The Qing dynasty: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 52

Art of the Qing dynasty

Treasure Box of Eternal Spring and Longevity, Qing dynasty, Qianlong reign, 1736–95, carved red, green, and yellow lacquer on wood core, China, 16.5 x 44 x 44 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1990.15a-e)

During the late 1620s and 1630s, peasant uprisings swept through China’s countryside and rebel armies sacked the Ming Dynasty capital of Beijing. At that time, the last Ming emperor committed suicide. However, before a new Chinese dynasty could be established, the Manchus, who were a semi-nomadic tribe from the northeastern frontier, invaded and conquered China proper. After a particularly bloody transition, the Manchus established the Qing (“Pure”) Dynasty and set about to expand their territory, ushering in an era of political stability and economic prosperity. The Manchus became great patrons of the arts, using Chinese cultural traditions to legitimize their rule both at home and abroad.

Map of the Qing dynasty in 1890

This chapter introduces key topics in the histories of Qing dynasty art, looking at how the making of art intertwines with the politics of identity and ethnicity, from regional social circles to global audiences. It introduces art worlds both inside and outside of the Qing court (those working under the emperor), as well as relations between China and other countries (including European powers and the United States) up through the founding of the Republic of China in 1912.

Read an introductory essay about the Qing dynasty

/1 Completed

Painting after the fall of the Ming

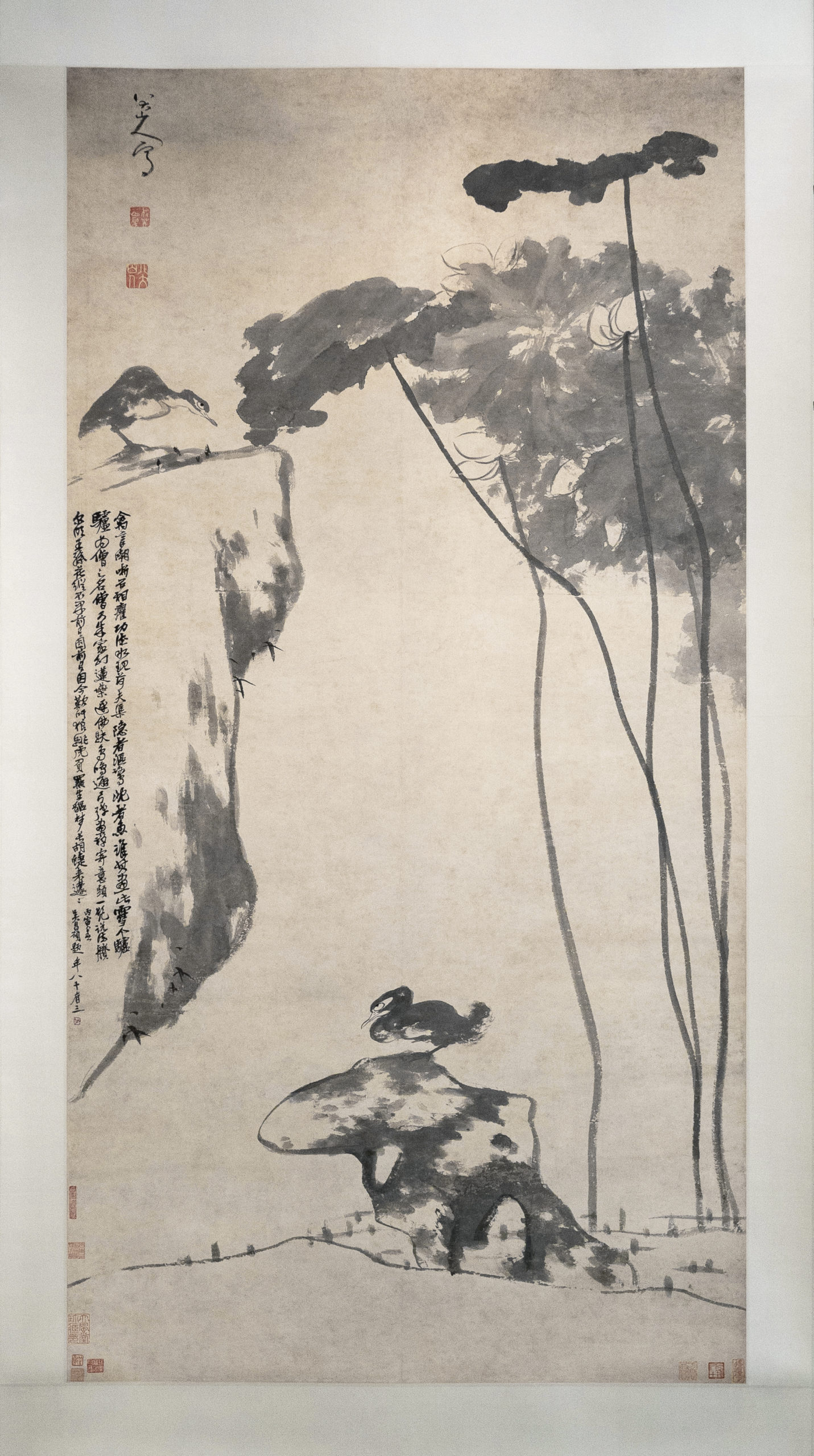

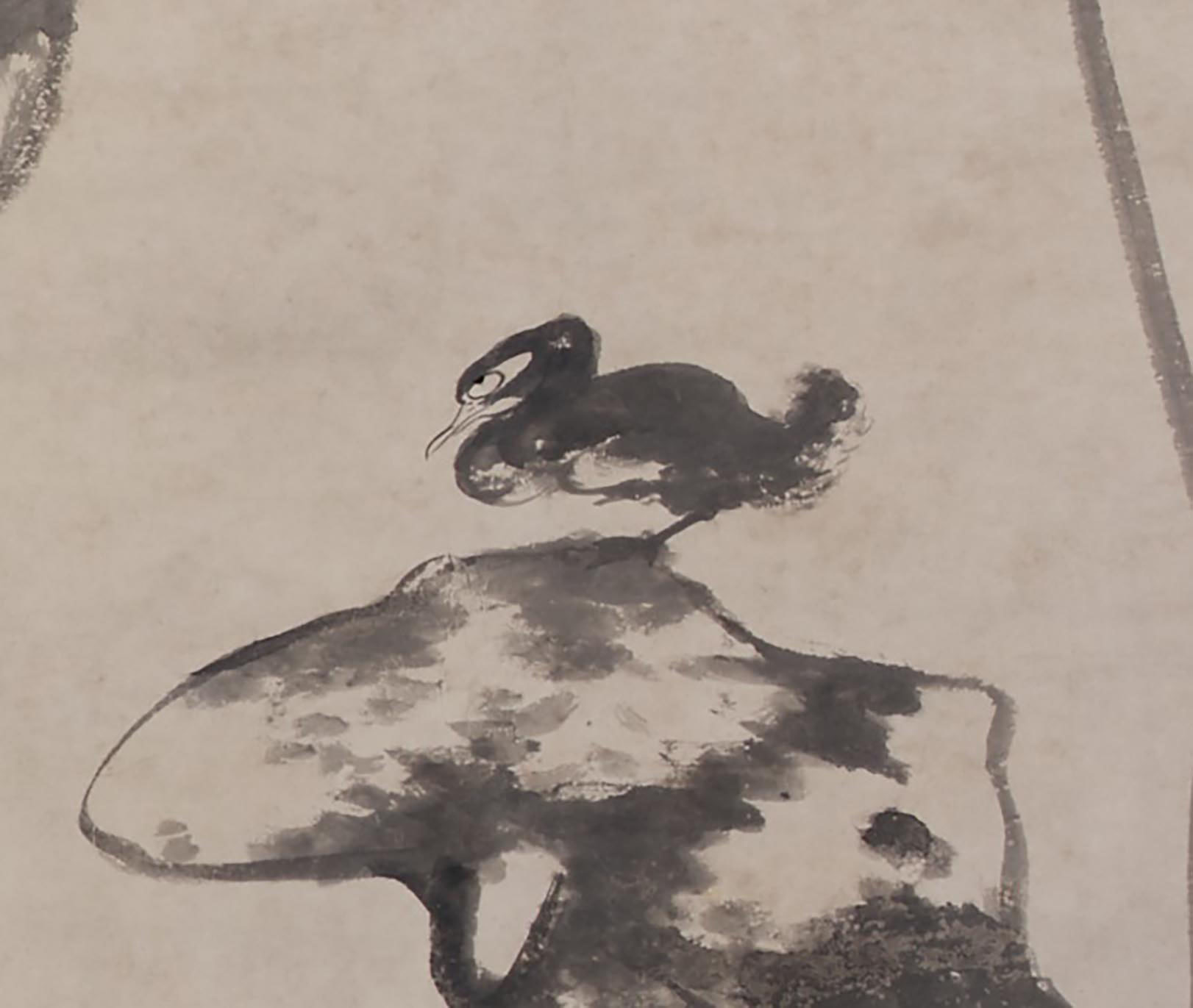

Bada Shanren 八大山人 (朱耷), Lotus and Ducks (colophon by Wu Changshuo 吳昌碩), c. 1696 (Qing dynasty), ink on paper (hanging scroll), image 185 x 95.8 cm (Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

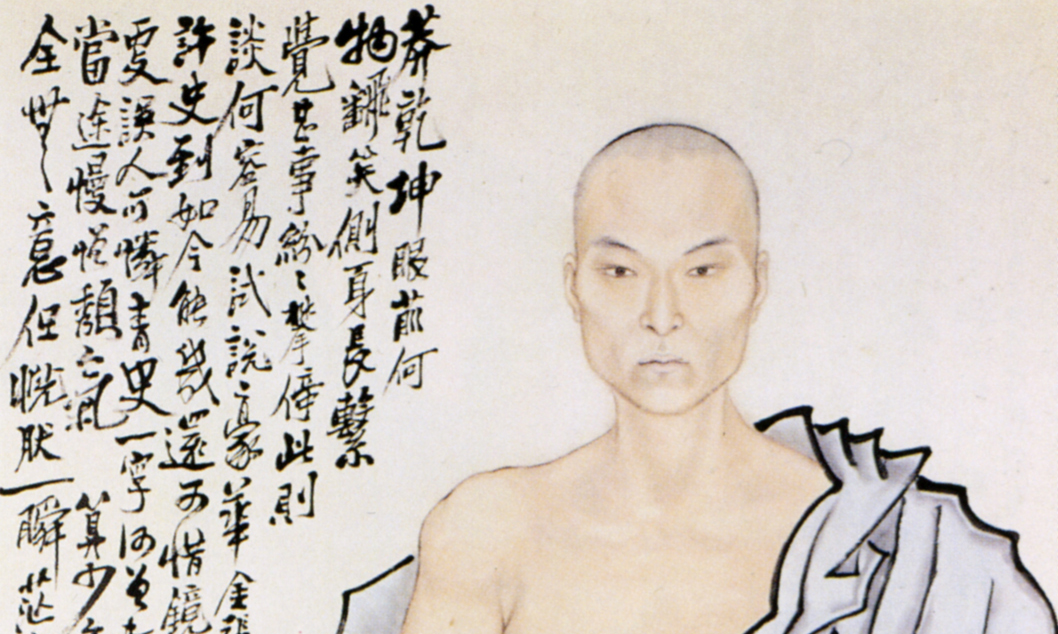

The expressive medium of painting offers insight into the tumultuous transition from the “Great Ming” to the Manchu-ruled Qing dynasty. Many Han Chinese remained loyal to the previous Ming dynasty and resented Manchu rule, particularly in Ming strongholds in the southeast. These yimin, or “leftover subjects,” often protested through art, such as the artist Bada Shanren, a Ming prince who became a monk upon the fall of the dynasty. His portrayals of birds and fish convey multiple meanings through gestures and expressions suggesting anger or frustration.

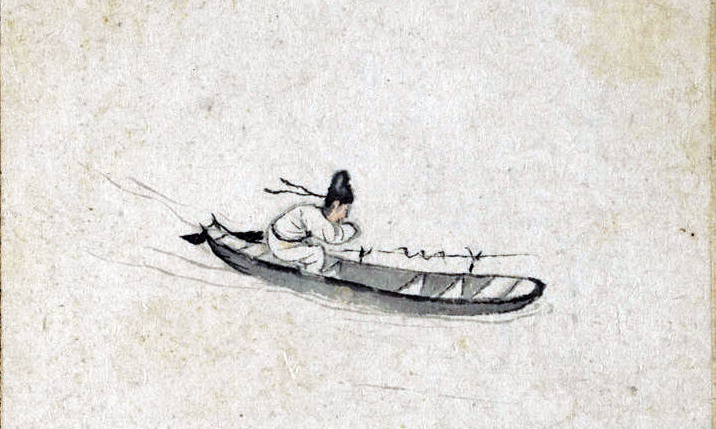

Gong Xian, one album leaf from Eight Views of Landscape, 1684, Qing Dynasty, handscroll, ink on paper (Shanghai Museum)

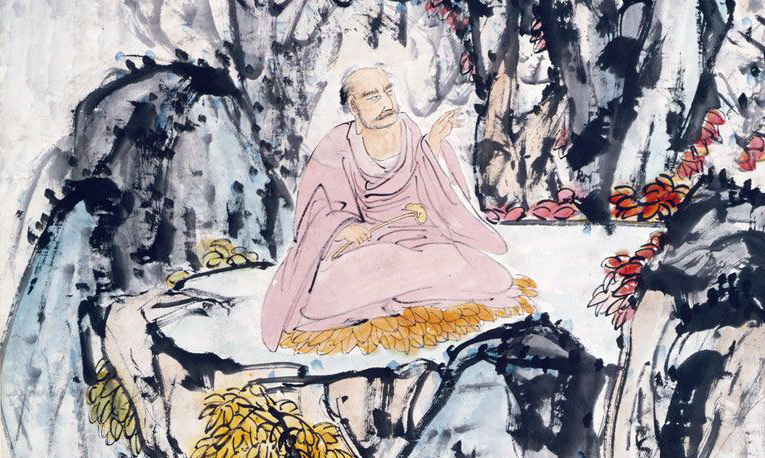

The artists Shitao and Gong Xian painted landscapes of reclusion that may feature a lone fisherman or desolate mountains—images that represented an escape from their trauma and grief over Manchu rule. Others chose to serve the Manchu court, such as Wang Shimin, but also maintained social and artistic circles outside of court devoted to the study of ancient paintings and calligraphy. Whether these artists are described as “individualists” or “orthodox” in their stylistic approaches, they represent a range of responses to the establishment of the Qing dynasty, the last era of imperial rule in China.

Watch videos about painting after the fall of the Ming dynasty

Shitao, Returning Home: An artist who asks “Who am I, and what am I supposed to do with my life?”

Read Now >

Gong Xian, Eight Views of Landscape: Nature becomes a refuge for an artist after the fall of the Ming.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Visual cultures of the Qing court

Manchu patronage gave rise to a flourishing visual culture at the court in Beijing, especially during the stability and prosperity of the eighteenth century. While the Manchus embraced Han Chinese cultural traditions as a cornerstone of their rule, they also welcomed artists, scholars, and missionaries from around the world who shaped the arts and architecture of China’s last dynasty.

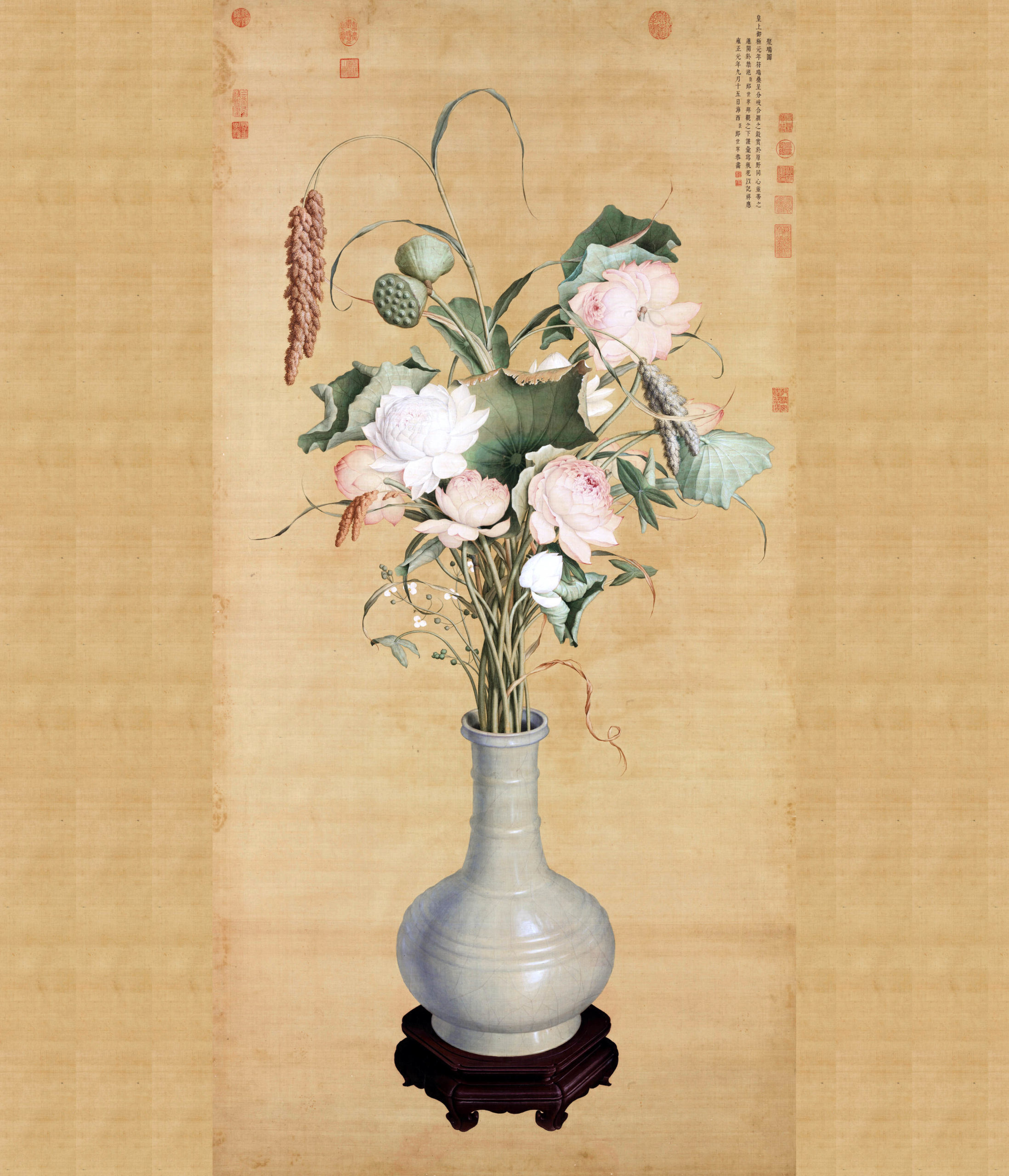

Lang Shining (Guiseppe Castiglione), Assembled Blessings, dated 1723, Qing dynasty, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 173 × 86.1 cm (The National Palace Museum, Taipei)

In one notable instance, it was said that the auspicious signs of twin lotuses and multi-headed grain stalks appeared throughout the empire when the Qianlong emperor ascended the throne. Upon studying these remarkable plants in a celadon vase in the imperial workshop, the Italian Jesuit, Giuseppe Castiglione (also known by his Chinese name, Lang Shining), rendered the image in the Chinese medium of ink and color on silk, but with the volume and spatial sensibilities associated with European art. Castiglione had come to China as a Jesuit missionary and would served at the Qing imperial court.

Giuseppe Castiglioneand Imperial workshop, The Qianlong Emperor as Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, Qing dynasty, Qianlong reign, mid-18th century, ink, color, and gold on silk, China, 113.6 x 64.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment and funds provided by an anonymous donor, F2000.4)

His fusion of Chinese and European pictorial techniques pleased imperial tastes and led to many more commissions—including a representation of the emperor in Buddhist dress. In fact, the Manchus also produced an impressive amount of Buddhist art at the court for use in their diplomatic alliances with Tibet and Mongolia. Through hybrid approaches to court dress and objects such as lacquerware and ceramics, the Manchus proclaimed their right to rule over a multiethnic empire.

Read essays about the visual culture of the Qing court

Imperial Workshop and Giuseppe Castiglione, The Qianlong Emperor as Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom: A European artist in China paints a portrait of the emperor.

Read Now >

Portraits of Shi Wenying and Lady Guan: This pair of paintings are ancestor portraits, which are formal, forward-facing portraits of deceased ancestors used for family worship.

Read Now >

Treasure Box of Eternal Spring and Longevity: Skill and interest in carved lacquer reached a new peak during the Qianlong period (1736–95).

Read Now >

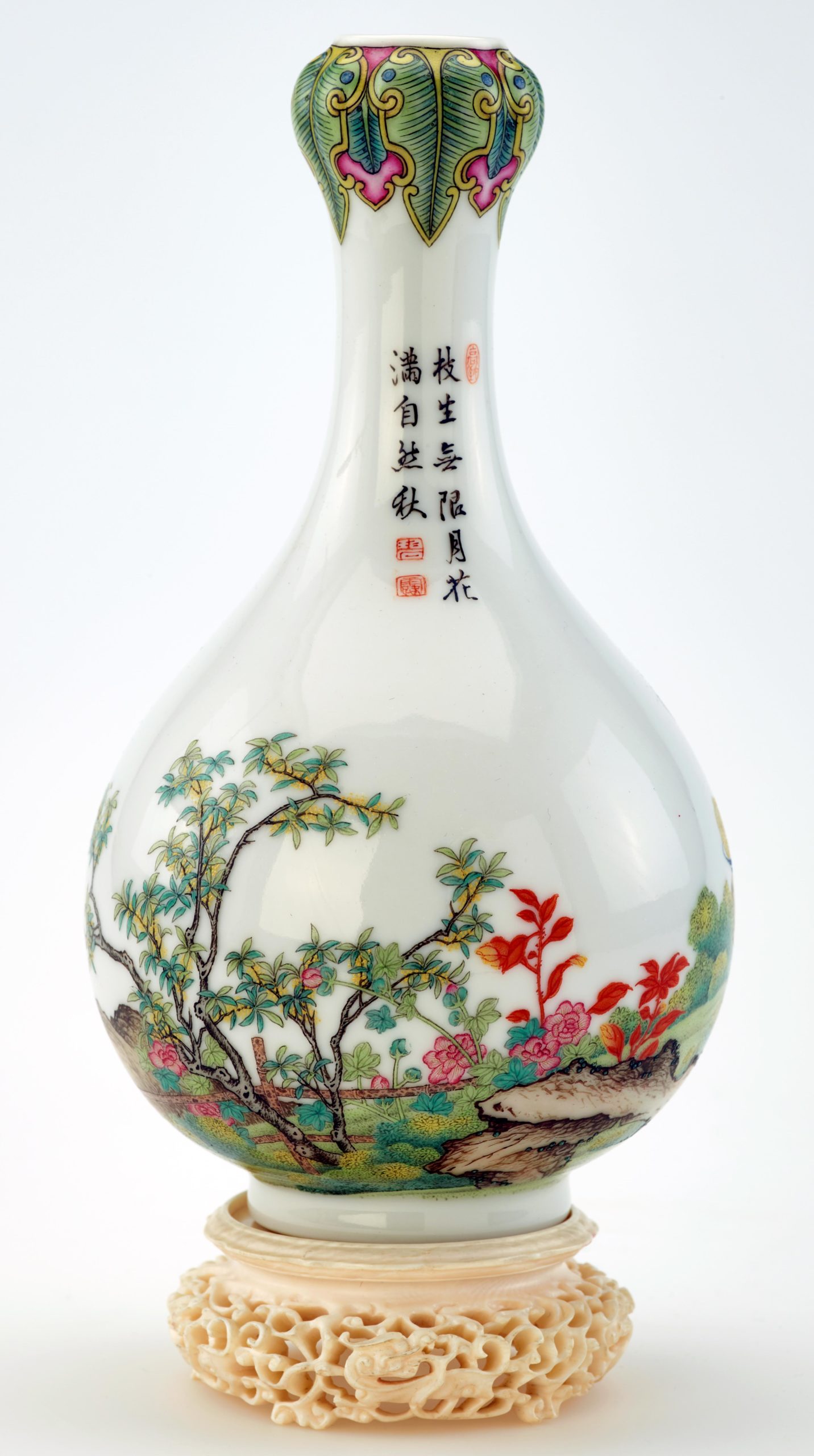

Vase of bottle shape with “garlic” mouth: The fine quality of the porcelain and delicate painting details both suggest that the vase was made for and used by the court.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Architecture

In addition to painting, the Manchus also collaborated with Jesuit missionaries at the court on architectural projects. In the eighteenth century, the Qianlong emperor initiated a massive renovation of the imperial garden site of Yuanmingyuan, or “The Garden of Perfect Brightness,” a vast complex that was modeled after European villas and housed numerous cultural relics. Structures displayed both Chinese and Rococo architectural features, with attention to European illusionistic techniques such as linear perspective, while European-style edifices incorporated elements from Chinese mythology—a hybrid approach that signaled the Manchu fascination with all things exotic. After British and French troops completely looted and torched the site during the Opium Wars (a foreign crisis between China and the West that began in south China over opium smuggling) in the nineteenth century, the ruins became a nationalist symbol to some—and questioned by others, including the contemporary artist Ai Weiwei (as discussed in an essay below)—and the subject of repatriation efforts through the present. By the turn of the twentieth century, the Empress Dowager Cixi had declared war on foreign powers in the Yihetuan Movement of 1900 (also known as the Boxer Rebellion), compromising her international reputation as the Qing dynasty neared its end.

Read essays about architecture

Xunling, The Empress Dowager Cixi with foreign envoys’ wives: This photo was taken in the Hall of Happiness and Longevity (Leshou tang) in the Summer Palace, Beijing.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Arts in Jiangnan

While artistic production hummed along at the Manchu court in eighteenth-century Beijing, artists and patrons outside of the court also cultivated thriving art worlds, such as in the cultural region of the Yangtze River delta known as Jiangnan, or “south of the river.” Yangzhou is one such Jiangnan city that thrived due to its location on the Grand Canal, the main north-south route for the transport of salt (which was mined and shipped all over China) during the Qing dynasty. The Qing court carefully monitored Yangzhou, first as a site of resistance during the initial Manchu siege of the city, and later as a center for scholarship and publishing amid the Qing literary inquisitions. At the same time, the Qing emperors also rewarded the city by making it a repository for scholarship, with one set of the vast imperial encyclopedia stored in Yangzhou, and by designating it as the seat of the salt administration.

A Zisha “Ru Ding” teapot made by Yang Pengnian, with Chen Mansheng mark, Yixing ware, c. late 18th–early 19th century (Shanghai Museum)

As the city grew increasingly wealthy between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, prominent merchants built public memorials and private garden estates, where they often solicited the work of poets and artists. These patrons signaled a shift in Qing society, where many old families (such as those attaining government posts through classical education) slipped from power as merchants profited from the opportunities within the new regime. Although they often lacked the education to partake in the more sophisticated arts and scholarship, these patrons idealized the scholarly lifestyle and so commissioned paintings, gardens, poetry, and tea culture.

Watch videos about art in Jiangnan

/1 Completed

The Shanghai School

As trade shifted from the Grand Canal to the East China Sea during the latter half of the Qing dynasty, the city of Shanghai became a vibrant hub for the arts. The city not only attracted itinerant artists from the Jiangnan region, but also court painters who had previously enjoyed high status for their work under the Qianlong emperor, but who had sunk to the level of palace servants as imperial support waned in the nineteenth century. Art historians often use the term “Shanghai school” to refer to painters active in the city who developed commercially successful styles from various artistic sources. Some created modern calligraphy based on the study of seal and clerical inscriptions engraved on ancient bronze and stone monuments, a practice called “epigraphy.” Others looked to the vivid garden subjects of eighteenth-century Yangzhou for enlivening urban life through painting. Meanwhile, other artists turned away from sophisticated genres (such as landscapes) and media (such as painting and calligraphy) altogether, instead exploring popular subjects through woodblock prints and photography.

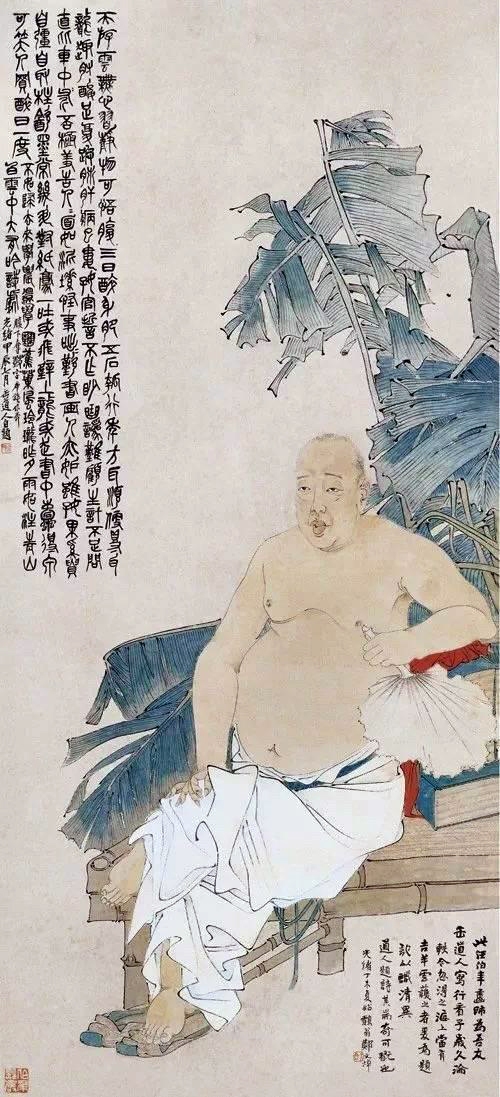

The artist’s confrontational manner can be read as tormented, a representation that fits with what we know about his life and the tragic period in which he lived—civil war amid the rise of Shanghai as a cosmopolitan, international port city. Ren Xiong, Self-Portrait, c. 1850, ink and colors on paper, 177.5 x 78.8 cm (Palace Museum, Beijing)

Although literary and artistic circles offered avenues for patronage and social prestige in nineteenth-century Shanghai, foreign and domestic turmoil challenged many artists. The Opium Wars (a foreign crisis between China and the West that began in south China over opium smuggling) ended in the Treaty of Nanjing, which opened Shanghai as a treaty port. Shanghai quickly transformed into an international commercial city, with residential areas for foreigners (known as the British, French, and American concessions), and soon it became the largest port in Asia. However, around the same time that the British and French sacked Beijing (during the Second Opium War), the Taiping Rebellion broke out in the countryside, and much of the Jiangnan region fell under rebel control.

The Taiping Rebellion was an uprising of Chinese peasants which nearly toppled the dynasty and destroyed the way of life for China’s scholar-gentry class, the literati, especially those living in the Jiangnan region. Tens of millions died and millions more were displaced—and many of these refugees fled to Shanghai, further inflating the population of the city. With the unprecedented challenges of the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion, the end of the Qing dynasty led many artists to re-examine many of the central features of Chinese culture and history.

Read essays about artists associated with the Shanghai School

/2 Completed

The arts of the Qing dynasty reflected the global, multiethnic agenda of its Manchu rulers. Chinese imperial traditions, Buddhism, and European innovations shaped visual cultures at the court, while Han scholarship and garden cultures in Jiangnan responded to the Qing social and economic shifts. As tensions between Qing and foreign powers mounted amid domestic turmoil in the nineteenth century, artists began to ask a modern question: what of the past can serve us in this new world?

Key questions to guide your reading

How did the Manchu court use art to convey power in a multiethnic empire?

How did the arts of Qing China respond to the arts in other world areas, such as Europe?

Which aesthetic traditions did artists engage with in the Jiangnan region?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did the Manchu court use art to convey power in a multiethnic empire?

How did the arts of Qing China respond to the arts in other world areas, such as Europe?

Which aesthetic traditions did artists engage with in the Jiangnan region?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Manchu

Jesuit

Qianlong emperor

Jiangnan region

hybrid

looting, repatriation, nationalism

Grand Canal

Shanghai School

epigraphy

woodblock prints

Opium Wars

Treaty of Nanjing

Taiping Rebellion

Empress Dowager Cixi

Boxer Rebellion

Learn more

For more on auspicious imagery in Chinese history, read an essay about Emperor Huizong’s Auspicious Cranes