Mound A, Poverty Point, Louisiana, c. 1300 B.C.E., earthwork, 710 feet long x 660 feet wide x 72 feet high (photo: courtesy of Jenny Ellerbe, 2012)

An ancient Indigenous city, 1650–800 B.C.E.

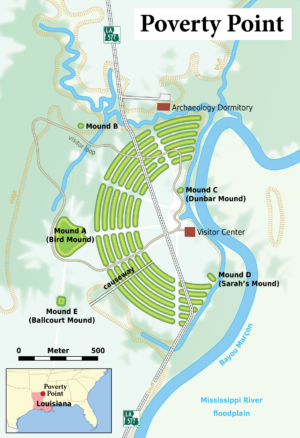

In the Lower Mississippi Valley in Louisiana, an ancient Indigenous city called Poverty Point flourished between 1650–800 B.C.E. in the Late Archaic Period. [1] The people who traveled through and settled here built several monumental earthworks including Mound A, which is a massive structure, and six curved concentric earthen ridges. The Archaic Period people of the city gathered and moved over one million cubic meters of soil to create this lived-in environment. Spread out over seven square kilometers and never faced in stone, these structures and other public works blend into the land out of which they were built. During the Mid-Archaic period, between 3500 and 2800 B.C.E., Indigenous architects and engineers designed and built with their communities the earliest earthworks in Louisiana at Watson Brake. Various settled and nomadic communities would continue to build or maintain earthworks as burial sites or meeting places into and beyond the 18th century. Outside of Columbus, Ohio contemporary Indigenous communities have successfully advocated for several ancient earthworks to be protected as World Heritage Sites along with Poverty Point. In 2022, the large magnificent earthworks at Newark, Ohio were granted this protection, and one of the largest of these earthworks, on land currently leased to a golf course, will be returned to the state of Ohio for protection as a sacred Native American monument.

In the 19th century, Mound B and Mound C were recognized as ancient monuments. Mound A, the second-largest ancient architectural structure north of Mexico, was so large and appeared to be so thoroughly integrated into the contours of the land, that as late as 1926 archaeologists believed it was a natural feature of the landscape.

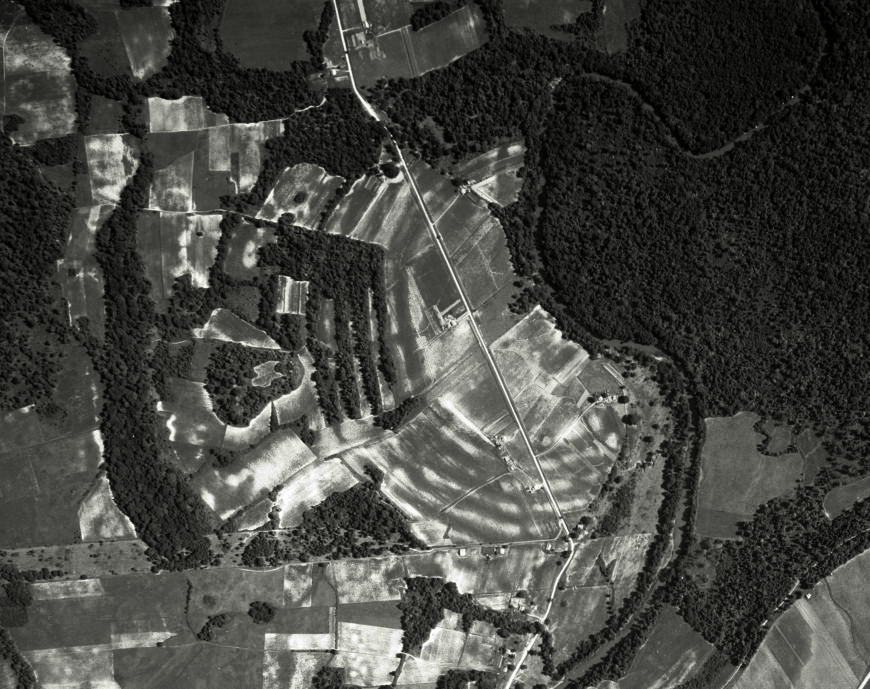

The sculpted concentric ridges that are unique to Poverty Point are low to the ground and spread out over a mile in length. Today they are worn down by time and use of the land, but still vaguely visible in raking light between the mist and the built-up ridges. Neither colonists nor archaeologists recognized these ridges as built monumental structures until the summer of 1953, when archaeologist James Ford happened to look at Army Corps aerial photographs of the region that revealed their distinct manmade composition.

Aerial photograph of the six ridges at Poverty Point, Louisiana, c. 1500 B.C.E., six semicircular earthworks, originally six feet high and three-quarters of a mile long (photo: Edgar Tobin Aerial Surveys, courtesy of P2 Energy Solutions, Tobin Aerial Archive, 1938)

The site’s history

Groups of hunter-gatherers first settled at Poverty Point in 1650 B.C.E. They would live here continuously for the next five hundred years, creating one of the most unusual cities of the ancient world: a densely populated, extensively developed settlement that lasted for five centuries without evidence of large-scale agriculture and with no evidence of an elite class. Said more plainly, this was an egalitarian hunter-gatherer community with a long-distance trade network that collectively and demonstrably shaped the land where its inhabitants lived. Amongst the most important imported objects that we find by the hundreds at Poverty Point are any kind of stone tool or ornament—from chert spear points to granite celts and slate bannerstones. Since no stone of any kind is local to this part of the lower Mississippi due to the force of the river that carved bayous into the land and would have worn away all lithic material well before it could travel into the region, all stone would have been brought into the city through trade. At its height, Poverty Point is estimated to have had a population of 9,000, a significant portion of which lived there year-round, with a varying influx of people who valued and contributed to the site’s construction and maintenance. They built these monuments within the rich alluvial floodplain of the lower Mississippi overlooking the meandering Bayou Maçon, a constant reliable source of freshwater, fish, and waterway transportation.

The six arched ridges imitate the natural arch of Bayou Maçon. Map of Poverty Point, Louisiana (underlying map © Google)

Six arched ridges

The earliest monuments built at Poverty Point were a flat-top pyramid and then two conical earthworks. Later, the inhabitants conceived and constructed the six concentric arched ridges, each originally six feet in height and three quarters of a mile long. They constructed these arched ridges as platforms where they placed hearths for cooking, leaving thousands of objects of daily life in surrounding middens. As a monumental public work, these arches are unique to the region; indeed, they are unique to all of North America.

The arched shape ridges radiate out from the narrow bottom edge of Mound A into what may have been used as a plaza-like space, leading scholars to speculate on whether Poverty Point may have been a pilgrimage site specifically structured to welcome large influxes of temporary inhabitants and visitors. The arrangement of the arches in evenly spaced rows align with the arc of the facing bayou, revealing the desire of the builders to actively engage with the topography of the land. To repeat the arc of the bayou in the shape of their manmade ridges visually and experientially established an ongoing conversation with the myriad bodies of water connected to the nearby Mississippi River. Compositionally, these six ridges were an extraordinary monumental public work collectively built that integrate the living presence of this ancient community within the landscape. This was not a wall to keep people out, but rather a set of arched ridges that linked a particular community to a particular landscape.

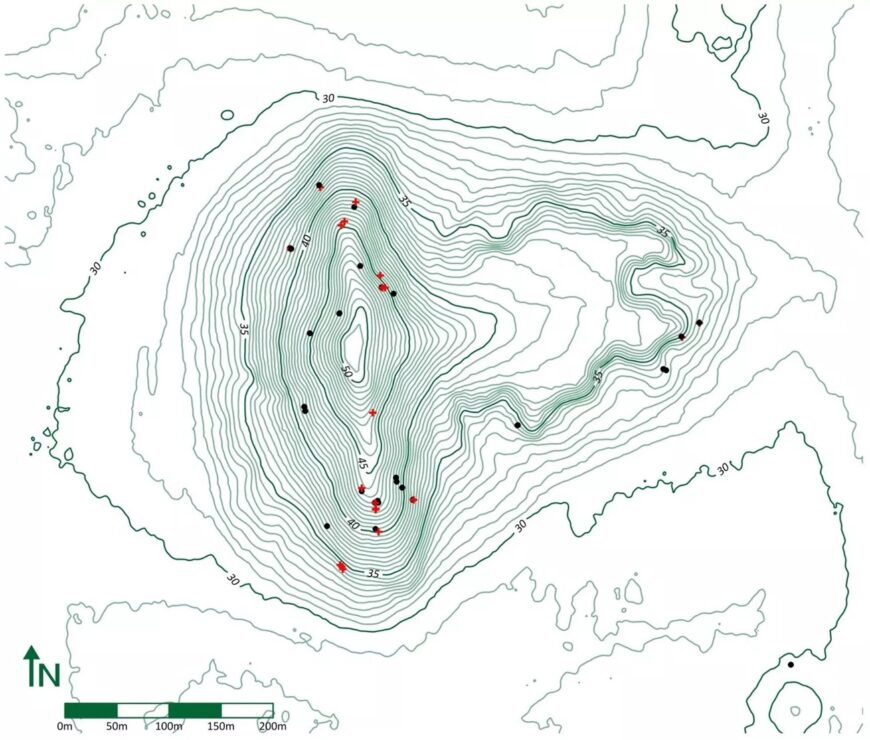

Mound A

Around 1300 B.C.E., 350 years after they began building at the site, the people of Poverty Point built their last and largest monument, now known as Mound A. Carefully placed in the center behind the arched ridges, Mound A is seventy-two feet high, 710 feet long, and 660 feet wide. At its widest it appears like a set of outstretched wings, narrowing to a point, like the beak of a bird flying west over the manmade arched ridges. It is a solid earthen structure that was built in three discernible stages. To build each stage from the base elevation up, they purposefully used three distinct kinds of soil. These soils are different in color and composition and may have been gathered and used at each stage for conceptual or structural purposes. The careful arrangement of these soils further reveals the highly organized and conscious nature of this construction. Since there was no evidence of weathering between the stages, they must have built this structure rapidly, perhaps in as little as three months, moving over fifteen million baskets of dirt to the site. There is also no evidence that they built any structure on top of Mound A or buried any individual inside. It stands as a monumental work made by and for those who chose to live here.

Stone spear tips found at Poverty Point (photo: Poverty Point World Heritage Site)

The egalitarian nature of life and the meaning or purpose of art at Poverty Point can also be seen in the even distribution of stones. 200 bowls carved out of soapstone imported from outcrops in Alabama and Tennessee were intentionally broken and ritually buried on the western periphery of the site, a location behind Mound A where the sun would set each day, suggesting an astronomical alignment. Imported stones found at the site were not the exclusive property of elites like we find at other ancient sites like Cahokia in Illinois or La Venta in Mexico; here at Poverty Point they are found in public spaces or evenly spread beneath the concentric ridges, along with baked clay forms for cooking.

An ancient society

When looked at closely and in comparison with other known ancient societies of the 1st and 2nd millennia B.C.E., such as the Olmec of Central Mexico, Poverty Point defies norms and expectations that link monumentality with elite patronage. At Poverty Point, people formed a settled society without agriculture. They built monumental architecture and earthworks without vast hierarchical divisions.

Given the importance of water for settled life in the ancient world, the settlement of Poverty Point begins with what is most conspicuously already there, that is, the Bayou Maçon itself. Together, the bayou and and natural elevation of its shoreline provided prolonged safe access to fresh water without the risk of flooding so common in the alluvial Mississippi Valley. The low, long, and arched ridges that the people of Poverty Point built are both large and inconspicuous at the same time. They are semicircular embankments built to complement daily life where people built their hearths and lived side by side. Conversely, Mound A slopes up symmetrically from behind the arched ridges into a mountainous earthen monument. On top of Mound A, the Archaic Indigenous people who lived here created for themselves an exceptional vantage point from which to look out over the arched ridges, to experience them as a visual echo of their immediate source of water. In this striking composition, manmade monuments were orchestrated to visually complement the natural contours of the land and its resources that supported them.

Map of Indigenous ancient architectural monuments (detail), Cyrus Thomas, “Distribution of Mounds in the Eastern United States,” Catalogue of Prehistoric Works East of the Rocky Mountains (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1891, plate 1)

The abandonment of the site

Approximately 150 years after the completion of Mound A, sometime between 1000 and 800 B.C.E., the people of Poverty Point abandoned the site. This occurred in a transitional period between the Late Archaic and Early Woodland Periods marked by radically increased periods of rain. And though there is no evidence that flooding occurred at Poverty Point, the rain would nevertheless have disrupted the influx of seasonal inhabitants and long-distance trade so important to the formation and maintenance of the city. Looking at Cyrus Thomas’ 1891 map of Indigenous ancient architectural monuments we can begin to see and imagine Poverty Point as one of thousands of places within the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys where Native Americans made their homes and shaped the land.

Notes:

[1] The very name “Poverty Point” tells us something of the site’s obscure modern history. In 1851 Philip Guier developed it into one of his southernmost plantations. Whereas plantations in the Middle Mississippi Valley, in states such as Tennessee or Kentucky, often had luscious names like Tulip Hill or His Lordship’s Kindness, those in the Lower Mississippi Valley, which were less reliable in the production of cotton, were often given pejorative names like Poverty Point or Hard Times Plantation. And while the archaeological site is currently a U.S. National Monument and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized for its ancient monumental architecture, it is still known by a name that marks it as a low-yield pre-Civil War plantation.

Additional resources

The Poverty Point World Heritage Site

Anna Blume, “Ancient Architecture in the Mississippi Valley: Monumentality Seen and Unseen,” RES Anthropology and Aesthetics, volumes 69–70 (2018), pp. 294–309.

Jenny Ellerbe and Diana M. Grennlee, Poverty Point: Revealing the Forgotten City (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2015).

David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Origin of Everything (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).

Tristam Kidder, “Poverty Point,” The Oxford Handbook of North American Archaeology, edited by Timothy R. Pauketat (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 464–69.

R. Clark Mallam, “Ideology from the Earth: Effigy mounds in the Midwest,” Archaeology (1982), pp. 60–64.

Anthony L. Ortmann and Tristram R. Kidder, “Building Mound A at Poverty Point, Louisiana: Monumental Public Architecture, Ritual Practice, and Implications of Hunter-Gatherer Complexity,” Geoarchaeology: An International Journal, volume 28 (2013), pp. 66–86.

Kenneth E. Sassaman, The Eastern Archaic Historicized (New York: Altamira, 2010).

Cyrus Thomas, Catalogue of Prehistoric Works East of the Rockies (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1891).