View of the North Cemetery at Meroe (Sudan) showing several of the steep-sided pyramid tombs with their pylon-fronted chapels. Forty-one such royal tombs, belonging to both kings and queens, were constructed here between around 300 B.C.E. and 350 C.E. (photo: UNESCO)

Summary

After the cultural height and military might of the New Kingdom, the fractured Third Intermediate Period led to a loss of control over areas that had been Egyptian territories. Since power vacuums never last, there was an immediate rise in the Kushite culture to the south, which reestablished old cultural centers along major trade routes and utilized the Egyptian temple structures in Nubia to help legitimize their rule as kings of Egypt. Even though Egypt was largely unified for most of Dynasties 25, 26 and 28–30, the era referred to as the Late Period (c. 713–332 B.C.E.) was volatile and endured successive invasions and occupations by the Assyrians and the Persians.

Eventually, Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great of Macedon in 332 B.C.E. Alexander built his new capital at Alexandria on the Mediterranean Sea. The subsequent Ptolemaic Period saw a huge increase in settlers of Greek and Mediterranean origins, especially in the delta. Hellenistic influence was particularly strong at court and in elite circles, with Greek versions of local gods (like Serapis, who was derived from Osiris) holding sway. For the majority of the country, however, Egyptian traditions and art were largely unaffected. The Ptolemies presented themselves as pharaohs and were shown performing traditional cult rituals in the many massive temples constructed during this period.

When the Ptolemaic ruler Cleopatra VII was defeated by Octavian in 30 B.C.E., Egypt became a Roman province. Roman emperors continued to build Egyptian-style temples, with themselves depicted on the walls performing the same rituals as the kings that came before them. Egyptian-style temple constructions undertaken by Rome stopped during the second century C.E., as Rome’s own political instability rippled through the empire. Egyptian temples were ordered closed by the Byzantine emperor and the last known hieroglyphic inscription (at Philae) was carved in 394 C.E.

Late Period (c. 713–332 B.C.E.)

The kings of Egypt of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty came from Kush, a culture that had combined Nubian and Egyptian elements to create something unique. The chief religious site in Kush, the mountain of Gebel Barkal, sported temples of Amun-Ra and Hathor and royal inscriptions, such as on the victory stela of King Piye, are packed with references to Egyptian deities. While they established control as far north as Memphis, they focused more of their attention in the south. At Karnak, the powerful priestess known as the God’s Wife of Amun rose even further in eminence; these figures served as royal surrogates in Thebes for kings who ruled from another location. This role was often filled by princesses of Dynasties 25 and 26.

In the seventh century B.C.E., the Assyrians invaded Egypt down to Thebes and pushed the Nubian kings back to Kush. The Assyrians looted sacred sites, including the temples at Heliopolis and Karnak, stealing massive amounts of treasure. However, given the military needs of their empire elsewhere, they did not have the manpower to leave a large force in Egypt. Instead, they appointed Egyptian governors to collect their tribute. As soon as the Assyrians were otherwise occupied, a family from Sais in the delta region took over and ruled an independent Egypt as the Twenty-sixth Dynasty.

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty kings established themselves down to the southern border at Elephantine and north into Palestine. They increased their contacts with other Mediterranean powers, including treaties with Lydia, connections at Delphi, and actions on Cyprus. A significant Greek trading colony was founded at Naukratis and garrisons of Greek mercenaries helped protect the temples at Memphis.

The next few centuries saw an invasion and period of rule by the Persians, a subsequent brief period of Egyptian rule, followed by a second, more destructive, Persian invasion. In 332 B.C.E., the Persians were pushed out by Alexander the Great of Macedon. He was crowned king in the temple of Ptah at Memphis, declared himself a living god, and founded the city of Alexandria on the coast of the Mediterranean. After his death, Alexander’s generals divided his empire, with Egypt coming under the control of the Greek general, Ptolemy. This family would rule Egypt for the next 300 years.

Temple of Edfu, 237–57 BCE, Ptolemaic Period, sandstone, Edfu, Egypt (photo: Marc Ryckaert, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Ptolemaic (c. 332–30 B.C.E.) and Roman (c. 30 B.C.E.–395 C.E.)

During the Ptolemaic period, the country was ruled from the newly-established city of Alexandria. The structure of the government and administrative organization was aligned in accordance with Greek practices. Almost all important government posts were given to Greek settlers rather than native Egyptians. Although the Ptolemaic era was decidedly multi-cultural and multilingual, with significant Greek influence evident in many arenas, the ruling family readily identified themselves with Egyptian deities and encouraged the populace to view them as such. Many were crowned in the temple of Ptah at Memphis and they supported ancient religious cults. They also undertook a massive temple rebuilding program to help legitimize their rule. These temples were traditional Egyptian in style, both architecturally and in their decoration, although Greek flourishes are often discernible in the carving and there was a massive increase in the number of hieroglyphic signs used. Ptolemaic rulers had themselves depicted in relief performing the same duties before the divine as their native predecessors had been doing for millennia.

Ptolemaic kings were prolific builders and they constructed huge temples at Edfu, Esna, Dedera, Kom Ombo, and Philae, among others. Beyond the religious realm, King Ptolemy II founded the famous Library of Alexandria, which at its height contained around 700,000 scrolls. This king also completed the dazzling Pharos lighthouse; one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world.

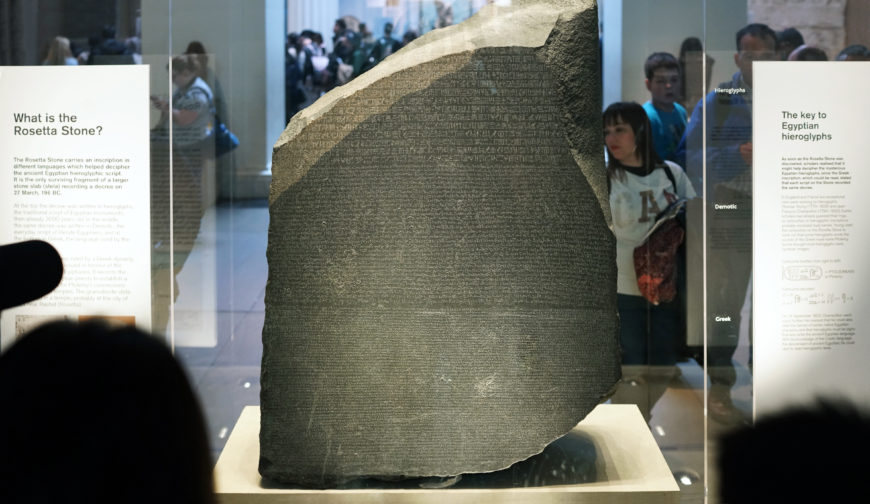

In 196 B.C.E. King Ptolemy V Epipanes issued a decree to establish his divine cult. This was carved onto a slab of granodiorite and was probably originally erected in a temple. Three versions of the same decree were engraved on the slab; two being in ancient Egyptian and one in Greek. Much later, the slab was removed and used as building material in a fort near Rosetta in the delta, where it was discovered by Napoleon’s expedition in 1799. Being a bilingual document with well-known Greek as one of the languages, the discovery of the Rosetta stone immediately began the race to translate the ancient Egyptian language.

Bust of Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator, c. 40–30 B.C.E., marble (Altes Museum, Berlin; photo: José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The last of the Ptolemaic rulers was Cleopatra VII, who allied herself first with Julius Caesar and then with Mark Anthony in an attempt to keep Egypt from being absorbed into the Roman Empire. In the end, she was unsuccessful and in 30 B.C.E. Egypt succumbed to the forces of Octavian, who subsequently became the first Roman emperor, Augustus. This was the end of Egypt’s independence and it became a Roman province.

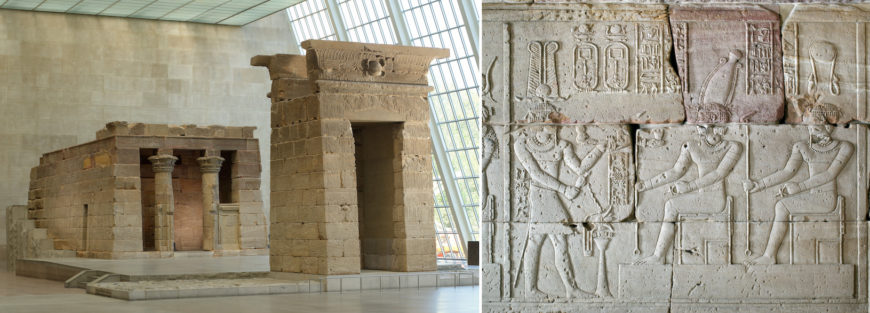

Left: The Temple of Dendur, completed by 10 B.C.E., Roman Period; right: detail: vignette on the interior south wall of the porch showing Augustus (left) burning incense in front of the deified figures of Pedesi and Pihor. Both: Egypt, Nubia, Dendur, West bank of the Nile River, 50 miles South of Aswan, Aeolian sandstone, Temple proper: H. 6.40 m (21 ft.); W. 6.40 m (21 ft.); L. 12.50 m (41 ft.) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

During the Roman period, Egypt was treated as a bread-basket and source of rich resources. Grain, papyrus, hard stones, statues, obelisks, and treasure of all kinds were removed to Rome and other locations in the empire.

Alexandria was a nexus of Greek culture and a major hub for trade routes into the desert and to the East. Several Roman emperors, including Augustus, Trajan, and Hadrian, constructed cult temples in Egypt and had themselves depicted in the same poses and ritual actions as the kings who ruled before them to help establish their legitimacy. There was a clear interest in the ancient wisdom of this mysterious and enigmatic land—Egypt was renowned throughout the empire as the realm of priest-magicians.

Mummy of Herakleides, 120–140 C.E., Romano-Egyptian, human and bird remains, linen, pigment, beeswax, and wood, created in Egypt (The Getty Villa; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Along the Nile, funerary beliefs remained largely unchanged though more focus was placed on the external embellishment of the body. Modern styles were added to the painted coffins and images that represented the deceased, with Greco-Roman hairstyles, jewelry, and dress appearing. Sensitive and haunting portraits of the dead, painted on wooden panels using encaustic (a luminescent wax-based paint that can be built up in many layers that creates a dazzling sense of depth) began to be inserted into the bandages over the face of the often elaborately wrapped body. Startling in their realism, they represent the culmination of the ancient Egyptian desire to ensure that the body was preserved and immediately identifiable.

The classic Egyptian language and hieroglyphs were only used for temple and ritual contexts by this point, however, Coptic emerged as a new written form of the Egyptian language and proliferated.

As political challenges arose during the second century C.E., less attention was directed at the provinces. Economic changes included an increase in the prominence of urban centers. In 392 C.E. Egyptian temples were ordered closed by the Christian emperor of Byzantium and the last known hieroglyphic inscription (at Philae) was carved in 394 C.E.

The Rosetta Stone, 196 B.C.E., Ptolemaic Period, 112.3 x 75.7 x 28.4 cm, Egypt © Trustees of the British Museum. Part of grey and pink granodiorite stela bearing priestly decree concerning Ptolemy V in three blocks of text: Hieroglyphic (14 lines), Demotic (32 lines) and Greek (53 lines).

In the fourth century C.E. pharaonic culture slowly came to an end as Christianity became the dominant religion in the Empire. Christianity arrived in Egypt early in the first century C.E., anchored in the flourishing Jewish community in Alexandria. Said to have been martyred in Alexandria in 66 C.E., Saint Mark was referred to as the first bishop of the city, which became a leading intellectual center of the Christian Church. Because it was protected by Nubian tribes who honored the goddess Isis, the last operating cult temple in Egypt was that of Isis at Philae on Egypt’s southern border. It closed in the sixth century C.E. From this point on, no one was left who could read the ancient texts and knowledge of the gods, their myths, and the written history of Egypt itself slipped into shadow until hieroglyphs were deciphered again in the 1800s using what is now known as the Rosetta Stone.

Despite the fact that pharaonic Egypt came to an end in the late imperial Roman period, Egypt’s influence continues. For instance, Egyptian monuments, such as obelisks, sphinxes, and other statues that were erected in Rome and elsewhere created a legacy of wonder that helped spark the Italian Renaissance and persists even today. Ancient authors consistently refer to Egypt as an influential ancestor and a source for aspects of Greek and Roman culture, a concept that likely impacted many artists and scholars over the centuries. It may be surprising to learn that mummification was practiced in Egypt as late as the seventh century C.E., even among Christians, and many ancient Egyptian traditions and rituals live on still today in Coptic Christianity and local Islamic practices. Revivals of Egyptian style in architecture, design, jewelry, furniture, and dress have accompanied every major discovery since Napoleon’s expeditions of 1798, especially the spectacular discovery of the tomb of king Tutankhamun in 1922. Egypt’s draw is undeniable and its mysteries eternal; the more you learn about Egypt, the more you realize how much you really don’t know . . . and the rabbit hole never ends.

| Period | Dates |

| Predynastic | c. 5000–3000 B.C.E. |

| Early Dynastic | c. 3000–2686 B.C.E. |

| Old Kingdom (the ‘pyramid age’) | c. 2686–2150 B.C.E. |

| First Intermedia Period | c. 2150–2030 B.C.E. |

| Middle Kingdom | c. 2030–1640 B.C.E. |

| Second Intermediate Period

(Northern Delta region ruled by Asiatics) |

c. 1640–1540 B.C.E. |

| New Kingdom | c. 1550–1070 B.C.E. |

| Third Intermediate Period | c. 1070–713 B.C.E. |

| Late Period

(a series of rulers from foreign dynasties, including Nubian, Libyan, and Persian rulers) |

c. 713–332 B.C.E. |

| Ptolemaic Period

(ruled by Greco-Romans) |

c. 332–30 B.C.E. |

| Roman Period | c. 30 B.C.E.–395 C.E. |

Additional resources:

Read an overview of Egyptian chronology and historical framework

Predynastic and Early Dynastic

Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period