During ancient Egypt’s last dynasty, a massive cultural exchange occurred between Greeks and Egyptians.

A conversation with Dr. Sara E. Cole, Antiquities Department, Getty Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker, Executive Director, Smarthistory, in front of Mummy of Herakleides, 120–140 C.E., Romano-Egyptian. Human and bird remains; linen, pigment, beeswax, gold, and wood, 175.3 x 44 x 33 cm. Getty Villa, Los Angeles.

During ancient Egypt’s last dynasty, a massive cultural exchange occurred between Greeks and Egyptians, then reflected in art and cultural practices. Learn how this Greco-Egyptian legacy influenced portrayals of the dead, such as for Herakleides.

Getty has joined forces with Smarthistory to bring you an in-depth look at select works within our collection, whether you’re looking to learn more at home or want to make art more accessible in your classroom. This six-part video series illuminates art history concepts through fun, unscripted conversations between art historians, curators, archaeologists, and artists, committed to a fresh take on the history of visual arts.

Egyptian mummy portraits

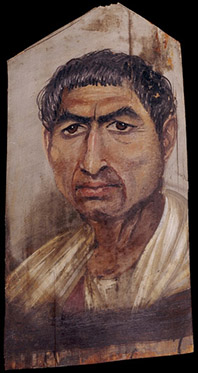

Mummy portrait of a man, c. 100-120 C.E., 40.1 x 21.5 cm, Hawara, Egypt © Trustees of the British Museum

A portrait shows what an individual would have looked like. Ancient Egyptians did not make much use of portraits; inscriptions containing the name and titles of an individual were used for identification purposes instead. Portraits were, however, important in Roman art. They were placed in tombs as a memorial of family members.

This type of portrait appeared in Egypt in the first century C.E., and remained popular for around 200 years. Egyptian mummy portraits were placed on the outside of the cartonnage coffin over the head of the individual or were carefully wrapped into the mummy bandages. They were painted on a wooden board at a roughly lifelike scale. It is possible to date some mummies on the basis of the hairstyles, jewelry and clothes worn in the portrait, and to identify members of a family by their physical similarities.

Mummy portrait of a man

Most mummy portraits that have survived have unfortunately become separated from the mummies to which they were attached. Because of this we rarely know the identities of the subjects.

The subject of this portrait, painted in encaustic on limewood, appears to be a man in his fifties or sixties of strikingly Roman appearance. He is dressed in a tunic with a violet stripe, or clavus, and a thick folded mantle. The hair is brushed forward and cropped in the style of court portraits of the Trajanic period (98-117 C.E.). Pink has been used to highlight his nose and lips, and dark brown to indicate shading and the contours of the face. The portrait gives the impression of age, authority and austerity. These characteristics were very important in Rome, and are here represented in a very Roman manner.

The accuracy of these portraits has often been questioned. Techniques employed by doctors to plan delicate facial surgery have been used to compare the actual appearance of several mummies with their portraits. These techniques have helped prove that the portrait did indeed show the person as they appeared during life. Of course, there was still some element of artistic license; for example, the mummy of Artimedorus appeared to be much more heavily built than he seemed in his portrait.

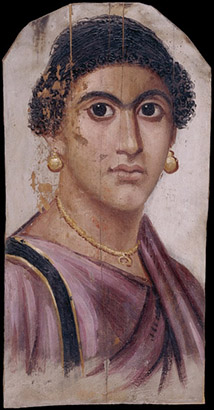

Mummy portrait of a woman, c. 55-70 C.E., 41.6 x 21.5 cm, Hawara, Egypt © Trustees of the British Museum

Mummy portrait of a woman

This portrait is painted in encaustic on limewood. The woman is dressed in a mauve tunic, and a mantle of a darker shade. She wears gold ball earrings and a gold necklace with a pendant crescent and circular terminals. The hair is plaited into a bun at the back of the crown, with snail curls around the brow and at the sides of the head. Her hairstyle, costume and jewelry indicate that she died some time during the reign of the Roman emperor Nero (54-68 C.E.). It has been said that the athletic quality of this portrait is more appropriate to that of a man.

© Trustees of the British Museum