Southwest façade, Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, 999/1000 C.E. (photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0)

On the northern fringes of Toledo, Spain, the small Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm tells a compelling story about the city’s medieval period and its transition from Muslim to Christian hands. The mosque is located adjacent to one of Toledo’s oldest city gates—Bāb al-Mardūm (Puerta Mayordomo)—which once gave access from the north to the city (today’s neighborhood of San Nicolás). The mosque is one of the few surviving structures from the Islamic period in al-Andalus. Its later conversion to a church, at a time of Christian-Muslim conflict, illustrates how Toledo’s visual culture transcended the religious differences of its Jewish, Christian, and Muslim residents.

Toledo: brief background

Muslims invaded the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal today) in 711 C.E., and ruled Toledo until its takeover in 1085 C.E. by the Christian army of the king of Castile, Alfonso VI. Prior to the Muslim conquest of the city, Toledo had been the capital of the Visigothic kingdom since the fifth century; before that it was under Roman rule. The Muslim conquest of the city was part of an unprecedented expansion of the Umayyad caliphate, centered in Damascus (Syria), which in 711 C.E. reached the land of Sindh (southeastern Pakistan today) in the East, and North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula in the West. After the Umayyads were overthrown by the Abbasids in 750 C.E., a survivor of the Umayyad dynasty—’Abd al Rahman I—escaped and reached the Iberian Peninsula. There, he established at Córdoba a Muslim state (emirate), later declared a caliphate in 929 C.E. The Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm was built in the last years of the Umayyad caliphate in al-Andalus (which fell in 1031 C.E.), when Toledo was the center of its northern dominions.

![[Image 2. Inscription (details?), southwest façade, Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm]](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Mosque_of_Bab_Mardum_Cristo_de_la_Luz_AH_390_1006_Toledo_29417520341-870x411.jpg)

Inscription, Southwest façade, Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, 999/1000 C.E. (photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0)

Inscription, patron, and builder

Importantly, the mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm was one of many private institutions erected by elite, wealthy Muslims (unlike large congregational (or Friday) mosques that were commissioned by the state). It probably functioned as a small oratory that also promoted learning, and received local and visiting scholars and students. In the Islamic world, a mosque functioned both as a place for worship as well as learning; scholars often sat in a designated space in the mosque, where students could find them.

Before entering this small mosque, a visitor would have seen a Kufic inscription on the upper frieze of its southwest façade. The inscription informs the viewer about the mosque’s patron, builder, and year of completion before they even enter the space:

In the name of God the Compassionate, the Merciful, Aḥmad ibn Ḥadīdī caused this mosque to be built, with his own funds, hoping through this to receive eternal compensation from God. It was completed with the aid of God, under the direction of the architect Musa ibn ‘Alī, and of Sa‘āda, concluding in [the month of] Muharram of the year three hundred and ninety [999/1000].

As the Andalusī historians Ibn Bassām (d. 1147) and Ibn al-Khaṭīb (d. 1347) report, the patron, Ibn Ḥadīdī belonged to one of Toledo’s most influential families; they served as judges and ministers under Toledo’s rulers (the Dh’ul-Nūnids).

Interior with four columns with capitals that are spolia, Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, 999/1000 C.E. (photo: peuplier, CC BY 2.0)

Plan, spatial arrangement, and façades

Cut out of the domes of the maqsura of the Great Mosque of Córdoba (created by D. Antonio Almagro Gorbea)

Despite its small size, the mosque introduces a tight geometric plan and a novel spatial arrangement. The use of bricks to sculpt the façade through creating multiple brick planes, as if it is made of layers, is also a novelty. Once inside the space, it almost seems as if the architect converted the maqsura of the Great Mosque in Córdoba into a freestanding mosque.

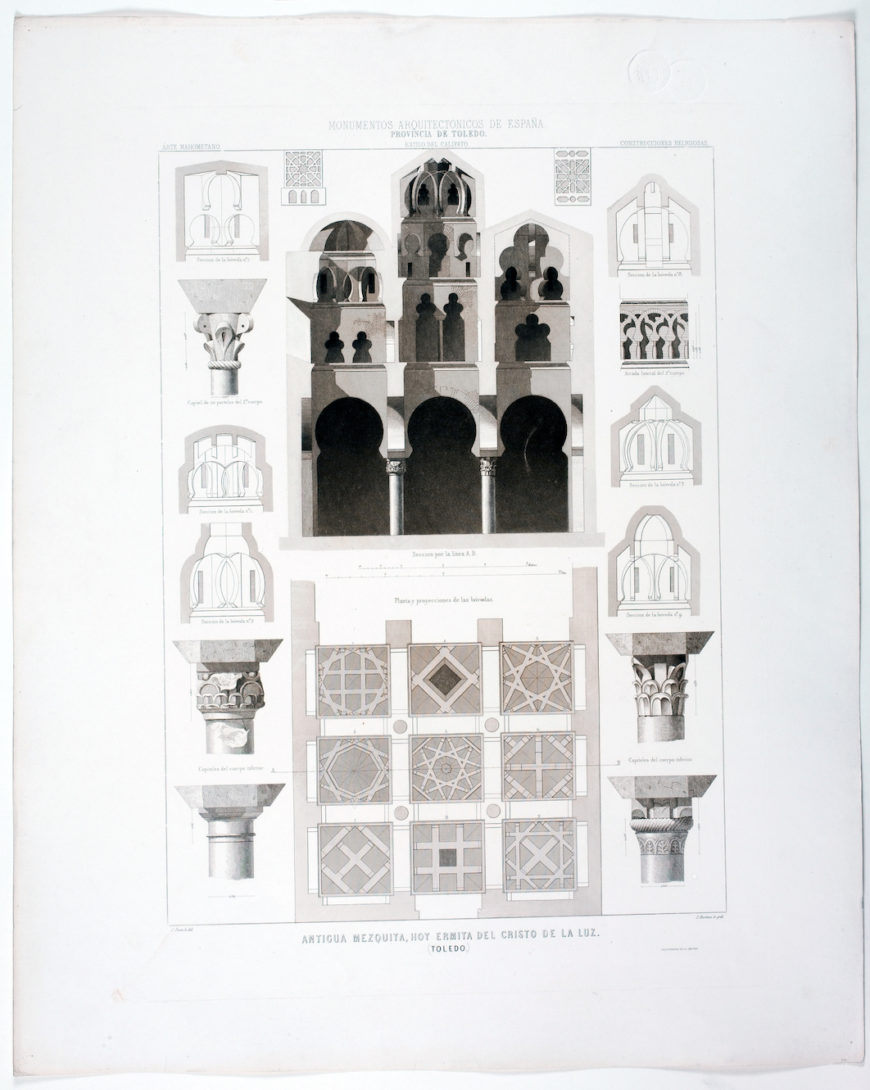

Plan (showing the nine domes on the bottom), section, and column details of the of Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, c. 1858. Drawing by Domingo Martinez Aparici in Monumentos Arquitectónicos de España. Madrid: Imprenta y Calcografía Nacional, 1856–1881 (Museo Nacional del Prado)

The mosque comprises a stone foundation of rubblework that forms a base to its brick walls. Square in plan (8 x 8 meters), it consists of nine equal square bays, demarcated by four central marble columns. The columns and their capitals are spolia, taken from a now-destroyed Toledan Visigothic church. The horseshoe arcades render this small oratory a miniature hypostyle hall.

Horseshoe-arched colonnade, San Miguel de Escalada, 10th century, Spain (photo: David Perez, CC BY 3.0)

This is certainly not the first incident where Muslims reappropriated spolia—in fact, we could look at the the 110 Visigothic and Roman marble columns used in the first phase of the Great Mosque of Córdoba or the Roman tombstones inserted at the base of the minaret of Seville’s Great Mosque (now the Giralda of Seville Cathedral). Building with spolia speeded construction. Such incorporation, profusely practiced worldwide, may have symbolized acceptance of past authority and established continuity with the local heritage by preserving spolia’s sacredness and charged history in the new architectural settings.

Left: One of the domes, interior, Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, 999/1000 C.E. (photo: Manuel de Corselas, CC BY-SA 3.0); right: left dome, maqsura, Great Mosque of Cordoba (photo: Manuel de Corselas, CC BY-SA 3.0)

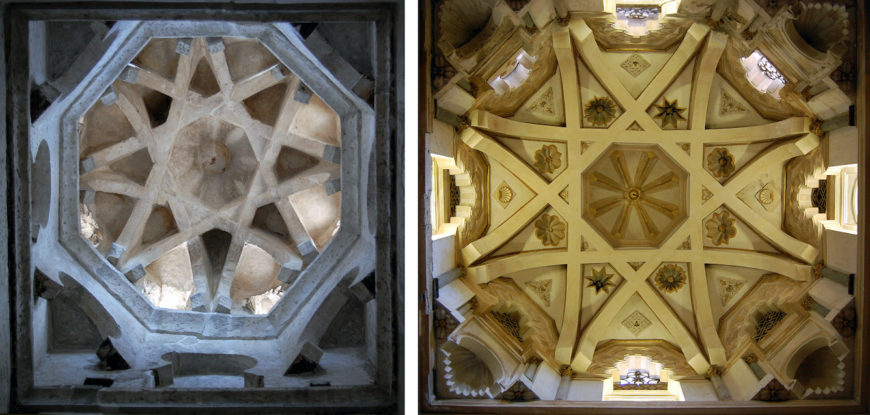

Adding to the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm’s richness, each of the nine square bays is surmounted by a soaring ribbed dome of a different vaulting design, evoking those covering the maqsura of the Great Mosque of Córdoba. Just as in the maqsura of Córdoba’s Great Mosque, where this type of vaulting first appeared on the peninsula almost fifty years earlier (960s C.E.), each square bay carries a multi-tiered set of lobed arches that rises high, and is surmounted by a dome of interlacing ribs. While only three such domes cover the maqsura, those of Bāb al-Mardūm replicate these three, and introduce six novel designs that nearly exhaust the whole potential of such vaulting. The most common design creates, through squinches, an octagonal base over the square bay. From this octagonal base, two sets of ribs rise either from the middle or the corner of the octagon, and extend to another, opposite side of the octagon. From this spatial interlacing of the ribs, a central, smaller geometric polygon is created, and is usually carved in the shape of a scalloped miniature dome. Showing remains of paint, the mosque’s domes may have once been polychromatic (many colored).

Southwest façade, Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, 999/1000 C.E. (photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0)

The mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm once stood as a pavilion-like structure open on three sides (now closed in), except for the mihrab on the southeast wall, where the mihrab niche facing Mecca used to be. The exterior facades are enlivened by the use of bricks in different thicknesses to subtly create recessed and projecting planes. The main southwest façade, overlooking the street has three different arched entryways: horseshoe (right), semicircular (center), and lobed (left). On top of these doors, a series of blind horseshoe arches project and interlace in a similar fashion to the interior screens marking the mihrab aisle and the maqsura of the Great Mosque of Córdoba.

Detail of the sawtooth-frame, brick net, and corbels, southwest façade, Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, 999/1000 C.E. (photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0)

Above these blind arches, brick units laid in an angle create a sawtooth-pattern frame that inscribes a diamond-like perforated brick net. This frieze is surmounted by the dedicatory inscription (above), whose angular letters are also created by laying the bricks in both horizontal and vertical alignments. Even the series of corbels that hold the roof, on top of the inscription, are produced by stacking and recessing the bricks.

Diagram showing the transept and apse which were added later (after 1186) after conversion to a church, and the features of the northwest façade of the mosque. Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, 999/1000 C.E.

As one moves around the mosque, the northwest façade features, on its lower level, three recessed horseshoe arched entryways, each framed by a rounded semicircular arch.

Left: horseshoe window with alternating voussoirs framed by trilobed windows, northwest façade, Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, 999/1000 C.E. (photo: Ecelan, CC BY-SA 3.0); right: double arcades with alternating voussoirs, hypostyle hall, Great Mosque at Córdoba, Spain, begun 786 and enlarged during the 9th and 10th centuries (photo: Michal Osmenda, CC BY 2.0)

The upper level consists of six horseshoe windows of alternating voussoirs of red brick and greyish stone, framed by projecting trilobed arches. This use recalls, albeit on a smaller scale, the alternating brick and stone voussoirs of the interior double arcades of the Great Mosque of Córdoba. The mosque is a powerful demonstration of decorative brickwork. Its architectural reference to the visual expressions of the Great Mosque of Córdoba certainly reflected Ibn Ḥadīdī’s prominence and his elevated status.

Conversion into the Church of Santa Cruz

When Alfonso VI seized Toledo from the Muslims in 1085, and made it the capital of the kingdom of Castile, Toledo’s congregational mosque was almost immediately converted into a church (later destroyed to become a cathedral). While the congregational mosque stood at the center of the city, around which the city’s markets and institutions were formed, the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, was on the city’s edge.

For almost a hundred years after the conquest, the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm continued to serve the now much smaller Muslim community. Shifting the Muslim place of worship from the city’s center to its periphery minimized Muslim visibility in the city, as the congregational mosque had constituted the place for Muslims’ social gathering and the starting point of processions (such as funerals) to the different parts of the city.

In 1183, the mosque was given to the Order of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem (also known as Hospitalers), a military religious order, founded in Jerusalem in the 11th century that came to Spain to fight Muslims. In 1186 the mosque was consecrated as a Christian chapel and dedicated to the Holy Cross (Santa Cruz), which was when, as most historians agree, the architectural conversion of the mosque took place.

The conversion from mosque to church was easy due to the architectural adaptability of mosques—in al-Andalus, they were, after all, hypostyle structures (having a roof supported by several rows of pillars) with no images offensive to Christianity (the depiction of animate beings is prohibited in Islamic religious spaces). Conversion often only entailed a change to an East-West orientation and a “cleansing” ritual. Politically and theologically, conversion signaled Christianity as the new religious authority. Moreover, as most mosques either stood on the site of an earlier Visigothic church or were themselves converted churches, their (re)conversion into churches was seen as a legitimate act that returned a monument to its original Christian state. However, ecclesiastical and royal figures also admired mosques (and Islamic palaces) for their artistic refinement.

Interior of the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm after it was transformed. The raised, semi-circular apse in the background was added after 1187. The original mosque dates to 999/1000 C.E., Toledo, Spain (photo: José Luis Filpo Cabana, CC BY 3.0)

The conversion of Bāb al-Mardūm to a church entailed changing the mosque’s orientation by introducing a shallow transept and semicircular apse, which was needed for the altar. Finally, fresco paintings were added to the interior.

Exterior of the apse, Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, with late 12th century additions (photo: Jesusccastillo, CC BY 4.0)

Although the new addition has fewer openings, featuring mainly blind arcades, it could be considered a variation on the corresponding architectural elements of the earlier mosque. It seemingly continues the same brick construction technique to texture the façades. On its lower part, a semicircular blind arcade of recessed planes wraps around the apse area, while on the upper level, a multi-lobed pointed blind arcade frames a recessed keel-shaped arcade. The transept (crossing) portion, situated between the earlier mosque and the new apse, slightly projects almost at wall’s width, signaling a rupture between the old and new, so as to remind the viewer of the existence of two phases: before and after the conquest.

Christ Pantokrator in the apse of Interior of the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm after it was transformed. The apse in the background was added after 1187. The original mosque dates to 999/1000 C.E. The painted red-and-black inscription surrounding the apse area reads al-yumn wa-l-iqbāl, although it is fragmentary in sections today (photo: José Luis Filpo Cabana, CC BY 4.0)

Tiraz of woven linen and silk with Arabic inscription of al-yumn wa-l-iqbāl, 12th century, Fatimid, from a tomb at al-Azam near Asyut (Upper Egypt), 52 x 40 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum)

On the interior of the apse’s semicircular dome, the Christ as Pantokrator (Christ in Majesty) is depicted on a background of blue skies and stars, surrounded by the symbols of the four Evangelists, of which only Mark and John survive. The apse’s lower horseshoe niches once held images depicting saints. The arch leading to the apse area is decorated on the outside with a painted cursive (naskh) Arabic inscription in red and black, featuring the phrase, “al-yumn wa-l-iqbāl” (prosperity and good fortune). This phrase commonly appeared in contemporary Islamic architecture and circulated on luxury portable objects produced in Spain, and on tenth-century textiles made in Fatimid Egypt.

The image of Christ Pantokrator, one of the most best-known depictions of Christ, showcases the power of Christianity and the Church. This message of power—and the triumph of Christianity over Islam—is further conveyed by the Latin inscription on the lower register of the apse from Matthew 25:34: “Then the king will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father. Inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.’”

Given the military nature of the Order of Saint John, and its activity in the crusade against Muslims, one would expect the mosque to have been destroyed. Preserving the mosque may have symbolized triumph and served as a visual manifestation of a trophy or spoil of war. Yet, analyzing the architectural conversion solely from such a triumphalist standpoint overlooks other aspects specific to Toledo’s history and building tradition.

A note on the term Mudéjar

The converted building has often been labeled “mudéjar,” a scholarly term denoting the incorporation of the same architectural elements that were used in the original mosque and in other Andalusī buildings. The so-called mudéjar elements that the mosque displays are its construction in brick, the rigorous use of horseshoe and lobed arches, and its Arabic inscriptions. In other locales, “mudéjar” elements included geometric and vegetal decorative motifs (often executed in stucco), geometric glazed tiles or wooden ceilings, interlacing arches, or ribbed domes.

The term mudéjar is problematic though because, among other things, its original meaning signified Muslims living under Christian rule. The word mudéjar comes from mudajjan, which in Arabic could mean “one permitted to stay” / “one left behind,” or “subjugated”/ “domesticated”/ “tamed.” The term’s use in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to describe certain aspects of art and architecture suggested that adopting the architectural and artistic elements of the foe (the Muslims) by Christian patrons or in Christian-ruled territories paralleled the Christian reacquisition of the land from Muslims. It also associated the art and architecture produced in Toledo, and in al-Andalus more generally, with the predominant religion of Islam, and implied that the building workforce in the lands newly conquered by Christians was and continued to be Muslim (mudéjar). However, in a city like Toledo, where Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived together for almost five centuries before the Christian reconquest, it is difficult to attribute an architectural style only to Muslims. Rather, it is more reasonable to think that it expressed the identity of all city inhabitants. Consequently, we should not assume that those who executed the new additions to the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm were Muslims, as the builders also may have been Christians or Jews.

It is true that the mural program and the new orientation of the church came to assert the Christian faith, especially when figurative art was prohibited in a mosque, but the display of the Arabic inscriptions may allude to a shared culture, language, and taste. After all, Arabic was spoken by members of the city’s three religious groups and was, certainly at this time, not perceived as foreign. Numerous surviving architectural works and objects from the medieval period include multiple languages and testify that Arabic was not the ‘property’ of Muslims. Take for example the Hebrew and Arabic woven into the walls of Toledo’s mid-fourteenth century Synagogue of Samuel Halevi Abulafia; the bi-lingual Christian tombstones from twelfth- and thirteenth-century Toledo; or the Latin, Castilian, Arabic, and Hebrew marble epitaphs of King Fernando III’s tomb (c.1252) in Seville Cathedral. Of course, the interpretation of the use of Arabic varies based on the specific context.

The Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm—and its conversion into the Church of Santa Cruz—is an example that embodies the multi-religious reality of medieval Spain, where architecture and art were informed by the cultural complexity of such a dynamic setting.

Additional resources:

Jerrilynn D. Dodds, María Rosa Menocal, and Abigail Krasner Balbale, The Arts of Intimacy: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Making of Castilian Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 113–122.

Susana Calvo Capilla, “La Mezquita de Bāb al-Mardūm y el proceso de consagración de pequeñas mezquitas en Toledo (s. XI-XIII),” Al-Qantara 20, no. 2 (1999), pp. 299-330.

David Raizman, “The church of Santa Cruz and the beginnings of Mudejar architecture in Toledo,” Gesta / International Center of Medieval Art 38 (1999), pp. 128–141.

Miguel Dolan Gómez, “The Crusades and Church Art in the Era of Las Navas de Tolosa,”Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia 20 (2011), pp. 237–260.

Julie A. Harris, “Mosque to Church Conversions in the Spanish Reconquest,” Medieval Encounters 3 (1997), pp. 158–72.

Ibn Bassām al-Shantarīnī, al-Dhakhīra fī maḥāsin ahl al-Jazīra, vol. 1, section 4, ed. ‘Abd al-Wahab Azzam (Cairo: Maṭba‘at lajnat al-ta’līf wa’l-tarjama wa’l-nashr, 1945).

Lisān al-Din Ibn al-Khaṭīb, A‘māl al-a‘lām, vol. 2, ed. Sayyid Hassan (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, 2003), pp. 176–9.