Introduction to Andean Cultures: Sophisticated textile weaving, ceramics, and metallurgy are but some of the amazing accomplishments of Andean cultures.

Read Now >Chapter 11

Early South America (c. 3000 B.C.E.–2nd century C.E.)

Introduction

The way people interact with their environment can be an important influence on how cultures develop and change over time. Things that are unpredictable, like weather, and things that are constant and dependable, like geological features, can both contribute to how people understand the world they live in. The people of ancient South America had different cultural responses to their environment based on where they lived within a diverse topography.

This chapter is the first of three that focus on ancient South America. They are split into Early, Middle, and Late time periods. This is not, however, how scholars have divided up the history of the area (they use six divisions, and there is constant debate about the usefulness of those!). The streamlined organization found here groups more cultures together so that the general trends within time frames are easier to understand.

Map of South America with the Andes Mountains indicated

You will notice that these three chapters focus on the Andean region, predominantly the area that is now the modern countries of Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. This is due to the history of archaeology in the region rather than the relative importance of the area. Civil conflicts in Colombia, for example, meant that there were many decades when archaeology was not possible in many locations, and therefore there is less published information on cultures from that area than for Peru, where there has been well over a century of nearly constant archaeology.

There is also the issue of how different areas preserve archaeological materials. Dry conditions preserve most material better than wet conditions, and so archaeology in the jungle region of the Amazon has been more difficult than the dry desert coast of Peru. Ultimately, however, the greatest threat to our knowledge of ancient cultures is looting and black-market trafficking of ancient objects, which destroys their context and uproots them from the present-day communities who are their descendants.

In the following essay, you will read about how a broad number of ecological zones gave birth to a wide variety of artistic traditions: sophisticated textile weaving, ceramics, and metallurgy, as well as architectural traditions based in adobe on the coast and stone in the highlands.

Essay to read

/1 Completed

The next essay below discusses some of the characteristics shared by most Andean art practices: approaches to medium and technique that produced sophisticated works of art, often meant to denote the high status of elites.

Essay to read

Introduction to Ancient Andean Art: Artists crafted objects of both aesthetic and utilitarian purposes from ceramic, stone, wood, bone, gourds, feathers, and cloth.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Five cultures

Peru and Ecuador with early cultures, sites, and cities indicated (underlying map © Google)

This chapter will look at five early cultures of the ancient western coast of South America: Caral, Chavín, Cupisnique, Paracas, and Salinar. It is divided into topics—cities and sacred spaces, adorning the body, and early ceramics—that allows us to think about specific ways these cultures chose to express themselves and their relationship to the world.

Archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar (photo: Sharon odb, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cupisnique and Chavín were highly influential cultures, but the area over which they seemed to have had actual control was small. Salinar and Caral are lesser-studied, and right now Caral is just one archaeological site rather than a broad cultural area. Paracas, on the other hand, was a culture that occupied a fairly large area over a long period of time, and they have been studied extensively, so we have enough archaeological information to be able to give a detailed overview for them.

One introductory essay

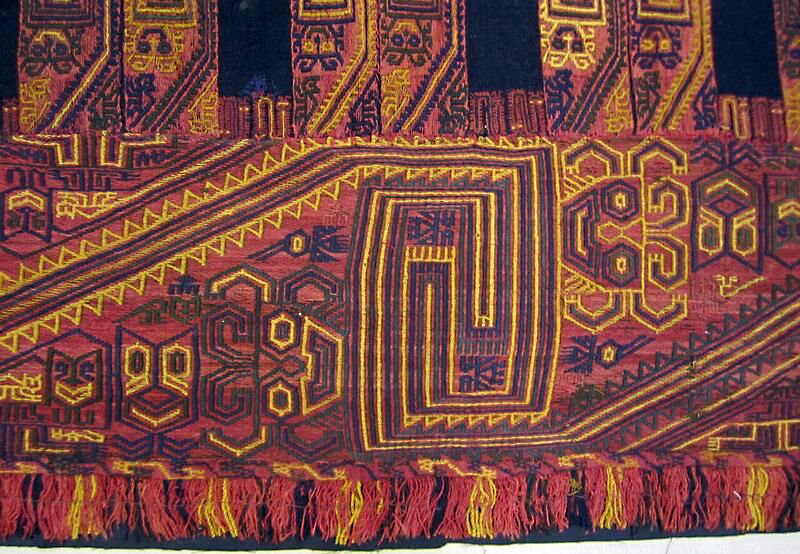

An introduction to Paracas culture: The major works of Paracas artists are a pinnacle of Andean textile art and acknowledged as among the most accomplished fiber arts ever created.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Cities and Sacred Spaces

Separating the secular and the sacred in the ancient Andes is not something that we can easily do. Many Andean cultures do not have a division between the world or worlds of ancestors and divine beings and the one we inhabit in our everyday lives. As such, we need to think about how architecture can be intended for a range of purposes we might currently think of as separate, and how structures can express their meaning. Is a building designed to invite people in or exclude them? Are there open spaces or are they enclosed? How might sound or other senses have been engaged by the architecture?

It’s also important to think about how architecture requires various kinds of resources. We can of course see the materials it is built out of, but we need to also think about the labor required—who might have constructed the building? Who might have directed the construction? Where might the building material have come from? Can we deduce systems of power from the size and amount of buildings in a place?

What other cultural practices might we figure out from looking at architecture?

Videos and essays about cities and sacred spaces

Caral: Caral’s plan and some of its components, including pyramidal structures and residence of the elite, show clear evidence of ceremonial functions, signifying a powerful religious ideology.

Read Now >

Chavín de Huántar: The location of Chavín between the desert coast and Amazon made it a key site for transmission of artistic style.

Read Now >

Complexity and vision: the Staff God at Chavín de Huántar and beyond: This image is so complex that its features could only be perceived, let alone understood, by the initiated.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Adorning the Body

How do we know who people are (or who they want to be)? Often, they tell us by what they wear and how they present themselves to us. Hairstyles, jewelry, skin decoration (permanent like tattoos or temporary like paint), in addition to clothing, are all methods of communication. They can tell us a person’s stage of life, their ethnic or national heritage, economic status, gender, and social role, or even if they belong to a particular fandom. This ability to communicate is something we often take for granted, but it is usually a deeply important part of a culture.

In the Andes, many different ways of adorning the body were used, from tattooing and even reshaping the crania of infants to headdresses and elaborate jewelry. But one of the most important materials for communicating identity was textiles.

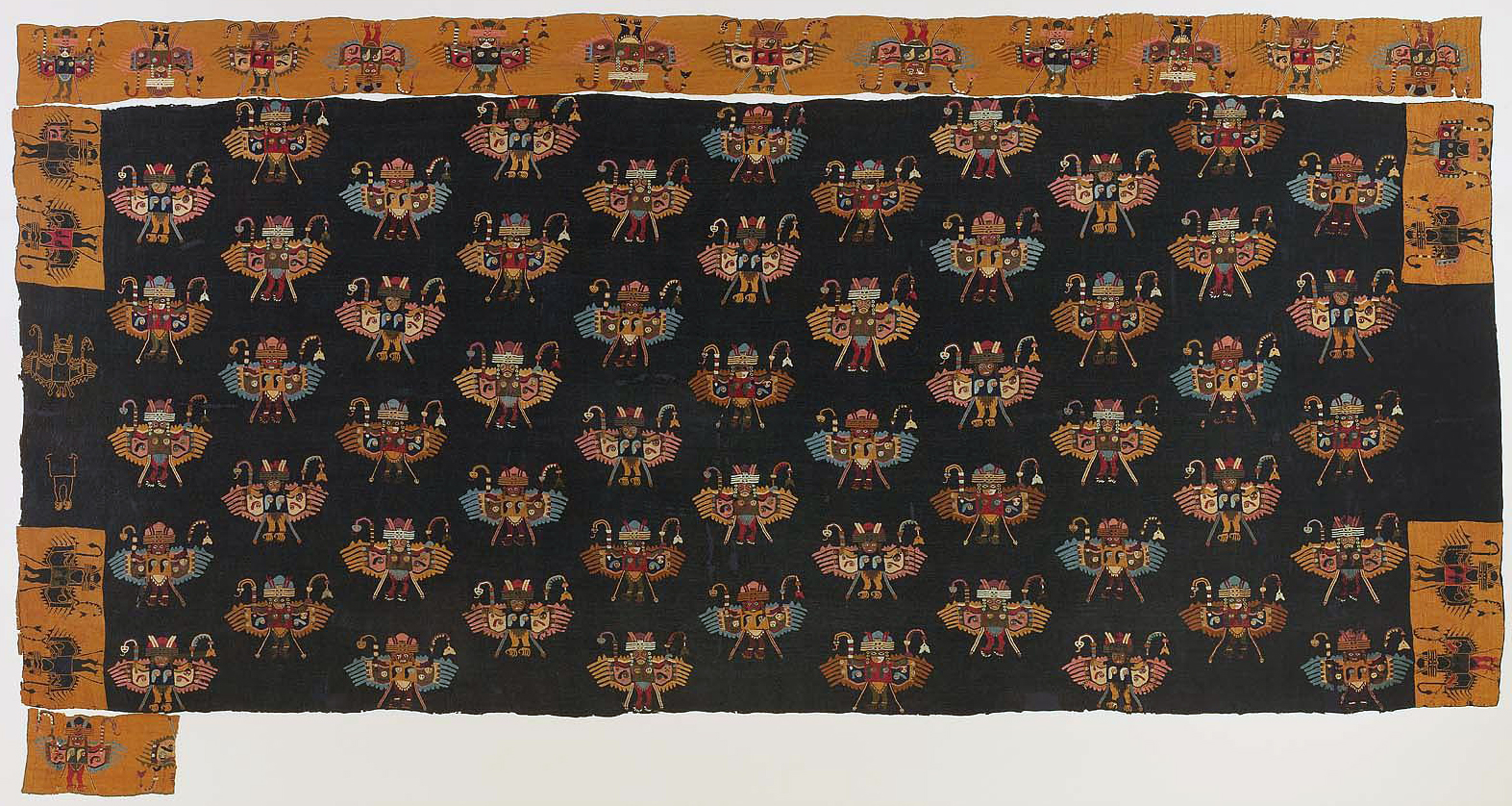

Man’s mantle and two border fragments, Paracas, 50–100 C.E., wool plain weave, embroidered with wool, 101 x 244.3 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

From very early on in Andean history, textiles were the most important element of what a person wore. Andean weavers developed some of the most sophisticated textile structures on Earth, and the process of preparing, dyeing, spinning, and weaving textiles should be thought of as a technology similar to the metallurgy used to make jewelry. Textiles communicated community membership, gender, social role, and power. Designs and weaving techniques were part of this, but so were kinds of fiber (cotton and camelid fiber were the usual materials) and dyes. Brilliant colors that were difficult to achieve were reserved for the highest elites, and clothing that used more than the minimum needed fabric spoke to wealth and power that could command labor.

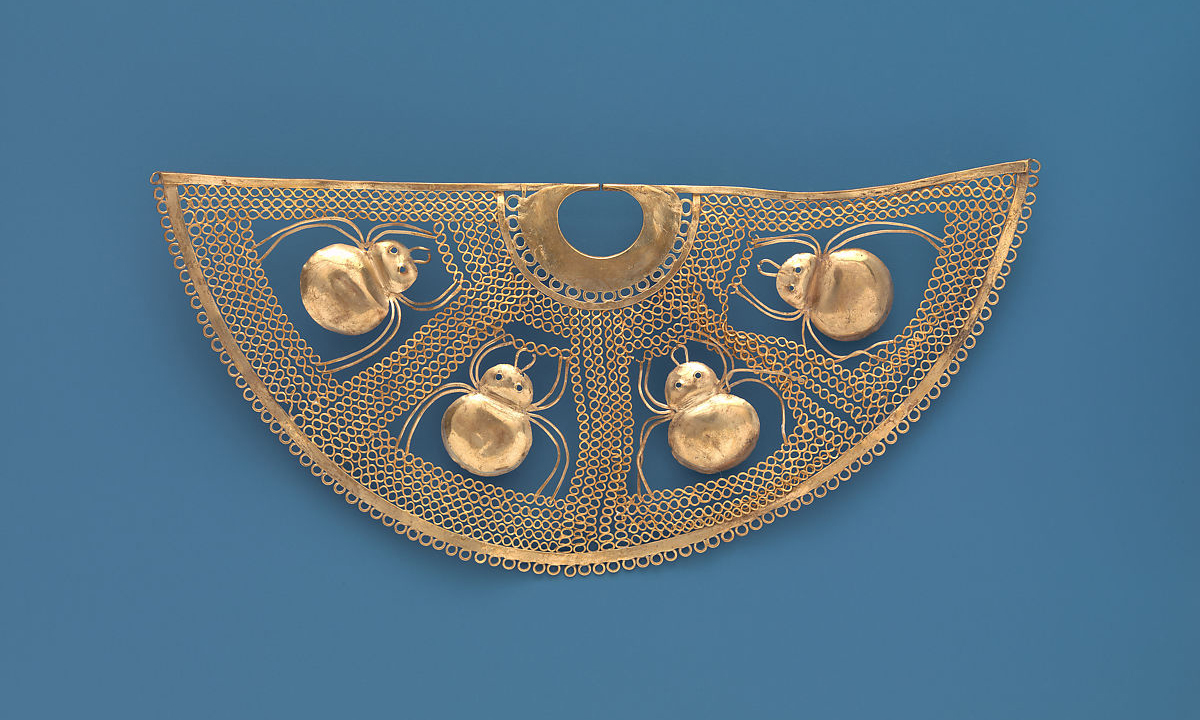

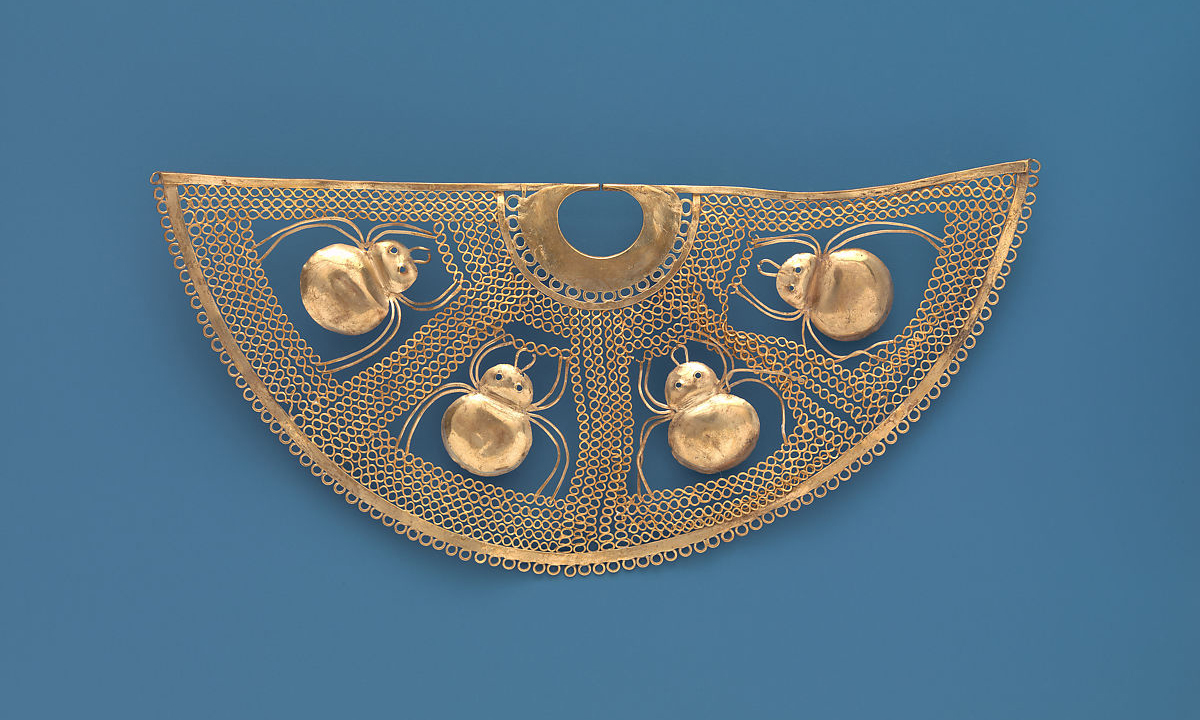

Salinar (?) culture, Nose Ornament with Spiders, 1st century B.C.E.–2nd century C.E., gold, Peru, North Coast, 5.1 x 11.1 x 0.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

But while people’s textiles relayed their social identity, so did jewelry. Gold was in early use in the Andes, due to both its easy workability and its brilliant shine, which we know later cultures associated with the sun. A person wearing brightly colored and expertly woven textiles and adorned with gold jewelry was immediately recognizable as someone of very high status. Add to that feathers from tropical birds that came from the cloud forests of the Andes mountains and the jungles beyond, and shells and stone beads imported from far away, and the wearer’s dazzling appearance would have instantly declared their position in society. Instead of designer brands or unique haute couture, Andean elites wanted sophisticated textiles and jewelry that adhered to the meaningful designs that people would recognize.

We are invited to think about how the ways people of the ancient Andes showed their identities through their appearance is similar to, and different from, today. Is there a universal way to think about identity, or is it always culturally determined? Is status always the most important thing appearance communicates?

Essays and videos about textiles and jewlery

Paracas textiles, an introduction: In Paracan culture, mummies were buried with lavish textiles.

Read Now >

Paracas Supernatural Bird Mantle: Paracas society may have been the first in the Andes to engage in avian-inspired ritual performance.

Read Now >

/3 Completed

Early ceramics

Spouted Bottle, Chorrera culture, Ecuador, 12th-4th century B.C.E., ceramic, diameter 6 inches, height 6 inches (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Like textiles and metalwork, ceramics also require complex technology to create. Knowing how to find and process clay into a material that will make the desired final product, what kinds of clay and other minerals will make the right colors when exposed to the heat of the kiln, how long and how hot to fire a piece, and finally how to create and sustain the temperatures needed to fire ceramics are all part of this technology. The result is an object that can be practical and everyday or special and laden with meaning (sometimes the everyday holds great meaning too: think, for example, about a pie plate that has been used for generations of one family).

Feline face bottle, Paracas, 4th–3rd century B.C.E., ceramic and post-fired paint, 17.8 x 14.3 x 13.7 cm, from the Ica Valley, Peru (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The ceramics art historians study tend to be special objects, meant for important uses like religious rituals, to be presented to a god, or to be buried with the dead for their use in the afterlife. Because they were often buried with the dead, they were kept safe from the elements and the stresses of use, making them more likely to be found whole; they were also usually very carefully made, lending themselves to study as art objects.

The durable nature of ceramics means that they survive far more often than textiles do, and their perceived lack of preciousness by outsiders meant that, unlike objects of valuable metal that were melted down later by treasure seekers in the years following the European invasion, they were not destroyed. Ceramics are one of the most common objects available to tell us about the lives and culture of the people of the Andean past. What might be the things that will persist in the future to tell others about us?

Essays and videos about bottles, bowls, and other vessels

Feline-Head Bottle: Multiple points of view are combined in the decoration of this vessel, tip it and see!

Read Now >

Paracas Feline Face Bottle: A jar with a feline face and bird spout can tell us a lot about the ancient Paracan culture of Peru.

Read Now >

Paracas Flying Figure Bowl: A flying figure and a cat animate this bowl from the ancient culture of Paracas, Peru.

Read Now >

Chorrera ceramics from Ecuador: Chorrera artists created elaborate vessels and highly expressive sculptural works.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Notes:

*Currently, there is only an introduction on Smarthistory to Paracas culture, but more introductory essays are planned.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did architecture in ancient South America shape the experience of people who encountered it?

What are some ways people of ancient South America communicated to others who they were?

What objects can we use to understand a society’s history and values?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did architecture in ancient South America shape the experience of people who encountered it?

What are some ways people of ancient South America communicated to others who they were?

What objects can we use to understand a society’s history and values?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

adobe

Andes mountain range

anthropomorphic

camelid

cochineal

Color Block Style

contour rivalry

earthwork

El Niño

geoglyph

Linear Style

mantle

Oculate Being

pyro-engraving

slip

Staff God

South America

stela

Learn more

Read the other two chapters about South America c. 2nd century–c. 900 C.E. and 800 C.E.–16th century C.E.