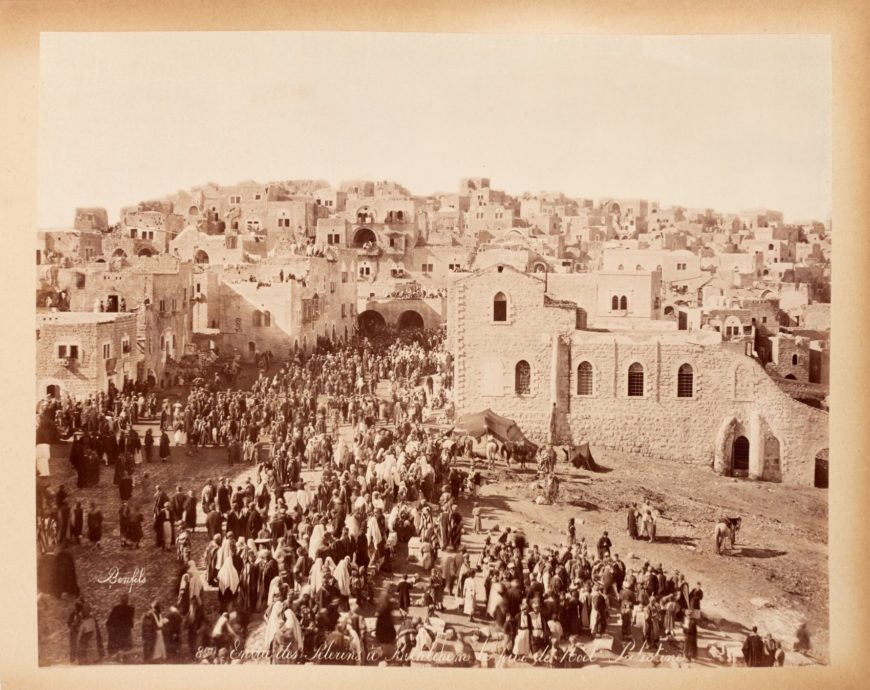

Bonfils Studio, Pilgrims entering Bethlehem on Christmas Day, c. 1870–89, gelatin silver print, 21 x 27.2 cm. Félix Bonfils was a French photographer who opened a studio in Beirut, Lebanon named “Maison Bonfils” that produced views of Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Greece that were sought after by tourists (photo: Sothebys).

Whether for a medieval traveler or a modern tourist, souvenirs can help us remember a journey. Through their materials and imagery they act as a stimulus to help us access the past. They also offer proof of travel to all who see them—communicating complex messages about social identity and even religious beliefs. For pilgrims (those embarking on a journey to a sacred place), souvenirs allowed their owners to reimagine their encounter with the divine from afar. In the medieval period, such objects were also believed to assume the virtues and miraculous powers of the holy site from which they came. As such, they offered a powerful outlet to visualize and access the divine.

Christian souvenirs from the Holy Land

The Holy Land—encompassing the city of Jerusalem and its environs—offered Christian pilgrims the opportunity to visit the sacred sites associated with figures from the Hebrew and Christian Bibles. Pilgrimages to the region began as early as the fourth century, and the production and collection of souvenirs and memorabilia flourished. These objects, ranging from natural to man-made, were considered to have therapeutic and transcendent properties, allowing travelers to retain a material connection to the holy sites when they returned home.

Christian pilgrims hoped to bring home a relic, such as a piece of the True Cross. Following its miraculous discovery in Jerusalem in the 4th century, fragments that are by tradition alleged to be those of the True Cross were displayed in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher for worship on special days. According to one 4th-century pilgrim, Egeria, some pilgrims were even recorded to have illicitly bitten off pieces from the displayed fragments of the True Cross!

Left: Inside cover of a reliquary box; right: interior of the box with stones from the Holy Land, Syria or Palestine, 6th century, 24 x 18.4 x 1 cm (Museo Sacro, Musei Vaticani). The images painted on the inside of the lid are arranged according to a precise ascending order (from left to right and from bottom to top), in order to form a concise “Christmas” cycle (with the Nativity and Baptism in the Jordan), followed by an equally short “Easter” cycle (with the Holy Women at the tomb and the Ascension), divided by the central scene of the Crucifixion.

Pilgrims also collected materials such as soil, rocks, and clay, from a sacred site—materials which assumed sanctity through their proximity to the divine. One 6th-century reliquary contains bits of stone, wood, and cloth labeled with locations from the Holy Land, such as Bethlehem or “from the life-giving [site of] Resurrection.” Together, the collected materials, their identifying labels, and the painted scenes from the life of Christ on the box’s lid work to recall the specific holy sites and their associations with the biblical narrative.

Pilgrim flask with an image of Saint Sergios, 6th–7th century, tin-lead alloy, Rusafah, Syria, 5.4 x 3.81 x 1.59 cm (Walters Art Museum)

Mass produced pilgrim’s flasks, or ampullae, offered an inexpensive alternative to carry home sanctified substances from a saint’s shrine, such as oil from a lamp hung above a saint’s coffin, or water made holy through contact with the saint’s body. Unlike the bones or clothing of a saint, which could not be replaced, holy water and oil were easily replenished, and therefore ideal souvenirs.

Ampullae of holy oil or water could be worn as a pendant around the neck, suspended in the home, or hung over an altar. Pilgrims also often chose to be buried with these flasks, since they identified the deceased as a pious pilgrim and offered protection against evils in the afterlife. The ampulla above depicts St. Sergios on horseback with an inscription that reads “Blessing of the Lord of Saint Sergios.” Sergios was an officer in the Roman army who was martyred in the 3rd century when his Christian faith was discovered.

In 638 C.E., following the Muslim conquest of the Holy Land by the Umayyads, Christian travel within the region became increasingly difficult and was largely displaced by pilgrimage to the Church of Santiago de Compostela (in what is now Spain) and to the tombs of Saints Peter and Paul in Rome. However, the reconquest of Jerusalem and its environs by Christians in 1099 brought a renewed influx of pious Christian pilgrims and crusaders to the Holy Land—and therefore a substantial market for the production of souvenirs.

![[Image: Pilgrimage ampulla from Jerusalem with depictions of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (front) and two warrior saints (reverse)(British Museum)]](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/1613337106-1-copy-870x646.jpg)

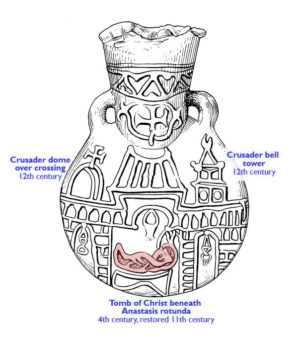

Pilgrimage ampulla from Jerusalem with depictions of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (front) and two warrior saints (reverse), 12–13th century, lead, made in Jerusalem, 56.6 x 37 mm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Line drawing of images on the Pilgrimage ampulla from Jerusalem (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

This 12th-century ampulla depicts (on the front) the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem (which still stands), said to contain the sites of Jesus’s crucifixion, entombment, and resurrection. Under the central arch we see Christ’s body on a tomb. To the left is a domed arch with a cross and to the right, a tower with a pointed roof.

The architecture on the ampulla reflects the appearance of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher as it appeared in the 12th century following a reconstruction campaign undertaken by the crusaders. Along with the existing Anastasis Rotunda (the domed space over Jesus’s believed burial site), the Crusaders built a bell tower and a large dome surmounting the crossing of the new crusader church—changes that are still visible today. By rendering the church in its contemporary, 12th-century form, the ampulla visually collapsed the biblical past with the pilgrim’s present, allowing them to feel as if they were personally experiencing the moment of Christ’s burial and resurrection with each viewing.

Left: Dome of the Rock depicted on a Beaker, Syria or Egypt, c. 1260 (Crusader), glass with gilding and enamel, 18.5 x 12.1 cm (Walters Art Museum); right: Jesus’s Entry into Jerusalem depicted on a Beaker, Syria or Egypt, ca. 1260 (Crusader), glass with gilding and enamel, 17 x 11.1 cm (Walters Art Museum)

Two 13th-century enameled and gilded glass beakers similarly present imagery of the Holy Land, including representations of the Dome of the Rock (originally built by the Umayyads), which the crusaders converted into a church, and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, along with figures of saints and biblical scenes (such as Jesus’s Entry into Jerusalem).

Alongside this recognizable Christian imagery are Arabic inscriptions, such as “Glory to our master, the sultan, the royal, the learned.” The Arabic text, coupled with the use of enameled and gilded glass, common in Ayyubid glassware, tell us that the beakers were produced in Syria or Egypt around 1250. The mixture of Christian scenes and Arabic inscriptions make it difficult to pin down the original function of the glasses or the identities of their owners. They may have served as souvenirs for crusaders or pilgrims. By the mid-13th century, when Muslims once again ruled the city of Jerusalem, the beakers might have allowed their Christian owner, who had perhaps returned with these objects to Western Europe, to feel close to these holy sites, and their relics and liturgies (public worship). Alternatively, they may have served a local Christian clientele—the Arab-Christian population living in the Holy Land who wanted objects decorated with the monuments they patronized and the language they spoke on a daily basis.

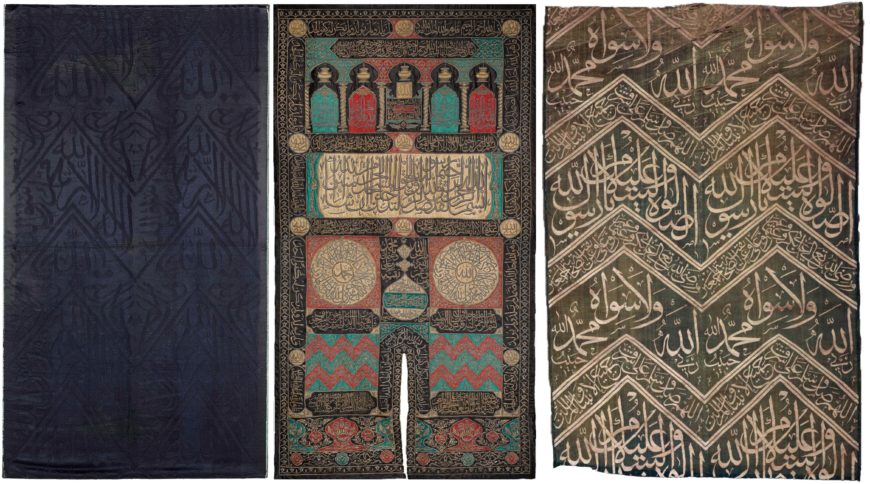

Left: Section from the kiswa of the Kaaba, late 19th or early 20th century, Cairo, or possibly Mecca, silk, 158 x 89 cm (The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art); center: Sitara of the Kaaba, 17th century, silk and silver-gilt wire, 499 x 271 cm (The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art); right: Textile from the tomb of the Prophet in Medina reused as a tomb cover, 18th century, silk, 99.1 x 68.6 cm (Cooper Hewitt Museum)

Commemorating the Hajj

Every year, Muslim pilgrims perform the Hajj, the obligation of the fifth pillar of Islam, by making the journey to the birthplace of Muhammad, the city of Mecca, in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Returning pilgrims brought home a range of memorabilia, including objects that have specific connections to and/or depict the holy sites from their travels. Each year, some of the textiles that adorn and cover the Kaaba (the holiest shrine in Islam) in Mecca, as well as the Prophet’s tomb in Medina, are replaced. The retired fabrics, including the kiswa (the black textile covering of the Kaaba), the sitara (the door curtain), and the red and green zigzag patterned textiles that adorn the interiors of the Kaaba and the Prophet’s tomb, respectively, were cut up and offered to dignitaries or pilgrims to take home as gifts. Members of the Ottoman royal family reused some of the larger pieces as tomb covers, while pilgrims fashioned scraps into garments, headcoverings, and Qur’an cases.

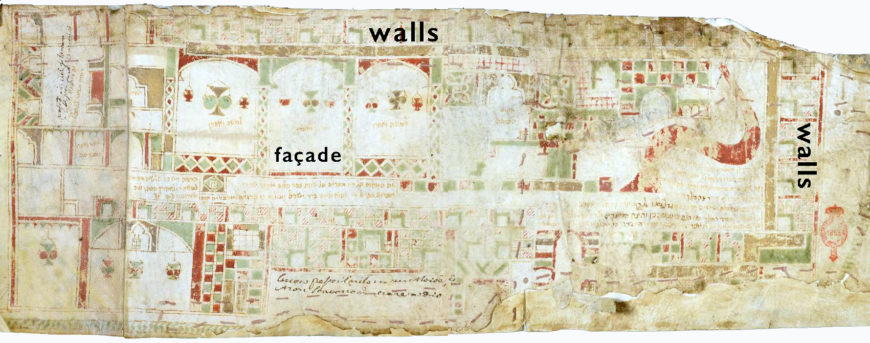

![[Image: Timurid ‘Umra certificate for Sayyid Yusuf bin Sayyid Shihab al-Din Mawara al-Nahri, 1433 C.E., Najaf, Iraq, 665 x 34.7cm, paper, watercolor, ink, gilt paint, The Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, MS.267.1998,]](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/unnamed-1-870x54.jpg)

Timurid ‘Umra certificate for Sayyid Yusuf bin Sayyid Shihab al-Din Mawara al-Nahri, 1433 C.E., Najaf, Iraq, 665 x 34.7cm, paper, watercolor, ink, gilt paint (Museum of Islamic Art, Doha)

Map showing cities with important pilgrimage stops, including Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, Hebron, Najaf, and Karbala (underlying map © Google)

Beginning in the late 11th century, and continuing through the early modern period (c. 1400–1800), artists produced Hajj certificates (quasi-legal documents that certified the completion of the Hajj by an individual or by proxy for another). These certificates, typically in scroll form, combine written text with hand drawn or block print images of major stations of the Hajj landscape, including the Kaaba in Mecca, the Prophet’s Mosque and tomb in Medina, and the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

As a legal document, the scrolls verified the journey of the hajji, or pilgrim, and offered them a personal memento of their spiritual encounter. Some scrolls incorporate ornament and gold decoration, suggesting that they were intended to be hung and displayed in public, where they would have proclaimed the prestige and honor of the pilgrim. They also recorded the spiritual choreography of pilgrimage, creating an access point to commemorate the past journey and transport (by means of memory or imagination) the pilgrim, and any other viewers, to the places represented in the scroll.

The impressive 15th-century pilgrimage scroll (the Timurid ‘Umra certificate above), measuring nearly 22 feet in length, depicts pilgrimage stops in and around Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, Hebron, Najaf, and Karbala. Simplified renderings of the holy structures are interspersed down the length of the scroll with elaborate calligraphic bands. The buildings themselves are rendered from multiple perspectives that make sense as a unified image.

Detail of the The Great Mosque of Mecca with the Kaaba (left) and sandal of Mohammad (right), Timurid ‘Umra certificate for Sayyid Yusuf bin Sayyid Shihab al-Din Mawara al-Nahri, 1433 C.E., Najaf, Iraq, 665 x 34.7cm, paper, watercolor, ink, gilt paint (Museum of Islamic Art, Doha)

An image of the Great Mosque of Mecca shows the Kaaba at its center, dressed in the kiswa and punctuated with a golden band, the hizam, or the embroidered belt containing the shahada, the Muslim confession of faith.

The scroll also includes a stylized image of the Prophet Muhammad’s sandal, considered holy since it was close to the throne of God during Muhammad’s ascension. Inscriptions mentioning its talismanic use, and in particular its therapeutic powers, enclose the sandal. We can imagine this scroll acting as a guide or visual reminder of the holy places of Islam as well as as a powerful amulet, offering the pilgrim protection, blessing, and cleansing from sins.

Talismanic pilgrimage scroll signed by Sayyad Muhammad Hasan Cishti, Indian, probably Deccan, 1787–88, 918 x 45.5cm, watercolor, black and red ink, and gold on paper, (Aga Khan Museum)

An 18th-century pilgrimage scroll produced in the Deccan region of India similarly includes motifs and texts believed to have magical properties. The first half of the scroll follows the standard format of Hajj certificates, incorporating representations of significant sites of the Hajj, including the Great Mosque of Mecca and the Kaaba, among others.

Left: detail of the Great Mosque of Mecca and the Kaaba; right: talismanic motifs, including a human calligram. Talismanic pilgrimage scroll signed by Sayyad Muhammad Hasan Cishti, Indian, probably Deccan, 1787–88, 918 x 45.5cm, watercolor, black and red ink, and gold on paper (Aga Khan Museum)

The latter half features several talismanic symbols, including a calligram (an image formed out of words). The names of the Prophet Muhammad and his son-in-law and companion ‘Ali, executed in mirror-script, form a human head. Beneath, the word Allah creates the neck, and the name Muhammad stretches to depict the rest of the figure’s body.

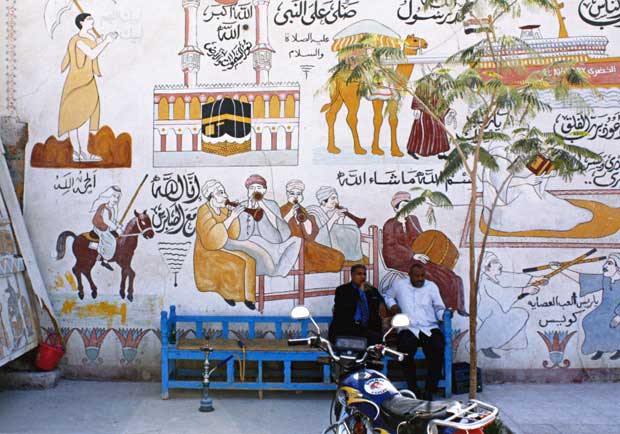

Courtyard of a house, photograph by Khaled Hafez, 2009. The mural depicts part of the Hajj pilgrimage with verses from the Qur’an (Courtesy of British Museum, London)

Like pilgrimage scrolls, the modern tradition of Hajj murals, practiced among Muslims living south and east of the Mediterranean, especially in Egypt, similarly commemorates the pilgrims’ journey and advertises to their family, friends, and neighbors their prestige and baraka (divine blessing) received through their successful pilgrimage. Hajj murals with motifs of holy places as well as images of the pilgrim wearing ritual garments are painted on the exterior walls of a pilgrims’ house when they accomplish the pilgrimage to Mecca.

Jewish pilgrimage certificates

When the ancient Jewish Temple still stood in Jerusalem (957–587 B.C.E. and 516 B.C.E.–70 C.E.), Jews traveled to the city three times a year to participate in annual pilgrimage festivals. Even after the Romans destroyed the Temple in 70 C.E., and such celebratory ritual pilgrimage to the Temple was no longer possible, Jews continued to make pilgrimage to the holy city to mourn the lost Temple as well as to worship at other sacred sites, such as the tombs of the biblical patriarchs or prophets.

Depictions of Holy Places and Temple Vessels, two vellum fragments of a Sephardic manuscript, Garret Hebrew MS 4, 15th or 16th century, 1. 17 inches long, 5 inches high. 2. 16.5 inches long, 5 inches high (Princeton University Library)

Detail of Cave of the Patriarchs with crescent symbol, Depictions of Holy Places and Temple Vessels, one of two vellum fragments of a Sephardic manuscript, Garret Hebrew MS 4, 15th or 16th century, 1. 17 inches long, 5 inches high. 2. 16.5 inches long, 5 inches high (Princeton University Library)

Although no substantial souvenir tradition emerged within Jewish communities until modern times, two illuminated scrolls survive from 14th-century Egypt. Painted by the pilgrims themselves, these scrolls record their owners’ travels during the annual spring pilgrimage of Jews from Middle Eastern countries to the Holy Land.

In their format, decoration, and the selection of holy sites, these Jewish pilgrimage scrolls share many features with Hajj certificates. This close relationship is not surprising given that the Egyptian Jewish community had lived alongside their Muslim neighbors for centuries, and were familiar with their ritual practices and visual traditions. Like Hajj certificates, they also adopt a scroll form to depict a sequence of holy places rendered as a series of domed and ornamented buildings featuring arches with hanging oil lamps.

The interaction between the two religious communities is also seen in the crescents which appear atop several of the shrines. In the Princeton Scroll, for example, the Cave of the Patriarchs (Ma’arat Hamachpela), includes a crescent at the top of its central arch, indicating that it is deemed holy and thus a site of worship not only for Jews, but also for Muslims.

Kanisat Musa, Florence Scroll, 13th century, parchment, 10.7m x 17.5cm (BNCF Ms. Magliabecchiano III, 43)

The illustrations and texts of the Florence Scroll (named after its eventual place of discovery) record the journey of its maker, a 14th-century Jewish Egyptian painter, to over 130 holy sites throughout Egypt and the land of Israel. Among the many depicted landmarks is Kanisat Musa, associated with the biblical figure of Moses and considered one of the holiest places for the Jews of Egypt in the Middle Ages. Kanisat Musa is shown from two perspectives—the entire compound, framed by a wall, is seen from above, while the internal spaces and furniture are represented in a horizontal perspective. This multi-perspectival approach, similarly seen in Hajj certificates, along with the ornamental repertoire used to delineate the painted monuments (including pointed arches with hanging oil lamps and braided and interlaced ribbons), is indebted to the broader visual culture in which it was produced.

Detail of pilgrims’ inscriptions in Hebrew (above) and Italian inscriptions (below), the latter likely added at a later date, Kanisat Musa, Florence Scroll, 13th century, parchment, 10.7m x 17.5cm (BNCF Ms. Magliabecchiano III, 43)

Through the act of painting these two pilgrimage scrolls, the pilgrims not only documented their journeys, but also mentally revisited and recreated on the manuscript page the spiritual experience of their pilgrimage.

Much like modern souvenirs, these mementos of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish pilgrimage perpetuated pilgrims’ spiritual encounters, stimulating the reliving of the pilgrimage experience and their engagement with their faith.

Additional resources

The Byzantine Fieschi Morgan cross reliquary

Virtual Exhibition: Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage, The Nasser D. Khalili Collections

Şule Aksoy and Rachel Milstein, “A Collection of Thirteenth-Century Illustrated Hajj Certificates” in M. Uğur Derman 65th Birthday Festschrift (Istanbul: Sabanci University, 2000), pp. 73–134.

Pamela Berger, “The Dome of the Rock as the Temple in Pilgrimage Scrolls,” in The Crescent on the Temple: The Dome of the Rock as Image of the Ancient Jewish Sanctuary (Leiden: Brill, 2012), pp. 225–53.

Katja Boertjes, “The Reconquered Jerusalem Represented: Tradition and Renewal on Pilgrimage Ampullae from the Crusader Period,” in The Imagined and Real Jerusalem in Art and Architecture, edited by Jeroen Goudeau, Mariette Verhoeven, and Wouter Weijers (Leiden: Brill, 2015), pp. 169–89.

Mounia Chekhab-Abudaya, Amélie Couvrat Desvergnes, and David Roxburgh, “Sayyid Yusuf’s 1433 Pilgrimage Scroll (Ziyaratnama) in the Collection of the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha,” Muqarnas 33 (2016): pp. 345–407.

Sabiha Göluğu, “Touching Mecca and Medina: The Dalā’il al-Khayrāt and Devotional Practices,” Khamseen: Islamic art History Online, August 28 2020.

Richard McGregor, “Hajj Materials and Rites from Egypt,” Khamseen: Islamic art History Online, February 9 2021.

Luitgard Mols and Marjo Buitelaar, eds., Hajj: Global Interactions through Pilgrimage (Sidestone Press, 2015).

Venetia Porter, Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam (Harvard University Press, 2012).

Rachel Sarfati, The Florence Scroll: A 14th-Century Pictorial Pilgrimage from Egypt to the Land of Israel (Israel Museum, 2021).