Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt; it covers an area of approximately 8,000 square meters, and measures approximately 65 x 150 m and 65m high (on the north side). The mosque of Al-Rifa’i, built 1869–1912, is to the right (photo: Mariam Mohamed Kamal, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Described by a 15th-century observer as a building with “no equivalent in the whole world,”[1] the mosque-madrasa-funerary complex of the Mamluk Sultan Hasan in Cairo has been considered one of the greatest mosque complexes ever built since its construction in the 14th century. It includes a mosque, a madrasa (school), a mausoleum, and other buildings—all within the same space. A complex like this one was typically designed as one structure and sponsored by one patron. If the building has a tomb within, as this one does, it will also be referred to as a “funerary complex.” It stands today as one of the most imposing mosque complexes in Cairo. The complex is a quintessential Mamluk building type, especially in Cairo. It was the first building to combine a madrasa and congregational mosque together in the Islamic world, and it set a new standard in Mamluk Cairo.

The complex was built during a period of crisis between 1350 and 1380, when plagues, Nile floods, and famine all undermined political stability. This complex of buildings was a means for Sultan Hasan—a young and weak ruler—to express his power and piety. Although the complex was never completed and Sultan Hasan was not buried here, it is a famous examples of the many funerary complexes that the Mamluk sultans erected.

Location of the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan, Maydan Rumayla, and Citadel, Cairo (underlying map © Google)

The site

The Sultan Hasan complex is one of the largest buildings in all of Cairo. It faces directly onto a large maydan (public square) formerly called Maydan Rumayla (commonly known today as Maydan Salah al-Din) that was of central importance to Mamluk ceremonial rituals because it occupied the space just below the citadel, royal residences and military barracks that were the real, as well as symbolic, source of power and authority in Cairo. The complex was also very close to the location of the hippodrome and the famous horse market (that no longer survive), which played a key role in Mamluk military pursuits because, above all else, they were the most effective cavalry warriors since the Mongols.

Plan and design

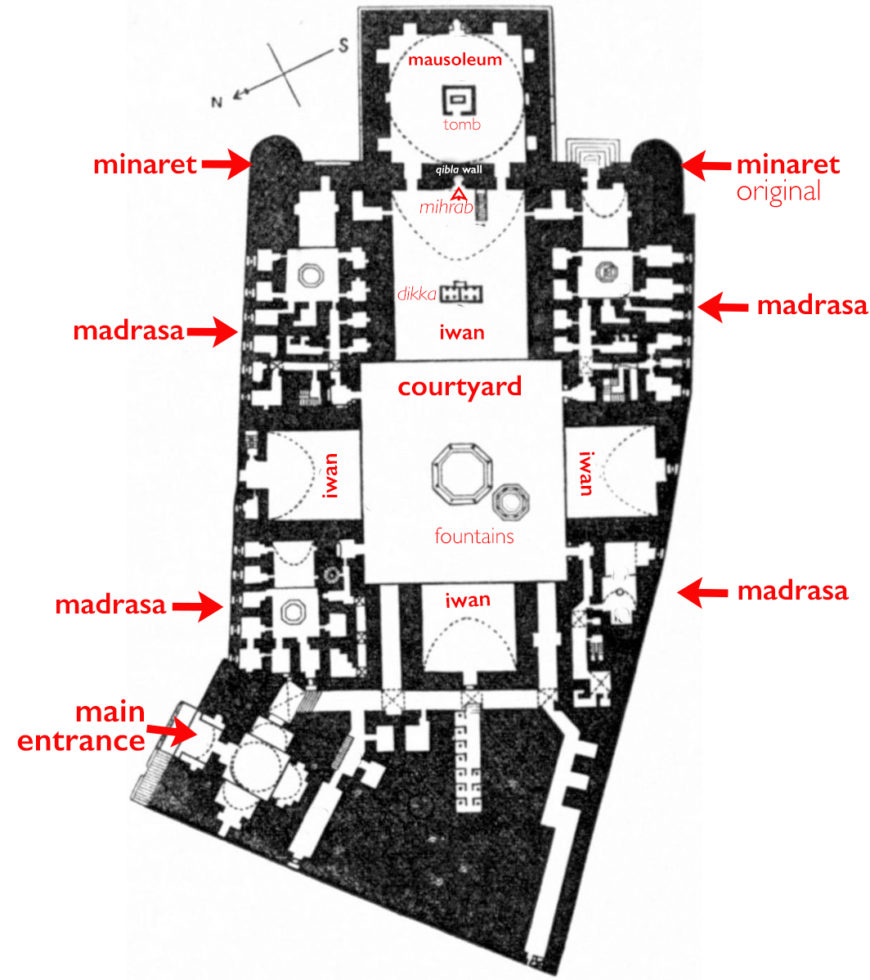

Although we do not have the name of someone considered an “architect” we do know the name of the “supervisor of construction,” an emir named Muhammad Ibn Baylik al-Muhsini, whose name is inscribed on a text band on the interior of the mosque. The complex is composed of a four-iwan jami‘ masjid (Friday Mosque), a madrasa (secondary school or college), and a qubba, or mausoleum. In this organization, the congregational mosque was composed of a central courtyard (sahn) with four iwans—halls enclosed on three sides and open to the courtyard on the fourth—on each side. When not in use for prayer, these spaces functioned as seminar meeting spaces for the madrasa.

Plan of the madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt; it covers an area of approximately 8,000 square meters, and measures approximately 65 x 150m (on the north side) and 65m high

The square space adjacent to the mosque is the mausoleum, and most of the rest of the building is dedicated to the madrasa and other support functions. The madrasa is also one of the largest in Cairo and contains four separate schools of Sunni Islamic law (each of which fits within the corner spaces around the central courtyard) faced by four unequal sized iwans, of which the southeastern was the largest because it is the direction of Mecca (known as the qibla iwan).

Courtyard with fountains, surrounded by iwans, in the madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Mohammed Moussa, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the decades up to and after the sack of Baghdad in 1248, the Caliph’s power had diminished, so the Mamluk Sultan and various other strong men vied for power across the Islamic World. The fact that the building contained all four major Islamic schools of law underscored the strong relationship between the Mamluk Sultan and the Caliph, who had become a figurehead by this time.

The building’s waqf, or endowment document, has survived partially intact and tells us about the complex’s buildings and how they were used and staffed. The waqf explains that in addition to the mosque, madrasa, and mausoleum, the complex was also to contain spaces for physicians to service the community and a sabil-kuttab (public water fountain dispensary and primary school for boys). In all the waqf stipulated that there should be accommodations for over 500 (madrasa) students, 200 school boys, and 340 staff members in all making it the largest of its day. [2]

Main entrance, Plan of the madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Djehouty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The decoration and design

The entrance portal and vestibule, and courtyard with iwans

Muqarnas above the main entrance portal, Plan of the madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Ahmed Al.Badawy, CC BY-SA 2.0)

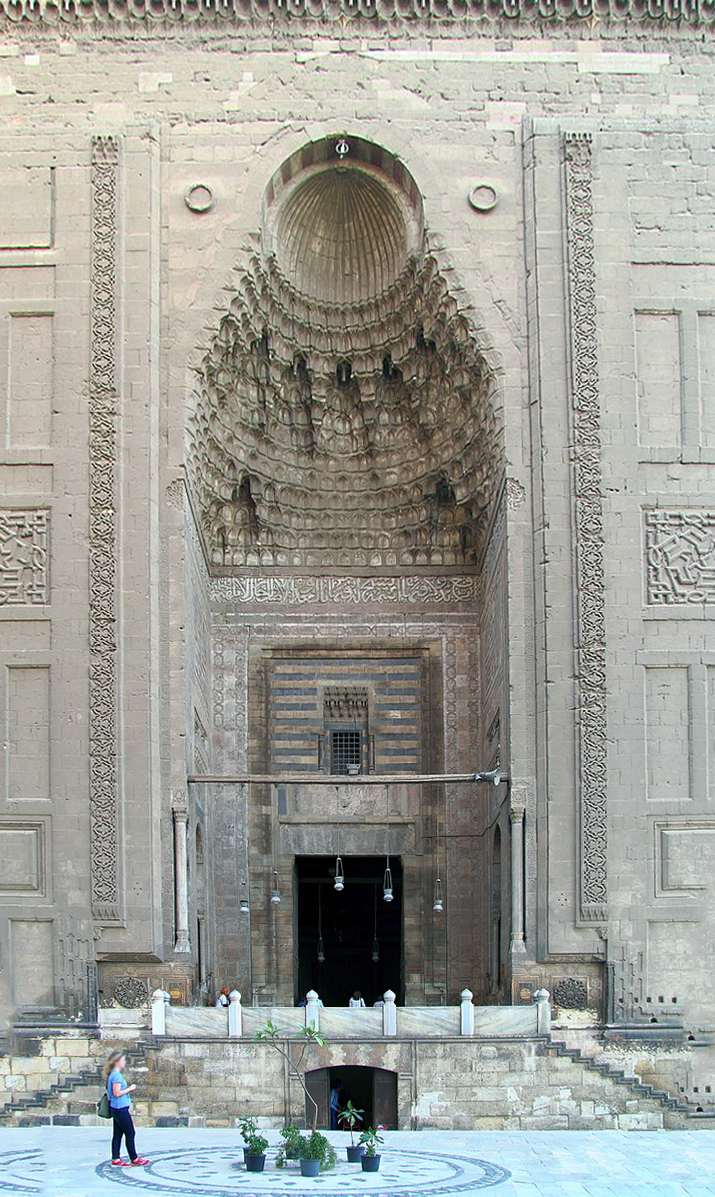

The exterior of the complex is stone, and the interior is mostly brick with stucco decoration. Due to the exterior’s vast surface, most decorative carving occurs near the entry portal and the elevation of the mausoleum facing onto the maydan (public square). One enters the complex through an enormous portal—the largest in Cairo—which is capped by an enormous hood filled with muqarnas (carved stalactite-shaped decoration).

The entrance portal

Decorative panels, main entrance, Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Djehouty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Both sides of the portal have highly refined stone carvings, including spiral cut columns to exaggerate their height, panels with interlacing geometric patterns, carved arabesques (intertwining and scrolling vines), and even Chinese decorative motifs. Chinese designs were transmitted, alongside with Chinese goods, on the silk roads, especially after the peace treaty signed between the Mamluks and Mongols in 1322, and would later make their way into Ottoman ceramics too.

Entrance vestibule, madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Michal Huniewicz, CC BY-SA 4.0)

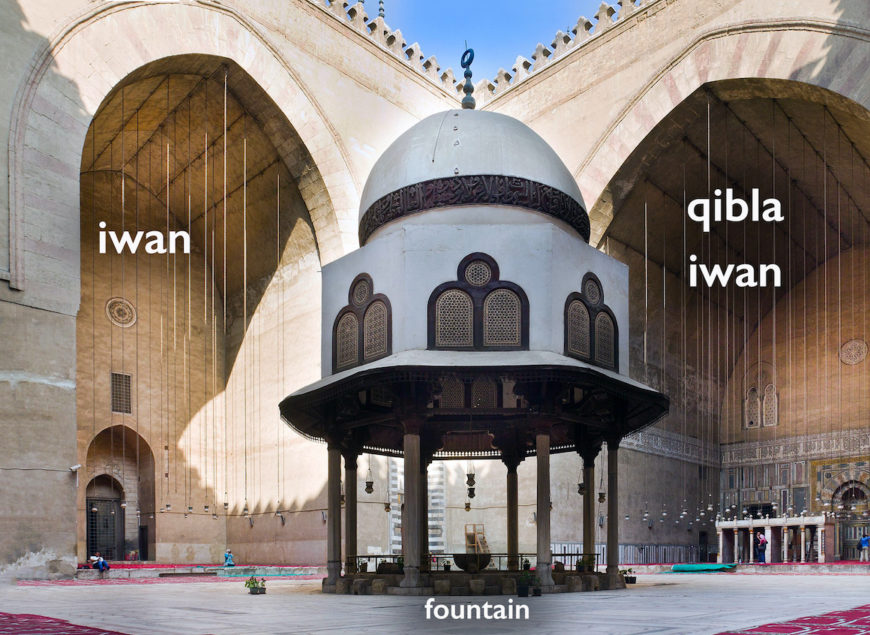

After passing through the entrance, you then enter a vestibule that allows you to either enter the mosque or other areas of the complex. Entering the mosque, you are confronted with the vast and grand open paved courtyard with four large iwans facing onto it and a large domed ablution fountain in the center.

The courtyard (sahn) with a fountain, surrounded by the four iwan

The main or qibla iwan

Qibla iwan, Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Mustafa Shorbaji, CC BY-SA 4.0)

According to contemporary chroniclers, Sultan Hasan ordered the main iwan with the qibla (a wall indicating the direction of Mecca) to be “five cubits wider” than the greatest known arch in the world at the time: the famous Sasanian Taq-i Kisra in Ctesiphon from centuries earlier. While the arch was not, in fact, bigger, this detail reveals something about Sultan Hasan’s global ambitions.

Qibla wall in an iwan, Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Berthold Werner, CC BY 3.0)

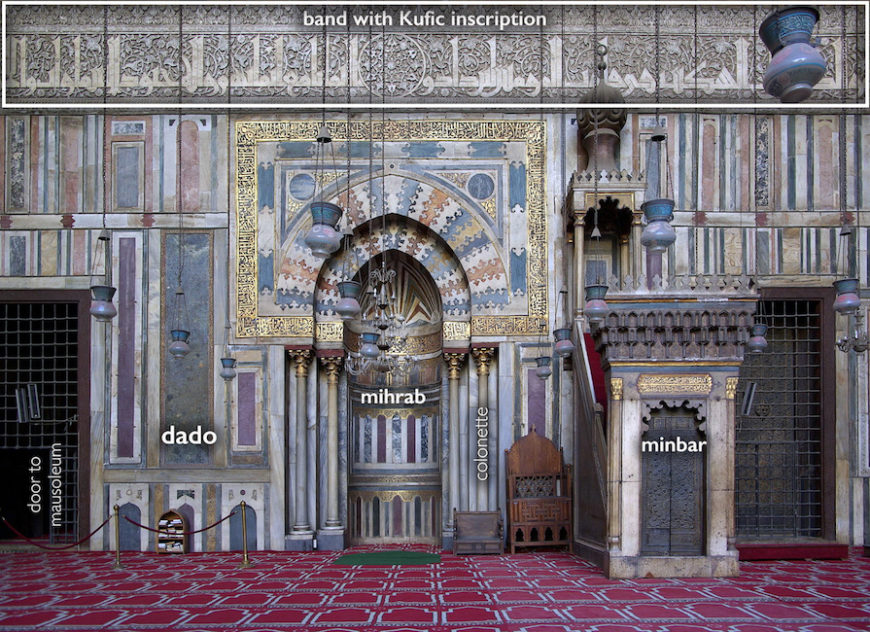

The main iwan is by far the most elaborately decorated due to its association with Mecca. The qibla wall within it is articulated with a rich marble paneled dado, and a large and unique stucco text band in Kufic letters above that wraps around the entire iwan.

The mihrab niche (also indicating the direction of Mecca) is given special treatment with a pointed arch, stone ablaq (alternating color stone), and is flanked by Gothic style colonettes, which were included due to exchanges with the Crusader kingdoms in and around Jerusalem. On either side are doors (one original bronze remains) that lead into the mausoleum directly behind the qibla wall. There is also a marble minbar (pulpit with steps) from which the sermon would be preached.

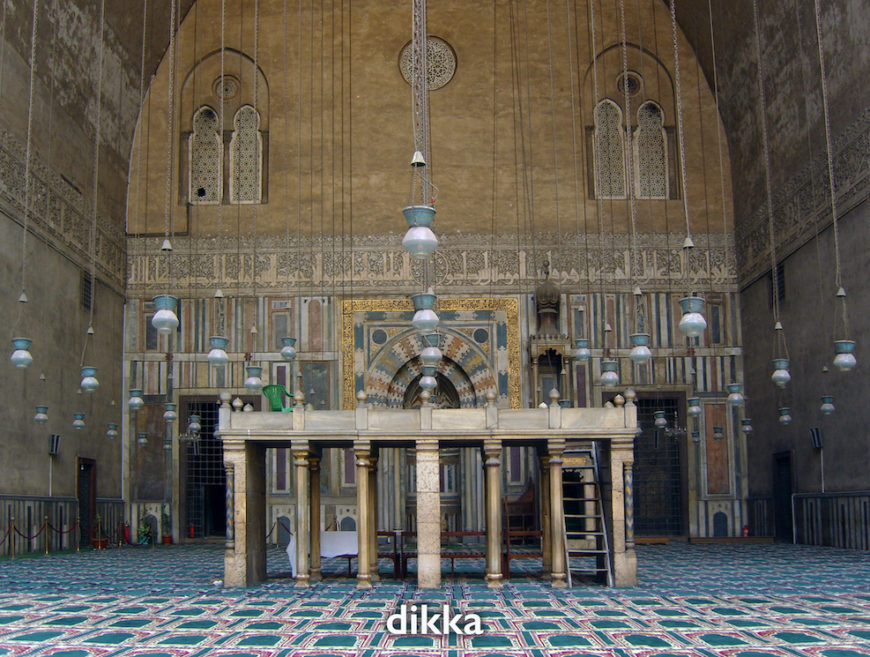

Dikka in a the qibla iwan, madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Effeietsanders, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In front of the iwan, almost in the main courtyard area, stands the dikka—a large raised platform carved out of marble that allows individuals to loudly repeat the prayer so those in the back can hear it. The iwans also had approximately 155 oil lamps hung from their ceilings at the same height above the ground, which, at night, would have illuminated the mosque in a magical way.

The qibla iwan

The mausoleum

Mausoleum, madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Baldiri, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The mausoleum—Sultan Hasan’s intended eternal resting place—is immediately behind the qibla wall with the mihrab, which represents a significant shift in planning and symbolism; this organization did not happen prior to the Mamluks. Placing a mausoleum directly behind the qibla wall has the—likely intended—result of hundreds of people praying in the direction of the tomb. If that were not enough, the waqf actually stipulates that there would be 160 full-time hafiz (men who were tasked with reciting the Qur’an out loud) placed in the various deep window sills around the mausoleum reciting the Qur’an at all hours of the day such that passers-by are reminded of the sacred gifts the sultan bestowed on the city in the form of this religious complex.

Famed minarets

Minaret of the Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Djehouty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

On the exterior, an unprecedented four minarets were ordered for the complex including two flanking the portal and two flanking the dome on the outer corners of the mausoleum on the maydan (public square). Out of the four giant minarets, only three were constructed and two of those collapsed; the first while Sultan Hasan was still alive in 1361 killing roughly three hundred people, mostly children attending the kuttab (primary school). The collapse was seen as a bad omen and the sultan was murdered a month later. Another minaret collapsed in 1671 while the mosque was full of worshipers, but luckily it fell away from the crowd. The only original remaining minaret is on the south-east corner of the mausoleum and reaches a staggering height of approximately 84 meters above street level.

The minarets of the Mosque of Sultan Hasan are famous for initiating the famous three-tiered minarets—a signature of Mamluk religious architecture—for which the city of Cairo is famous. In the Sultan Hassan mosque, the first several stories of the surviving minaret are integrated into the wall of the complex. Above that the minaret’s base is square until, further up it transitions into an octagon with small balconies on every other face. A larger balcony with muqarnas separates the middle tier, which is also octagonal, but significantly truncated and without decoration. The top balcony is articulated with muqarnas, upon which an open colonnade pavilion is capped with another ring of muqarnas that transitions to a tapered stone bulb. This example was to be emulated and refined throughout the rest of the Mamluk period, forever defining Cairo’s iconic skyline.

World famous mosque

Although Sultan Hassan was murdered by one of his own Mamluks, construction of the mosque continued after the Sultan’s death, but was never completed. His body was never recovered nor entombed in this mosque. During his short reign, he managed to restore the mosque of al-Hakim in Cairo and monuments in Mecca, establish a madrasa in Jerusalem, build a lavish palace in the citadel in Cairo, construct a mausoleum for his wife and one for his mother, build several sabil-kuttabs (school and water dispensary), and founded one of the most famous mosques in the world. Clearly, architecture was a way he could express his ambitions. The building remains one of the most ingeniously designed mosques in the history of Islamic architecture; no other Mamluk monument displays as many innovations as this single building.