Buddhism: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 26

Buddhism in Chinese Art (2nd century through 907 C.E.)

Buddha, Cave 20 at Yungang, Datong, China, c. 460 C.E. (photo: Marcin Białek, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The story of Buddhist art in China is one of dynamic cultural and artistic exchange beginning with the earliest images of the Buddha based on Indian and Central Asian prototypes through its eventual Sinicization for a Chinese audience. This chapter explores Buddhist art in China from the Han through the Tang dynasties, a period that saw the introduction of Buddhism to China and its widespread growth as a major religion. After the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 C.E., we will see how non-Chinese rulers who invaded north China during the Period of Division (220–589 C.E.), and then the later Tang dynasty (618–917 C.E.), used the religion and the construction of Buddhist monuments to assert their authority and legitimacy. Their subjects found in Buddhism a religion that could support their spiritual needs.

Background to Buddhism

To understand early Chinese Buddhist art, we must first travel back in time hundreds of years and across Eurasia to ancient India and the origins of Buddhism. Buddhism was founded by prince Siddhartha Gautama, who became the Historical Buddha (also known as Shakyamuni) after his enlightenment (nirvana).

Early Buddhist art

Early Buddhist art (whether in South Asia, Central Asia, or East Asia), focuses on visual depictions of the Historical Buddha and narratives of his life story and past lives. Early Buddhist art is aniconic, meaning the Buddha is not represented in human form.

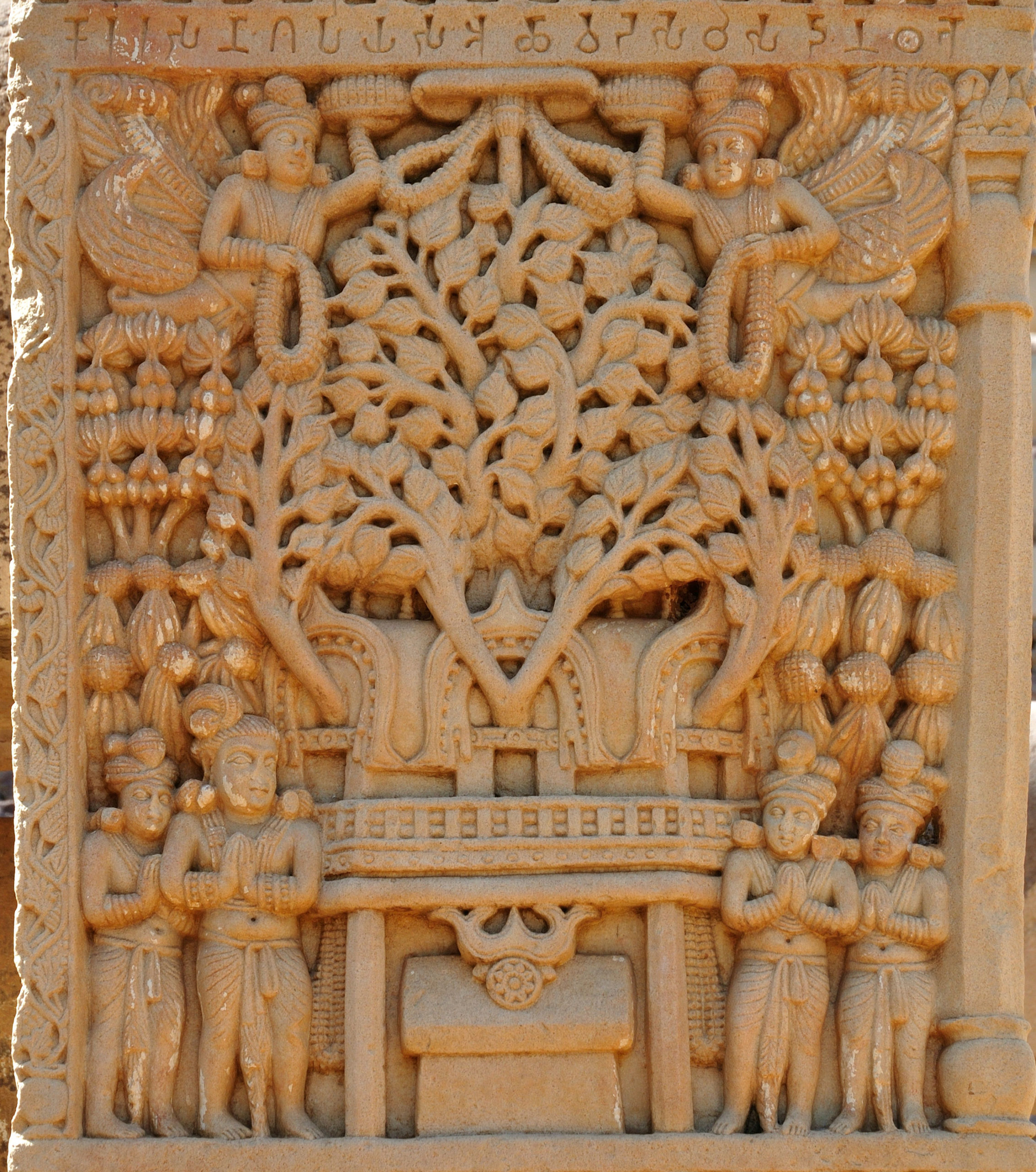

The earliest images of the Buddha appear to avoid depicting him in human form, and sometimes refer to him with forms like a bodhi tree. The fig tree under which the Buddha reached enlightenment became known as the Bodhi (“awakened” or “enlightened”) tree. Bodhi tree with shrine, eastern gateway, Sanchi Stupa no. 1, 2nd–1st century B.C.E., India (photo: Biswarup Ganguly CC BY 3.0)

Instead, Buddha is represented using symbols, such as the Bodhi tree (where he attained enlightenment), a wheel (symbolic of Dharma or the Wheel of Law), and a parasol (symbolic of the Buddha’s royal background), just to name a few. The use of symbols to depict the Buddha may have been inspired by his achievement of parinirvana and release from the cycle of rebirth (samsara) and existence in a physical form upon his death.

The cross-legged Bodhisattva Maitreya is shown here, on the east wall of the antechamber of Cave 9, phase II, after 650, Yungang Grottoes, Datong, China (photo: G41rn8, CC BY-SA 4.0)

As Buddhist art developed over time, the Historical Buddha was eventually depicted in human form. [1] Bodhisattvas, enlightened beings who postpone complete liberation (parinirvana) from the cycle of rebirth (samsara) to help others achieve enlightenment, were also incorporated into the vocabulary of Buddhist art. The bodhisattvas that appear most frequently in Buddhist art are often introduced by their Sanskrit names. In Chinese art, the bodhisattvas Avalokitesvara (Guānyīn 觀音 in Chinese) and Maitreya (Mí-lè 彌勒 in Chinese) are among the most frequently represented. Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion, hears the cries of the suffering, while Mi-le offers hope for the future in times of despair.

Read essays about images of the Buddha and bodhisattvas

/3 Completed

Early Chinese Buddhist Art

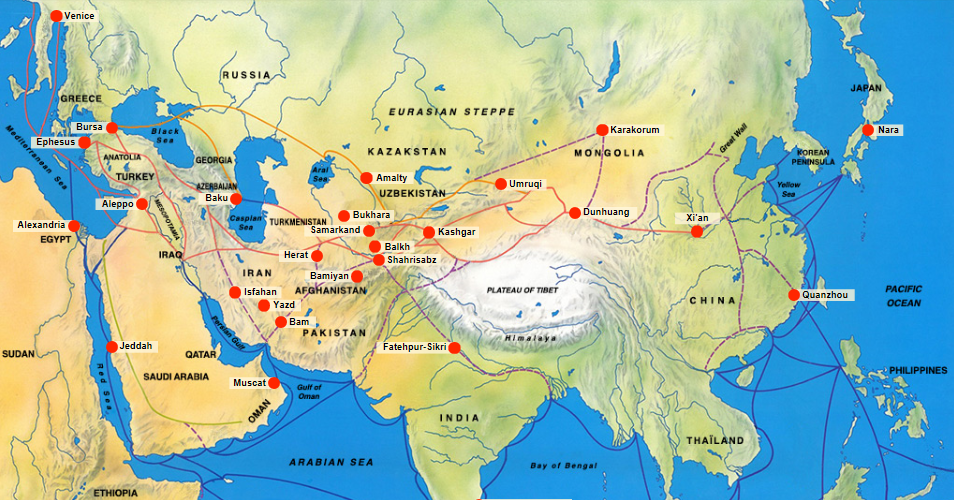

Map of the Silk Roads (various overland routes across Eurasia)

Buddhism first arrived in China during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.). The earliest visual images of the Buddha to arrive in China were likely drawings and small portable images from India and Central Asia transmitted by travelers along the ancient Silk Roads. As early as the second century, local artisans in China produced their own images and sculptures of the Buddha using foreign models.

Left: Seated Buddha, Mahao Cliff Tomb, Sichuan Province, Eastern Han Dynasty, late 2nd century C.E. (photo: Gary Todd, CC0); right: Seated Buddha from Gandhara, c. 2nd–3rd century C.E., Gandhara, schist (© Trustees of the British Museum)

One of the earliest images is a carving of a seated Buddha wearing a Gandharan-style robe discovered in a tomb dated to the late 2nd century C.E. (Eastern Han) in Sichuan province. [2] Ancient Gandhara (located in present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India) was a major center for the production of Buddhist sculpture under Kushan patronage. The Kushans occupied portions of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north India from the 1st through the 3rd centuries and were the first to depict the Buddha in human form. Gandharan sculpture combined local Greco-Roman styles with Indian and steppe influences. Compare the Chinese tomb carving of Buddha with the sculpture of a seated Buddha from Gandhara above, and note the similarity in the way the robe falls across the body in both images.

Rock-cut Cave Temples and Colossal Buddhas

After the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 C.E., China went through a period of upheaval before being reunited again by the Sui dynasty in 581 C.E. Although this period, known as the Period of Division, is marked by instability and the rise and fall of over two dozen dynasties and smaller kingdoms, arts and culture flourished. In part, this was due to the arrival of non-Chinese nomadic invaders and tribal groups, who successively conquered portions of north China throughout this period. One clan, the non-Chinese Tuoba, united the north in 439 C.E. and adopted Buddhism as the state religion. Buddhism grew in popularity under the rule of northern dynasties ruled by non-Chinese families, giving rise to new artistic forms and styles based on foreign models. Over time, as Buddhist art developed in China, these foreign models were eventually Sinicized to legitimize the rule of non-Chinese nomadic rulers.

Read about the Period of Division (220–589 C.E.)

/1 Completed

Map with locations of important rock-cut cave temples and colossal Buddhas in China (underlying map © Google)

Rock-cut cave temples

During the Period of Division, rock cut cave temples were constructed at Yungang, Longmen, Dunhuang, and Xiangtangshan. These cave temples, which were modeled after earlier cave temples in South Asia (such as at Ajanta), feature thousands of images. The sculptures and paintings found within these caves help us understand the history of the development of Buddhist art in China. Construction at these cave temple sites began during the Period of Division and continued during the Tang dynasty, a period of peace and prosperity when China was once again unified under Han Chinese imperial rule.

Caves and niches of Yungang, Datong in Shanxi province, China, begun c. 460 C.E. (photo: G41rn8, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Yungang Caves

The Yungang grottoes are among the earliest rock-cut cave temples in China. They were carved under the patronage of Northern Wei rulers in the mid-5th century.

Buddha inside Cave 18, Yungang, Datong, China, c. 460 C.E. (photo: Zhangzhugang, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Buddhist imagery carved into the earliest caves (Caves 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20), which each feature a colossal Buddha, shows a confluence of artistic traditions from South, Central, and East Asia. However, in the late 5th century, Sinicization reforms under Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei influenced the introduction of a new Chinese style of Buddhist art. This style is often referred to as the mature Northern Wei style, a Sinicized style of Buddhist art that moved away from traditional Indian and Central Asian styles. Sinicization reforms were used to legitimize the rule of non-Chinese rulers of the Northern Wei over a Chinese imperial dynasty.

Entrance to Central Binyang Cave, 508–523 C.E. Longmen Caves, Luoyang, China (photo: A1AA1A, CC0 1.0)

Longmen Caves

The construction of rock-cut caves at Longmen also began during the Northern Wei dynasty, after the move of the capital to nearby Luoyang in Henan province in 494 C.E. Northern Wei rulers completed one cave temple at Longmen, the Central Binyang Cave. Carved in the early 6th century, the Central Binyang Cave was executed in the mature Northern Wei style.

Vairocana Buddha, monks and bodhisattvas, 673–75 C.E., Tang dynasty, limestone, Luoyang, Henan province (Larry F. Ball, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Construction at the Longmen caves continued under Tang imperial patronage with the carving of the Fengxian and Kanxing cave temples. Like the colossal images of the Buddha in the early caves at Yungang, the Fengxian cave shrine features a monumental Buddha. However, instead of the Historical Buddha, the Fengxian cave features Vairocana Buddha on a dramatic stage-like setting flanked by colossal images of jeweled bodhisattvas, robed monks, heavenly kings, and thunderbolt bearers (vajrapani). Vairocana Buddha, the Cosmic Buddha of the Flower Garland (Avatamsaka) Sutra, presides over infinite worlds, transcending time and space. The cave imagery was sponsored by Emperor Gaozong and his wife Empress Wu Zetian, who were patrons of the teachings of the Flower Garland Sutra. Similar to Northern Wei Buddhist cave monuments, the Fengxian cave imagery can be seen as a statement of imperial authority. In this case, Tang imperial rule is likened to that of the Cosmic Buddha Vairocana. [3]

Mogao Caves at Dunhuang

The Mogao, or “Peerless” caves, located near Dunhuang (an ancient oasis town along the Silk Roads), in Gansu province, were first carved in the late 4th century by a pair of wandering monks. The monks carved small niches for solitary meditation into a two-kilometer-long cliff located along the Daquan River in the middle of the desert.

The central pillar in Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou dynasty, 557–581 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

This site would eventually become one of the most important centers for Buddhism in the world. From the 6th through the 14th centuries, over a thousand caves of various sizes were carved from the east facing cliff, many of which were decorated with paintings and sculptures, giving the site the nickname “Caves of the Thousand Buddhas.”

The complete Prince Mahasattva jataka tale mural, Mogao Cave 428, Northern Zhou, 557–81 C.E., Dunhuang (image courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy)

Many early caves at Mogao are painted with jataka tales (stories of the Historical Buddha’s previous incarnations). These stories convey a moral lesson with a central theme of self-sacrifice for the benefit of others. The tale of Prince Mahasattva, who sacrificed himself to save a hungry tigress and her cubs, is painted on the walls of Mogao Cave 428. Imagine entering the interior of a cave by candlelight and reading the Prince Mahasattva jataka narrative and other stories of the Historical Buddha’s previous incarnations by shining a flickering light toward the wall. How are the jataka narratives in Cave 428 arranged compositionally for this type of viewing experience?

Along with jataka tales, historical narrative paintings are also ubiquitous in the Mogao Caves. The paintings on the walls of Mogao Cave 323, dated to the 7th century during the Tang dynasty, detail stories of the origins of Buddhism in China, as well as early encounters with the religion in China. One narrative focuses on the Han dynasty Emperor Wu and the legend of two metal statues he worshiped that turned out to be early images of the Buddha.

Read essays about the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang

/3 Completed

Cave 17: The Library Cave at Mogao

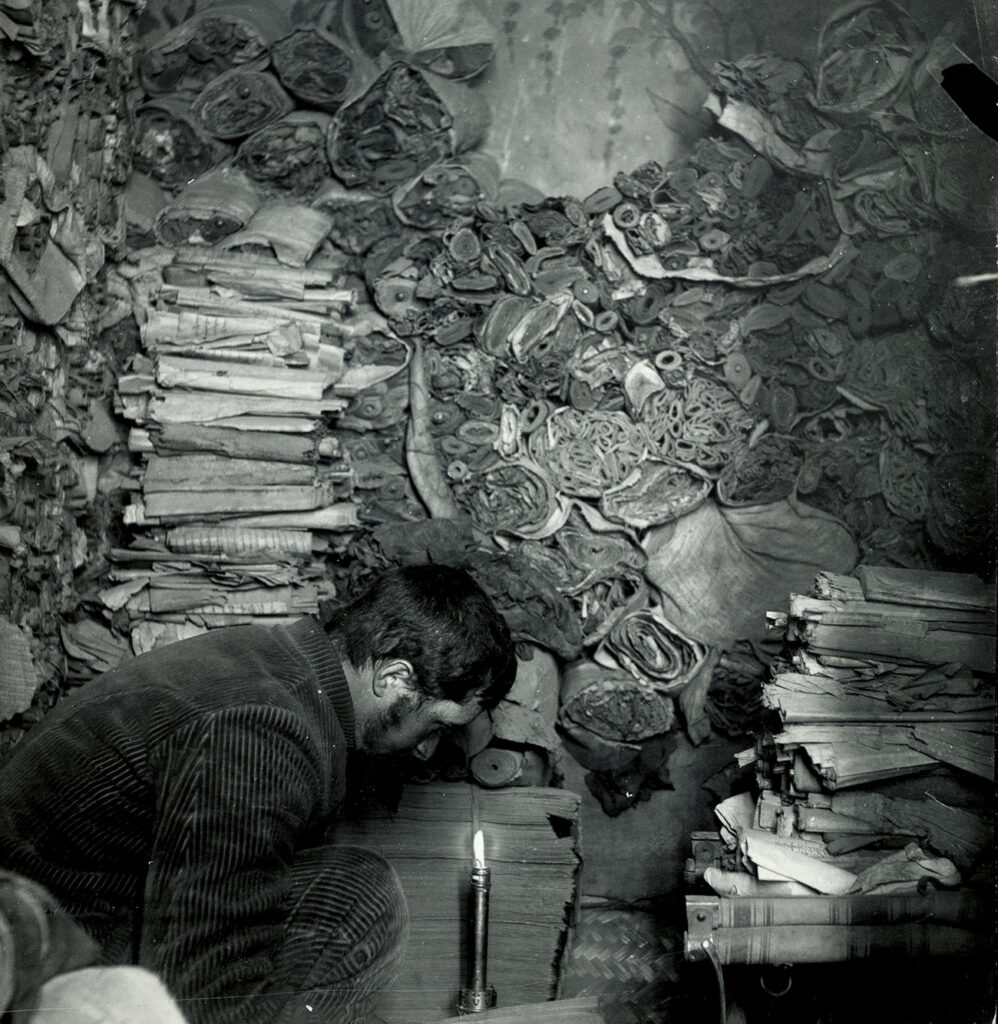

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the Silk Roads were abandoned, and the Mogao Caves were all but forgotten. However, in 1900, a Chinese Daoist monk named Wang Yuanlu, self-appointed guardian of the caves, made an astounding discovery: a hidden cave filled, from floor to ceiling, with tens of thousands of ancient manuscripts, along with silk paintings and other historical artifacts which deeply enrich our knowledge of Buddhism and Buddhist cultures of the past.

Mogao Caves 16–17 (Library Cave), Dunhuang, Gansu Province, China, 862 C.E.; sealed around 1000 C.E. (photo courtesy of Dunhuang Academy)

Cave 17, called the “Library Cave,” due to its abundant collection of manuscripts, was hidden within Cave 16 and sealed in the 11th century. Wang Yuanlu guarded the cave until the British archaeologist and explorer Marc Aurel Stein arrived and convinced him to sell a portion of the contents. Shortly after, Wang sold more manuscripts to the French Sinologist Paul Pelliot. Wang’s sale of precious manuscripts and paintings from the cave is still highly controversial, but he did so to help fund his dream of restoring the Mogao Caves. Today, for better or worse, the contents of the Library Cave are scattered across museum collections in Eurasia.

Remounted fragments (not in correct order) of the Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images, 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (The British Museum)

The distribution of artifacts from the Library Cave across museum collections makes the study of these important materials challenging. For example, fragments of one silk painting collected from Cave 17 by Marc Aurel Stein and dated to the Tang dynasty were eventually divided between two separate museum collections, the British Museum in London and the National Museum of India in New Delhi, complicating its reconstruction and interpretation.

Read two essays about Cave 17 at Mogao

/2 Completed

Xiangtangshan Caves

The earliest caves at Xiangtangshan (“Mountain of Echoing Halls”) were carved during the Northern Qi dynasty (550–577) under the patronage of the royal family and officials. The caves, which number around thirty, are badly damaged due to centuries of human activity (including looting), erosion, and natural disasters. However, like the materials from the Library Cave at Mogao, limestone sculptures and fragments of relief carvings from the Xiangtangshan caves are distributed in museum and private collections around the world.

For example, a limestone relief in the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, D.C., reveals the growth in popularity of Pure Land Buddhism during the 6th century and is one of the earliest extant depictions of the Western Paradise, a heavenly palace setting practitioners believed they could be reborn into.

Read about a relief from a Xiangtangshan Cave

A relief of the Western Paradise of the Buddha Amitabha: An early depiction originally in a cave at Xiangtangshan.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Giant Buddha, 8th century, Leshan, China, 71 m high (photo: fannyss, CC0)

Leshan

Far away from Buddhist centers in the north, the largest colossal image of the Buddha in the world was carved out of a hillside in the 8th century, not too far from Mahao cliff tomb in Sichuan province where one of the earliest images of the Buddha was discovered (discussed above). Deemed the Giant Buddha of Leshan, the 71-meter-high seated Buddha looks out across the Min and Dadu Rivers towards Mount Emei. In contrast to the colossal Buddhas represented in the caves at Yungang and Longmen, the Giant Buddha of Leshan was not constructed to communicate the authority and legitimacy of a ruling family. Instead, the carving of the Buddha was sponsored by a Buddhist monk to oversee and protect ships passing by on the rivers below.

Watch a video about the Giant Buddha

/1 Completed

Buddhism and the Afterlife

After his death, the Historical Buddha was cremated, and many practitioners of the faith chose to follow this practice. However, when Buddhism arrived in China there was already a centuries-long tradition of burying the dead in elaborate tombs with grave goods to create a comfortable and happy afterlife for the soul. Practitioners of the Buddhist faith in China who desired a traditional burial found ways to merge their faith in Buddhism with their views of the afterlife.

For example, a stone slab from a funerary couch, which likely belonged to a noble living in north China during the Period of Division, is adorned with images of Buddhist deities combined with secular imagery of Central Asian entertainers. The use of Central Asian motifs reflects the vibrant cultural exchange between China and Central Asia during this period, while the combination of secular and religious imagery displays a convergence of cultural traditions and belief systems.

Another funerary object that shows the confluence of cultures and faiths during the Period of Division is a stone sarcophagus from the tomb of a Sogdian couple who traveled from Central Asia to Xi’an, China in the 6th century. The sarcophagus is in the shape of a Chinese shrine and is covered with carved surface decoration. The surface decoration gives us a rare glimpse into the life of a foreign couple living in China at the time. It details their lives from birth and marriage to death and the afterlife using narrative imagery. The sarcophagus also highlights the impact of Buddhist art during this period. As Jin Xu demonstrates in his essay on the Wirkak sarcophagus, the narrative illustrations of the Sogdian couple’s life are modeled on carvings and paintings of the life of the Historical Buddha, such as those seen in the rock-cut cave monasteries discussed above.

Read essays about Buddhism and the afterlife

Base of a funerary couch: a combination of images of Buddhist deities combined with secular imagery of Central Asian entertainers.

Read Now >

The Wirkak (Shi Jun) Sarcophagus: An object that shows the confluence of cultures and faiths during the Period of Division.

Read Now >/2 Completed

As we have seen in this chapter, although there was a spark of Buddhist activity in China during the Han dynasty, the arrival of foreign nomadic groups in north China during the Period of Division and their subsequent embrace of Buddhism had a profound and lasting impact on Chinese art. After reunification under the Sui and the Tang dynasties, Han Chinese rulers continued to build upon the traditions established during the previous periods, embracing Buddhism and its multiculturalism.

Notes:

[1] The Kushans, who ruled over portions of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India during the 1st through 3rd centuries, were the first to depict the Buddha in human form.

[2] A small gold-plated bronze statue recently excavated from a tomb of a Chinese official dated to the late 2nd, early third century in Xianyang, Shaanxi province also follows a Gandharan prototype.The statue was excavated in 2021 from Tomb 3015 at Chengren, Xianyang, Shaanxi Province. The tomb contained two statues considered to be among the earliest images of the Buddha discovered so far in China. An announcement of the discovery in English can be found at: Alex Greenberger, “Earliest Gold-Plated Bronze Buddha Statues Found in China’s Shaanxi Province,” ARTnews.com, December 14, 2021.

[3] See Robert L. Thorp and Richard Ellis Vinograd, Chinese Art & Culture (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001), pp. 201–203.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did Buddhist artistic styles develop from the 2nd century through the early 10th century?

How did the construction of Buddhist monuments help legitimize the power and authority of rulers in China?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did Buddhist artistic styles develop from the 2nd century through the early 10th century?

How did the construction of Buddhist monuments help legitimize the power and authority of rulers in China?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Aniconic

Buddhism

Buddha

Bodhisattva

Jataka tales

Period of Division

Pure Land Buddhism

Rock-cut cave temple

Silk Roads

Sinicization

Sogdians

Vairocana Buddha