Two Jewish emigres from Europe were at the forefront of chromolithography, a printing process that gained immense popularity in the years around the U.S. Civil War, and allowed for mass-produced colored images: Julius Bien and Max Rosenthal. Due to their low production costs, Americans could decorate their homes with these inexpensive prints, and so millions of brightly hued, eye-catching chromolithographs soon hung in homes across the country. Chromolithograph techniques were employed widely: for advertisements, posters, postcards, and reproductions of fine art.

Julius Bien after John James Audubon, “Seaside Finch; and Grafs Finch or Bay-Winged Bunting” from Birds of America, 1858, chromolithograph, 68.9 x 101.6 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

Julius Bien and the Birds of America

Julius Bien after John James Audubon, “Summer, or Wood Duck” from Birds of America, 1860, chromolithograph, 101.6 x 66.04 cm (Portland Art Museum)

Bien’s magnum opus was an edition of artist-naturalist John James Audubon’s the Birds of America (1858–60). Bien consulted the original color drawings by Audubon for his edition, rather than depending on the copper plates that had been used as a model for earlier editions. The book has been lauded as a landmark in the chromolithographic process in the United States, and widely admired for its soft, more accurate color varieties. Unfortunately, financial troubles of the Audubon family who were subsidizing the venture, the advent of the Civil War, and newer scientific approaches in ornithology halted the project with only 150 of the original 435 species serially produced and eventually bound in one volume. If Bien’s project had been realized, it would have allowed for a relatively inexpensive and more accessible edition of Audubon’s work.

Bien received valuable training in the technique of color lithography in his native land of Germany, acquiring techniques still unknown in America. After fighting in the 1848 Revolution, he emigrated to New York, where he lived a life in the service of the Jewish people and art.

Bien led B’nai B’rith as the organization’s president for over three decades, just as comfortably as he did in his ten-year presidency of the National Lithographers’ Association. His technical proficiency and attention to detail as a printer of maps included service to the Union side during the Civil War, to Pacific Railroad surveys, and to U.S. census reports for forty years. Aided by artists in his large workshop, which employed over two hundred artists, Bien was recognized as the most prolific and respected practitioner in the field. Bien’s work was also acclaimed by the larger public, winning medals at the world expositions in Paris, Philadelphia, and Chicago.

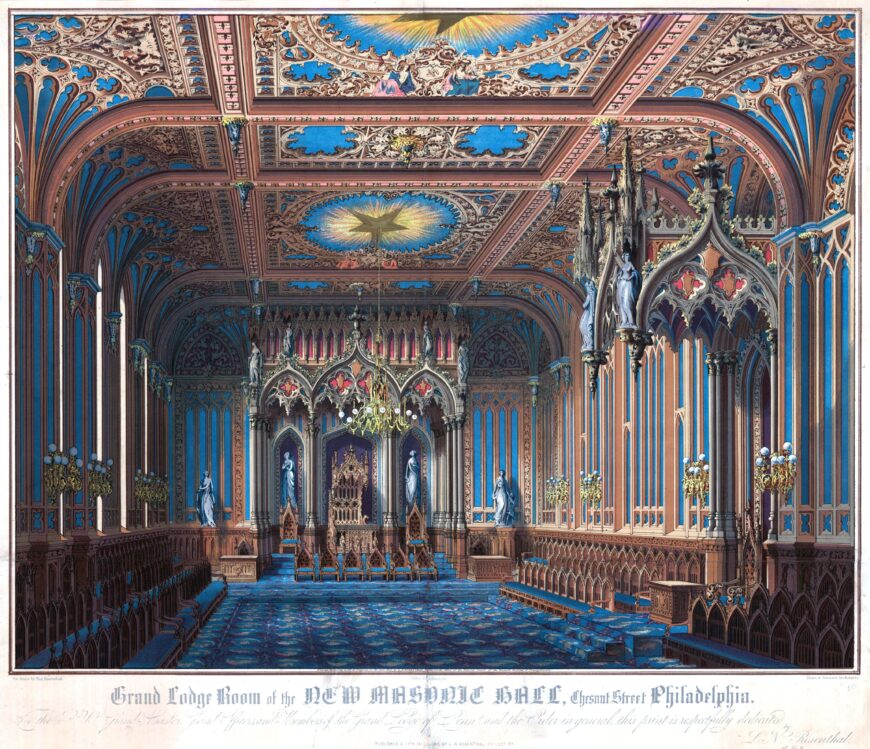

Max Rosenthal, Grand Lodge Room of the New Masonic Hall, Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, 1855, chromolithograph, 53 x 67 cm (Library of Congress)

Max Rosenthal

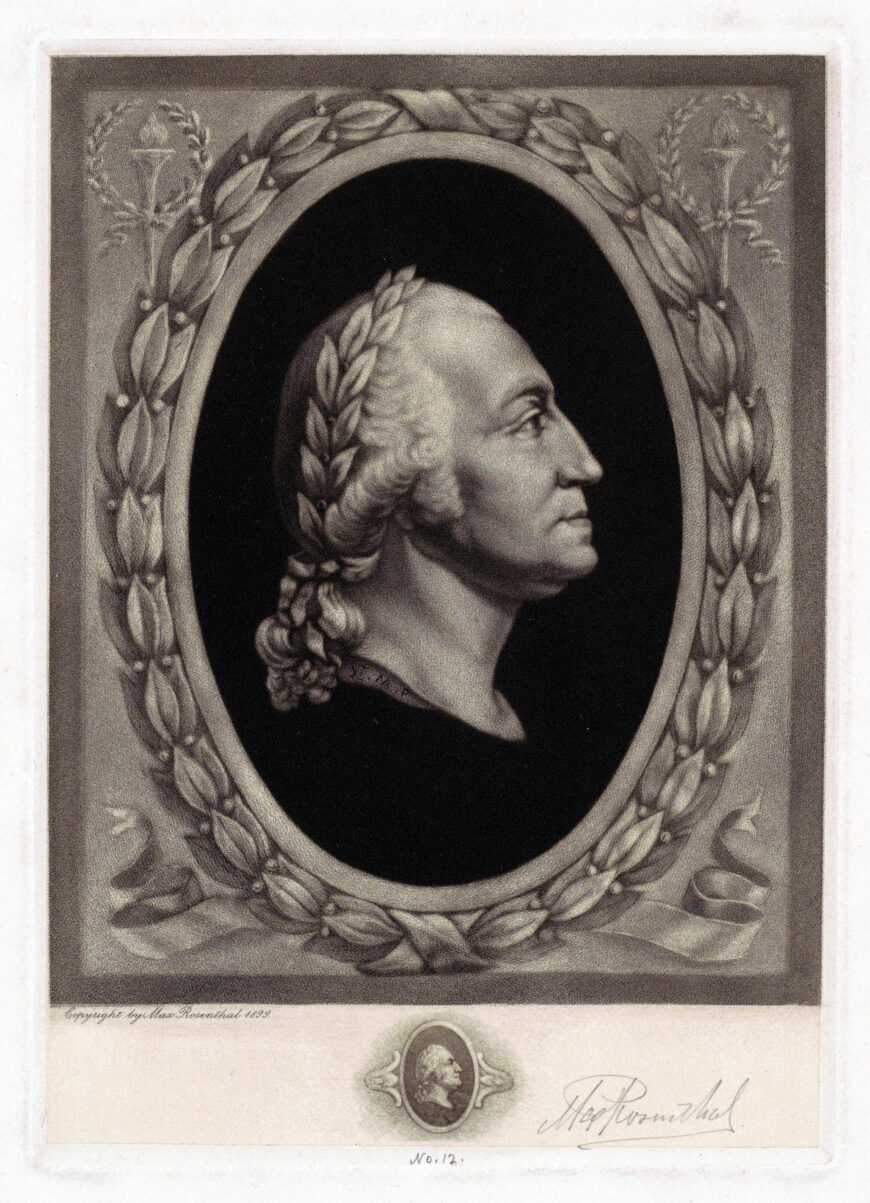

Max Rosenthal, George Washington, 1899, mezzotint, 14.92 x 12.07 cm (National Gallery of Art)

Following study in Berlin and Paris, Max Rosenthal settled in Philadelphia, enrolling in classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The Rosenthal brothers—Lewis, Maurice, Solomon, Simon, and Max—established a profitable family lithography business, with Max as the primary artist. The firm printed a variety of images, from city views to sheet music covers to advertisements. Max’s interior view of the grand lodge room of Philadelphia’s Masonic Temple (1855), made after his own design, measures 22 by 25 inches, and was the largest American chromolithograph to date. This commemorative print of the newly-built structure features the vibrant colors of chromolithographs, especially in the turquoise hues featured throughout the ornate Gothic architecture, patterned carpet, and cushioned benches.

Like artists Moses Jacob Ezekiel and Henry Mosler, Rosenthal’s career was touched by the U.S. Civil War; he served as official illustrator for the United States Military Commission, sketching army camps, which he translated into lithographs. Later he found appreciation for his technically rich mezzotint portrait engravings of distinguished Americans, after original American paintings by other artists, as well as his own, on occasion.

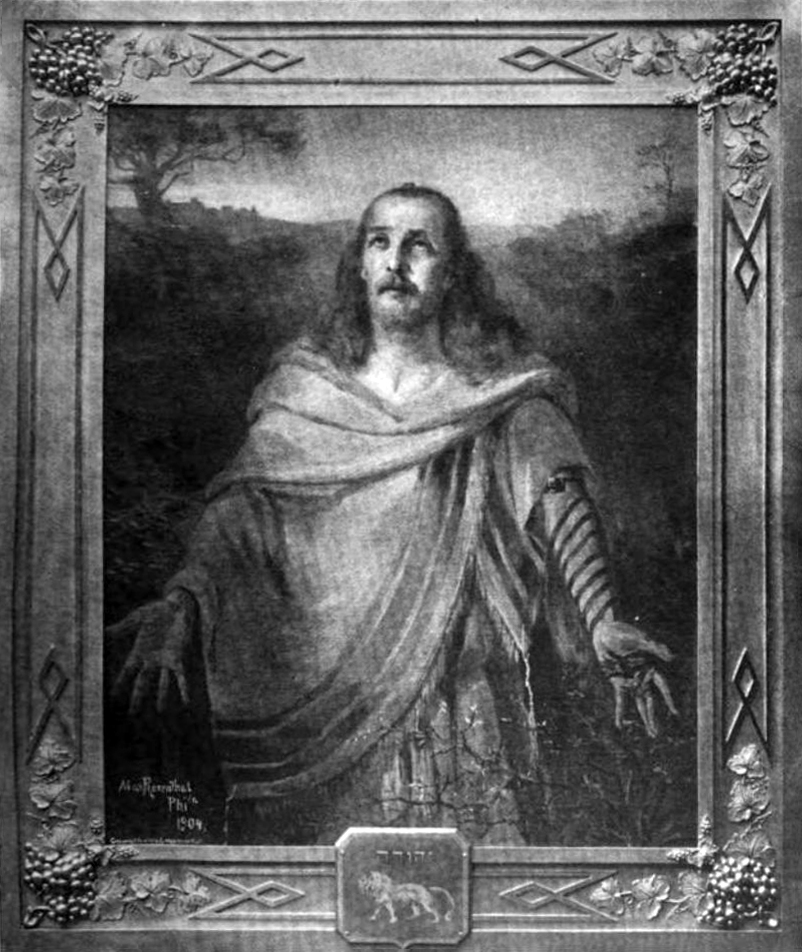

Black-and-white photograph of Max Rosenthal, Jesus at Prayer, 1904, now lost (photo: New Era Illustrated Magazine)

Rosenthal attained some notoriety for daring to show Jesus as a Jew—with Semitic features and wearing a tallit and phylacteries—in a painting titled Jesus at Prayer (now lost). At the bottom right corner of the canvas a thorny bush presages Jesus’s fate. Each corner of the specially designed ornate frame featured plentiful grapes, a symbol of the Eucharist or, as reported in the Jewish press, mistakenly, a symbol of Judah. More easily identified is the lion carved at bottom center, surely symbolizing the Tribe of Judah, with Judah’s name printed in Hebrew. Painted on commission for a Protestant church in Baltimore, the altarpiece, as to be expected, was promptly rejected by its Christian patrons.

In defense of the conception, one writer countered that in art, over the ages, “Jesus has been everything, except what he was—a Jew. . . . His [Rosenthal’s] readings in the New Testament have given him no reason to believe that all the Jewish customs in regard to prayer were not observed by Jesus…. Mr. Rosenthal has, therefore, painted Jesus standing erect and open-eyed, instead of kneeling with bowed head, as Christian painters have been accustomed to represent him, an attitude unknown among Jews, and therefore unlikely to have been assumed by Jesus.” [1] Rosenthal himself understood the canvas, which he said was the dream of his life to paint, not “as a religious, but distinctly as an historic picture, aiming at conscientious accuracy.” [2]

Left: Mark Antokolsky, Christ before the People’s Court, 1876, marble, 195 cm high (Haifa Museum of Art; photo: shakko, CC BY-SA 3.0); right: Moses Jacob Ezekiel, Ecce Homo, c. 1886–89, bronze, 8.2 x 38.7 x 32.3 cm (Cincinnati Art Museum)

It is worthy of note that at the same time in Europe, Jewish artists—Polish painter Maurycy Gottlieb; Russian sculptor Mark Antokolsky; German painter Max Liebermann; and German Zionist graphic artist Ephraim Moses Lilien—were producing imagery of Jesus, very much portrayed as a Jew. In a handful of sculptures, Moses Jacob Ezekiel stressed Jesus’ Jewish origins as well. Ezekiel originally titled his Ecce Homo (1886–89), a powerfully built bronze torso with a heavy beard and a pronounced crown of thorns, Christ Represented as a Jewish Martyr.

Max Rosenthal, Interior view of Independence Hall, Philadelphia, c. 1865, chromolithograph, 33 x 47 cm (Library Company of Philadelphia)

Conclusion

Not only did Bien and Rosenthal follow their artistic muse, they demonstrated entrepreneurial skills, honing in on a new and profitable artistic field that broadened the market for art beyond the elite. Both artists left inhospitable conditions in their native countries in hope of a better life, and in doing so made crucial contributions to a new mode of art in their adopted homeland.