Stiching a Nakshi Kantha (embroidered quilt), Bangladesh (photo: Faizul Latif Chowdhury, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Textile traditions of the Indian subcontinent potently capture the daily lives, rituals, and practices of individuals and communities, often serving as sites for expressions of identity and agency. We see this prominently in the context of embroidery practices such as:

- Kantha embroidery of Bengal (present-day West Bengal and Bangladesh)

- Kutch embroidery of Sindh, Rajasthan, and Gujarat (present-day India and Pakistan)

- Phulkari embroidery of Punjab (present-day India and Pakistan)

These traditions, which have been predominantly practiced within homes in a non-commercialized context, are inherently intimate and personal, reflecting the rich inner world of those who typically engage with them. Through their bright color palettes and unique visual vocabularies, these embroideries evoke memories and become containers of self-expression as well as carriers of their community’s stories.

Appliqué fabric coverlet showing women churning butter and carrying pots of water, 20th century (Gujarat, India), cotton, 195 x 117 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Embroidery and community

For women of several communities, embroidery has been an important aspect of their daily life. In Kutch, after completing their household chores, they would typically gather in common spaces such as courtyards and balconies each afternoon to work on their embroidery. This was culturally considered a form of relaxation and leisure. This practice also fostered friendships and a sense of communal belonging among the women. Younger generations would be inducted into the practice in these sessions, where they would learn by observing their elders. The design vocabulary of these embroidery practices reflects these intimate interpersonal and community relationships. For instance, the central motif on this appliquéd fabric coverlet depicts two women churning butter, and the motifs on either side show women carrying pots of water. The pastoral nature of communities in Kutch makes the production and consumption of dairy and related products central to their lives. The arid region also often faces a scarcity of water, making fetching water from wells an important activity that women undertake everyday.

Social rituals around Phulkari embroidery in pre-colonial Punjab were quite similar to the embroidery practices of Kutch. After completing their work in the fields, women in Punjab would also assemble in courtyards before their evening household chores to embroider colorful shawls. The intergenerational nature of the Phulkari tradition further cemented its importance within community life in the region. Although embroidery was similarly a communal practice in Bengal, there was a decidedly individual aspect to it as well. Women here would often stay up late into the night, embroidering Kanthas by candlelight and working in silence. This solitary pursuit created a sense of deep attachment to the age-old practice as they etched innumerable stories and memories onto the fabric.

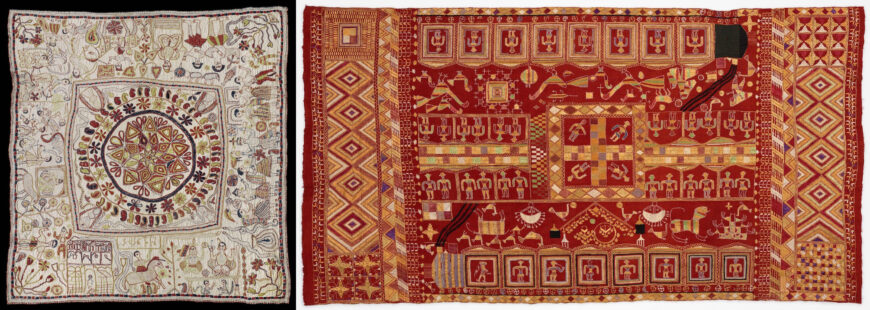

Left: Kantha with snake goddess Manasa, 1875 (Undivided Bengal), cotton, satin, 79.4 x 73.7 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art); right: Sainchi Phulkari (shawl) with train design, 20th century (Punjab), cotton, silk, 227.3 x 123.2 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Embroidery and identity

Embroidered textiles offer a unique insight into the private and undocumented lives of women. In 19th-century Bengal, Kantha embroidery was also a form of catharsis. The practice not only provided an escape from the political uncertainty of the times, but also served as a canvas for the expression of the makers’ inner turmoil. One can find themes of love, separation, and devotion in embroidered Kantha pieces. These textiles can be read as narratives of their hopes and dreams, their fears and aspirations, stitched onto fabric. For instance, the bottom panel of one Kantha has folk narratives of the snake goddess Manasa etched onto its surface. The story deals with the grief of losing one’s husband to a venomous snakebite and emphasizes the importance of women’s piety, devotion, and sacrifice in ensuring the wellbeing of her husband. The design vocabulary of the Phulkari tradition also deals with similar themes of love, loss, and longing. This shawl depicts large trains with passengers, emitting black smoke, embroidered on either side. Trains are commonly read as symbols of longing for husbands and sons working in faraway towns or daughters married off far from home.

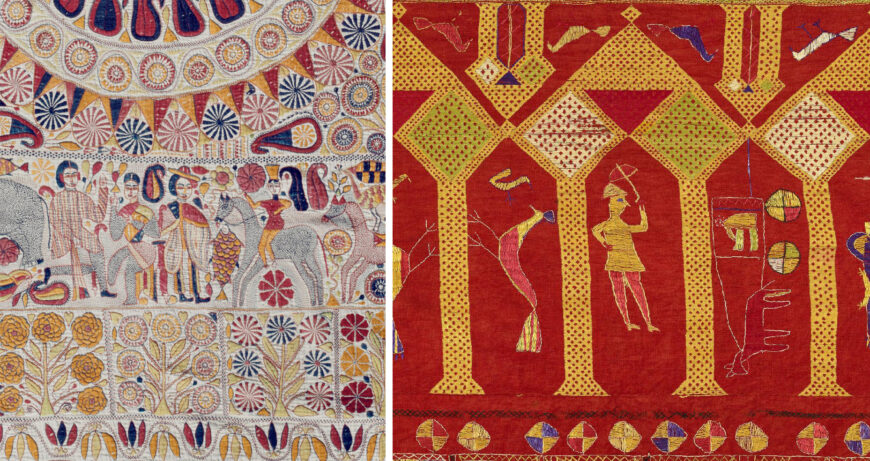

Left: Bengali “gentlemen” wearing round-brimmed hats, laced shoes, and jackets (detail), Kantha, late 19th century (Undivided Bengal), cotton, satin, 194.3 x 116.8 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art); right: colonial figure with a parasol and a helmet (detail), Darshan Dwar Phulkari, first half of the 20th century (Punjab), cotton, silk, 243.8 x 139.1 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Beyond representing home and the interior, embroidery traditions such as Kantha and Phulkari are also documents of changing social life under British colonial rule in India in the 19th and 20th centuries. This Kantha, for instance, depicts a new class of English-educated Bengali “gentlemen” with a penchant for Western aesthetics and tastes. The figures wear European costumes such as round-brimmed hats, laced shoes, and jackets. The Darshan Dwar Phulkari also depicts a colonial figure with a parasol and a helmet—an insight into the pervasive presence of colonial rule in Punjab.

In addition to serving as expressions of personal identity, these textiles also carry a sense of communal pride within their folds. In Kutch, women continue to use specific motifs that have evolved to become markers of caste identity. Motifs have also historically been used to narrate stories that reflect social and political circumstances. A prominent example can be seen in the embroidery of the Rabaris in Kutch, where stylistic motifs such as elephants were replaced with more contemporary motifs such as cupboards—symbols of settlement and wealth—as members of the community moved away from their caste-assigned profession of camel herding to more settled forms of living.

Vari Da Bagh Phulkari, c. 1930 (Undivided Punjab), cotton, floss, silk, 238 x 126 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Chope Phulkari, 20th century (Punjab), cotton, floss, silk, 282 x 181 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Kinship-based exchanges

Kantha, Kutch, and Phulkari embroidery pieces were traditionally made to be circulated within families and communities in the form of heirlooms, for use in dowry, and other gifting practices. Such kinship-based exchanges tethered these textiles to communal identities. Coveted as family heirlooms, Kantha pieces often carry stains on their surface and have a distinctive smell that evokes memories of family recipes and the comfort of domestic life. In addition to inducing multisensorial experiences, these textiles also serve as a medium of intergenerational communication, as family elders embroider pieces for their children and grandchildren. In Punjab, women often start embroidering a Vari da Bagh Phulkari shawl to mark the birth of their grandson. This is a rite of passage, as these shawls are made to be gifted to the grandson’s future bride on his wedding day. The bride’s grandmother embroiders a Chope Phulkari shawl characterized by yellow triangular motifs on a red base. This is used to wrap the bride after a ritual bath, an important pre-wedding ceremony in the region.

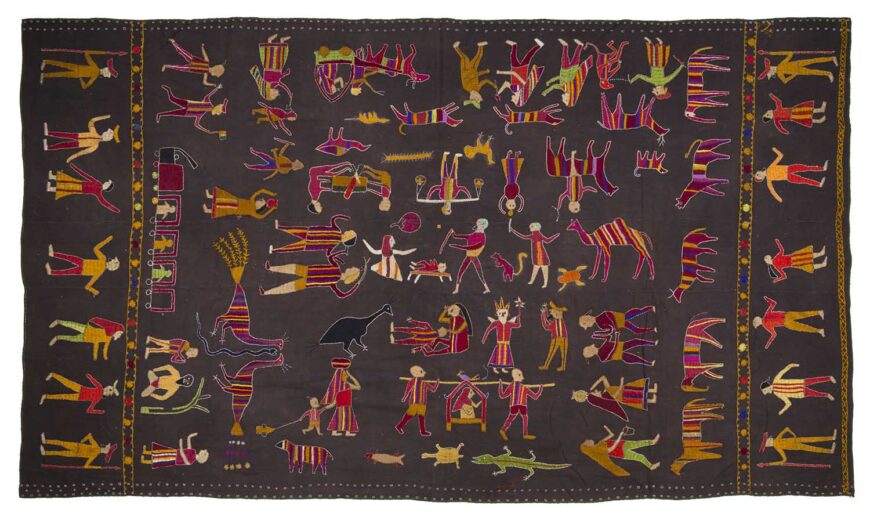

Sainchi Phulkari, early 20th century (Undivided Punjab, India), cotton, floss, silk, 214 x 120 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Embroidered Kothalo (dowry bag), 20th century (Gujarat, India and Sindh, Pakistan), cotton, mirrors, sequins, and glass, 21.5 x 15 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

In Kutch and Punjab, intricately embroidered pieces also form the bulk of a bride’s wedding trousseau. Sainchi Phulkari shawls that depict scenes of village life are popular dowry items in Punjab. In addition to several elaborate costumes, coverlets, and Torans that are included in a bride’s dowry in Kutch, it is common to see intricately embroidered dowry bags filled with items like cash, toiletries, and ornaments during the wedding. As a result, these practices evoke memories of occasions such as marriages and other rituals.

For several centuries, an extensive repository of embroidered textiles remained hidden within the homes of makers and was relatively unknown to the world. As these complex interior worlds of women are increasingly becoming open to our perusal and exploration, it is imperative we critically examine them while being respectful of their socio-cultural context and the emotional investments of the community.

Secondly, due to their associations with femininity and domesticity, embroidery practices are often invisibilized or treated as activities of “leisure” rather than as productive labor. Yet these traditions are time-consuming and require precision and skills. In fact, the women practicing consider them to be artistic endeavors, often even signing their names on pieces of embroidery.

In recent decades these embroidery practices have been commercialized, thereby changing their relationship with those who produce them in significant ways. While some women have begun incorporating machine-made materials such as sequins and other rickracks in their embroidery, several others do not engage in the tradition anymore. Despite such changes, these practices continue to remain embedded within communal relationships and serve as testaments to the rich and often undocumented private lives of their makers.

Additional resources

Take a short course on Textiles from the Indian Subcontinent with The MAP Academy

Eilund Edwards, Textile and Dress of Gujarat (London: V&A Publishing, 2011).

Judy Frater, Threads of Identity (Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 1995).

Judy Frater, “This is ours’: Rabari Tradition and Identity in a Changing World,” Nomadic Peoples, volume 6, number 2 (2002), pp. 156–69.

Pika Ghosh, Making Kanthas, Making Homes: Women at Work in Colonial Bengal (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2020).

Michelle Maskiell, “Embroidering the Past: Phulkari Textiles and Gendered Work as ‘Tradition’ and ‘Heritage’ in Colonial and Contemporary Punjab,” The Journal of Asian Studies, volume 58, number 2 (1999), pp. 361–88.

Darielle Mason, Kantha—The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection and the Stella Kramrisch Collection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

Darielle Mason, Phulkari—The Embroidered Textiles of Punjab from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017).

Niaz Zaman and Cathy Stevulak, “The Refining of a Domestic Art: Surayia Rahman,” Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings (2014).

Drawing from articles on The MAP Academy