Sculptural ceramic ceremonial vessel that represents a dog, c. 100-800 C.E., Moche, Peru, 180 mm high (Museo Larco). This spotted dog is represented in several scenes of Moche art accompanying Ai Apaec, the Moche mythological hero.

A Complex Culture

Moche architects and artists raised spectacular adobe platforms and pyramids, and created exquisite ceramics and jewelry. Their art, unlike that of most Andean cultures, is naturalistic and rich in imagery, inviting us to explore their world.

The Moche culture thrived on Peru’s northern coast between approximately 200 and 900 C.E. Rising and falling long before the Inka, the culture left no written records, and the early Spanish colonists who chronicled the cultures of Peru found the Chimú people in what had earlier been Moche territory. The Moche are a prime example of how archaeologists and art historians use scientific methods of data collection and evaluation in understanding ancient, non-literate cultures.

In the early 20th century, there was very little scientific excavation in Peru. Many art objects that came into museums and private collections were taken from graves and had no record of their original context. Based on this limited knowledge, scholars thought that the Moche had been a unified state that held sway over a large swath of the north coast, from near the border with modern-day Ecuador in the north to the Huarmey river valley to the south (Huarmey is approximately 180 miles north of the modern capital city of Lima). This conclusion was based on the similarity of ceramic and metal artworks being found throughout the range.

Not a single unified political entity

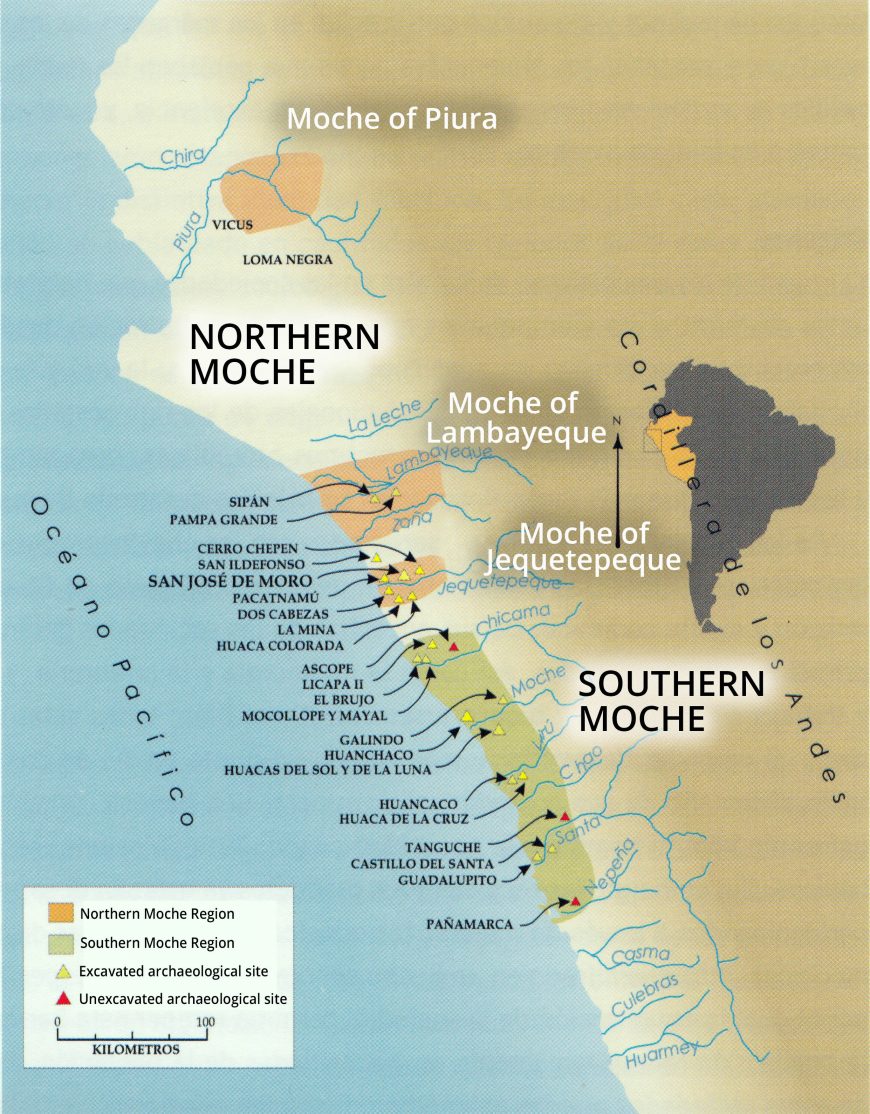

As modern scientific archaeology began in the area, it became clear that the Moche were not a single, unified political entity. Archaeologists and art historians began to see that differences in style and iconography could be determined between areas. Architectural structures were different at different sites. In addition, carbon dating allowed scholars to understand that some styles of pottery could be from one time frame in one river valley, while being associated with a completely different time frame in another. As more data was accumulated, hypotheses were tested and the conception of the Moche was revised and reassessed. What emerged was a vision of the Moche as politically independent groups who shared a common ideology, mythical and religious beliefs and practices, as well as a common iconography for their artwork.

Independent areas (sometimes as large as a pair of river valleys, sometimes as small as one section of a single valley) would signal that they belonged to Moche culture by using Moche themes in their artwork, while at the same time asserting differences—in architecture, in iconographic style, and in which figures from the mythology were deemed important. In this way, separate Moche polities could express both their political independence as well as their sense of belonging to a larger cultural system. The biggest separation of Moche style and iconography splits them into northern and southern areas (see map above), which can then be subdivided into smaller, politically independent areas.

Ceramic artist Walter Acosta showing a replica Moche mold.

Mold-made replicas in ceramic artist Walter Acosta’s workshop, painted with slip and ready to be fired.

North-South Differences

The Southern Moche tended to be expert ceramicists—producing a large amount of fine, thin-walled vessels painted in slip. Moche artists used only three colors—cream, red-brown or red-orange, and black to decorate their ceramics. Many Moche ceramics were made using molds, and so we have many duplicate pieces. The ability to control imagery through the use of molds seems to have been important to the political elites of the Moche.

Early Moche vessels are very sculptural, depicting humans, supernatural figures, animals, and plants in a great variety. Later Moche ceramics feature complex line drawings of similar subject matter (called fineline style). The Moche often used a distinctive spout on their vessels, called a stirrup spout. It is composed of a hollow tube of clay bent into an upside-down U shape, with another tube piercing it at the apex of the curve (see images below). This spout form has ancient origins in the Andes, and it seems possible that the Moche deliberately chose this form to echo its use in during the earlier Cupisnique (1500-500 B.C.E.) and Chavín (900-200 B.C.E.) cultures. Fine ceramics would have been used as gifts from the highest elites to the lower elites and middle classes, helping to cement the social bonds that supported the power that the elites held. Fine ceramics have been found in households, and the pieces in graves show evidence that they had been used.

Left: Fox Warrior Bottle, c. 4th – 6th century C.E., Moche, Peru, ceramic, 26.7 cm; and right: Fox Warrior Bottle, 7th-8th century C.E., Moche. Peru, ceramic, 29.46 cm (both, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Northern Moche are celebrated for their metalwork, especially the exquisite pieces found in the tombs of Sipán in the Lambayeque valley. Working in gold and silver, Moche artists were adept at hammering, soldering, and setting stones, as well as developing a process to make a copper-gold alloy appear to be solid gold—a technique known as depletion gilding. Gold, silver, semiprecious stones and Spondylus shell were used to make the elaborate regalia of the highest elites. Massive necklaces and bracelets, ear spools, headdresses, nose ornaments, and more were made by Moche artists for the great lords. While there certainly were skilled ceramicists in the north and able metalsmiths in the south, the general division of materials between these two areas helps define some of their differences. Both areas also would have had weavers producing fine textiles, but few examples have survived.

Nose Ornament with Intertwined Serpents, Moche, Peru, c. 390-450, gold, silver, shell, 12.5 x 21.1 x 1.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Iconography, Ideology, and Human Sacrifice

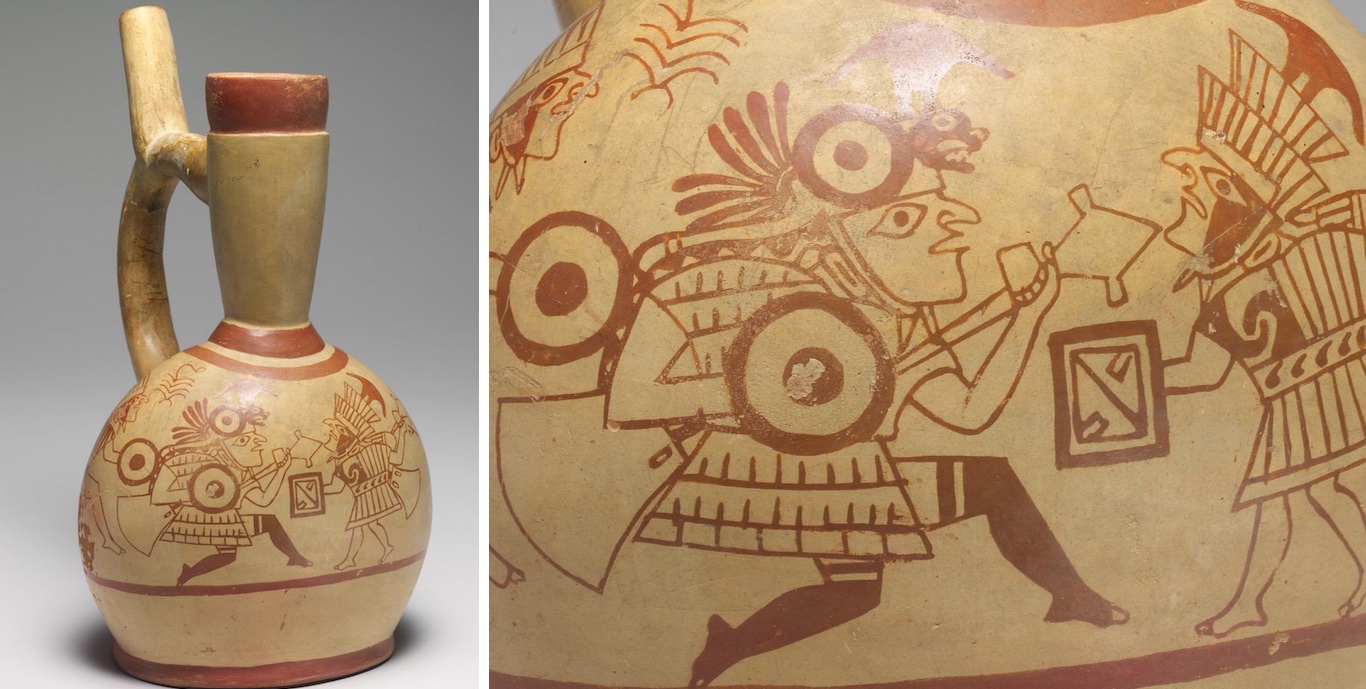

Early scholars assumed that armed conquest was the mechanism of power for the Moche state and Moche art certainly has a great deal of imagery relating to armed combat. However, it now appears that only some Moche expansion was due to military action. Other areas seem to have simply been colonized in uninhabited areas, or Moche culture was adopted by local elites who were impressed by the ideology. The imagery of combat is, in large part, related to that ideology, but not as a call to conquest. Instead, it seems that a lot of Moche combat imagery has ritual meaning. It focuses on hand-to-hand combat between two individuals, using cone-headed clubs as weapons and small shields for defense. Interestingly, this ignores what we know archaeologically about Moche warfare—which included the use of spears and darts propelled by throwing sticks, as well as slings used to propel stones with astonishing force. The Moche artwork, in other words, tells us one thing about their culture but omits other things. We can think of this as a form of propaganda—emphasizing the ritual aspects of Moche elite power rather than the more practical aspects of war. Moche art and archaeology also tell us what the point of this hand-to-hand combat was.

Warrior Bottle, 4th-7th century, Moche, Peru, ceramic, 28.6 x 17.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the art, we see victorious warriors knocking the helmet off of their foe, sometimes bloodying their nose in the process. The defeated warrior is then stripped of his armor and clothing. With a rope tied around his neck, he is led by the victor, who carries the armor and clothing in a bundle to signify his victory. The defeated warriors are eventually sacrificed in an elaborate ritual, their necks sliced and blood collected, to be drunk by figures that are dressed in the costumes of gods.

Archaeologists have uncovered three sets of sacrificed prisoners at the site of Huaca de la Luna in the Moche river valley. These large-scale sacrifices took place at different times over the course of hundreds of years. The skeletons show signs of having undergone combat, as well as having had their throats slit. These remains seem to show that what is depicted in the art was also carried out in life (at least these three times). Whether smaller-scale sacrifices related to this imagery took place is still being investigated, at Huaca de la Luna and other large Moche sites. The continued archaeological exploration and analysis of Moche artworks will help researchers to further understand this complex culture.

Adobe mural depicting stripped prisoners led by ropes around their necks, Huaca El Brujo, Peru (photo: d.j. a., CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)