Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby: Walker explains how the molasses-covered space, along with her extensive research into the history of sugar, inspired her to create a colossal sugar-coated sphinx, as well as a series of life-sized, sugar and resin boy figurines.

Read Now >Chapter

African American art and social justice

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, 2014, at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, NY, figures made in sugar and resin © Kara Walker

At the derelict Domino Sugar Factory in New York in 2014, artist Kara Walker installed a seventy-five-foot sculpture of a sugar-coated mammy. Named A Subtlety, after a medieval delicacy, it is anything but. Walker modeled the figure’s body after the ancient Egyptian Sphinx: she reclines on all fours, her rear end propped up exposing her labia. The pose is suggestive and explicit. One hand holds a fig pose, which is tantamount to a middle finger in some cultures. The gleaming white sculpture belies the blackness of the broad nose and thick lips. The unabashed nudity (save for kerchief on her head) suggests the sexual economies of slavery that placed black women in vulnerable positions for enslavers to abuse them. Enslavers often sexually abused enslaved women and the children that resulted from that abuse would become enslaved as well.

Walker’s “Sugar Baby,” no doubt, enthralled its viewers. The pendulous breasts, ample derriere, and larger than life labia led some viewers to photograph themselves simulating sexualized poses. Those viewers mockingly reinscribed the same racist scripts of slavery’s sexual domination of black women. In a way, these reactions indicate the continued projection of slavery onto black women’s bodies and exhibit the afterlives of slavery.

The afterlives of slavery is a term I borrow from theorist Saidiya Hartman that describes the ways in which the effects of slavery still function as a life-altering force for African Americans. In Hartman’s 2016 book Lose Your Mother she says:

If slavery persists as an issue in the political life of black America, it is not because of an antiquarian obsession with bygone days or the burden of a too-long memory, but because black lives are still imperiled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago. This is the afterlife of slavery—skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment. [1]

Slavery was not a one-time event with no consequences; conversely, it is a continuing epoch that lingers in the contemporary moment with devastating effects. For this reason, slavery as a subject matter and a theme is prevalent in African American art. We are still dealing with slavery’s deleterious consequences and artists are responding to them. This chapter will address how slavery continues to resonate in contemporary African American art and how it is connected to social justice movements.

In 1968 civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer famously said:

You see the flag is drenched with our blood. Because you see so many of our ancestors was killed because we never have accepted slavery. We’ve had to live on it, but we never wanted it. So we know that this flag is drenched with our blood.Fannie Lou Hamer [2]

Faith Ringgold, The Flag is Bleeding #2 (American Collection #6), 1997, acrylic on canvas, painted and pieced border, 193 x 200.7 cm (Pippy Houldsworth Gallery) © Faith Ringgold

For many citizens, primarily those who are white, of the United States, the flag is a potent symbol of liberty and freedom. However, for African Americans that same symbol is loaded with conflict and an unsettled relationship to citizenship in the United States. African American artists have used the flag, not as a symbol of liberty and freedom, but as a symbol of a cruel despot. Faith Ringgold does this eloquently in several works over the course of her career, such asThe Flag is Bleeding (1997). In each instance, Ringgold is addressing the promises of citizenship (granted only in 1868 by the 14th amendment) to African Americans that has been denied through de jure racial segregation and subsequent de facto racist policies. The irony inherent in Flag for the Moon is that while the United States was advancing technologies to put a man on the moon, it remained tied to the past in its racial policies, in effect leaving African Americans to suffer and die.

Left: David Hammons, America the Beautiful, 1968, body print with silk screen (Oakland Museum of Art) © David Hammons right: David Hammons, Boy With Flag, 1968, body print with silk screen, 40 1/4 x 30 1/4″ (courtesy of Tilton Gallery, New York) © David Hammons

Another artist who uses the flag of the United States as a symbol of a despot is David Hammons. In America the Beautiful (1968) and Boy with Flag (1968) (among others), Hammons combines his signature body prints with the stars and stripes of the United States’s flag. The latter composition tells the narrative of Black Panther co-founder, Bobby Seale, who was barbarically bound and gagged in a courtroom trial to keep him from speaking out in his own defense. The restrained, body-printed figure is surrounded by a flag that not only provides a visual constraint to the body, but also an ideological one. The black body under the rules of the United States is not free.

David Hammons, African American Flag, 1990, canvas and grommets, 149.9 × 240 cm (MoMA)

Hammons’s many flag images culminate with African American Flag (1990), in which the artist replaces the red, white, and blue of the flag with the red, black, and green of the Pan-African flag. African American Flag encapsulates the syncretism of black people’s cultural and political investment in Pan-Africanism in the United States. Because of slavery and continued injustice, black people have a weary relationship with the flag and desired to align themselves with the struggles of Africans worldwide.

Watch videos about art with different meanings

Benny Andrews, Flag Day: Concerns of visibility, equality, and voice are present in Andrews’ Flag Day.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Slavery, abolition, and emancipation

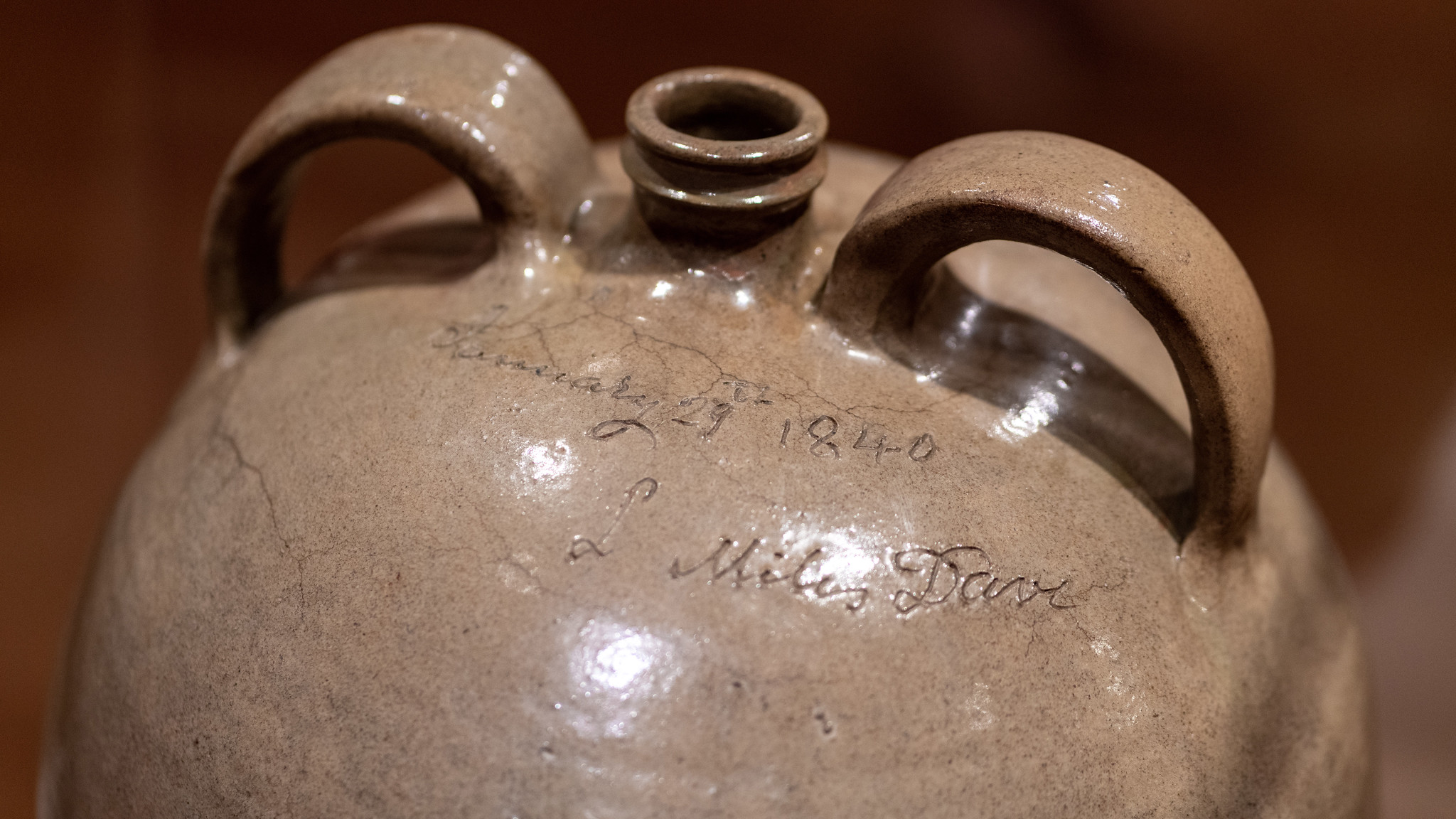

David Drake, Doubled-handled Jug (Lewis J. Miles Factory, Horse Creek Valley, Edgefield District, South Carolina), 1840, stoneware with alkaline glaze, 44.13 x 35.24 cm (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The reason black artists have come to symbolize the flag as an enemy is because of centuries of legal bondage and its long aftermath. While the founding fathers enshrined liberty and freedom into the United States’s founding documents, it was a spurious promise for African Americans. During enslavement, black artists resisted its dehumanization and brutality. South Carolina potter, David Drake, wrote poems on his large vessels that not only identified him as a master of his craft, but also as literate during a time when it was illegal for black people to know how to read. Enslavers reasoned that illiterate black people would be less likely to rebel.

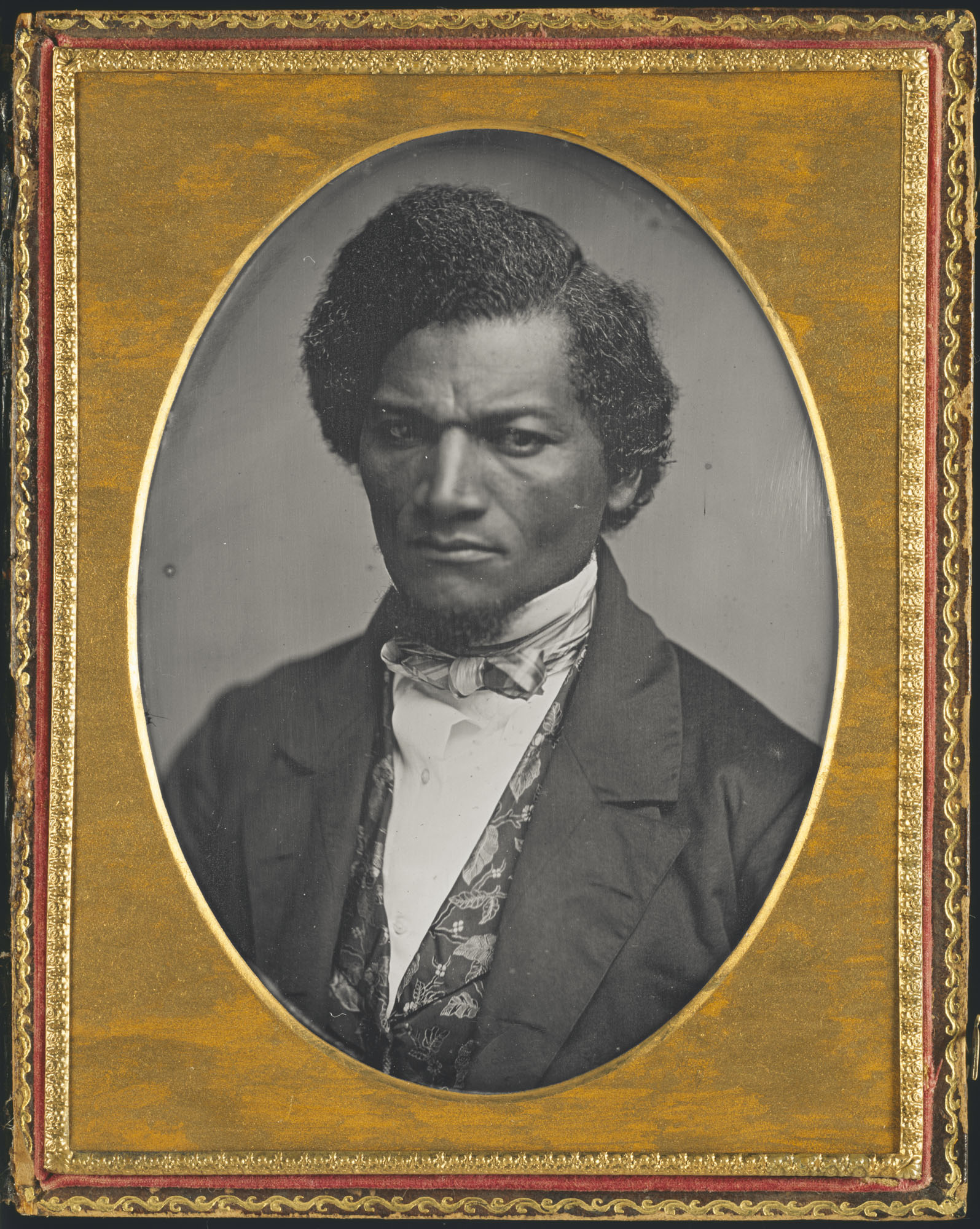

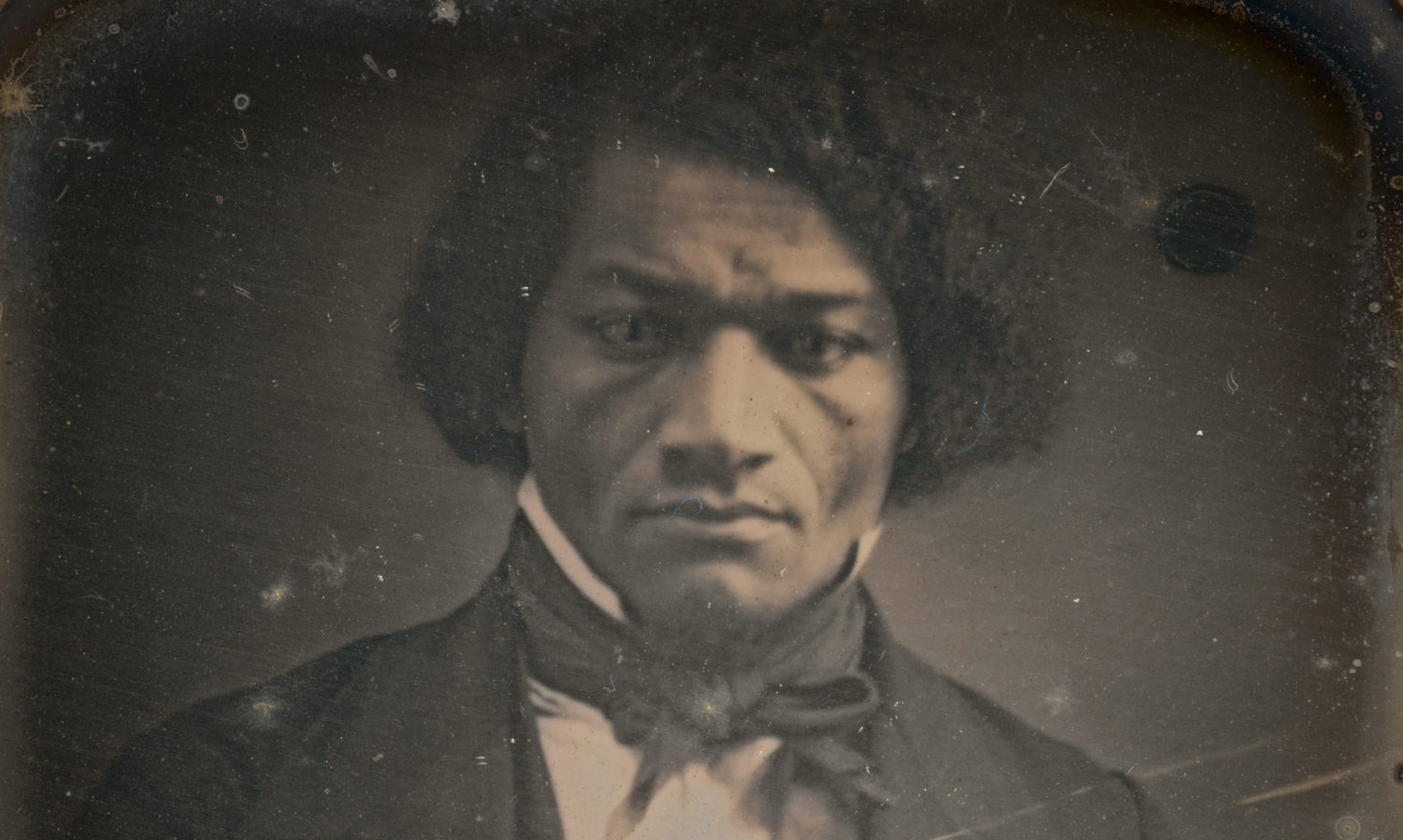

Samuel J. Miller, Frederick Douglass, 1847–52, daguerreotype, 5 1/2 x 4 1/8 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

Another enslaved man who resisted was Frederick Douglass, who escaped bondage and freed himself. He was the most photographed man of the nineteenth century and coupled with his gripping autobiography, he made the case for the abolition of slavery. Douglass was one of many abolitionists, including Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Henry Bibb, who also escaped slavery. Abraham Lincoln eventually issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, ending enslavement in the United States.

Edmonia Lewis, a free woman from New York of African and Native descent, sculpted Forever Free (1867) to commemorate the event. The gleaming white, marble sculpture consists of two African American figures: a kneeling woman and a standing man holding shackles. Their faces are lifted toward the sky, thanking god for liberation.

Watch a video and read an essay about slavery, abolition, and emancipation

David Drake, Double-handled jug: Enslaved artist David Drake inscribed a poem onto this jug at a time when literacy among enslaved people was outlawed.

Read Now >

Images in a divided world: Images played a central role in the debates over slavery and Black citizenship that consumed the United States in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Read Now >

Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free (Morning of Liberty): Sculpted in 1867, Forever Free is positioned between and among three events that forever changed the trajectory of African Americans and the United States.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Subverting the white gaze, post-emancipation

After slavery ended, the United States had a difficult time accepting black people’s freedom. There were debates about the proper role of black people in American society. Some white people could not imagine black people in any role other than as slaves. During this period there was a proliferation of images of black people as subhuman and in subservient roles. Blackface minstrelsy was also popular and trafficked in harmful stereotypes of black people. The rise of branding images, such as Aunt Jemima, held black people in perpetual servitude.

Thomas E. Askew, “Four African American women seated on steps of building at Atlanta University, Georgia,” 1899 or 1900, matte collodion silver print, untitled photo in album (disbound): Negro life in Georgia, U.S.A., compiled and prepared by W.E.B. Du Bois, v. 4, no. 362 (Library of Congress)

Subverting these images was the goal of black image makers during this period. They wanted to produce images that showed the inherent dignity of black people. NAACP founder W.E.B. DuBois championed an art that could be propaganda to ameliorate conditions for black people in the United States. He commissioned images from Thomas E. Askew that would be like positive advertising, casting black people as human, rather than the racist caricatures seen in popular media. One particular image of women sitting on steps at Atlanta University dressed in finery and demurely posed functions in this way.

James Van Der Zee, Couple, 1932 (printed 1974), gelatin silver print, 18.73 x 23.97 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art) © Estate James VanDerZee

James Van Der Zee’s images function similarly. In one, he positioned a black couple in fashionable raccoon coats in front of their car, extravagantly displaying their wealth.

Watch videos and read essays about subverting the white gaze, post-emancipation

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson: Tanner’s trip to North Carolina opened his eyes to the poverty of African Americans living in Appalachia.

Read Now >

Hale Woodruff, The Banjo Player: Woodruff reimagines racist tropes of Black banjo players with a figure who is confident and joyful.

Read Now >

Beauford Delaney, Marian Anderson: Delaney celebrates the famous opera singer Marian Anderson as a modern icon of Black excellence and civil rights.

Read Now >

Aaron Douglas, Aspiration: This was one of only two panels to survive the Texas Centennial where it pointed to a future that transcended the racism of the day.

Read Now >

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series: Lawrence carefully documents the migration of African Americans from the agricultural South to the industrial North.

Read Now >

Romare Bearden, Factory Workers: During World War II, racism flourished in the United States even as the war effort sought to bring people together.

Read Now >/6 Completed

White terror and black survival

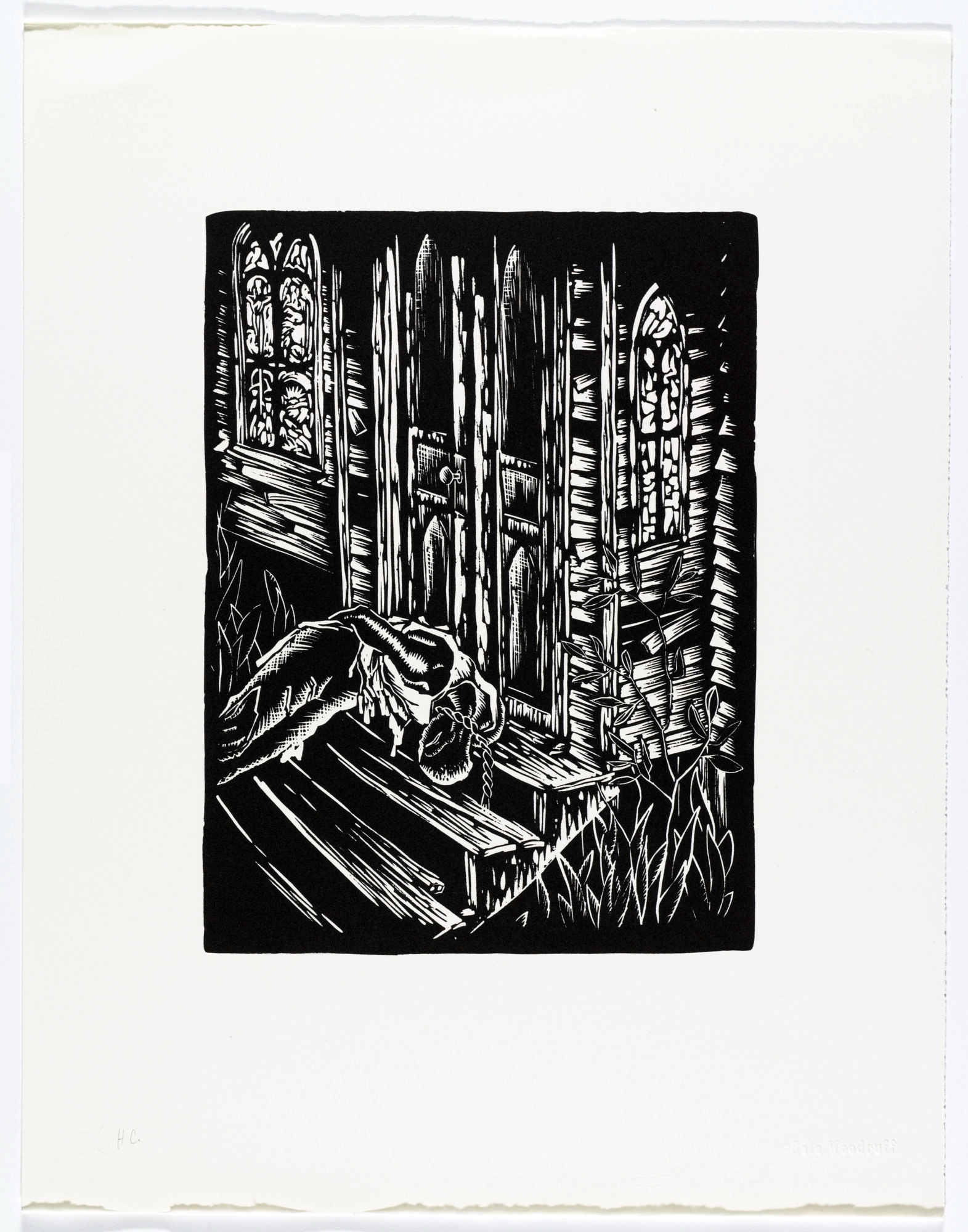

Hale Aspacio Woodruff, By Parties Unknown from Hale Woodruff: Selections from the Atlanta Period 1931–1946, 1931–46, published 1996, from a portfolio of eight linoleum cuts, image: 30.5 × 22.7 cm, Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, New York (MoMA)

The effect of having dehumanizing images of black people in the public imaginary goes beyond superficial public relations. Systematically dehumanizing black people led to their deaths. As such, the extrajudicial murders of black people were common in the United States South. As recorded in historical statistics of the United States, “Between 1901 and 1929, more than 1,200 African Americans were lynched in the South. Forty-one percent of these lynchings occurred in two exceptionally violent states: Georgia (250) and Mississippi (245).” [3] A bill introduced in April 1918 called for legal and financial ramifications for lynch mobs. The NAACP supported bill failed to gain support and was not passed. As recently as 2021, anti-lynching bills have been brought before the United States’ Senate with no success: senators failed to pass the Emmett Till Antilynching Act until 2022. [4]

Lois Mailou Jones, Meditation (Mob Victim), 1944 (private collection) © Lois Mailou Jones

Hale Aspacio Woodruff’s By Parties Unknown (1935), Lois Mailou Jones’s Meditation (Mob Victim) (1944), and “There were lynchings,” which is panel fifteen of Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series (1940–41), all deal with the racial trauma of lynching.

Jacob Lawrence, “There were lynchings,” panel 15: The Migration Series, 1940–41, 60 panels, tempera on hardboard, 30.48 x 45.72 cm (Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.)

Lawrence’s painting addresses the ways in which some black people survived in the face of that trauma: through migration to urban areas in the northern and western United States, often facing similar racist circumstances. Lawrence’s sixty-panel series outlines the causes and effects of the Great Migration, which included economic and social factors. The searing painting depicts a seated, solitary figure with his back turned to the viewer. A noose hangs on a forlorn, barren bough above him. The grief of the figure is palpable as we witness the fallout from a lynching.

Extrajudicial killings of black people still occur with shocking frequency. The high-profile 2012 murder of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman (and his subsequent acquittal) initiated the rallying cry and movement “Black Lives Matter.” Michael Brown’s 2014 murder by Ferguson police also propelled the movement forward. However, 2020 was a flashpoint with the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd causing protestors to take to the street in droves in cities across the United States. Corporations pledged money and promises of racial equity within their ranks. Quaker, in particular, pledged to stop using Aunt Jemima as a branding image and changed its name to Pearl Milling Company, while also donating millions to social justice efforts. Like their mid-century counterparts, contemporary artists continue to respond to these tragedies.

Vanity Fair cover (Sep 2020) featuring Amy Sherald, Breonna Taylor, 2020 (Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., and by the Speed Museum in Louisville, KY)

Amy Sherald painted a portrait of Breonna Taylor for the cover of Vanity Fair in 2020 and donated the proceeds to the University of Louisville to fund the Brandeis Law School’s Breonna Taylor Legacy Fellowship and the Breonna Taylor Legacy Scholarship for undergraduates. In Sherald’s portrait we see an ethereal Taylor in a luxurious blue gown that Sherald commissioned for the painting. The figure’s skin tone is Sherald’s characteristic grisaille.

Watch videos and read essays about white terror and black survival

Vertis Hayes, The Lynchers: A horrifying painting of racial violence that can help us see where we are and where we need to be in terms of tolerance and empathy.

Read Now >

Horace Pippin, Mr. Prejudice: A black painter confronts white supremacy amidst the two world wars.

Read Now >

Thornton Dial, Blood and Meat: Survival For The World: An unflinching memorial to civil rights martyrs.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Resistance through appropriation

Robert Colescott, George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook, 1975, acrylic on canvas, 84 x 108 inches (private collection) © 2017 Estate of Robert Colescott

Throughout the racial trauma and continued subjugation during the 20th century, black people have been able to cultivate moments of deep introspection and searing critique about their place in the United States using some of the very modes of visual derision white people have used against them. Some of those modes include stereotypes of black people, such as the mammy, the pickaninny, and the sambo, but their appropriation is satirical. In their original formats, as cartoons, memorabilia, and so forth, these caricatures of black people serve to mock and dehumanize, but black artists have found them to be powerful means of critiquing white supremacy. Robert Colescott’s George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook (1975) is a parody of one of the most recognizable paintings in American art: Emmanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851).

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851, oil on canvas, 378.5 x 647.7 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Leutze’s version romanticizes a pivotal moment in the Revolutionary War, while Colescott’s version showcases a motley crew of black caricatures in all manners of drunken depravity, however in similar poses. Colescott wanted to draw attention to the ways black people are tokenized in American history, but even more crucial, the ways in which the white gaze suppresses black people’s identities using a racist shorthand.

Watch videos and read essays about resistance through appropriation

Betye Saar, Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Beyte Saar boldly attempts to rescue the Mammy character from her demeaning, servile role in Jim Crow fantasy in this powerful assemblage.

Read Now >

Robert Colescott, I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees De Koo: Colescott asks—what are the implicit messages about Black womanhood embedded in American visual culture?

Read Now >

Stefanie Jackson, Bluest Eye: Taking its name from Toni Morrison’s debut novel, this painting shows the clash of innocence and the adult violence of bigotry and hatred.

Read Now >

Kara Walker, Darkytown Rebellion: Walker’s installation builds a world that unleashes horrors even as it seduces viewers.

Read Now >

Alison Saar, Topsy: Jason and the Golden Fleece and the American anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, combine to upend our own contemporary myths.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Conclusion: Reckoning with the past

Kehinde Wiley, Rumors of War, 2019, bronze, 8.2 m tall x 4.9 m long (Richmond Museum of Fine Arts, Virginia)

In the afterlives of slavery, artists play an important role as communicators of this trenchant legacy, and as we saw in Sherald’s case, activists. As part of a racial reckoning in 2020, municipalities began to examine the place of Confederate monuments in the memorial landscape. For black people, these monuments are sobering reminders of those who wanted black people to remain in bondage. The Confederates honored in the monuments were essentially traitors, but somehow, they are enshrined within American history as heroes. Ironically, the army that the Confederates fought against named several military bases after these seditious Confederates. These bases are currently in the process of being renamed. The majority of Confederate monuments were not raised in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, but were erected decades later as rebellious symbols meant to quell civil rights activism and keep black people in their place. They were symbols for the way things should have been—with black people in perpetual servitude.

Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War (2019) addresses this history with an equestrian portrait of a black man. Wiley is known for his large-scale portraits of black people that rewrite art histories by placing the black figure in compositions normally reserved for the white elite. In Rumors of War he is again placing the black figure in a space he would not ordinarily occupy. The sculpture interrogates our notions of who gets to be memorialized and how we should remember the past.

Watch videos about reckoning with the past with memorials

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice (Equal Justice Initiative): The first monument to commemorate the over 4,000 African Americans who were lynched in the early 20th century.

Read Now >

Kehinde Wiley, Rumors of War: A monumental solution to rethinking the Confederate sculptures of Richmond.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Alison Saar, Swing Low: Harriet Tubman Memorial, dedicated November 13, 2008. 13 feet (H), bronze and Chinese granite (photo: Jim.henderson, CC0 1.0)

Memorials are one way of reckoning with a violent and tumultuous past. Remembering figures, such as abolitionists, like Harriet Tubman in Alison Saar’s Swing Low (2008), we are not only remembering but also forging a path forward into the future in her likeness. Saar intended for the memorial to inspire future generations with Tubman’s heroic deeds. Tubman is shown striding forward, pulling at the roots attached to her skirt. The front of her skirt is fashioned after a cattle pusher on a locomotive. So, she is likened to a machine pulling at the roots of slavery. Her skirt also has images of faces, footprints, and objects that would have been carried by fugitives. It is through memorials such as this one that the stories of the enslaved become visible in the public sphere—and perhaps through them we can reckon with the continued legacies of slavery.

Notes:

[1] Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), p. 6.

[2] Fannie Lou Hamer: ‘The flag is drenched with our blood’, from ‘The Heritage of Slavery’ – 1968.

[3] “Anti-lynching legislation renewed,” History, Art & Archives: nited States House of Representatives.

Key questions to guide your reading

Why does slavery continue to resonate as a theme in twenty-first century art?

How do African American artists envision social justice?

Do we see resistance during the period of slavery in art? How is it imagined?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhy does slavery continue to resonate as a theme in twenty-first century art?

How do African American artists envision social justice?

Do we see resistance during the period of slavery in art? How is it imagined?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Abolition

Afterlives of Slavery

Caricature

Emancipation

Grisaille

Mammy

Memorial

Stereotype

Learn more

Contemporary Monuments to the Slave Past.

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York : Oxford University Press, 1997).

Rebecca Peabody, Consuming Stories: Kara Walker and the Imagining of American Race (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016).