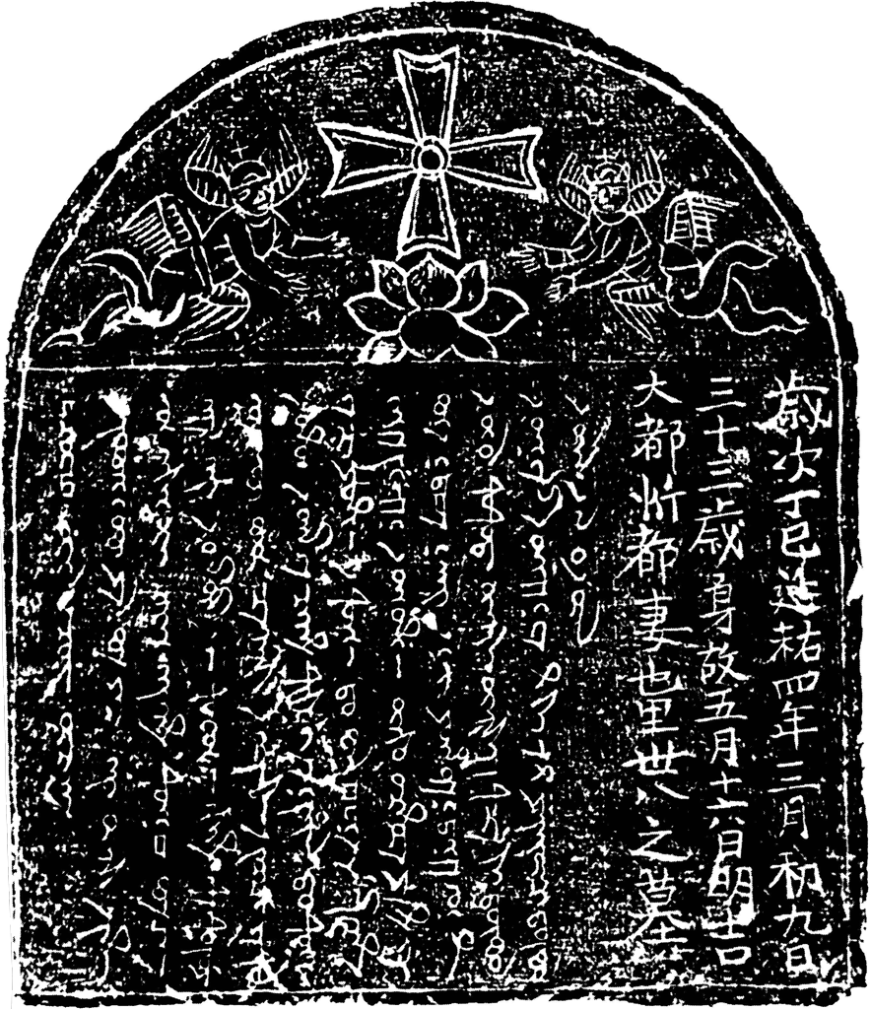

Nestorian stele (detail), 781, limestone, h. 279 cm. (Xi’an, Beilin Museum; photo: David Castor, public domain)

Christianity in China

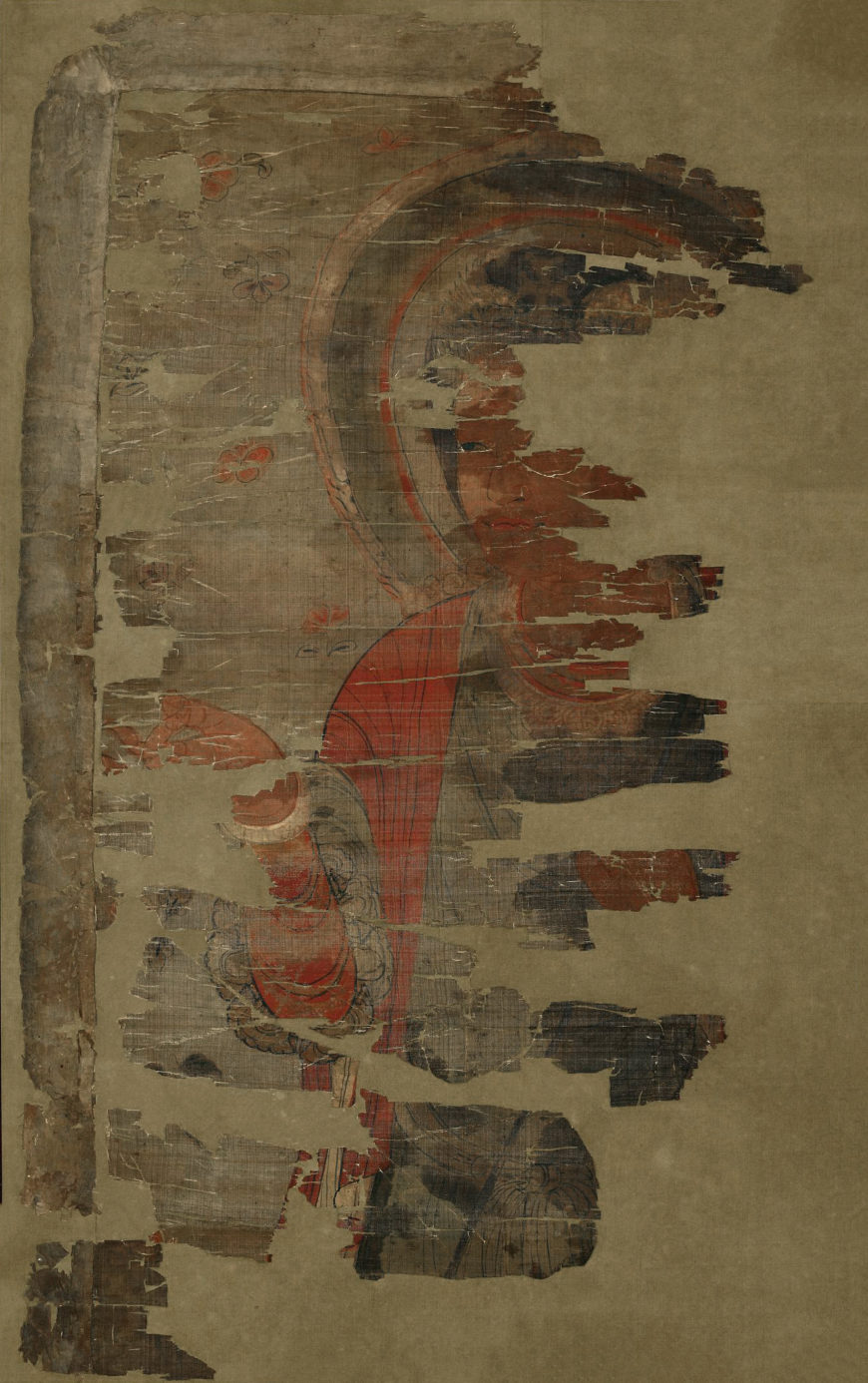

Christianity was already present in China at least sporadically by the seventh century. Material culture is especially illuminating in tracing the early history of Chinese Christianity. A number of Nestorian steles (upright stone slabs) can be immediately recognized by their inclusion of a cross. One of the earliest surviving examples is a large stele from 781, currently in the Beilin Museum. Here, a small cross is engraved immediately above the writing, towards the top. Nestorian murals also depict Christian scenes such as those at Qocho from the seventh or eighth century. These fragmentary wall paintings depict Palm Sunday, the Entry into Jerusalem, and a scene with a repentant figure.

Jesus or a Christian Saint from Dunhuang (Mogao Caves: Cave 17), 9th century, paint on silk, 88 x 55 cm. (The British Museum)

The British Museum’s rare ninth-century silk painting of a holy man with a headdress decorated with a cross from the Tang dynasty possibly represents Jesus. The steles and paintings indicate that Christians (including the Nestorians, a Christian Mongol group known as the Keraites, and others) had a long history in parts of China over time.

Boucicaut Master, Marco Polo with Elephants and Camels arriving at Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, c. 1410–1412, tempera on vellum, Ms Fr 2810 f.14v (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Europeans in China and the Vilioni

The famous Venetian explorer, merchant, and travel writer Marco Polo travelled through Asia along the Silk Road. He set out from Venice in 1271 and reached China in 1275, eventually returning to his homeland. The great number of surviving illuminated manuscripts recounting Marco Polo’s adventures attest to the fascination with Asia in late medieval Europe. In an image within a 15th-century manuscript, Marco Polo is shown arriving at Hormuz in the Persian Gulf accompanied by elephants and camels.

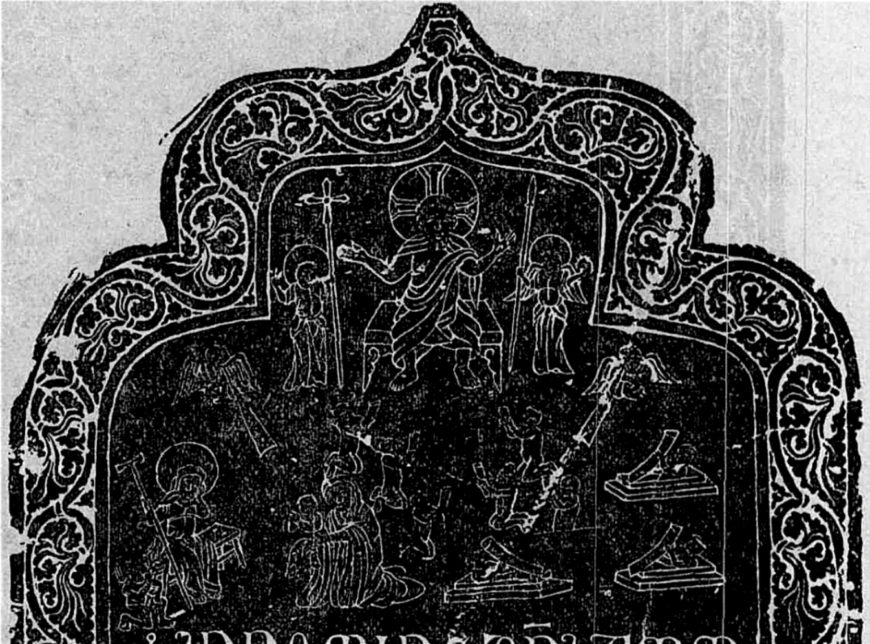

Some Europeans even settled more permanently in China. The Vilioni family originated from Italy, possibly from Venice or Genoa. Written sources attest that members of this family were present in Asia, including China and Iran, as merchants in the thirteenth century. Moreover, the tombstone of Caterina’s brother, Antonio ( who died in 1343), was also discovered in Yangzhou in the same area.

This tombstone bears a similar Latin inscription to Caterina’s, confirming that Antonio’s father was also Domenico Vilioni, and it is decorated with images of the Last Judgment and Saint Anthony. Both Caterina’s and Antonio’s tombstones suggest that the Vilioni family settled in Yangzhou, probably as merchants, trading goods such as silk, spices, or other lucrative commodities. While Europe’s emerging merchant class was not yet as wealthy as it would become in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, participating in the expanding long-distance trading networks could be a profitable opportunity.

The Martyrdom of St Catherine of Alexandria

Caterina’s tombstone, like her brother’s, is a rare surviving example of a Christian tombstone in China that includes narrative imagery. It is decorated with scenes from the martyrdom of one of the most popular holy virgins of late medieval Christianity, Saint Catherine of Alexandria. According to her hagiography, Catherine lived in Alexandria, Egypt in the early fourth century, where the pagan Roman emperor Maxentius condemned her to death for her faith. She was tortured, and attempts were made to kill her in various ways, including trying to break her body on a spiked wheel, which, however, shattered at her touch.

Bartolomeo Bulgarini, St Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1335–1340, tempera and gold leaf on panel, 73.5 × 42 cm (National Gallery of Art)

This wheel subsequently became her most popular identifying attribute. For instance, a panel by the Italian painter Bartolomeo Bulgarini shows Saint Catherine resting her book on the wheel that is prominently positioned.

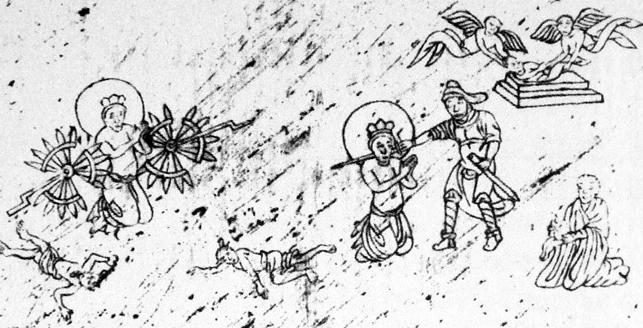

As the first scene of a narrative sequence, the Yangzhou tombstone shows the scene of the breaking of the wheel in action on the lower left edge of the composition. The saint is envisioned kneeling in prayer, surrounded by two splintering wheels, while two male bodies lay dead in the foreground. On the right side, Catherine’s martyrdom appears as she is being beheaded with a sword. Above, two angels are burying her corpse in a tomb. On the right edge of the composition a man holds an infant, probably representing the soul of Caterina Vilioni, which echoes the deceased’s hope for salvation.

Altichiero da Zavio, Beheading and funeral of St Catherine of Alexandria, 1378–1384, fresco, oratory of San Giorgio, Padua

Numerous similar narrative cycles with scenes from the life and martyrdom of St Catherine of Alexandria survive from across late medieval Europe. The wall paintings by Altichiero da Zavio in the oratory of San Giorgio in Padua represent a monumental example. Catherine kneels on the right of the composition as she prepares to be beheaded.

Donato or Gregorio d’Arezzo, Saint Catherine of Alexandria and Twelve Scenes from Her Life, c. 1330, tempera and gold leaf on panel, 107 × 174 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

The altarpiece attributed to Donato or Gregorio d’Arezzo frames the standing central figure of the saint with twelve smaller scenes. Amongst these are the breaking of the wheels (the center scene, far right), the beheading, and the enshrinement of the corpse, similarly to the Vilioni tombstone (the two final scenes, bottom right).

Liu Guandao (劉貫道), Kublai Khan on the Hunt, 1280, paint on silk (Taipei, National Palace Museum)

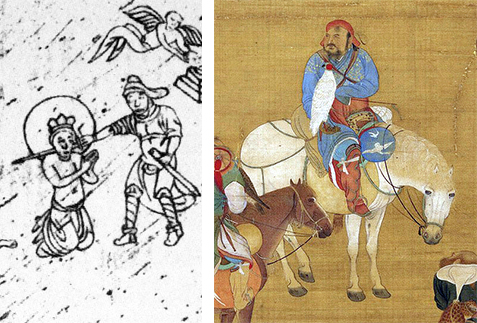

Caterina’s tombstone, however, also shows some unique artistic features. For example, the executioner is enrobed in the armor of a contemporary Mongol soldier, complemented with a characteristic hat with an ear-shaped piece of cloth flipped backwards. Similar garments and hats appear for example in a silk painting depicting the Hunt of Kublai Khan from around 1280, attributed to the Chinese court artist Liu Guandao (劉貫道).

Left: detail of drawing of Caterina Vilioni’s tombstone; right: Liu Guandao (劉貫道), Kublai Khan on the Hunt, 1280, paint on silk (Taipei, National Palace Museum)

Herman, Paul, and Jean de Limbourg, “Angels Carry the Body of Saint Catherine to Mount Sinai,” Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, 1405–1408/9, tempera and gold leaf on vellum, 23.8 x 16.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Nonetheless, some of the details are more ambiguous. For instance, the angels are represented in a manner similar to late medieval European examples such as the illumination of the Belles Heures of duc de Berry. In both cases, the legs of the angels are covered by their robes.

However, similar figures also appear in Chinese art, including the winged creatures on the murals from the sixth century in the Dunhuang caves (such as Mogao Cave 285). These caves are situated at religious and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, in current-day Gansu province in China. Their decoration, a key testimony of Buddhist art, has been executed over a nearly thousand-year long period.

Other fitting examples, which are also associated with Italians in China, are the angels on the tombstone of Andrew of Perugia which was discovered in Quanzhou. Andrew was a Franciscan friar who was sent to China in the early fourteenth century by the pope as part of a missionary embassy. In 1322, he became the bishop of Quanzhou, where he died around 1332. Similarly to that of Caterina and her brother, the tombstone of Andrew of Perugia is one of the few surviving figural funerary monuments associated with European Christians in China. However, Andrew’s tombstone offers an example for a different visual model, decorated with a non-narrative composition.

These analogies raise awareness about the complicated chain of associations when interpreting the imagery of Caterina’s tombstone. Some of the artistic features could originate either from European art, but just as easily from Chinese. It seems likely, however, that the anonymous master who decorated the tombstone was informed to a certain extent by both.

The Virgin Mary and Guanyin

The topmost image on Caterina’s tombstone is the Virgin and Child enthroned. A roughly contemporary sarcophagus that bears the arms of the Sanguinacci family (possibly from the Veneto region in Italy) from the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century is adorned with a similar image.

Sarcophagus with Virgin and Child and the Arms of the Sanguinacci Family, late 13th century–early 14th century, red limestone, 82.6 x 223.5 x 94 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This characteristic Christian iconography could have transferred to China through small, mobile objects such as ivories or illuminated manuscripts. However, in contrast to the Italian Madonna’s throne, on the Yangzhou tombstone Mary is sitting on a squat little chair which is similar to stools common in contemporary China. For instance, a woman is sitting on such a chair on the left side of a garden terrace scene on a carved red lacquer plate from the Yuan dynasty. This feature thus further highlights the entanglement of different visual influences in the imagery of the tombstone.

Garden Terrace Scene, detail of a plate, 14th century, carved red lacquer, diam. 55.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Moreover, the haloed figure of the Virgin Mary is remarkably similar to Guanyin (觀音). Originally a male figure in the Buddhist pantheon, this bodhisattva became a popular female deity in thirteenth-century China as the child-giving Guanyin. She sometimes appears with a child on her lap, and her head is often framed by the moon in a strikingly similarly manner to that of the Virgin Mary by her halo.

Zhang Yuehu (張月壺), White-Robed Guanyin (白衣觀音), late 1200s, hanging scroll, ink on paper, 104 x 42.3 cm (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

A complex web of associations

Despite the extremely scarce surviving written evidence, Caterina Vilioni’s tombstone offers invaluable insight to the presence of Christian and especially of European women in thirteenth-century China. At the same time, this tombstone exemplifies artistic patronage connected to an ordinary woman, the daughter of a merchant, instead of a representative of elite society. Moreover, its imagery draws attention to social and religious plurality in early Yuan China. The intricate combination of the diverse visual features rendered Caterina’s tombstone meaningful to both European and local audiences, even if for different reasons and on different levels.

Additional resources:

Francis A. Rouleau, “The Yangchow Latin Tombstone as a Landmark of Medieval Christianity in China,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies vol. 17, no. ¾ (1954), pp. 346–365

Lauren Arnold, Princely Gifts and Papal Treasures: The Franciscan Mission to China and Its Influence on the Art of the West, 1250-1350 (San Francisco: Desiderata Press, 1999)

Jennifer Purtle, “The Far Side: Expatriate Medieval Art and Its Languages in Sino-Mongol China,” in Confronting the Borders of Medieval Art, ed. Jill Caskey, Adam S. Cohen, and Linda Safran (Leiden: Brill, 2011), pp. 167–197