Lateran Obelisk, c. 1400 B.C.E., originally erected at the temple of Amun, Karnak by Thutmose III and Thutmose IV at a height of 32 meters; now roughly 4 meters shorter), monolith of red granite, 28 meters high (moved to Alexandria by Constantine, and later erected in the spina of the Circus Maximus in Rome by Constantius II in 357 C.E., re-erected at the Lateran in 1587 by Domenico Fontana for Pope Sixtus V). A conversation with Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker.

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Modern Rome, 1757, oil on canvas, 172.1 x 233 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), see an annotated version with the location of the obelisks in the painting

How do you represent one of the world’s most famous cities? Giovanni Panini’s solution was to create a painting full of paintings. His Modern Rome presents views of this Italian city as it appeared in the 1750s, yet not all of the monuments that he depicts were originally made in Europe.

Painting of the Piazza del Popolo (detail), Giovanni Paolo Panini, Modern Rome, 1757, oil on canvas, 172.1 x 233 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

If you look closely, you will find that six of the views feature tall, pointed pillars in the middle of Rome’s public squares. These monuments are ancient Egyptian obelisks, each made of a solid granite stone narrowing to a pyramidal tip.

In one of his views, an obelisk casts a long shadow across the Piazza del Popolo. Panini emphasizes the pillar’s height as it soars above pedestrians and domed churches. He also captures the contrast between the square’s white buildings and the obelisk’s distinctive reddish stone. In other framed views, similar ancient obelisks appear in the Piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano, Piazza San Pietro, Piazza della Minerva, and Piazza Navona (shown twice).

How did all of these monuments from Egypt end up in Rome? When were they transported and why? Answering these questions takes us into the realm of ancient Mediterranean empires and highlights the long history of looted antiquities and rededicated monuments. We should also ask how often these monuments have been moved around the city of Rome. Their current locations would baffle not only Egypt’s kings, but also Rome’s emperors.

Obelisks dedicated in Egypt

Obelisk of Queen Hatshepsut, New Kingdom, 29 meters tall, 328 tons, the Karnak Temple Complex, Luxor, Egypt (photo: Elias Rovielo, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

By the time Rome annexed Egypt in 30 B.C.E., obelisks had been standing at temples along the Nile River for thousands of years. Egyptians had invented obelisks during the Old Kingdom period (c. 2649–2150 B.C.E.). Rulers typically dedicated these prestigious pillars to sun gods. The monuments’ pyramidal tips, usually encased in reflective metal, referred to the first mound of earth touched by the sun’s rays at the beginning of creation.

In 10 B.C.E., the Roman emperor Augustus began transporting these religious offerings to Italy to adorn his imperial capital. He did so in order to commemorate Rome’s control of Egypt, a place considered ancient even in antiquity.

What sets obelisks apart from other plundered treasures is their immense height and weight: the solid stones could soar several storeys tall and weigh several hundred tons. Transporting them required special boats, and hoisting them upright required extraordinary technical skills. Scholars still debate how ancient engineers accomplished these feats.

An obelisk rededicated in Rome

Augustus is the emperor who seized the obelisk that Panini would later paint in the Piazza del Popolo. Rising 67 feet tall and weighing over 200 tons, the solid pillar initially stood at the temple of Ra-Atum at Heliopolis (near modern Cairo). The pillar’s inscribed hieroglyphs record that the Egyptian king Seti I and his successor Ramses II dedicated the offering. This is one of many obelisks dedicated during the New Kingdom period, when Egypt was at the height of its power and possessed an empire stretching from Libya to Syria.

Obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo (Flaminian Obelisk),, with red granite base added by Augustus, white travertine base added by Sixtus V, and water basins and lions added in the 19th century, Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Hieroglyphs (detail), obelisk in Piazza del Popolo (Flaminian Obelisk), Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Over 1,300 years later, Augustus had the obelisk of Seti I and Ramses II shipped across the Mediterranean Sea and up the Tiber River to Rome. There, he had the monolith set back up, but with a new base made of Egyptian stone. Red granite, quarried at Aswan in southern Egypt, had long been popular for the obelisks dedicated by Egypt’s kings. Augustus’s new base matched the stone of the plundered pillar.

Latin inscription on the base of the obelisk in Piazza del Popolo (Flaminian Obelisk), Rome (photo: Biser Todorov, CC BY 4.0)

Augustus had a Latin dedication carved onto this new pedestal. The inscription recorded that Egypt had been brought under the dominion of the Roman people and that Augustus had rededicated this obelisk to Sol, the Roman sun god. The Latin on the base and the Egyptian on the pillar combined to create a bilingual monument, even if not all viewers were literate and few could read Egyptian.

The emperor installed this monument in the Circus Maximus, ancient Rome’s premier venue for chariot races. The racetrack stood in the city center, about two miles south of the Piazza del Popolo. At the track, the obelisk joined political and religious monuments from different eras to form a central axis, and spectators became used to seeing chariots race around them. [1]

Lamp, Roman, 2nd half of the 1st century, terracotta, 13.2 cm long and 2.9 cm tall (Antikensammlung der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin), view an annotated version

Views of the obelisk that Augustus rededicated here survive in ancient Roman art. On one terracotta oil lamp, we see a contestant driving a four-horse chariot around the Circus Maximus. The monuments on the track’s central axis are behind him: a column monument with a statue on top, the obelisk with hieroglyphs, a lap counter with seven dolphins, another column monument with a statue, an observation platform for judges, and three posts marking the turning point for the next lap. Such images reveal how an obelisk from Egypt became a familiar part of Rome’s cityscape.

Obelisks in the Piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano (left), Piazza Navona (center), and Piazza San Pietro (right), Rome (photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

New Roman settings

By 400 C.E., emperors had set up over a dozen major obelisks in Rome. A few stood in circuses, others were installed at temples and tombs, and one formed part of a solar calendar that you could walk through. [2] Most of these obelisks were transported from Egypt, but some were newly created in the same style. [3]

As Rome suffered natural disasters and invasions in subsequent centuries, obelisks fell, broke into pieces, and became covered by debris. A millennium later, they were rediscovered, repaired, and moved to new public squares being developed by Rome’s Catholic popes, who were eager to showcase the engineering expertise of their own eras. [4] Many ancient obelisks can still be seen in these piazzas, where they are not only far from Egypt, but also removed from the places where Roman emperors had set them up.

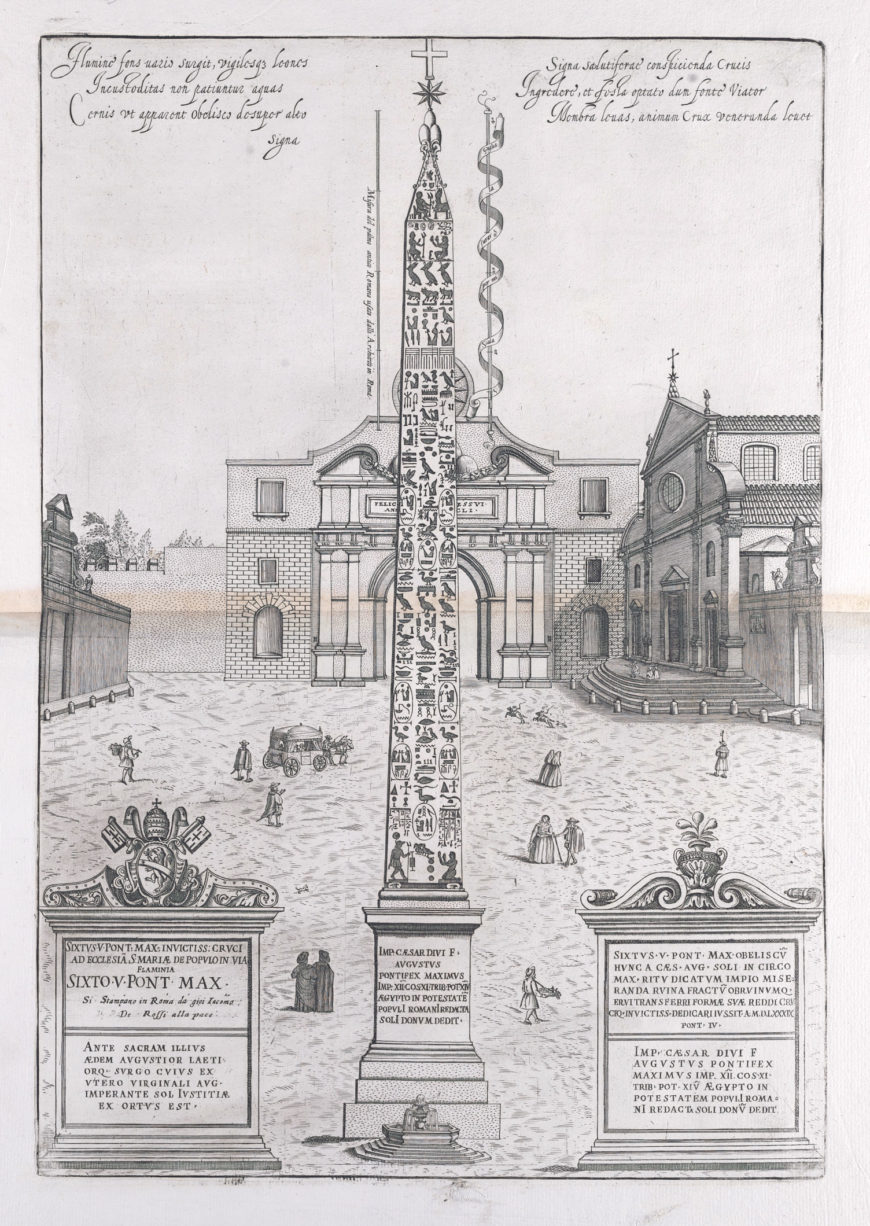

The obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo, seen from the north, with ornate boxes of text describing Pope Sixtus V’s rededication in Obelisks and columns: engravings commemorating the work of Pope Sixtus V produced by G.G. de Rossi after engravings produced by Nicolaus van Aelst in 1589 (Rome: Gio. Jacomo de Rossi, possibly after 1666)

The obelisk that Augustus had rededicated in the Circus Maximus was rediscovered in the 1580s. Pope Sixtus V had it transported two miles north to the Piazza del Popolo, where it was installed near a small fountain. He added yet another base to the obelisk, this one made of white stone taken from an ancient Roman monument (the Septizodium). He also placed a Christian cross at the top, to update the monument’s religious affiliation. The Flemish engraver Nicolaus van Aelst was quick to record this new installation, and the obelisk still appeared this way when Panini painted Modern Rome in the 1750s. By the early 1800s, the Italian architect Giuseppe Valadier had added an elaborate fountain with four lions on stepped pyramids (the Fontana dei Leoni), which can still be seen today. The other obelisks in Panini’s Modern Rome have similar stories of relocation and refashioned bases, some of which were quite extravagant. [5]

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The Piazza del Popolo (Veduta della Piazza del Popolo), c. 1750, etching, 38 x 54 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Obelisks as global monuments

Rome’s emperors, beginning with Augustus, established a precedent for including obelisks in the planning and design of cities outside of Egypt. [6] Rome’s popes built on this precedent by moving the same obelisks to newly defined public squares during the Renaissance and Baroque eras. As a result, residents and tourists became used to seeing obelisks in Rome again. When later artists such as Nicolaus van Aelst, Giovanni Panini, and Giovanni Battista Piranesi recorded these new settings in works that circulated far and wide, viewers abroad became accustomed to seeing obelisks in Rome, too.

Left: Cleopatra’s Needle, Westminster, London (photo: Ethan Doyle White, CC BY-SA 4.0); center: Luxor Obelisk, Place de la Concorde, Paris (photo: Jebulon, CC0); right: Cleopatra’s Needle, New York City (photo: Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Rome is not the only foreign city to possess these ancient skyscrapers. In the 19th century, as Egyptians contended with the British, French, and Ottoman empires, obelisks were once again transported from their homeland and can now be seen in London, Paris, and New York. Architects have also constructed new versions all over the world. The colossal obelisk known as the Washington Monument is so tall that it has an elevator inside and is so prominent that it serves as a symbol of the capital city of the United States.

Robert Mills and Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey, Washington Monument, completed 1884, granite and marble, Washington, D.C.

Ancient obelisks still remain in temple complexes along the Nile River, and the Egyptians of ancient Africa deserve credit for inventing a monument that now adorns so many of the world’s cities. Egypt’s pyramids may be more famous, but obelisks have been just as influential on the history of art and architecture.

Google Street View of the Piazza del Popolo, Rome

Notes:

[1] Following this monument’s installation here, it became common to put obelisks in Roman circuses.

[2] The obelisk now in St. Peter’s Square once stood in the Circus Vaticanus. The obelisk now in the Piazza Navona once stood at the circus of the Villa of Maxentius. The obelisk now in front of the Lateran Palace once stood in the Circus Maximus, as did the obelisk brought by Augustus and now in the Piazza del Popolo. The obelisk now in the Piazza Minerva is thought to have been installed at a temple (perhaps for Isis). The obelisk now installed behind Santa Maria Maggiore and the one now installed on the Quirinal Hill once stood at Augustus’ mausoleum. The obelisk now on the Pincian hill has hieroglyphs naming Antinous and is thought to have been set up at his memorial complex at Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli. The obelisk now in front of the Montecitorio Palace once stood within a solar calendar set up by Augustus. These last four obelisks are not shown in Panini’s Modern Rome, which also omits other obelisks in the city.

[3] The obelisk now in the Piazza Navona, for instance, has hieroglyphic inscriptions naming the Roman emperor Domitian and may date to his reign.

[4] The architect Domenico Fontana (1543–1607) wrote a book about successfully moving the obelisk from the Circus Vaticanus to St. Peter’s Square.

[5] The Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini added an extraordinary fountain beneath the obelisk in the Piazza Navona and sculpted an elephant base for the obelisk in the Piazza Minerva, both visible in Panini’s Modern Rome.

[6] The Byzantine emperor Theodosius built on this precedent by setting up an Egyptian obelisk in the racetrack at Constantinople (Istanbul) around 390 C.E.

Additional resources

Obelisks on the move, from the Getty Iris blog

Jeffrey Collins, “Obelisks as Artifacts in Early Modern Rome: Collecting the Ultimate Antiques,” Ricerche di Storia dell’Arte 72 (2000): pp. 49–69.

Brian Curran, Anthony Grafton, Pamela Long, and Benjamin Weiss, Obelisk: A History (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2009).

Regina Gee, “Cult and Circus ‘in Vaticanum’,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 56/57 (2011): pp. 63–83.

Grant Parker, “Monolithic Appropriation? The Lateran Obelisk Compared,” in Rome, Empire of Plunder: The Dynamics of Cultural Appropriation, edited by Matthew Loar, Carolyn MacDonald, and Dan-el Padilla Peralta (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 137–59.

Grant Parker, “Narrating Monumentality: The Piazza Navona Obelisk,” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 16, no. 2 (2003): pp. 193–215.

Grant Parker, “Obelisks in Exile: Monuments Made to Measure?,” in Nile into Tiber: Egypt in the Roman World, edited by Laurent Bricault, M. J. Versluys, and P. G. P. Meyboom (Leiden: Brill, 2007), pp. 209–22.

Susan [Fern] Sorek, The Emperors’ Needles: Egyptian Obelisks and Rome (Exeter: Bristol Phoenix Press, 2010).

Molly Swetnam-Burland, “Aegyptus Redacta: The Egyptian Obelisk in the Augustan Campus Martius,” The Art Bulletin 92, no. 3 (2010): pp. 135–53.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”lateranob,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:06] We’re standing beside Saint John Lateran, one of the oldest and largest churches in Rome. But we’re here to look at something that is even older, much older. We’re standing in front of an absolutely enormous obelisk from ancient Egypt.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:21] In fact, this is the tallest ancient obelisk known. It took two ships and hundreds of oarsmen to bring it from Egypt to Rome. An obelisk is a monolith. It’s made of a single stone. It’s square at the base and has a small pyramid at the top.

Dr. Zucker: [0:39] Commonly, that would be clad in some kind of metal so that it would be highly reflective. That was appropriate because obelisks were understood by the ancient Egyptians who made them and then by the ancient Romans who imported them as reflective of the divinity of the sun.

Dr. Harris: [0:56] Obelisks are associated with the cult of the sun god by both the ancient Egyptians and by the Romans. They symbolize the rays of the sun and [are] often covered in hieroglyphics and erected often in pairs in front of ancient Egyptian temples.

Dr. Zucker: [1:14] This obelisk is made out of red granite, an incredibly hard stone. The act of quarrying something this size, the act of carving it, of transporting it, of setting it upright was monumental in every respect.

Dr. Harris: [1:28] It’s easy to see why a conquering ruler would want to take these obelisks from Egypt and bring them home with them. This particular one was so enormous, so impressive, that previous conquerors had decided to leave it alone and not offend any gods who might be associated with it.

Dr. Zucker: [1:47] While most obelisks were set up in pairs, ancient chroniclers tell us that this obelisk existed alone in a temple to the sun in the great city of Karnak. It remained there until the fourth century, when Constantine the Great visited Egypt in the year 301 and may have seen this obelisk.

[2:08] Later, he would order its removal. It was taken down and a special boat was built to move it from Karnak to Alexandria, from which it would be transported.

[2:17] But Constantine dies, and it would remain in Alexandria for two decades until his son, who is known as Constantius II, would have, we think, three ships built in order to transport it across the Mediterranean.

[2:31] Two ships straddled the obelisk on either side as it lay between them, and a third ship at its prow to break the waves. It was then brought up the Tiber and transported by sled to the Circus Maximus, a large racetrack right beside the imperial palace. This obelisk was set up in an island in the center around which the chariots would race.

Dr. Harris: [2:53] The Roman Empire had a centuries-old relationship with Egypt. In 30 B.C.E., Egypt became part of the Roman Empire. Augustus and many other Roman emperors were interested in bringing obelisks from Egypt back to Rome.

Dr. Zucker: [3:12] As Rome became Christianized, the ancient city fell into disrepair and the population was drastically reduced. Now, the Circus Maximus is a fairly marshy area and so an obelisk of enormous weight would eventually become destabilized. This obelisk ultimately fell and broke into three pieces.

Dr. Harris: [3:32] It was discovered under layers of mud more than a thousand years later in the late 1500s. A year later, it was re-erected, this time not in the no longer used Circus Maximus, but the very important Christian site of Saint John Lateran.

Dr. Zucker: [3:49] This is extraordinary historical continuity from the original patrons, Thutmose III and Thutmose IV, to the ancient Roman Emperor Constantine and his son who transported the obelisk, to Pope Sixtus V, who had this obelisk repaired and re-erected.

Dr. Harris: [4:07] It’s really important to see the interest in obelisks that develops in the Renaissance as part of this interest in the ancient world, both ancient Rome but also ancient Egypt.

Dr. Zucker: [4:19] The ancient Romans looked at the grandeur of ancient Egypt, of their engineering capabilities, of their extraordinary skill, and their triumph over that culture made ancient Rome even greater. When the obelisk is re-erected by the Pope for the Catholic Church, an inscription is added to the base that tells the extraordinary history of this object.

Dr. Harris: [4:43] Today, as we walk around Saint John Lateran, a church built on land once owned by the emperor Constantine, given to the church to establish a church and a palace here for the popes, we can stand and look at an enormous obelisk covered in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics that takes us back millennia to ancient Egypt through to ancient Rome, the Renaissance, and here into the 21st century.

[5:13] [music]