Pan Tianshou, Red Lotus, 1963, ink and color on paper (hanging scroll), 161.5 x 99 cm (Pan Tianshou Memorial Museum, Hangzhou)

In Pan Tianshou’s Red Lotus, a single brushstroke of black ink portrays the spindly stalk of a lotus flower emerging from pools of murky ink, its one blossom precariously tilted open toward an inscription above. The image appears strikingly modern in the angularity of its forms, the asymmetry of its composition, and its expressive brushwork. The subject of a lotus flower typically conveys a classical image of springtime leisure and beauty in Chinese painting, one that may also function as a trope for the purity of the Buddha. However, Pan pictured the flower not in its typical pale pink, but a deep, crimson red, demonstrating new Chinese Communist Party ideals for art.

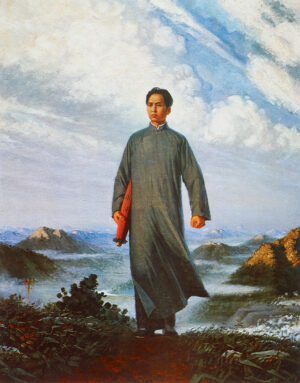

The Cultural Revolution that began in 1966 was a decade-long campaign led by Communist revolutionary Mao Zedong (the leader of the People’s Republic of China or PRC) to advance China’s progress as a modern nation by purging traditional ideas. During this period painters who worked with the longstanding traditional medium of brush and ink in particular harbored concerns for the future of their art and even their lives. Many turned to oil painting in the realistic mode of socialist realism favored by Mao and the Party, such as we see with Liu Chunhua’s Chairman Mao en Route to Anyuan.

With Red Lotus, Pan responded to this sensitive moment on the eve of the Cultural Revolution, by employing guohua 国画, or “national painting” in a transgressive manner. His painting emphasizes the relationship between the ink painting and Chinese identity in the modern era.

Guohua as modern ink painting

Traveling to Japan in the 1920s as a professor of Chinese painting, Pan maintained that the tradition of Chinese painting held the answers to its modern future. Over the following decades, Pan watched as many of his colleagues turned to oil painting or experimented with abstract modes popular in Europe and the United States. Pan remained an ardent teacher of Chinese ink painting, known for his gentle demeanor and skill in teaching the formal principles of brushwork and composition. While Pan also experimented with form and technique, he drew on traditional subject matter and bold, expressive brushwork to transform Chinese painting from a scholarly tradition into a modern, national art form.

Pan Tianshou, Black Chicken on the Rock, 1948, hanging scroll, ink and color on paper (finger painting), 68 x 136.5 cm (Pan Tianshou Memorial Museum, Hangzhou)

Pan had just made a major breakthrough in his work when the Nationalist government of the Republic of China fell to the Chinese Communist Party in 1949. In Black Chicken on the Rock, he arranged a flat, angular portrayal of a chicken perched atop a mossy rock in a large horizontal format rather than the typical vertical format of the hanging scroll. As indicated by the round ink dots that form little pools of ink, Pan often painted not with the brush, but rather with his fingers, which lent a rustic and sketchy flavor to the paintings. Here, the layers of dots, in combination with the large, lightly colored square rock, imbue the composition with rhythm and contrast. The bird seems ominous atop the pale colors of the stone, and the entire painting conveys a sense of immensity through grand scale.

By the 1960s however, the artistic climate that previously fostered bold experimentation and self expression had shifted to align with the Chinese Communist Party imperative to create art for the people in the realistic mode. Red Lotus captures the emotional intensity of Black Chicken while further refining the traditional expressive features that characterize it as an example of guohua (national painting).

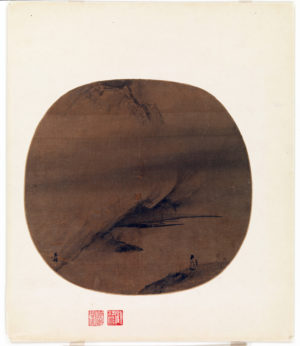

Liang Kai, Poet strolling by a marshy bank, early 13th century, Southern Song dynasty, fan mounted as an album leaf; ink on silk, 22.9 x 24.3 cm, China (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Red Lotus demonstrates classical literary ideals of expression, conveyed by the contrasts of the brushstrokes and tonal gradations of ink. Each stroke may suggest the gestures and even the sentiments of the artist, as well as the textures and nature of the subject itself. Moreover, the calligraphic script along the top of the composition complements the bold angularity of the open lotus flower, weaving together the poetic inscription and the picture. The composition, too, is referred to as a “one-corner composition,” in which the formal elements are arranged into one corner of the composition, leaving room for the addition of a poem or simply to heighten the impact of the image.

Although the stark void and minimal use of imagery seems quite modern, this technique has been well known in Chinese ink painting since the Southern Song dynasty, when court painters like Liang Kai created imagery to evoke the sensual experience of nature, whether landscapes or bird-and-flower paintings—the same genre of Red Lotus. The challenge of ink painting in the 1960s, however, was to adapt classical subjects and techniques such as these to the revolutionary agenda of Mao and his circle.

Lotus and waterbirds (detail), c. 1300 (Yuan dynasty), pair of hanging scrolls, ink and color on silk, 141.6 x 67.9 cm each (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Pan rendered the classical subject of the lotus as a strikingly modern image, emphasizing its red hue in both the painting and inscription. The lotus commonly appears as a light pink blossom in spring, emerging from circular, emerald-green leaves that float on top of ponds. However, Pan indicated in his poetic inscription that the reflection of the flower was “shining red,” words that became a mantra in the coming years when the Communist Party mandated art to be “red, bright, and shining” (hong, guang, liang 红光亮). The poem reads:

Colorful clouds and dewdrops on the jade screen,

The brilliant reflection of the flower, shining red.

Drunken Liulang in his decadence,

Who will support him atop the emerald curtains?

彩云凝水玉屏风,

艳映花光翩翩红。

醉后六郎颓甚矣,

凭谁扶入翠帷中

In his poem, Pan likened the lotus to Zhang Changzong (nicknamed Liulang), who rose to power in the eighth century as a lover of empress Wu Zetian. As the story goes, the decadent Liulang relied on his charming appearance to curry favor. This interplay between text and image is distinctively Chinese, as is the ambiguity of its reference. Is Pan portraying the heavy blossom on its spindly stalk to satirize the drunken officials of bygone days, or is the red lotus a subtle parody of the present? Undoubtedly, Pan’s unusual choice of a red lotus allowed a certain amount of leeway for making literary allusions in a time when the Communist Party generally looked down upon all classical elements as backward-looking and elitist. Nonetheless, Red Lotus demonstrated that while individual artistic expression was at the heart of traditional literati painting, these same principles could be steered toward guohua as a form of expression that represented the new, modern China. In other words, Pan presented a modern approach to Chinese ink painting by cloaking it in Mao-era ideals.

Tragedies of guohua in the Mao Era

When Mao came to power in 1949, Pan and other ink painters grappled with Communist Party aims to make art clear and relevant to the populace. Mao and his circle believed that that art should not require the sophisticated knowledge of urban elites, such as poetic allusions or historical references, which reflected the differences in class and education in China. As for guohua, cultural leaders were divided as to whether or not it could be adapted to revolutionary needs. While established artists like Qi Baishi, Liu Haisu, and Huang Binhong were left to go on painting in their own way, masters of the next generation like Pan were under great pressure to dedicate their art to Mao’s revolution by painting images of reconstruction, dam building, and peasant life, or by illustrating a line from a poem by Mao in a landscape painting.

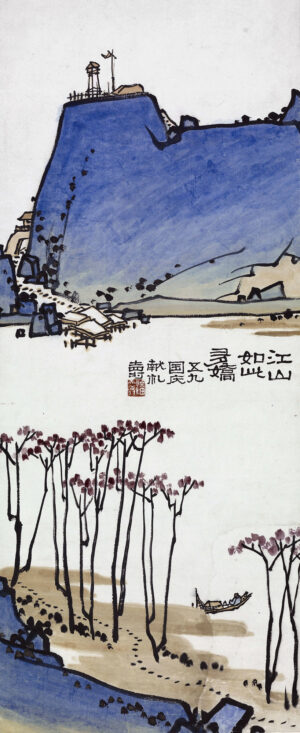

Fu Baoshi and Guan Shanyue, Such is the Beauty of Our Rivers and Mountains, 1959, Great Hall of the People, Beijing (photo: Gisling, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the landscape painting, This Land So Beautiful, Pan illustrated a line from Mao’s poetry while creating a composition defined by bold contour lines, round drops of black ink, and angular forms set against a white, unpainted void. The subject was not unique—in fact, fellow ink painters Fu Baoshi and Guan Shanyue were commissioned to portray the same subject in a grand-scale mural positioned in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. However, like Red Lotus, Pan’s version of This Land So Beautiful demonstrated his commitment to abstract, geometric portrayals rather than the use of realistic landscape elements, sense of perspective, and thoroughly painted composition that Fu and Guan incorporated into their mural.

As a prominent figure in China’s top art academies, as well as a poet and theorist, Pan clearly aimed to bend to Party aims—but his efforts were deemed insufficient. As the Cultural Revolution intensified between the years of 1966 and 1976, Pan suffered persecution, like many others. After years of torture, he died in 1971, despite his tremendous contributions to the national tradition of ink painting.