The origins of Byzantine architecture: an overview

Read Now >Chapter 24

Building new Romes: The Eastern Romans, Umayyads, and Carolingians

Tremissis of Emperor Justinian I, minted in Rome, 527–65, gold, 1.49 gm (photo: The British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The British Museum preserves a gold coin that is unmistakably Roman. The portrait of an emperor in profile appears on one side and a winged goddess or personification of victory appears on the other. Inscriptions identify the emperor as “Our Lord, Justinian, eternal Augustus,” and the place where the coin was minted as Rome. But Justinian reigned as emperor from 527–565, long after Constantinople became the new capital of the empire and the Romans had embraced Christianity (as a small cross on the orb carried by the winged victory suggests). So this coin challenges us to consider what we mean by the term “Roman.” It illustrates the continuity between ancient Rome and the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire that endured through the “middle ages,” a period which also saw the rise of the Umayyads and Carolingians who sought to appropriate the Roman legacy through their art and architecture.

This chapter explores the ways the Eastern Romans, Umayyads, and Carolingians deployed art and architecture from the third–ninth centuries C.E. to construct Roman identities following the rise of Christianity and Islam.

Map with Rome and Constantinople (underlying map © Google)

Christianity and Rome

Baptistery reconstruction, house church, Dura-Europos (Yale University Art Gallery)

When the Romans crucified a Jewish teacher named Jesus in Jerusalem in the first century C.E., his followers claimed he rose from the dead, and they began spreading his teachings throughout the Roman Empire. This new religion became known as Christianity and its adherents Christians. Christianity existed as an illegal religion on the periphery of Roman society until the fourth century, when Christianity was legalized by the Edict of Milan in 313 during the reign of emperor Constantine and eventually became the official religion of the Roman state in 380.

Detail of the Cubiculum of the Veiled Woman, Catacomb of Priscilla, late 2nd–4th century C.E., Rome, Italy

The earliest surviving Christian art dates from the third century C.E. A Christian house church and Jewish synagogue stood near each other on the edge of the city of Dura-Europos (Syria) on the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire. Both were converted from houses for religious use: the synagogue in the second century and the Christian house church in the first half of the third century. Both church and synagogue displayed wall paintings with biblical figures and scenes that reflect the beliefs of their communities.

Christ as the Good Shepherd (Early Christian), c. 300–50 C.E., or possibly an early 3rd-century Roman garden sculpture, marble, 39 inches high (Museo Pio Cristiano, Vaticano, Rome). Right hand, arms sections, and everything below the bottom of the skirt has been restored.

Other early Christian artworks survive in underground burials known as “catacombs” in Rome. Christians decorated the catacombs with carvings and paintings displaying nascent images of belief and salvation, such as believers with hands raised in prayer, stories from the Hebrew Bible and Christian New Testament, and Christ as the Good Shepherd. Carved images of the Good Shepherd appear on sarcophagi and in other sculptures as well, as seen in a marble sculpture at the Vatican. This motif, which was common in the first centuries of Christian art, was adapted from pre-Christian, pagan art to illustrate the teachings of Jesus, who said: “I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep” (John 10:11). In this transitional period, it is often difficult to say for certain which images of shepherds represent Christ.

View down the nave towards the apse, Basilica of Santa Sabina, 422–32 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Following the legalization of Christianity in 313 and support from emperors such as Constantine, Christian art and architecture quickly became increasingly public and monumental. Christians adopted the form of the Roman basilica—a hall-like structure that predated Christianity and was not originally used for religious purposes—to build churches in which growing numbers of Christian converts could gather (as seen with the fifth-century basilica of Santa Sabina in Rome). Constantine also built martyria, such as Saint Peter’s basilica in Rome and the church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, which marked the burials of martyrs like Saint Peter and the sites of sacred events like Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection.

Watch videos and read essays about early Christianity and Rome

The Good Shepherd in Early Christianity: Find out why figures like Hermes were recast as the Good Shepherd in early Christianity.

Read Now >

Early Byzantine architecture after Constantine: Basilicas and new architectural forms appeared following the reign of emperor Constantine.

Read Now >

Basilica of Santa Sabina, Rome: This impressive church borrowed its plan and its columns from ancient pagan buildings.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Constantinople: New Rome

The Colossus of Constantine, c. 312–15 (Palazzo dei Conservatori, Musei Capitolini, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Between 324–330 C.E., Constantine built a new Roman capital at the ancient city of Byzantium on the Bosporus strait, which was renamed “New Rome” and “Constantinople,” and is today known as Istanbul. Constantinople now became the center of the Roman Empire.

The Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, approximate boundaries, mid-6th century (underlying map © Google)

Modern historians have often described the Roman state now centered in Constantinople as the “Byzantine Empire” and the period that followed as the Early Byzantine period. But the term “Byzantine Empire” is misleading and many scholars are now abandoning it. Their new capital and Christian religion notwithstanding, the “Byzantines” still understood themselves as Romans and referred to their homeland as Romanía (“Romanland”) in both Greek and Latin sources, and the Roman state and culture continued to thrive from its new capital of Constantinople. So, it is more accurate to refer to the “Byzantine” state as the Eastern Roman Empire, as I do in this essay. [1]

The boundaries of the Eastern Roman Empire expanded to their greatest extent during the reign of emperor Justinian and empress Theodora in the sixth century, but this period also saw civil unrest. The Nika riots of 532 destroyed Constantinople’s main church, which was dedicated to Christ as Hagia Sophia (“Holy Wisdom”), but which was also simply referred to as the “Great Church.” After brutally suppressing the revolt, Justinian seized on the opportunity to rebuild Constantinople’s cathedral in an innovative new form.

Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532–37 (photo: © Robert G. Ousterhout)

Designed by Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles, both of whom were mathematicians and engineers as well as architects, Justinian’s new Hagia Sophia was a towering basilica with a soaring, central dome (a “domed basilica”). Adorned with golden mosaics and imported marbles, Justinian’s new church originally displayed no figural images, and contemporary commentators praised the new structure for its innovative architecture and rich materials.

Read essays and watch videos about Constantinople

Innovative architecture in the age of Justinian: Dramatic new developments occurred in Byzantine architecture.

Read Now >

Hagia Sophia, Istanbul: The golden dome of this vast building appears suspended from heaven.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Belief and ideology in Ravenna

Apse detail, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC: BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As the center of the Roman Empire shifted to the east in the fourth century, the city of Rome and the Italian peninsula became increasingly vulnerable to invasions by Germanic peoples from the north (such as the Ostrogoths).

Ostrogothic Kingdom and Eastern Roman Empire, c. 525 (underlaying map © Google)

Ravenna, a city surrounded by swamps in northeast Italy, served as a more defensible western capital in the fifth and sixth centuries. But despite its defensive advantages, the Ostrogothic king Theodoric still captured Ravenna in 493 and made it the capital of his Ostrogothic Kingdom until the Eastern Romans recaptured the city in 540 during the reign of Justinian.

Theodora mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Several churches and baptisteries still preserve mosaics from the periods of Byzantine and Ostrogothic rule, including the iconic images of emperor Justinian and empress Theodora in the church of San Vitale, which illustrate religious beliefs and political ideologies of the period in vivid color.

Watch videos and read an essay about art in Ravenna

Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna: Mosaics in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, and the conflict between the Ostrogoths and the Byzantines.

Read Now >

San Vitale and the Justinian Mosaic: One of the most important surviving examples of Byzantine architecture and mosaic work.

Read Now >

Empress Theodora, rhetoric, and Byzantine primary sources: Byzantine texts praise and slander the empress Theodora, who appears in this famous mosaic in Ravenna.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Cross-cultural exchange and the rise of the Umayyads

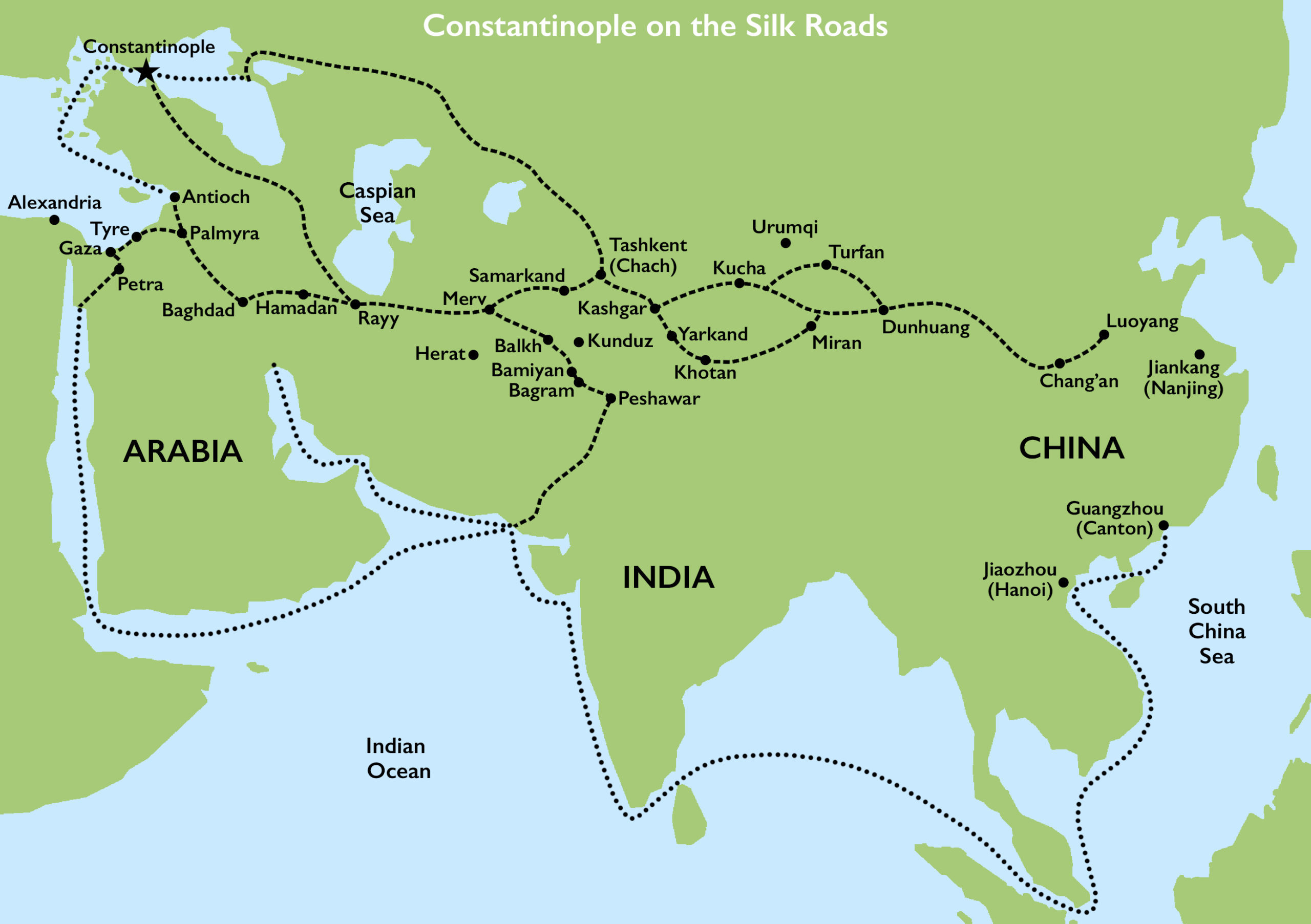

Map showing Constantinople (upper left corner) in the network of trade routes that made up the Silk Roads, adapted from Françoise Demange, Glass, Gilding, and Grand Design: Art of Sasanian Iran (224–642) (New York: Asia Society, 2007) (Evan Freeman, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Situated at the western end of the Silk Road, Constantinople was a hub of cross-cultural exchange, which is reflected in the art of the period. Silks, like those worn by the figures in the Theodora mosaic at San Vitale in Ravenna, were imported from as far as China and became synonymous with the wealth and power in the court of Constantinople.

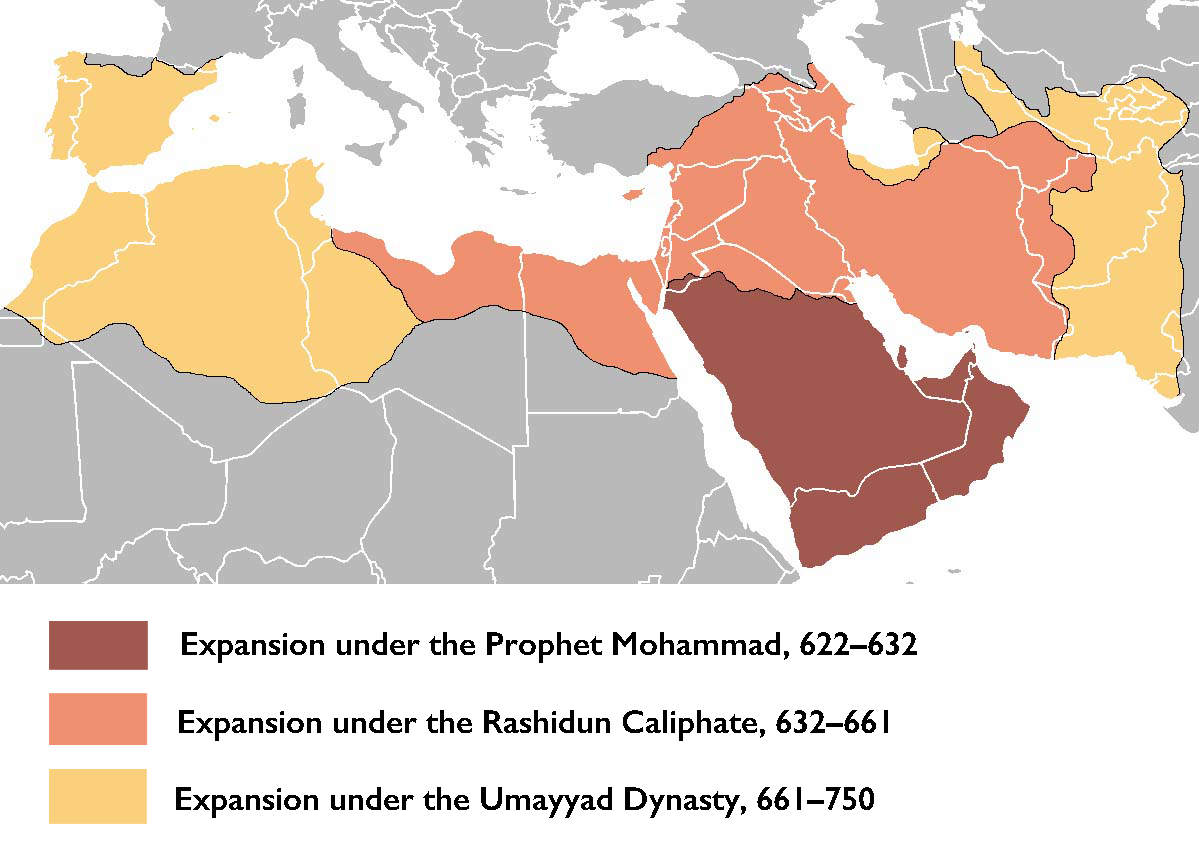

Map indicating the phases of expansion under the Prophet Mohammad, the Rashidun caliphate, and the Umayyad Dynasty

The early seventh century saw the ascent of Muhammad—a merchant-turned-religious leader from Mecca (now in Saudi Arabia)—who amassed followers and gained control of the Arabian Peninsula before his death in 632. Muhammad’s teachings became known as Islam and his followers as Muslims. Muhammad was succeeded by four caliphs (the Rashidun Caliphate) who ruled from 632–661, and later by the Umayyad Caliphate, which established the ancient city of Damascus (Syria) as its capital in 661.

View of the the prayer hall from the courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus (treasury at right), Syria (photo: Erik Shin, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Muhammad’s successors conquered vast swaths of West Asia, North Africa, and the Iberian Peninsula, much of which had been part of the Eastern Roman Empire. Artisans working in these formerly Roman territories continued to practice their crafts under their new Arab rulers, who now became heirs to Roman artistic and architectural traditions.

Prayer hall, Great Mosque of Damascus (photo: Seier+Seier, CC BY 2.0)

In Damascus, where an ancient temple to Jupiter and a Christian church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist once stood, the Umayyad caliph al-Walid II now built a new mosque between 708 and 715 C.E. The Great Mosque of Damascus appropriated the form of a basilica and displayed Byzantine-style mosaics depicting vegetation, landscapes, and architecture, which must have looked familiar to the Christian population of the city, but which lacked the figural images and Christian motifs commonly found in Byzantine churches like San Vitale.

Read essays about cross-cultural exchange and the rise of the Umayyads

Cross-cultural artistic interaction in the Early Byzantine period: Global networks are not just a modern phenomenon.

Read Now >

The Great Mosque of Damascus: On the site of a Roman temple and Christian church, the Great Mosque of Damascus now stands as one of the world’s most important historic structures.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Icons and Empires

Approximate boundaries of the Byzantine Empire in the mid-eighth century (underlying map © Google)

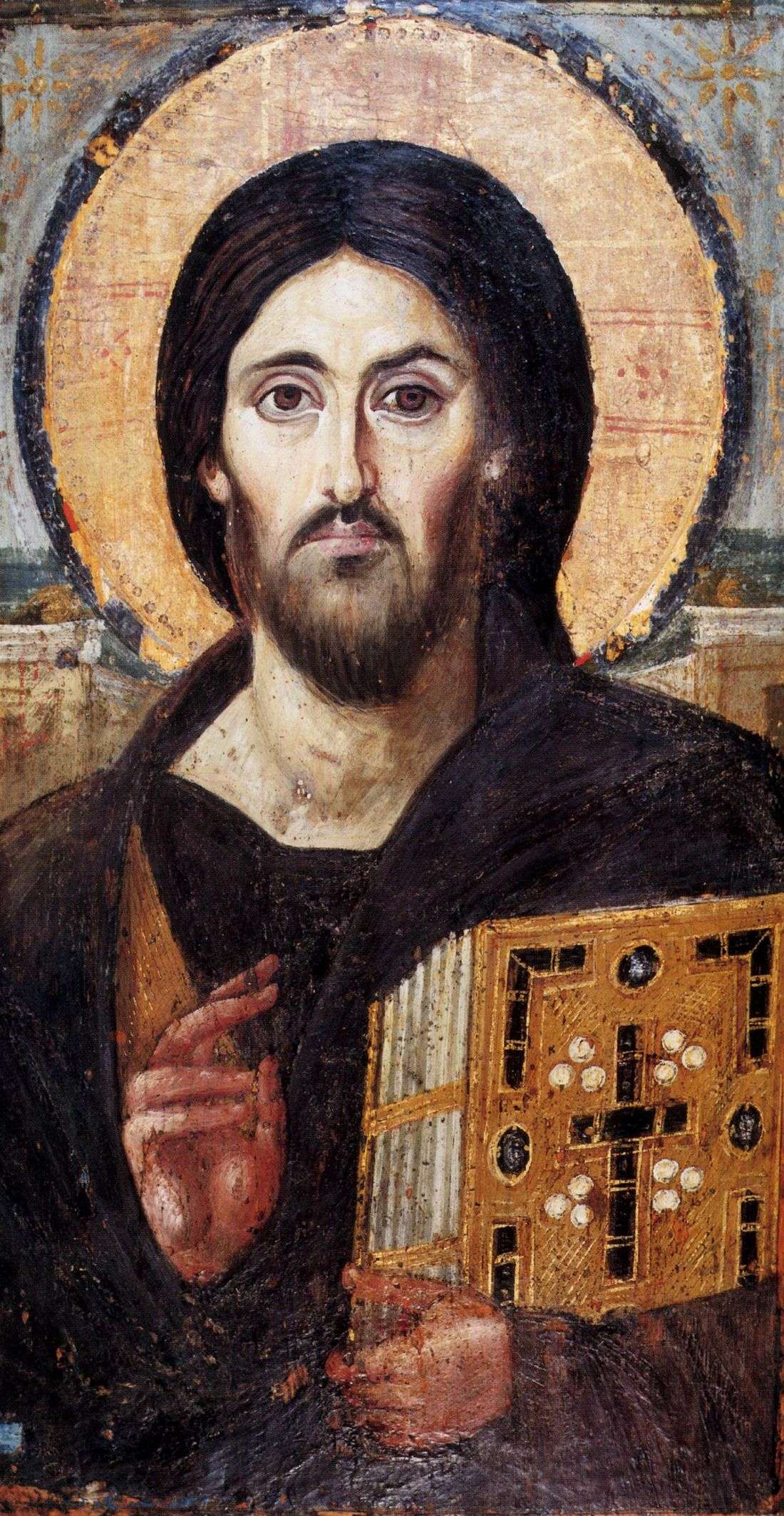

The significant loss of territories to the Arab invaders threw the Eastern Roman Empire into turmoil—which some likely interpreted as a sign of God’s displeasure—and a new controversy over religious images, or “icons,” erupted in Constantinople in the 700s. The Iconoclastic Controversy concerned artistic representations of Christ and the saints, championed by the pro-image “iconophiles” but opposed by the anti-image “iconoclasts.”

Icon with Christ Blessing, first half of the 6th century, encaustic on panel, 84 x 45.5 x 1.2 cm (The Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai, Egypt)

As the Iconoclastic Controversy unfolded in the Eastern Roman capital, what is today France and Germany saw the ascent of Charlemagne and his Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne came into conflict with the Eastern Romans in Italy and criticized their use of icons. Attempts at diplomacy between the Eastern Romans and the Carolingians failed. The Carolingians questioned the rule of the Eastern Roman empress Irene on the basis that she was a woman, and in 800 Charlemagne was crowned as “Emperor of the Romans” by pope Leo III in Rome (Charlemagne’s empire would later become known as the “Holy Roman Empire”).

Palatine Chapel, consecrated 805, Aachen, Germany (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Charlemagne sought to appropriate the Roman legacy in direct competition with the Eastern Romans who ruled from Constantinople. His octagonal Palatine Chapel in Aachen (Germany) echoed the form of the church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem (believed to mark the site of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection), the octagonal San Vitale in Ravenna, and may also have been modeled on the Chrysotriklinos throne room and reception hall in the imperial palace in Constantinople (now destroyed).

Read essays about icons and empires

Byzantine Iconoclasm and the Triumph of Orthodoxy: Learn why the Eastern Romans argued about images for over a century.

Read Now >

Byzantine architecture during Iconoclasm: Learn how territorial losses and the Iconoclastic Controversy impacted Eastern Roman architecture.

Read Now >

Palatine Chapel, Aachen: The octagonal plan references earlier churches and the Great Palace in Constantinople.

Read Now >/4 Completed

The long history of the Christian Eastern Roman Empire would endure until Constantinople fell to the Muslim Ottomans in 1453. In the intervening centuries, many would seek to appropriate the legacy of Rome by associating themselves with the Eastern Romans of Constantinople, including Kyivan Rus’, Norman Sicily, and Venice. Even after conquering Constantinople in the fifteenth century, the Ottoman sultan Mehmet II adopted the title of Kayser-i Rûm (“Caesar of the Romans”), and Moscow—the emergent capital of Russia—styled itself as the “Third Rome,” showing that the legacies of Old Rome and New Rome remained as potent as ever.

Notes:

[1] Anthony Kaldellis has also argued that the Eastern Roman state is more accurately described as a “monarchical republic” than an “empire.” Anthony Kaldellis, The Byzantine Republic: People and Power in New Rome (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015); Anthony Kaldellis, Romanland: Ethnicity and Empire in Byzantium (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2019).

Key questions to guide your reading

How was the legacy of ancient Rome impacted and appropriated by Christianity and Islam?

What roles did emperors, empresses, and other patrons play in the production of art and architecture during this period (c. third–ninth centuries)?

What roles did art play in the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire and why were these challenged in the eighth and ninth centuries?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow was the legacy of ancient Rome impacted and appropriated by Christianity and Islam?

What roles did emperors, empresses, and other patrons play in the production of art and architecture during this period (c. third–ninth centuries)?

What roles did art play in the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire and why were these challenged in the eighth and ninth centuries?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

house church

synagogue

catacomb

martyrium (plural: martyria)

dome

domed basilica

mosaic

cross-cultural exchange

Silk Road

caliph

Learn more

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

About the chronological periods of the Byzantine Empire

The lives of Christ and the Virgin in Byzantine Art

Ancient and Byzantine Mosaic Materials

Mosaics in the early Islamic world

Paintings in the early Islamic world

The rise and fall of the Byzantine Empire – Leonora Neville – Ted Talk

Anthony Kaldellis, Byzantium Unbound (Leeds: Arc Humanities Press, 2019)