Ndebele ijogolo: Ndebele arts often feature geometric forms, blocks of bold colors with black outlines, and white backgrounds.

Read Now >Chapter

Art, Adornment, and Identity in Africa

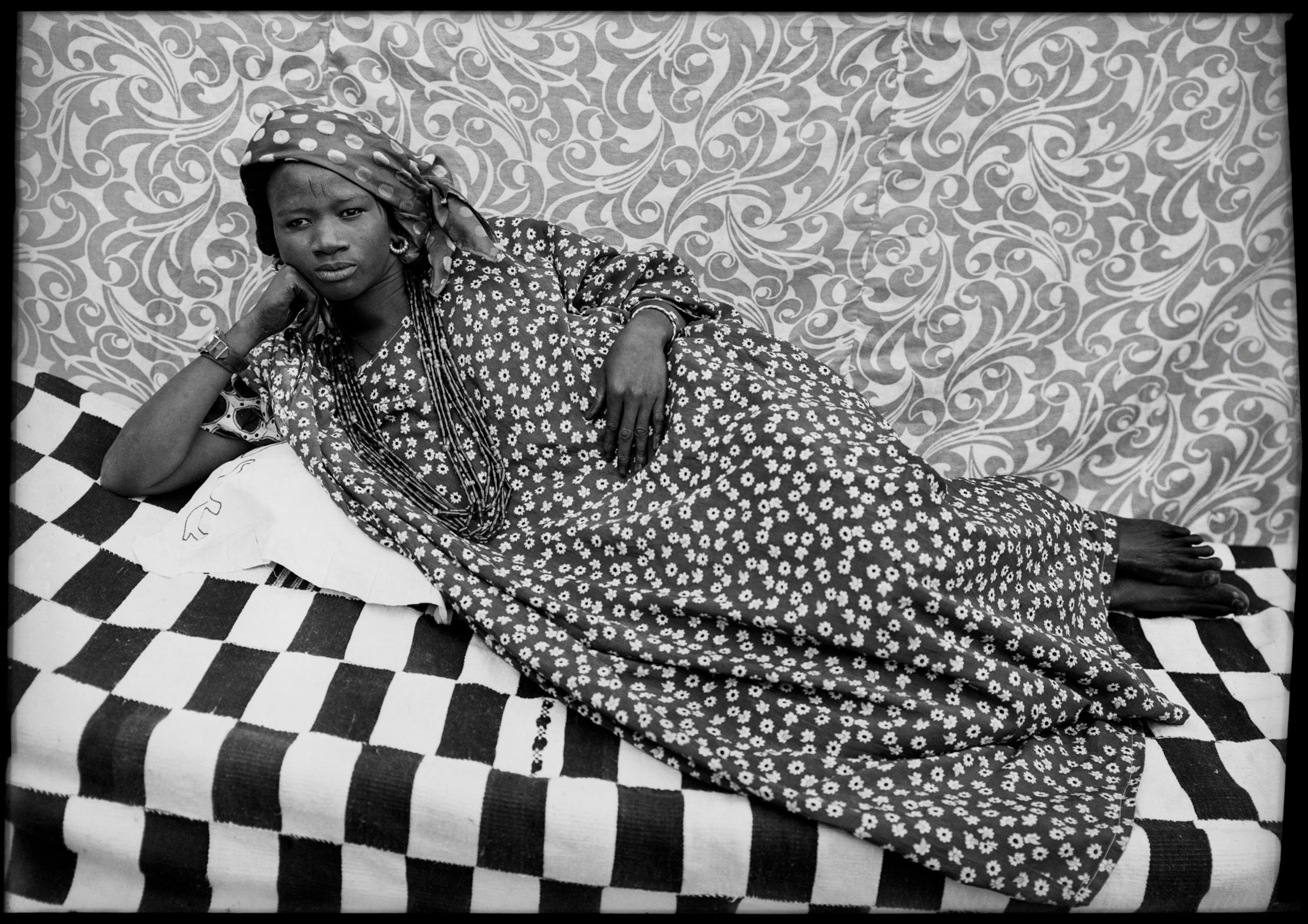

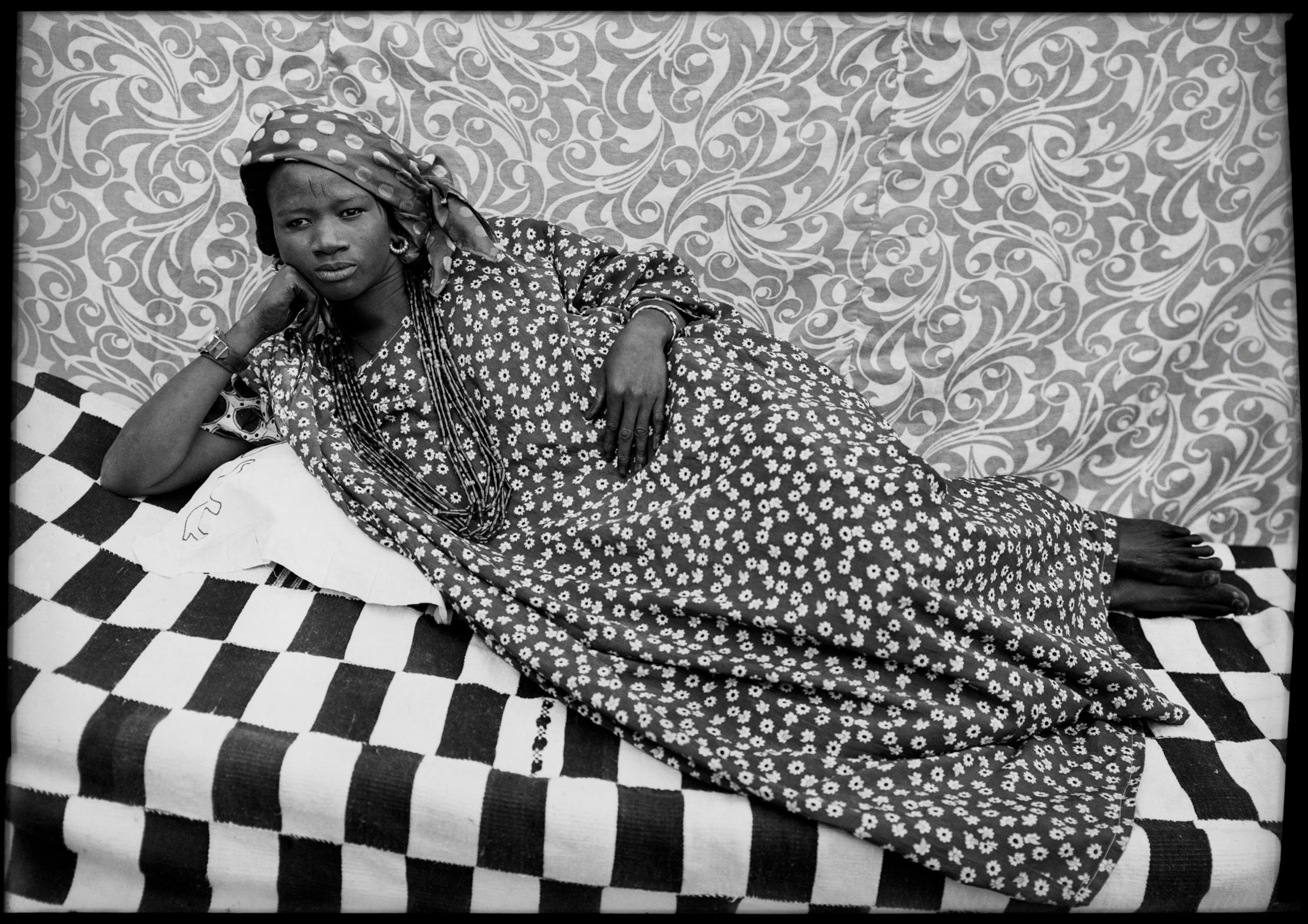

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1956–57, gelatin silver print, 39.1 x 55.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Throughout history, art has been used to express one’s sense of self and reflect the worldviews of artists, patrons, and communities. Whether asserting individual and social status, cultural identity and affiliation, or interaction and exchange, the visual arts are a powerful communication device that has been recognized and utilized by artists and audiences from prehistory through the present. As a visual language, artists have relied on the formal elements of art to construct complex messages that are interpreted and reinterpreted across time and place, and which allow viewers an opportunity to gain insights into specific contexts from our global experience. When turning to the African continent, one can find countless examples of how the visual arts have helped—and continue to help—individuals establish frameworks for negotiating and defining identity, and provide alternate approaches to documenting human interaction while promoting agency of individual expression.

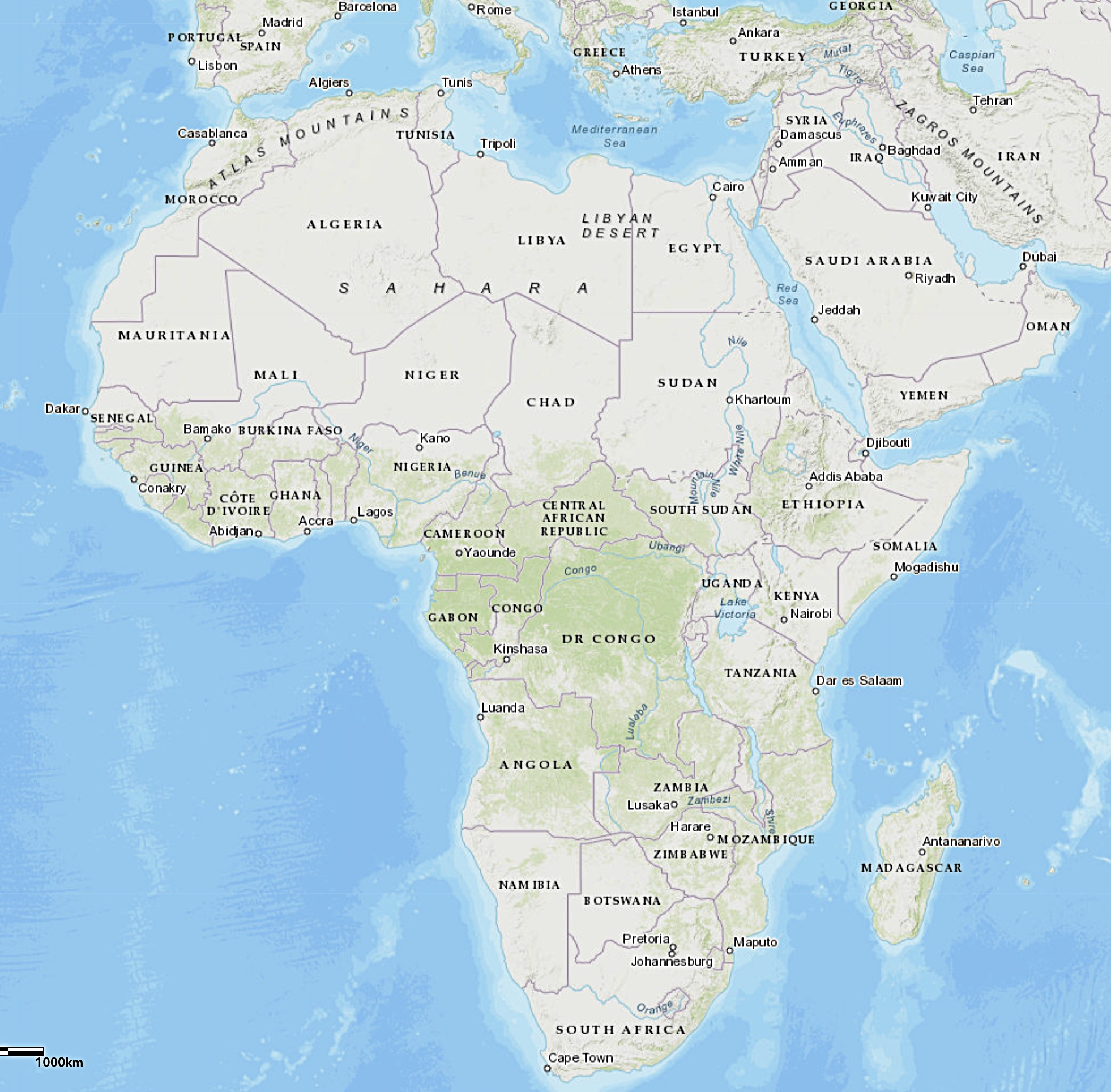

Map of Africa (Harvard WorldMap)

Cultural identity and affiliation

The use of the arts as an expression of group identity across the African continent is not a new concept. Archaeologists, anthropologists, and art historians have long understood that the visual arts often include repeated codes of cultural symbols which can communicate social messages and assert notions of status and belonging, while also highlighting communal and artistic exchange.

Ndelebe artist, Marriage apron (itjogolo or ijogolo), 1920–40 (Mpumwanga, South Africa), leather, glass beads, fabric (Newark Museum of Art)

Ndebele arts

An example of this can be found among the arts produced by Ndebele artists residing largely in the present-day Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces of northeast South Africa. Ndebele populations experienced conquest and dispossession in the mid-1800s as Boer emigrants (descendants of Dutch-speaking European emigrants to southern Africa who settled across the southern African interior from the 17th–19th centuries) moved northward from the Cape Colony and began to settle in the interior of southern Africa, including land upon which Ndebele populations had resided since the 17th century. In spite of this, Ndebele peoples relied upon the visual arts to maintain and express their cultural identity and assert a sense of continuity within a changing situation.

Ndebele arts often feature recognizable visual conventions, including the use of geometric forms, blocks of bold colors with black outlines, and white backgrounds. Furthermore, Ndebele individuals create unique artforms that assert both their cultural belonging and individual identity. For example, older married women have promoted their social standing by wearing aprons called ijogolo and amaphotho. While the aprons themselves assert one’s social identity and status, the distinctive colors and patterns of the beadwork equally reflect their broad cultural affiliation.

South Sotho beadwork

South Sotho populations in South Africa and Lesotho also use the visual arts to express belonging and identity. Although South Sotho-speakers have long lived within 150 miles of Ndebele populations, their arts of adornment display completely different visual forms and imagery. South Sotho beadwork (as shown in this thethana) shows minute visual details expressing specific genealogy and family lineage. Compared to examples of beadwork created by Ndebele artists, we see completely different forms—a fringed waist skirt as opposed to a broad leather apron—and the use of color and compositional devices is strikingly distinct, allowing the object to communicate the wearer’s status and affiliation at a glance. Furthermore, South Sotho individuals familiar with this visual language would be able to “read” the beaded adornments of others within the community and ascertain the age, marital status, education, and familial line of the wearer.

Watch videos and read essays about individual and social status

South Sotho thethana: The use of color and compositional devices in South Sotho beadwork is strikingly distinct.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Individual and social status

In addition to expressing group identity and affiliation, visual arts and adornment are used to assert individual roles, affiliations, and entitlements, as well as the personal and socio-political status of its owner or wearer. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that local concepts of individual status and identity shift based on time and context.

Vase with Rope from Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria, c. 9th–11th century C.E., leaded bronze, 12 11/16 inches (National Museum, Lagos)

The culture of Igbo Ukwu

One example of this can be found among the arts related to the culture of Igbo Ukwu, which was located in southeast Nigeria and dates to around the 10th century C.E. The objects linked to this culture were discovered by farmer Isaiah Anozie in 1938, and they provide evidence of the earliest bronze casting in the region. Moreover, the media and symbolism also point to the historical role that the visual arts played in asserting individual status.

Evidence suggests that the remains of an individual unearthed at the burial site now known as Igbo Richard—named after the brother of Isaiah Anozie—was a person of high status, as he was covered in beads and surrounded by other objects of bronze and brass. Scholars have determined that brass objects found at Igbo Ukwu were imported, making them a valuable trade commodity. These uncommon materials were used to create objects of status, such as a chest pendant in the form of a bird and eggs. This may have suggested male power, spiritual acuity, and ones’ role in the success of future generations. Not only would the use of brass suggest status and prestige, but the added beads would have been obtained through trade and interaction.

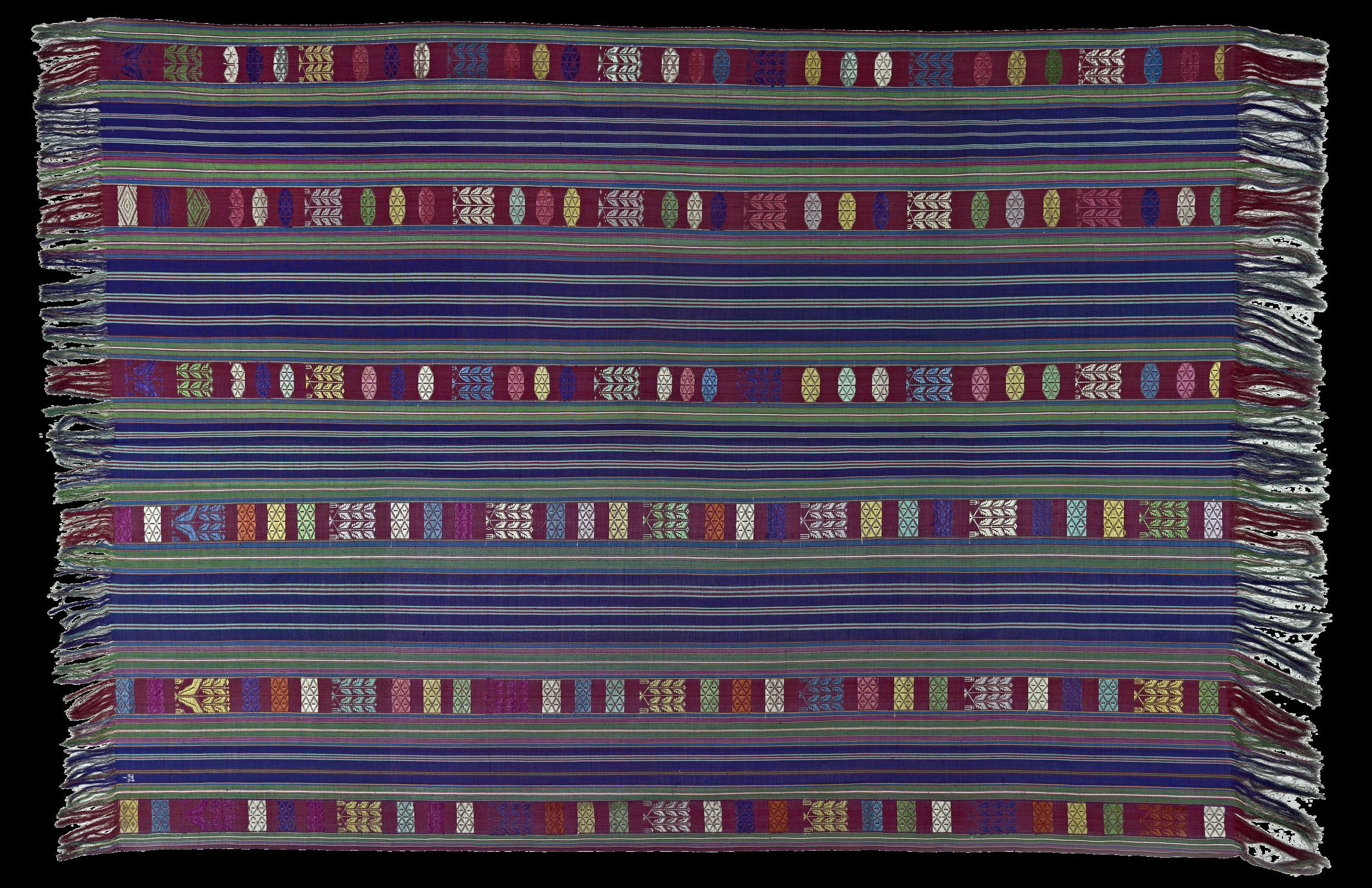

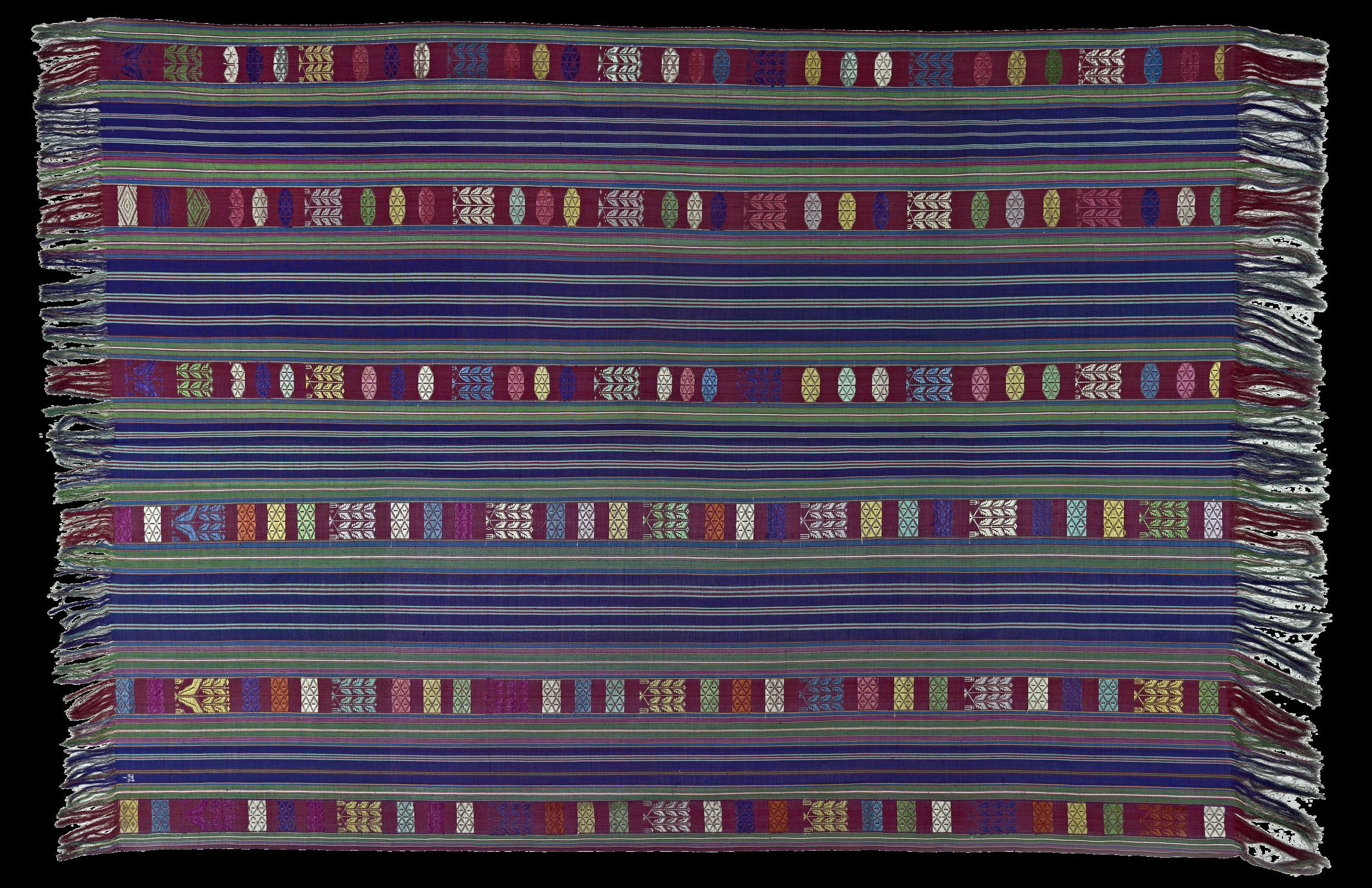

Silk textile (lamba akotofahana), 19th century (Merina peoples), woven and dyed silk, Madagascar, 225 x 147 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Silk textile (lamba akotofahana)

One also finds that objects of everyday use can be used to express individual status and can vary in meaning based on context. For example, artists across Madagascar create textiles that play important roles in maintaining social relationships, communicating ideas, and asserting status. One finds two general types of cloth used across multiple cultures and communities, widely known as lamba (cloth for the living) and lambamena (red cloth, or burial cloth). Such textiles can be used to communicate specific messages about the wearer, and may indicate one’s age, cultural identity, and national pride.

One of the most significant functions of lamba is to re-enshroud ancestors (known as razana) during the reburial season. The textiles are often very expensive, sometimes the equivalent of one month’s salary. Typically, they are replaced every few years. Not only is the re-shrouding of deceased family members recognized as a conduit of communication with one’s ancestors, but lambamena confer dignity and status upon the deceased while protecting them from polluting forces.

Paa Joe, Coffin in the Form of a Nike Sneaker, mid-1990s, wood, pigment, metal, fabric, 73.7 x 203.2 x 57.2 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Sculptural coffins

Arts of adornment can also play a role in expressing individual status through memory. While the monumental burials found in Kemet are perhaps the most well-known across the African continent, contemporary examples play a similar role in preserving and expressing notions of identity and self. An example of this can be seen in the sculptural coffins of Kane Kwei and Paa Joe. Kwei and his brother Ajetey, both of whom were working as carpenters, created a coffin in the form of an airplane to honor their recently deceased grandmother in 1951. After seeing this creation, others soon came with special requests for personalized coffins that express and celebrate the life, identity, and status of deceased individuals. As commissions increased, Kwei further developed his practice with his apprentice Paa Joe, who continues his practice in greater Accra.

While these coffins have become important status symbols in the complex funerary practices among Akan-speaking peoples, the so-called “fantasy coffins” or “proverb boxes” have taken on other meanings as they change contexts. For example, one can find coffins by Paa Joe in museum collections across the globe, being exhibited as sculpture. This example of the shifting meaning of an object as it moves across contexts perhaps raises the question of how objects and their meanings are defined in different spaces.

Amazigh ear pendants, early 20th century (Anti-Atlas Region, Morocco), silver alloy, enamel, glass, and carnelian, 34.4 x 20.3 x 2.9 cm (Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C.)

Amazigh jewelry

Like other regions across the African continent, North Africa and the Sahel has been a multicultural region marked by trade, exchange, and interaction. Examples of this can be seen through the remains of Roman architecture, the presence of Islamic and Jewish sacred spaces, and the arts of adornment created and worn by Indigenous peoples, such as the Imazighen. Today, many Amazigh individuals live in North African countries such as Algeria and Morocco, although smaller populations are also found in Niger, Mali, Libya, Mauritania, Tunisia, Burkina Faso, and Egypt. Given the dynamic and interactive nature of the region, many Amazigh arts reflect cross-cultural influences, while equally asserting local notions of power and prestige.

Examples of this can be seen in the jewelry worn by many Amazigh women, which can not only assert one’s status and cultural affiliation but serves a powerful protective function in daily life. Often given as part of a woman’s dowry, elaborate ensembles of precious metals maintain intrinsic commercial value and are also understood to contain baraka, a blessing power recognized across many Islamic societies. Thus, when worn on the body by wealthy individuals of high status, one is not only projecting notions of success and status but is also maintaining protection from debilitating forces that might hinder one’s success in daily life.

Watch videos and read essays about individual and social status

Igbo-Ukwu: The bronzes from Igbo-Ukwu have intricate designs and symbolism, and demonstrate technical virtuosity.

Read Now >

Silk textile (lamba akotofahana), Merina peoples: The lamba (generic name for cloth in Madagascar) is worn as a shawl for everyday wear, but the Merina peoples of Central Madagascar also use it as a shroud in which to wrap the dead during burial ceremonies.

Read Now >

Paa Joe, Coffin the Shape of a Nike Sneaker: Ghanaian coffins are famous for their creative shapes.

Read Now >

Workshop of Paa Joe: This wooden coffin in the form of eagle with painted gold feather markings was made in the village of Teshie in Ghana.

Read Now >

Amazigh jewelry: This jewelry communicates notions of status but also protects from debilitating forces.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Defining and expressing power dynamics

In addition to cultural and individual expressions of identity, visual arts and adornment can equally be used to communicate broad social messages to people within and beyond collective groups. Just as the aforementioned examples linked dress code with specific affiliations and entitlements, visual imagery has also been used to highlight ideologies of power, interaction, and exchange. In such cases, arts of adornment can be used to emphasize a new order of obligations or solidify existing structures of power.

Elephant mask, 1900–50 (Bamileke peoples), raffia cloth, indigo dye, glass beads, and cotton cloth, 111.2 x 48.3 x 17.7 cm (The Museum of the Fine Arts, Houston)

Bamileke kingdom

Within the Bamileke kingdom in western Cameroon, performance arts and adornment are used to express power, wealth, and belonging. This is perhaps best seen among members of the Kuosi society, which was formerly comprised of royalty, titleholders, and high-ranking warriors, and now includes wealthy members of the community. Society members perform with cloth masks mimicking the head of an elephant, which are embroidered with beads and cowry shells. The glass beads and cowries are overt symbols of wealth and largesse, as beads were formerly luxury items obtained through trade and cowries were once used as currency. Thus, when viewed during funerals and public events celebrating kingship, the masks and their performers project notions of wealth and status, while also honoring the Fon (king).

Some scholars have suggested that the specific patterns and colors found on the masks are layered with symbolism, some of which may honor the lives of the deceased, as well as the role of women in society and the office of kingship. Regardless of these potentially embedded meanings, the masks and performances provide an outlet for society members to assert their social standing and position, as well as promote the wealth and stability of the kingdom.

Plaque: Equestrian Oba and Attendants, 1550–1680 (Court of Benin, Edo peoples, Nigeria), brass, 49.5 x 41.9 x 11.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Kingdom of Benin

Using arts of adornment to express social and spiritual power is a continent-wide practice. One can find countless examples in which individuals rely on visual accouterments to express specific information about the position and status of the wearer. While the use of some arts of adornment were recently developed and adapted, other traditions have been maintained for centuries. An example of this can be seen on any number of bronze plaques from the Kingdom of Benin, Nigeria, which formerly adorned the pillars in the Oba’s (king’s) royal audience hall dating to the 16th century.

When looking at the high-relief imagery depicted in cast bronze, one finds a wealth of visual information communicating the subject’s status and social position. For example, one can recognize the central figure in Equestrian Oba and Attendants as the Oba himself, not only through his size and his elevated position upon horseback, but also through the detailed accouterments that the artist painstakingly depicted. The Oba’s columnar neck rings, textured headdress, and beaded necklaces are understood to be made of red fire coral beads, a rare and valuable trade commodity that has been part of the Oba’s royal regalia for centuries, and references his reciprocal relationship with the deity Olokun, the god of the underworld, and spiritual counterpart of the Oba’s earthly authority.

Olowe of Ise, Veranda Post of Enthroned King and Senior Wife (photo: Dr. Delinda Collier, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Olowe of Ise (Yoruba)

The depiction of status and power can also be found in more recent examples. Olowe of Ise, a renowned Yoruba sculptor who created works commissioned by rulers and political officials from multiple continents, exemplifies this through imagery featured in his depictions of Yoruba kings and titleholders. When looking at his carved Veranda Post of Enthroned King and Senior Wife, one immediately notices unique accouterments that provide a wealth of information at a glance. Although the seated king is smaller in scale compared to his accompanying wife, his political and spiritual authority is expressed through royal regalia that would be locally recognizable. The conical headpiece depicts a crown (adenla) worn by Yoruba kings who can trace their lineage back to the gods (Orisha) themselves, referencing a ruler’s earthly and spiritual authority. Adenla are understood to be filled with empowering substances that, when put into contact with the wearer’s head, modify the individual and thus provide them with greater insight and wisdom. The small bird on top of the crown also signifies status and authority, and is understood to represent the collective power of women (“Our mothers”) in society. The figures themselves and their respective accouterments present notions of power, status, influence, and balance, and offer the viewer an example of an equitable and effective ruler.

Watch videos and read essays about defining and expressing power dynamics

Bamileke elephant mask: Within the Bamileke kingdom in western Cameroon, performance arts and adornment are used to express power, wealth, and belonging.

Read Now >

Benin plaques: We get a sense of the Oba’s status through what he wears on these plaques.

Read Now >

Equestrian Oba and Attendants: This plaque depicting the Oba (king) and his imperial retinue hung outside the palace, detailing dynastic history.

Read Now >

Olowe of Ise, Veranda Post of Enthroned King and Senior Wife: The convention of elongating the figure can be seen in many of Olowe’s carvings, to visually highlight the importance of the head that holds the inner spiritual power, dignity and strength, and sacredness of one’s destiny.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Global exchange / continuity & change

While the aforementioned examples provide glimpses into the roles of adornment in specific regions, periods, and contexts, one must not overlook the impact of both continuity and change in art production across the African continent. In addition to expressing local definitions of identity, status, and power, arts of adornment equally highlight the contributions and position of African artists and patrons in global exchange. Such dynamic visual expressions of international dialogue counter false narratives of isolated, primitive societies across the continent and highlight the ever-present aspects of interaction, ingenuity, and global exchange in the arts.

Kente cloth, created by Asante weavers

Although many of the arts created across the African continent include cross-cultural visual elements, some examples also highlight the role of global exchange and interaction through their media and materials. Perhaps one of the most recognizable examples is kente cloth, a strip-woven textile created by Asante weavers in Ghana. Although kente has been locally used to express status and knowledge systems for centuries, this textile has now become an international symbol of African heritage. However, it’s global reach is not a new development. Some historical examples were created by unraveling imported Chinese and silk textiles that were obtained locally through trade with European merchants, along with Italian waste silk, and re-weaving the threads to create fabrics bearing locally significant designs. Even today, many kente patterns and motifs have specific names and may refer to individuals, plants, animals, objects, or proverbs. Like many of the visual arts produced by Asante artists, kente reflects the so-called “visual-verbal nexus,” in which visual elements refer to specific bodies of knowledge and have the ability to communicate significant information about the artist, patron, and context in which they appear.

El Anatsui, Old Man’s Cloth, 2003, aluminum and copper wire, 487.7 x 520.7 cm (Harn Museum of Art, Gainesville)

El Anatsui

Contemporary artist El Anatsui perhaps plays upon these complexities of knowledge, context, identity, and meaning in his sculptural installations found across the globe. Born in Anyako, Ghana in 1944, Anatsui studied art at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi and went on to teach at the Fine Arts Department at the University of Nsukka, Nigeria. While some of his work visually resembles kente textiles, Anatsui relies on repurposed materials such as metal liquor bottle caps and copper wire to create complex installations that draw attention to the instability and multiplicity of identity at both the local and international level.

Anatsui’s interest in exploring shifting notions centering on identity perhaps reflects his own experience as a “cultural outsider” working in Nigeria. In a similar way that individuals maintain multiple identities, Anatsui’s work equally defies a singular artistic identity, blurring the lines of specific media such as sculpture, painting, textile, or installation art. Anatsui further complicates the singular interpretation and categorization of his work by often avoiding specific instructions on how a piece should be displayed, resulting in new visual expressions each time a work is exhibited.

![Seydou Keïta, Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress], 1956, printed 1997 (Bamako, Mali), gelatin silver print, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) © Seydou Keïta](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Screen-Shot-2022-08-10-at-9.28.40-AM.png)

Seydou Keïta, Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress], 1956, printed 1997 (Bamako, Mali), gelatin silver print, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) © Seydou Keïta

Seydou Keïta

While contemporary artists like Anatsui continue to contribute to global discussions of art and identity in the 21st century by drawing upon media and materials that represent global encounters, the role of visual arts and adornment as a cross-cultural bridge is not new. Nearly a century earlier, Malian artist Seydou Keïta used the media of photography to generate equally poignant discussions of self-expression in both local and global contexts.

Although he began his career as a carpenter, Keïta was given a camera by his uncle and set up his own studio in Bamako after learning its functions. When we observe Keïta’s studio work, we are offered a glimpse into the lives of individuals who have sought to have their portraits taken and are presented with images which counter the notions of the African continent as a place of famine, conflict, and the “exotic.” In fact, one of the most sensational aspects of Keïta’s work rests in the perception that they are perhaps unsensational. The success of Keïta’s studio practice is not only reflected in the documentation of 20th-century life, but was given broader recognition through his appointment as official photographer for the Malian government in 1962, as well as the inclusion of his images in numerous exhibitions, including the 1991 show “Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art.”

Yinka Shonibare, CBE, The Swing (after Fragonard), 2001 (Tate, London) © Yinka Shonibare

Yinka Shonibare

Notions of cultural affiliation and identity continue to be asserted and interrogated in contemporary works of art from across the African continent. One example can be found in the work of Yinka Shonibare, a British born Nigerian artist who explores notions of nationalism and identity and their related instabilities. A self-proclaimed “postcolonial hybrid,” Shonibare creates works using Dutch wax cloth, a textile which has been appropriated into local West African fashion and visual culture and yet is itself a European product of Imperialism.

As the Dutch empire was attempting to reconquer Indonesia during the mid-1800s, textile manufacturers began producing imitations of Indonesian batik with hopes of undercutting the local markets abroad. However, the fabrics were largely rejected by Indonesian consumers and the venture was soon recognized as unsuccessful. Searching for a new market, Dutch designers fine-tuned their previously unwanted product to incorporate culturally relevant symbols found across West Africa and created a new demand for this European industrial product. It is against this complex history that Shonibare’s recreations of iconic European works of art question the constructs of identity and authenticity through both subject and media.

Read essays and watch videos about global exchange & continuity and change

Kente cloth: This cloth—first woven by a wise spider—sends social messages through a system of specific patterns.

Read Now >

El Anatsui, Old Man’s Cloth: Textile or sculpture? El Anatsui purposely disregards the limiting categories imposed by Western art history.

Read Now >

Seydou Keïta, Untitled (Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress): Studio photography produced mementos for the growing middle class: Keïta’s Bamako studio was abuzz with clients.

Read Now >

Yinka Shonibare, The Swing (After Fragonard): This British-born Nigerian artist brings a Rococo painting into three dimensions, changing some critical details.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Conclusion

While the works of art highlighted in this essay present only a limited glimpse of the role that objects of adornment have played in promoting local and global identities across the African continent, they speak to the larger role of art as an expression of ourselves and the world in which we live. As objects of communication, arts of adornment continue to contribute to constructions of status and affiliation, defining and expressing power dynamics, and highlighting the role of African arts and artists as negotiators of identity in both local and international contexts.