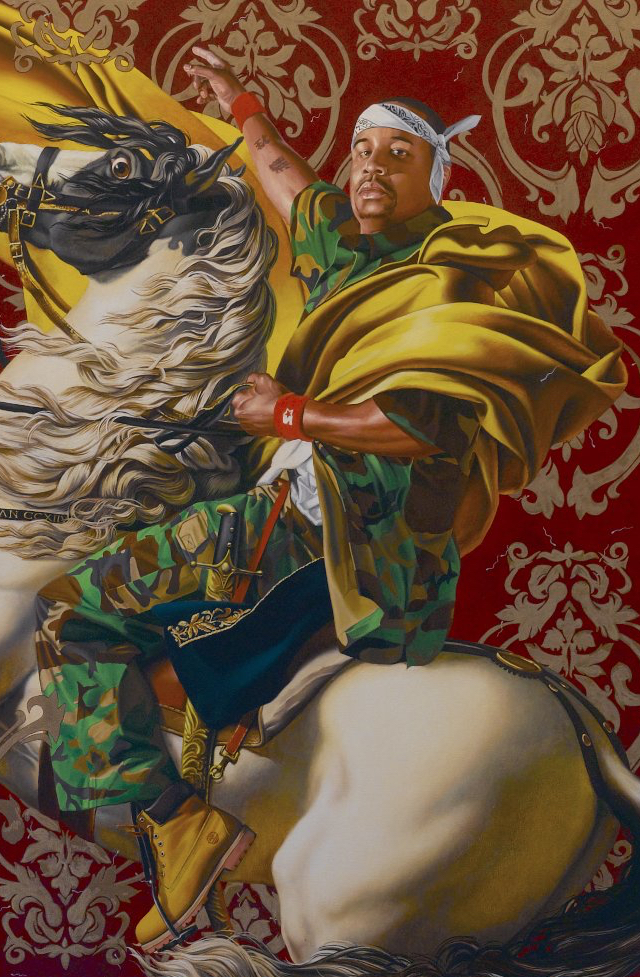

Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005, oil on canvas, 274.3 x 274.3 cm (Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York) © Kehinde Wiley

Confronting art history

In this large painting, Kehinde Wiley, an African-American artist, strategically re-creates a famous French painting from two hundred years before but with key differences. This act of appropriation reveals issues about the tradition of portraiture and all that it implies about power and privilege. Wiley asks us to think about the biases of the art historical canon (the set of works that are regarded as “masterpieces”), representation in pop culture, and issues of race and gender. Here, Wiley replaces the original white subject—the French general-turned-emperor Napoleon Bonaparte—with an anonymous Black man whom Wiley approached on the street as part of his “street-casting process.” Although Wiley does occasionally create paintings on commission, he typically asks everyday people of color to sit for photographs, which he then transforms into paintings. Along the way, he talks with those sitters, gathering their thoughts about what they should wear, how they might pose, and which historical paintings to reference.

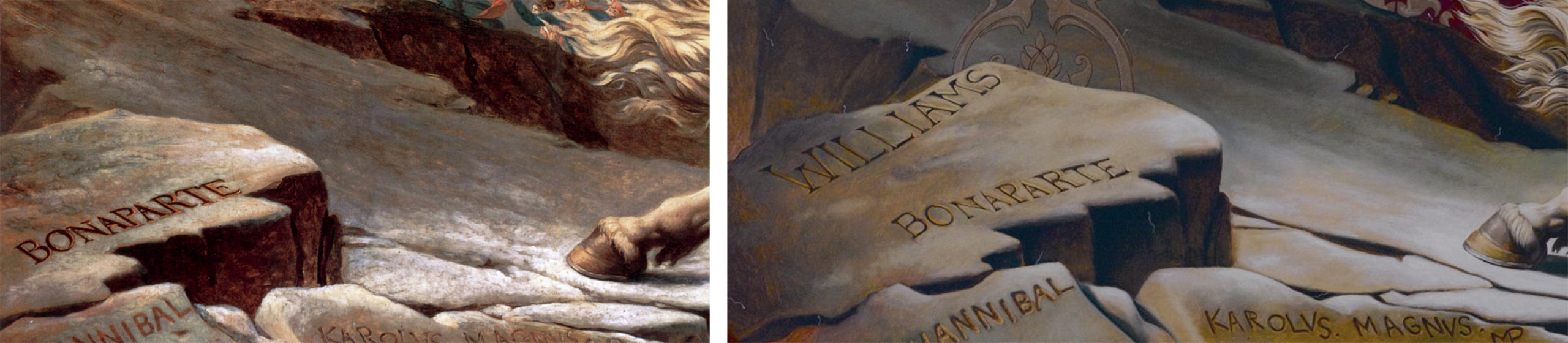

Left: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps or Bonaparte at the St Bernard Pass, 1801 version, oil on canvas, 275 x 232 cm (Österreichische Galerie Belvedere); right: Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005, oil on canvas, 274.3 x 274.3 cm (Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York) © Kehinde Wiley

Napoleon Leading the Army is a clear spin-off of Jacques-Louis David’s painting of 1801, which was commissioned by Charles IV, the King of Spain, to commemorate Napoleon’s victorious military campaign against the Austrians. The original portrait smacks of propaganda. Napoleon, in fact, did not pose for the original painting nor did he lead his troops over the mountains into Austria. He sent his soldiers ahead on foot and followed a few days later, riding on a mule.

Left: Detail of David’s signature on the horse’s breastplate, Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps or Bonaparte at the St Bernard Pass, 1800–01 version, oil on canvas, 261 x 221 cm (Chateau de Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison); right: Detail of Wiley’s signature on the horse’s breastplate, Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005, oil on canvas, 274.3 x 274.3 cm (Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York) © Kehinde Wiley

Detail of central figure, Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005, oil on canvas, 274.3 x 274.3 cm (Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York) © Kehinde Wiley

Choosing symbolic details

Wiley calls attention to ideas about authority and historical representation, keeping many original elements and making significant alterations. The royal blue coat of the original makes an appearance (peeking out from the young man’s camouflage shirt), as does the gold-encased sword (held in place by a red strap). But Wiley’s subject wears an outfit that is completely contemporary and reflective of a culture notorious for flashy imagery and larger than life figures: hip hop culture. This young man wears camouflage fatigues, Timberland work boots, and a bandana—conjuring up militaristic associations with the original painting and with the violence of contemporary urban America, particularly as experienced by young Black men. The subject of Wiley’s painting reveals his tattoos and wears red wristbands from the Starter sportswear company, details that add to the sense that this is a real individual living in the early 21st century.

Instead of the naturalistic setting of David’s painting, Wiley has inserted a decorative, unrealistic backdrop reminiscent of luxurious French fabric. This background, along with the high-keyed colors, and ornate frame (complete with faux family shields and the artist’s self-portrait at the top) call attention to the artificiality and pompousness of image-making.

Detail of sperm, Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005, oil on canvas, 274.3 x 274.3 cm (Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York; photo: Gayle Clemans) © Kehinde Wiley

The background is also infused with tiny paintings of sperm—Wiley’s way of poking fun at the highly charged masculinity and propagation of gendered identity that are involved in the Western tradition of portraiture. This particular subgenre of portraiture—the equestrian portrait—is particularly infused with the lineage of male power. From classical Rome to post-revolutionary France, political and military leaders on horseback have evoked and perpetuated social norms of masculine might and control (for example, this equestrian portrait of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius).

Through his demonstration of extraordinary painting skill and his use of famous portraits, Wiley could be seen as wryly placing himself in line with the history of great master painters. Here, for example, he has signed and dated the painting just as David did, painting his name and the date in Roman numerals onto the band around the horse’s chest. Wiley makes another reference to lineage in the foreground where he retains the original painting’s rocky surface and the carved names of illustrious leaders who led troops over the Alps: NAPOLEON, HANNIBAL, and KAROLUS MAGNUS (Charlemagne). But Wiley also includes the name WILLIAMS—another insistence on including ordinary people of color who are often left out of systems of representation and glorification. Not only is Williams a common African-American surname, it hints at the imposition of Anglo names on Black people who were brought by force from Africa and stripped of their own histories.

Left: Detail of inscription reading “Bonaparte,” Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps or Bonaparte at the St Bernard Pass, 1800–01 version, oil on canvas, 261 x 221 cm (Chateau de Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison); right: Detail of inscription reading “Williams” and Bonaparte,” Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005, oil on canvas, 274.3 x 274.3 cm (Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York) © Kehinde Wiley

About the artist

Kehinde Wiley attracted media and art world attention almost immediately after earning his MFA from Yale University in 2001. He was an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem and has been included in many significant group and solo exhibitions. Wiley now employs studio assistants who participate in his “street-casting” process and in the various stages of painting and sculpture fabrication. In addition to large-scale paintings, Wiley has created stained glass, painted altarpieces, and cast bronze sculptures, all of which examine of art history, race, gender, and the power of representation.

Additional resources

Read about this artwork in the Reframing Art History chapter “Responding to the early modern European tradition.”

Shahrazad A. Shareef, “The Power of Decor: Kehinde Wiley’s Interventions into the Construction of Black Masculine Identity” (UMI Dissertations Publishing, 2010).

Eugenie Tsai, ed., Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic (Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Museum, 2015).