Born in battle, the New Kingdom was initiated by the Theban king Ahmose who brought the Egyptian armies north against the Hyksos kings at Avaris and drove them out of the Nile delta.

The early Eighteenth Dynasty (the first dynasty of the New Kingdom) was characterized by military campaigns that continually pushed the borders of Egypt into Asia Minor and Nubia. Later kings of this dynasty relied more heavily on diplomatic relationships, achieving a position of power and cultural dynamism in the Mediterranean world due to their successes in foreign policy.

Western jamb of the south portal at the palace of Merenptah at Memphis showing the king in the iconic ‘smiting’ pose, controlling enemies of Egypt. Dynasty 19 (Penn E-13575-C)

After the Eighteenth Dynasty experienced a unique and disruptive era of significant religious and political alteration (known as the Amarna Period), the early Nineteenth Dynasty kings reasserted traditional social and cultural beliefs. These rulers emphasized their strategic and physical prowess on the battlefield. Scenes of successful battles, showing the king at the head of his armies triumphing over the chaotic enemy, appear prominently on temple walls as proof of the ruler’s abilities. Later in the New Kingdom, repeated incursions from outside forces (such as the Libyans and the migratory Sea Peoples), weakened the country, eventually leading to a fracturing of centralized control and the Third Intermediate Period.

View of sphinxes, the first pylon, and the central east-west aisle of Temple of Amon-Ra, Karnak in Luxor, Egypt (photo: Mark Fox, CC: BY-NC 2.0)

New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 B.C.E.)

Spanning more than 500 years and encompassing Dynasties 18–20, the New Kingdom is often considered to be the peak of ancient Egyptian culture. The early Eighteenth Dynasty rulers were warrior kings who carried out numerous military campaigns to expand their borders and areas of control, both to the north and the south. These incursions were primarily intended to create a buffer around the Egyptian homeland, exploit valuable resources, and gain control of trade routes.

Eager to reestablish a centralized authority after the chaos of the Second Intermediate Period, the royal court moved back to Memphis, the ancient seat of power from the golden age of the great pyramids. Thebes, however, remained the religious capital. The local god Amun was merged with the sun god Ra and became Amun-Ra—King of the Gods. Amun’s shrine at Karnak developed into the largest temple complex in the country.

A new royal burial site, now known as the Valley of the Kings, was initiated in the hills on the west side of the Nile from Thebes; the first royal tomb cut into the cliffs was for Thutmosis I. Kings dug deep subterranean tombs into the limestone Valley and paired those hidden tombs with grand memorial temples, constructed closer to the Nile edge of cultivation, that served to maintain the king’s cult after death.

One of the most stunning structures from the ancient world is one of these memorial temples, which stands against the dramatic cliffs at Deir el Bahri just opposite the Valley of the Kings. This terraced temple was built by Hatshepsut, the powerful female ruler who controlled Egypt for roughly 20 years at the height of the Eighteenth Dynasty. She built her memorial monument directly adjacent to the memorial temple of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II, founder of the Middle Kingdom, clearly identifying her righteous rule as a continuation of those who came before.

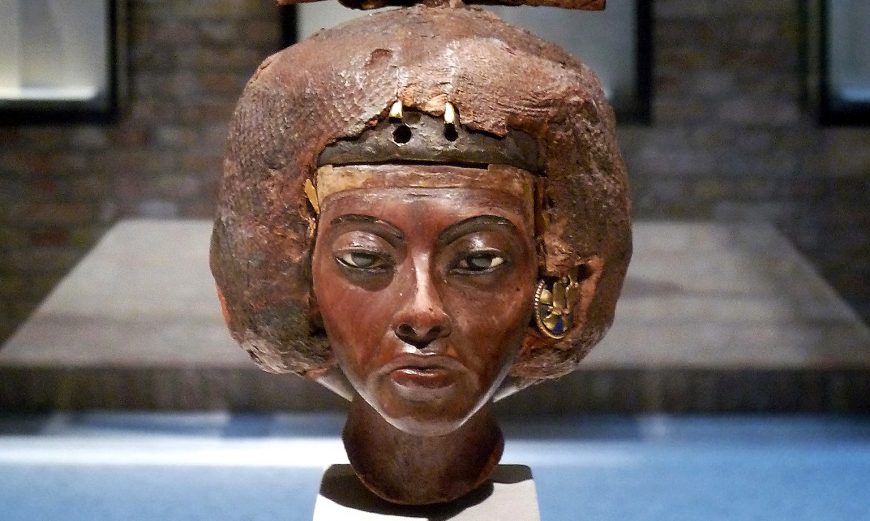

Portrait Head of Queen Tiye with a Crown of Two Feathers, c. 1355 B.C.E., Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, New Kingdom, Egypt, yew wood, lapis lazuli, silver, gold, faience, 22.5 cm high (Neues Museum, Berlin)

After ongoing military campaigns under Thutmosis III led to Egypt’s furthest borders, later kings sought more diplomatic solutions in their relations with other powers in the Near East. These included diplomatic marriages, such as that between Thutmosis IV and the daughter of Mitannian ruler Artatama, and greatly reduced expansionist tendencies. This led to an era of wealth and relative peace under Thutmosis IV’s successor, Amenhotep III. This king focused on developing the religious landscape—enlarging numerous existing chapels and founding several new temples, including the magnificent Luxor Temple. He commissioned an incredible number of divine statues to emphasize his connections to the gods, and authorized some images that gave himself and his chief wife, Tiye, divine attributes.

House Altar depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti and Three of their Daughters, limestone, New Kingdom, Amarna period, 18th dynasty, c.1350 BCE (Ägyptisches Museum/Neues Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

Their son was Amenhotep IV, who changed his name early in his reign to Akhenaten. Akhenaten and his chief wife, Nefertiti, were dedicated to the cult of the Aten, a specific form of the sun god that manifested as a disc. Akhenaten made the radical choice to move the capital to a brand new location at Akhet-Aten (modern Amarna) and centralized control, both secular and religious, in himself as the sole representative of the Aten on earth. In general, this significant break with tradition was not well-received and it did not last.

Akhenaten’s young successor and son Tutankhamun (better known as King Tut), moved the religious capital back to Thebes, re-establishing Amun-Ra as the chief national deity. Akhenaten’s reign was viewed as a time of chaos by later kings; the king list at Seti I’s temple in Abydos jumps from Amenhotep III directly to Horemhab, completely skipping over the contentious reigns of Akhenaten and his immediate successors, Tutankhamun and Ay.

Ramses II ruled for 67 years. Here he is shown slaying an enemy while he tramples on an other in the battle of Kadesh in 1274 B.C.E., inside Abu Simbel, Egypt (photo: Aoineko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Early Nineteenth Dynasty kings resumed military campaigns and re-established Egyptian authority over parts of the Near East. One of the best-known kings from Egypt was Rameses II. He ruled for sixty-seven years, fought great battles with the Hittites, and constructed a huge number of monuments throughout the country. Triumphant battle scenes adorn many of these temples, many depicting the battle of Kadesh despite the fact that he didn’t actually conquer the Hittites—the conflict was instead settled by negotiation and diplomatic agreements.

Later kings of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties faced successive waves of invasions by foreign powers, such as the Libyans and the enigmatic migratory group known as the Sea Peoples. These conflicts were an obvious strain and led to the reduction of the king’s reach and sphere of influence. By the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, the pharaoh ruling from Memphis had little apparent control over a powerful family in Thebes whose members served as high priests at Karnak and who endowed themselves with royal titles.

Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070–713 B.C.E.)

Outer Coffin of the Singer of Amun-Re, Henettawy, c. 1000–945 B.C.E., late Dynasty 21, Third Intermediate Period, wood, gesso, paint, varnish, from Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Tomb of Henettawy F , 203 cm long (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This era was characterized by a distinct split between north and south. During the Twenty-first Dynasty, the kings ruled from the delta while the south was controlled by the high priests of Amun at Thebes. These ruling families were related and often intermarried, helping to maintain a sense of continuity.

Many social and religious customs changed, including the royal mortuary practices. The Twenty-first Dynasty kings at Tanis in the delta initiated a completely new form of royal burial where the burial chamber and chapel were contained within a temple precinct, in the courtyard of the god’s temple, a design that remained in use for royal burials until the Ptolemaic period. Several of these tombs were discovered intact with silver coffins, incredible jewelry, and marvelous vessels. The elaborately decorated private tombs of the New Kingdom became less common. Focus was shifted to remarkable painted coffins, papyri, and wooden stelae that presented most of the required imagery for the ritual provisioning for the afterlife.

Highly skilled metalworking during this time is evidenced in small-scale metal sculptures of divine, royal, and private individuals. These were often exquisitely finished with multiple metals inlaid into the surface in delicate patterns. One of the most beautiful examples is that of Karomama, a queen and Divine Adoratrice of Amun. This elegant statue (53 cm in height) was hollow-cast in bronze and intricately inlaid with gold, silver, and copper to create the elaborate patterns of her costume.

During the Twenty-second Dynasty, a Libyan chieftain who had risen through the ranks became king in the north. He also placed several members of his family in top positions in the Amun priesthood at Karnak in an effort to exercise control over the south. However, later in the dynasty this practice led to a civil war between the regions. Subsequent rulers further complicated royal control when an offshoot of the Libyan royal family founded a rival dynasty that was favored by the Thebans. This period of political instability encouraged local governors to exercise their own authority, further exacerbating the situation.

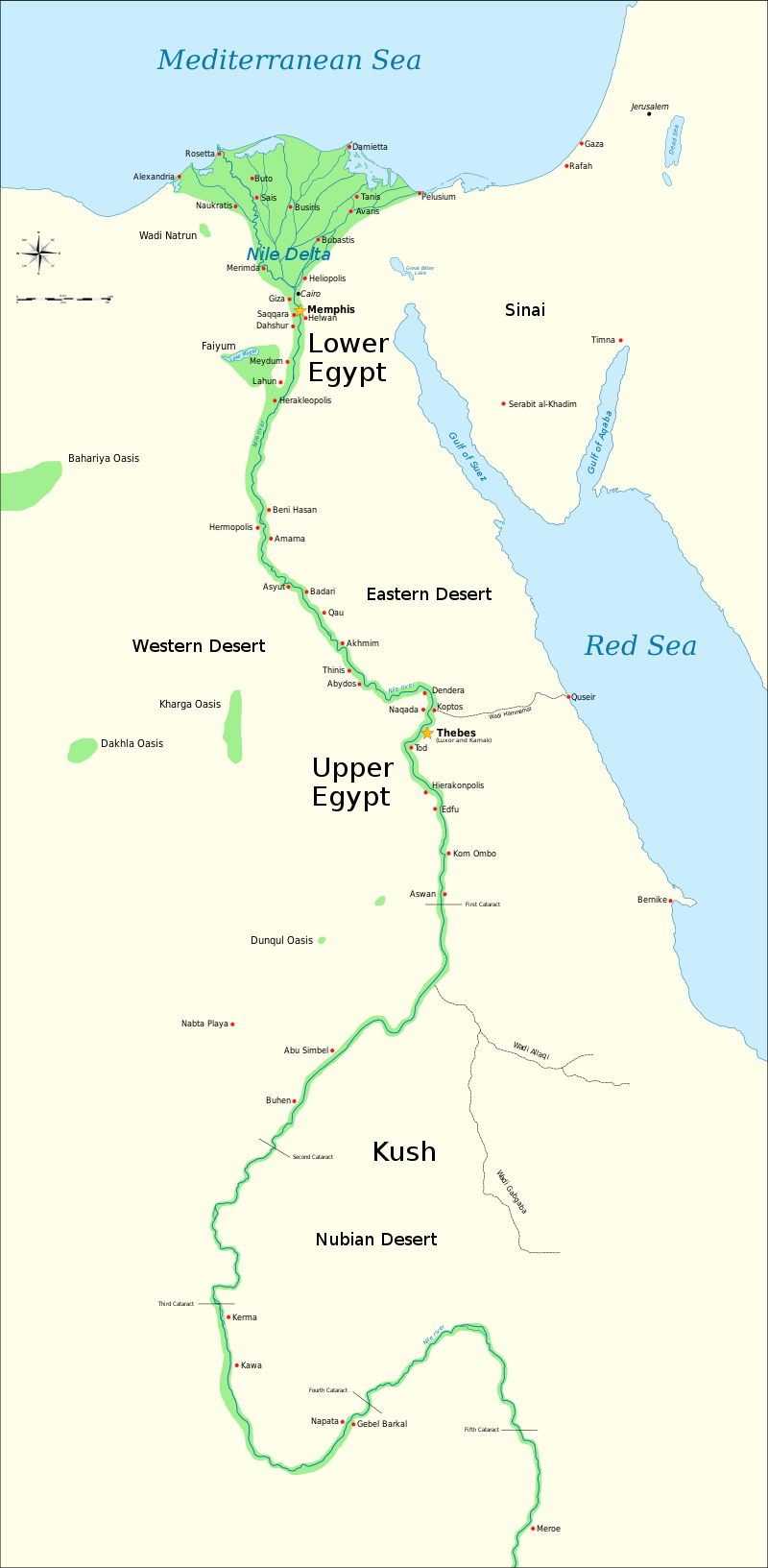

Map of Kush and Ancient Egypt, showing the Nile up to the fifth cataract, and major cities and sites of the ancient Egyptian Dynastic period (c. 3150–30 B.C.) (map: Jeff Dahl, CC Y-SA 4.0)

At this same time, to the south in Nubia, the kingdom of Kush was again on the rise. They pushed their borders north to Thebes, establishing themselves as kings of Egypt and founding the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, bringing the disjointed Third Intermediate Period to a close.

| Period | Dates |

| Predynastic | c. 5000–3000 B.C.E. |

| Early Dynastic | c. 3000–2686 B.C.E. |

| Old Kingdom (the ‘pyramid age’) | c. 2686–2150 B.C.E. |

| First Intermedia Period | c. 2150–2030 B.C.E. |

| Middle Kingdom | c. 2030–1640 B.C.E. |

| Second Intermediate Period

(Northern Delta region ruled by Asiatics) |

c. 1640–1540 B.C.E. |

| New Kingdom | c. 1550–1070 B.C.E. |

| Third Intermediate Period | c. 1070–713 B.C.E. |

| Late Period

(a series of rulers from foreign dynasties, including Nubian, Libyan, and Persian rulers) |

c. 713–332 B.C.E. |

| Ptolemaic Period

(ruled by Greco-Romans) |

c. 332–30 B.C.E. |

| Roman Period | c. 30 B.C.E.–395 C.E. |

Additional resources:

Read an overview of Egyptian chronology and historical framework

Predynastic and Early Dynastic

Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period