What work of art inspired you? Art historians answer.

Read Now >Chapter 1

Introduction: Learning to look and think critically (1 of 2)

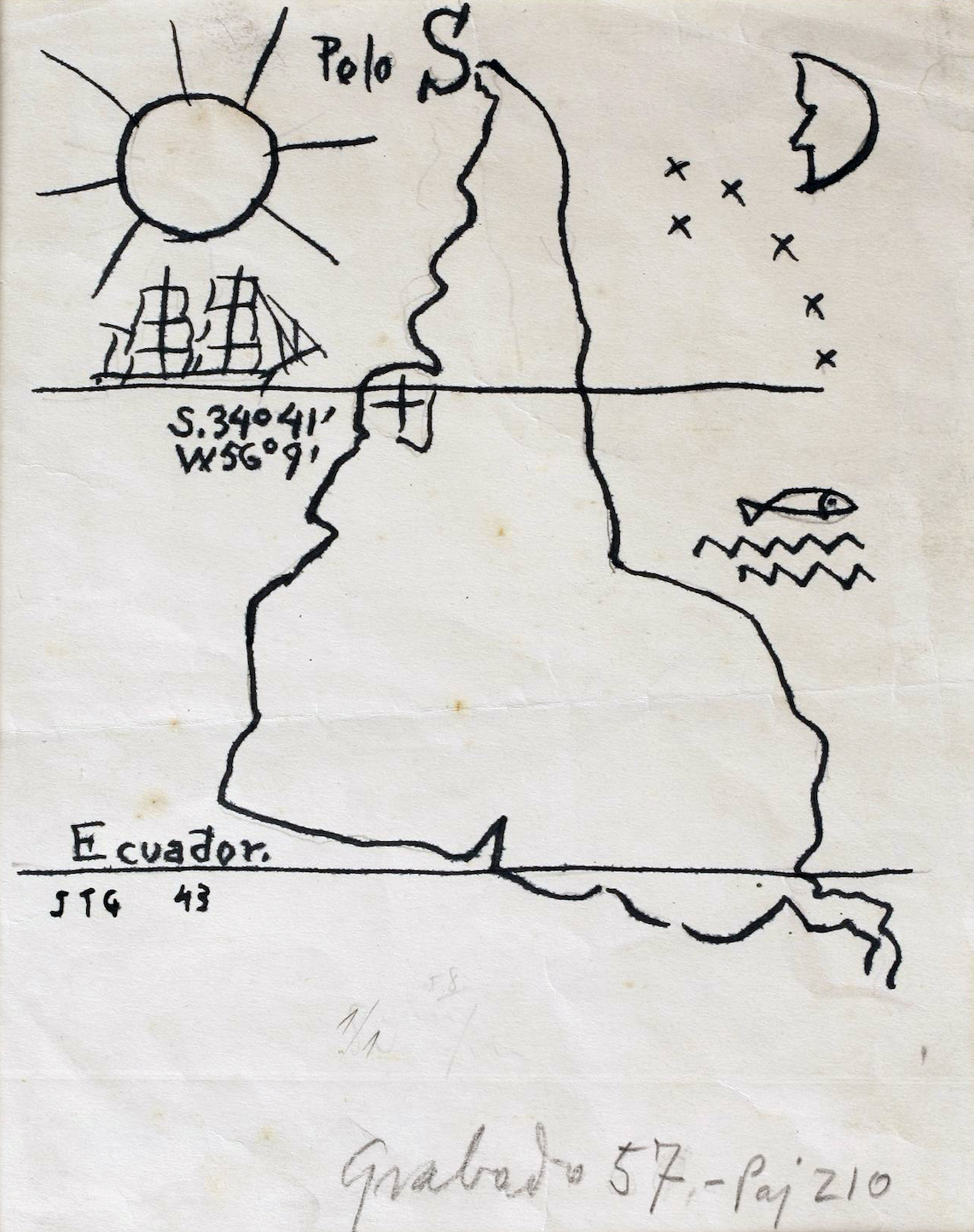

Joaquin Torres-García, América Invertida (Inverted America), 1943, ink on paper, 22 x 16 cm (Fundación Torres García, Montevideo)

Look closely at this drawing: what do you notice? Do you recognize any specific forms?

In his 1943 drawing América Invertida (Inverted America), Joaquín Torres-García shows the continent of South America turned upside down, with his home country of Uruguay positioned near the center in the top and middle third, and marked with a + and a horizontal line running through it. A prominent ‘Polo S’ at the top of the drawing refers to the South Pole. Why did Torres-García create this inverted map? At first glance, it might appear simple—a minimalistic ink drawing—but with close looking and a deeper understanding of how it relates to other maps and ideas, it becomes clear that the map is anything but simple. In a nutshell, Torres-García was aware of the power of images in constructing worlds and ideas. Let’s consider the map more closely.

Torres-García’s inversion of the South American continent might initially seem jarring—and that is intentional. We are accustomed to seeing maps in which the Northern hemisphere is positioned at the top, and the Southern hemisphere (including South America) is at the bottom. With his drawing, Torres-García wanted people to question why mapmakers defaulted to placing the Northern hemisphere at the top of maps, when in reality the universe is not structured this way—there is no up or down in space. By cleverly rotating the continent 180 degrees, Torres-García highlights the way that maps create meaning and hierarchies, even if we are led to believe that they are objective and free from bias. When he drew this inverted map, Torres-García had for years been trying to transform and overturn the idea that the so-called global north is more significant—that its art is more important and culturally relevant, its histories more complex, and its power greater. Torres-García directly challenged the hierarchy that North is better than South, and he called for South American artists to define art on their own terms rather than in relation to the United States and Europe in the North.

Perhaps you are wondering: why did Torres-García need to challenge the hierarchy of North-South in the first place? His image creatively engages with other maps that are deeply familiar to most of us—so familiar in fact that the view of the world they present has become deeply ingrained in our minds.

Mercator projection (map: Strebe, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The most common map in the world today is the one you see here (above), called the Mercator projection.

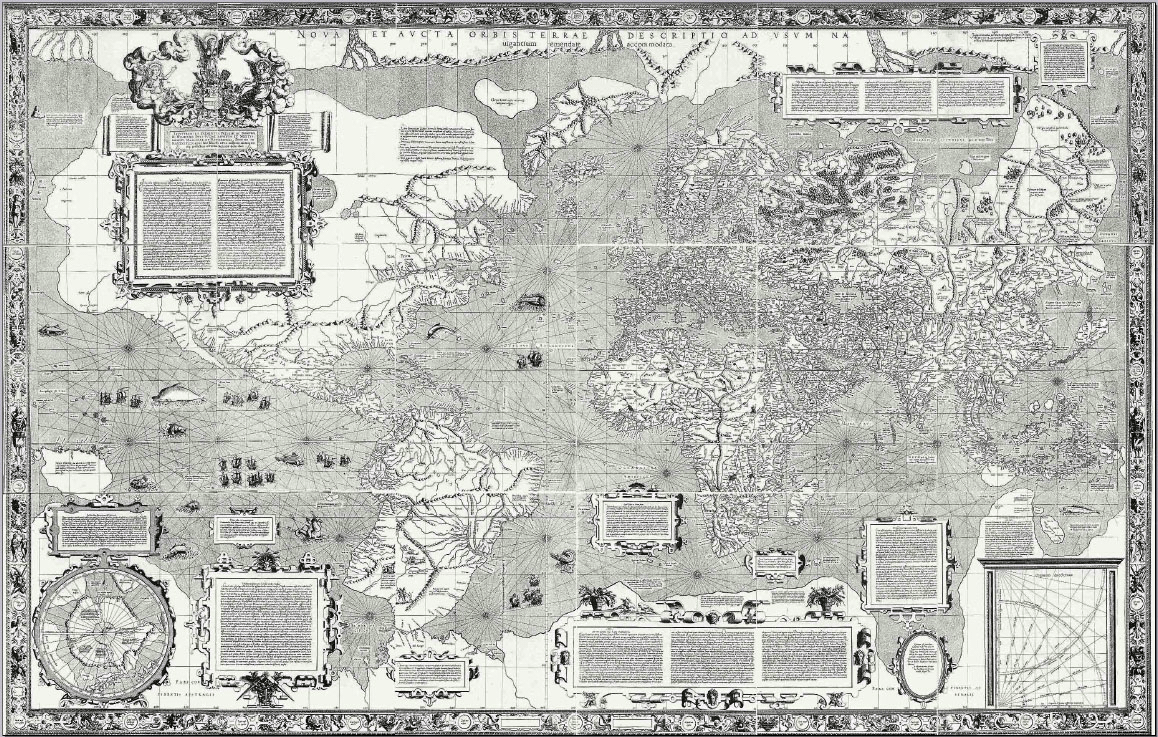

Gerardus Mercator, World Map, 1569

It is based on a map made in 1569 by the Flemish cartographer, Gerardus Mercator. Mercator’s earlier map transformed space in a way that would help western European navigators during the so-called “Age of Discovery,” as they explored lands for resources. These travels also led to invasions of lands beyond Europe (such as the Americas) and the eventual establishment of even more global trade routes, colonial settlements, and the transatlantic slave trade.

It was at this moment that Europeans oriented maps to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean was “centered” in world maps (a turn away from earlier European maps that were centered around Jerusalem, a city considered holy by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam). As normal as it might appear to us today, the Mercator projection—both the 16th-century original and the map we often see today—is actually heavily distorted, and does not represent the size of landmasses accurately. Take a look at South America on the Mercator projection (again, based on Gerardus Mercator’s earlier map) and compare it to Europe—they look similar in size. Likewise, Africa and Greenland are the same size.

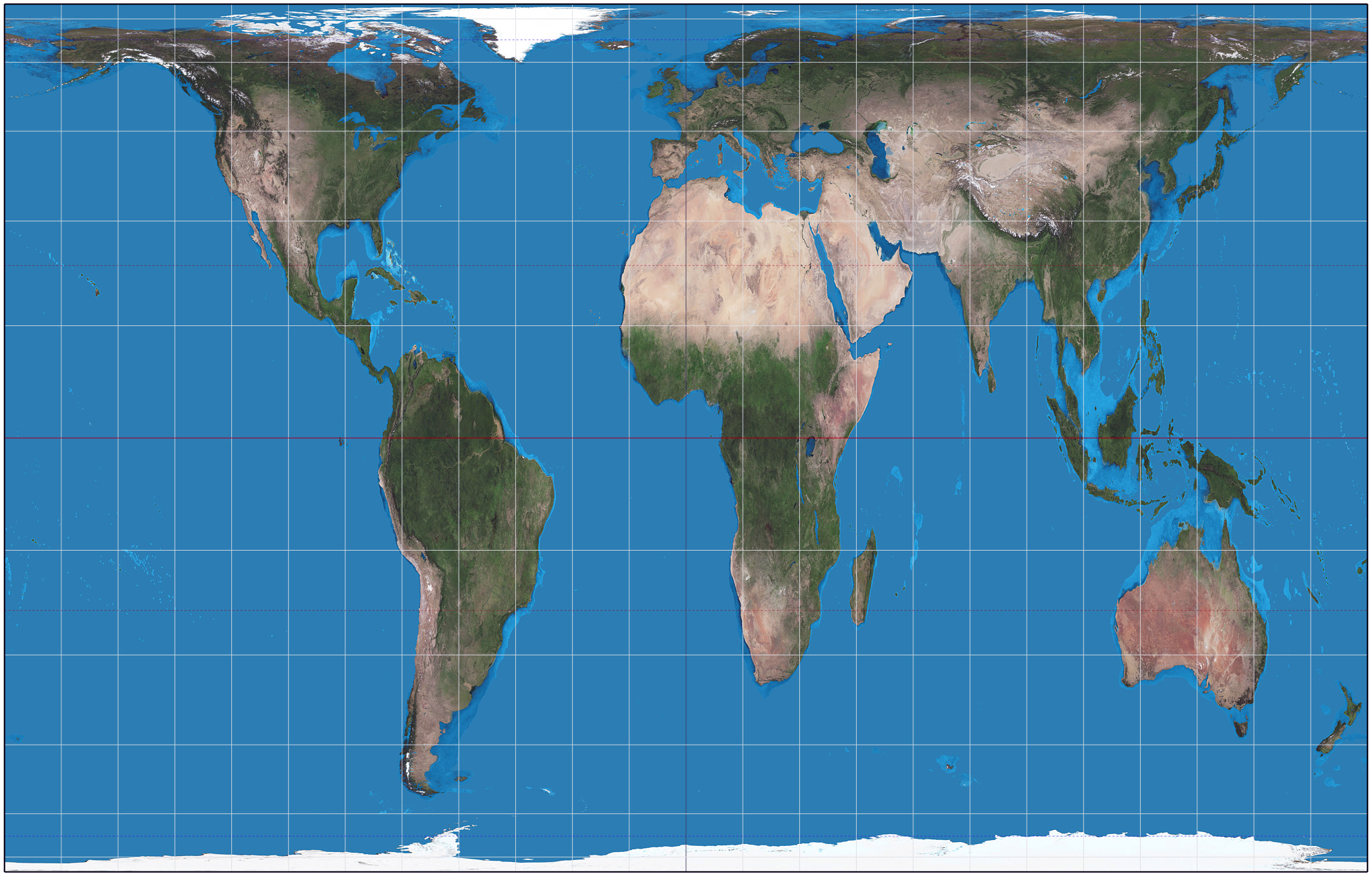

Gall-Peters projection (map: Strebe, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Gall-Peters projection is a more accurate representation of the size of landmasses—South America is double the size of Europe, and Africa is about fourteen times the size of Antarctica. [1] Torres-García’s Inverted Map calls attention to the problems and biases with mapmaking, and the values attached to places by their perceived size and location.

Torres-García’s map doesn’t just draw our attention to issues with mapmaking though. His drawing also critiques art history: His inversion prompts us to reflect on what is called the art historical canon—the set of art and architecture that over time has received the most attention and prioritization from art historians (and beyond!) and that has been codified as the most important to study and learn about.

We might ask though: who made these decisions? How and why did they make them, and even when were they making them? Whose stories are told, and who gets to tell them?

Rock-cut linga shrine in Cave 29, c. mid-6th century, Ellora, India (photo: Ronakshah1990, CC BY-SA 4.0)

For a long time, the canon privileged white, male, European and Euro-American art and artists; while that has started to shift, there is much more work to be done to create a more balanced, equitable history of art.

And it has not just been certain types of artists and places that have been privileged, but even certain types of media. For instance, while the canon has often celebrated bronze and marble sculpture, painted wood, alabaster, stucco, and even living rock-cut sculptures have proliferated among peoples throughout time in regions across the world.

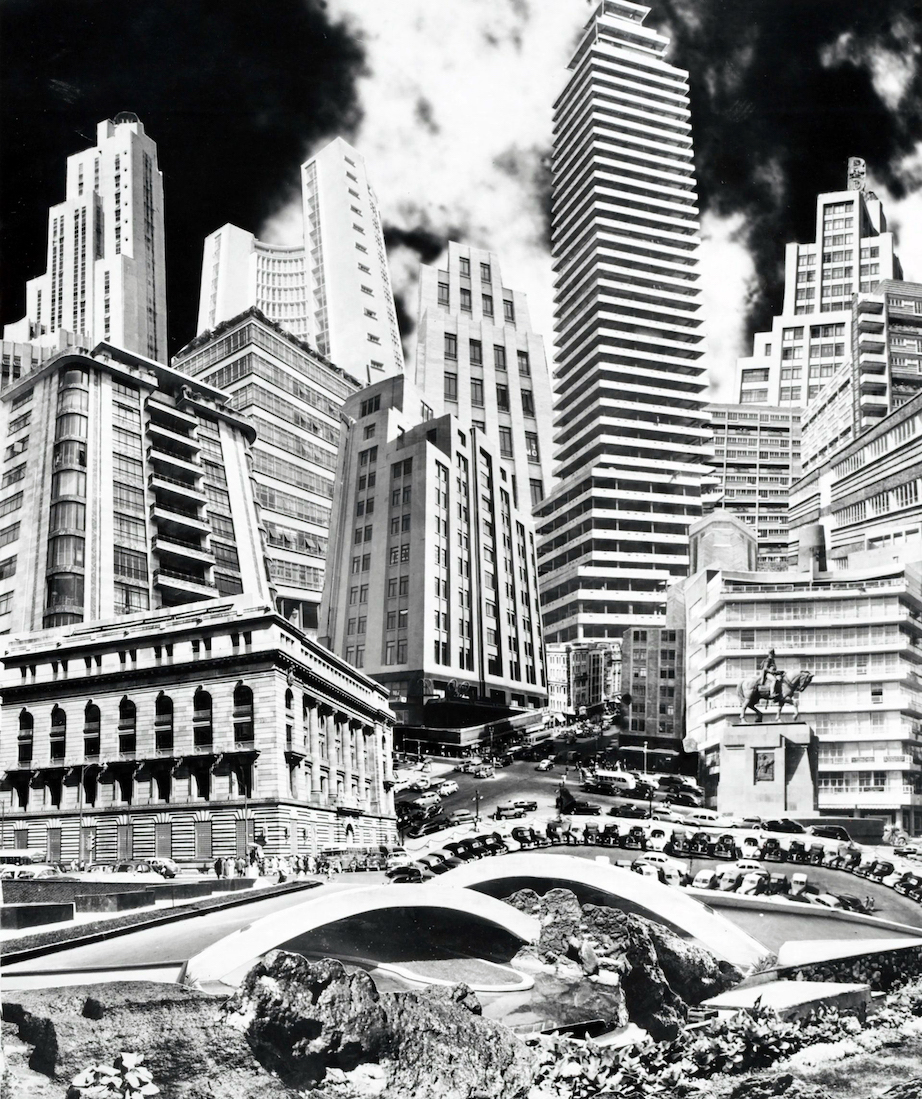

Lola Álvarez Bravo, Anarquía Arquitectónica en la Ciudad de México (Architectural Anarchy in Mexico City), 1954, gelatin silver print, 21.4 x 17.7 cm (© Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona Foundation)

Ideally, we could have an art history that not only highlights the marble sculptures of Roman emperors, Michelangelo’s David, or Picasso’s cubist paintings—but also bronze Shang dynasty ewers, the rock-cut churches of Lalibela and the caves of Ellora, the city of Cahokia, the modernist photographs of Lola Álvarez Bravo, and the contemporary Northwest Coast carvings of knowledge bearer and artist Nathan Jackson.

Torres-García’s reframing in América Invertida encourages us to not only look closely at what we see, but also think critically. It prompts us to pause and reflect on how certain geographic regions, art, and artists have been upheld as more important—and how those choices can exclude and marginalize people, or even distort how and what we think about the histories of art. The first time I saw Torres-García’s inversion as an undergraduate student I felt disturbed and even a bit uncomfortable, yet intrigued and reflective. For me, these varied reactions suggested that the image achieved its goal, and still today they remind me of why art and art history matters in the 21st century.

Sainte-Chapelle, Île de la Cité, Paris, 1248 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Art not only has the ability to provoke and disturb, but also to comfort and soothe, amuse and captivate. Prompting a different type of response than Torres-García’s small hand-drawn map, at least for me, is being enveloped by a space such as the Gothic Sainte-Chappelle in Paris. The physical experience of this space overwhelms me with its kaleidoscopic stained glass windows that soar upwards, showing more than 1,000 scenes from the Old and New Testaments. Why was it built, and what role did it play in the past and does it still play today? It was in fact a royal chapel, built to house precious Christian relics for the French monarchs, yet the gem-colored space is also a testament to the engineering innovations of the 12th and 13th centuries—delicate glass seems to hold up the building.

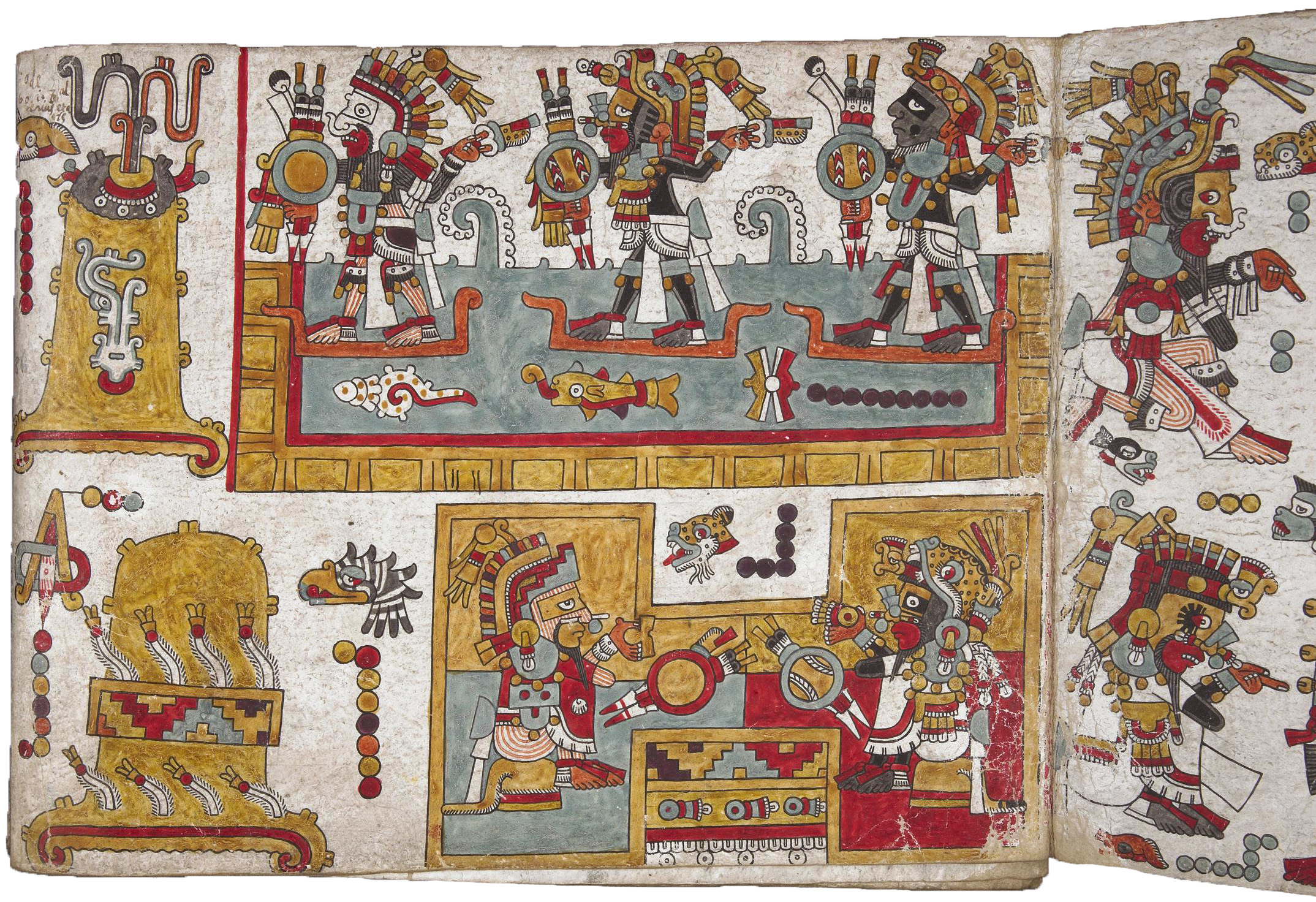

In part, the codex chronicles the life of Lord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw. Here, we see figures traversing water and sitting in an I-shaped ballcourt—all dressed in sumptuous clothing. Codex Zouche-Nuttall, 1200–1521, C.E., Mixtec (Ñudzavui), Late Postclassic period, deer skin, 47 leaves, each 19 x 23.5 cm, Mexico (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Being introduced to unfamiliar artworks can also spark our interest and curiosity in learning more about a culture’s art and history. As a sophomore Biology major in college, I took my first art history classes to fulfill General Education requirements. I will never forget the moment one professor displayed an image from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, made by a Mixtec (Ñudzahui) artist in what is today Mexico about the epic story of the ruler Lord 8 Deer Jaguar-Claw. I had never seen anything like it before (sadly). To begin to understand the complex picture-writing it involved and to dig deeper into stories and histories that were unknown to me, well, it was as thrilling then as it is today.

As you read this introduction, take a moment to see what catches your eye.

Kehinde Wiley, Rumors of War, 2019, bronze, 8.2 m tall x 4.9 m long (Richmond Museum of Fine Arts, Virginia)

In these toxic times art can help us transform and give us a sense of purpose. This story begins with my seeing the Confederate monuments. What does it feel like if you are black and walking beneath this? We come from a beautiful, fractured situation. Let’s take these fractured pieces and put them back together.

— Kehinde Wiley

Why does art and art history matter?

Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War looms above viewers, encouraging them to consider a more inclusive story of American art and history. The enormous sculpture was exhibited in 2019 in Times Square in New York City and now sits in front of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond. The bronze equestrian sculpture displays an African American man in Nike shoes, a hoodie, and jeans atop a powerful horse who rears upwards as the rider remains calm. The sculpture provides a counterpoint (and counternarrative) to the once-nearby sculpture of Confederate general J.E.B. Stuart. It also draws on centuries of paintings and sculptures of powerful white men on horses. Wiley’s sculpture, and the sculptures of Confederate leaders displayed in Richmond along Monument Avenue until recently, took on new layers of meaning in 2020 as conversations and public protests turned more pointedly to the question of why Black lives matter and to the role of art in public places. As sculptures of Confederate leaders and other white supremacists were toppled, defaced, or removed, many people continued to ask: what is the role of art in public spaces? Why should we care about art at all? How does art challenge problematic narratives or work to uphold them? Can art facilitate reconciliation? Can learning art’s histories make us more empathetic?

All-T’oqapu Tunic, Inka, 1450–1540, camelid fiber and cotton, 90.2 x 77.15 cm (Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C.)

Art, or at least the material objects and built spaces that we today refer to as “art,” has always been important. Still, the meanings attached to things and spaces have not only changed over time, but also are culturally constructed. For example, an Inka textile made of camelid fiber was worth far more (symbolically and materially) to them than objects made of gold or silver, and yet for the Spaniards who would invade and topple the Inka Empire in the 1530s, the metals were more desirable.

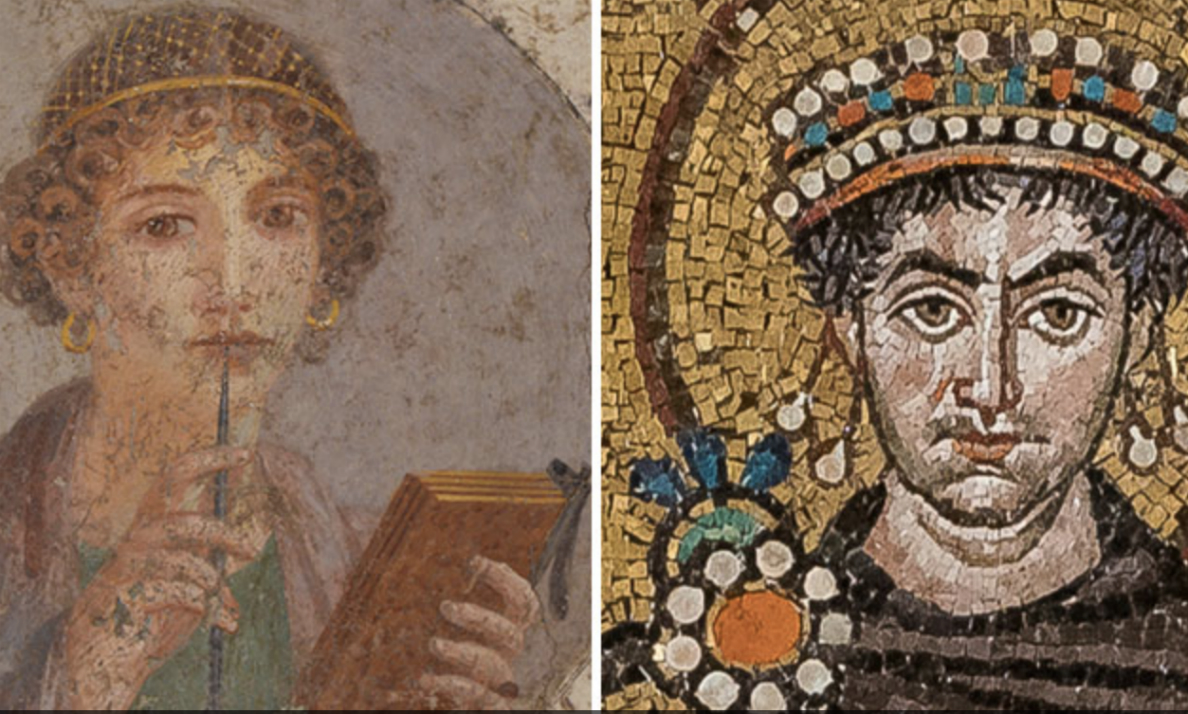

Left: Augustus of Primaporta, 1st century C.E., marble, 2.03 meters high (Vatican Museums) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: possible polychromy of Augustus of Primaporta

Another example would be the 18th- and 19th-century European and Euro-American interest in ancient Greek and Roman sculpture and architecture, prized in part for their supposed creation in white marble, which inspired new buildings and sculpture. Yet we know now that Greek and Roman sculpture used to be brightly painted in color. Still, individuals in the 18th and 19th centuries equated beauty with pure white marble, transforming how Greco-Roman art was understood and appreciated and establishing biased standards of what constituted “good” art and architecture across media. With the video below about Picasso’s Old Guitarist, you will also consider the idea of beauty, and how it too is culturally constructed (or even a personal preference).

Studying the histories of art is an engaging and important way to consider issues of identity, power and propaganda, race, gender, cross-cultural contact, discrimination and resiliency, spirituality, and more. As the many examples discussed in this textbook address, art did not and does not merely illustrate ideas, but actively encodes them. Moreover, for cultures that did not have a written language, the material and visual record is all the more important because it is the primary way in which we learn about them.

The following essays and videos address the issues raised here in more detail.

Short videos that introduce important issues in art history

Does art have to be beautiful? And just what is beauty anyway? Explore these questions with Picasso’s Old Guitarist.

Read Now >

What does it mean to be an “old master” and to make a “masterpiece”? The artist Kerry James Marshall discusses.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Introduction to art history and art historical analysis

Now that we have established why art and art history matters, let’s unpack in more detail what art history is (as a discipline or field of study) and how art historians analyze art. This section provides a foundation for what you will read and begin to do in your introductory art history classes and beyond. It also introduces you to more of the issues confronting art historians today.

Essays about art history

What is art history and where is it going? Methods change, the canon expands, and we write history anew. Too long focused on the West, the field is going increasingly global.

Read Now >

Art history and world art history: “Art history is relevant” is not how the discipline of art history is typically framed in popular discourse.

Read Now >

Introduction to art historical analysis: We can approach an artwork as a physical object, a visual experience, a cultural artifact—or as all three.

Read Now >/3 Completed

The skills you will learn studying art history are many—and lucky for us, they apply to any career path we might find ourselves on. Learning to look closely and to analyze the forms you are seeing is a useful life skill to think more critically about our intensely visual world (Social media! Advertisements! Movies! Video games! And so much more!), but it might also help you look closely as a medical doctor (diagnosing depends on the ability to describe what you see), graphic designer, website designer, or financial planner. Translating what you see into written or oral form is another skill—you will learn to articulate better what you see and to use more precise language to say what you mean. Writing about art will sharpen your compositional and communication skills—so useful in any career! Other skills you will develop or refine are maybe less obvious: engaging with art from across the globe, from different cultures, time periods, faiths, and more, inevitably helps us to deepen our empathy.

How museums and the art market shape meaning

Before we turn to a few useful approaches to analyzing art, it is important to consider how museums shape meaning. Many of us will at some point go to museums and engage with works of art on display from a museum’s collection or as a part of a traveling exhibition. Our encounter with art in a museum is not a neutral experience however, so it is useful to have some knowledge of how museums create narratives and even how collections can shape what we deem important. Some museums originated during periods of colonialism and imperialism, which is an important context to keep in mind not only for how a museum took shape, but also how an institution today may or may not acknowledge that legacy.

Figure from a Reliquary Ensemble: Seated Female, 19th–early 20th century, Fang peoples, Okak group, Gabon or Equatorial Guinea, wood, metal, 64 x 20 x 16.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A pointed example: the European colonization of much of the African continent in the 19th and 20th centuries resulted in the removal of objects from African nations to European collections; many of the objects chosen were ones that Europeans deemed most important or worthy of display, which has had a long-lasting impact on what survives today, what is taught as most important, and more. Read more about this in the essay below.

An essay about the reception of African art in the West

A “curiosity”? Initially, westerners saw African art as a mere “curiosity,” but this began to change with the advent of modernism.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Moreover, how an artwork is displayed in museums matters. Is it hanging on a wall, enclosed in a glass case, or elevated on a plinth? Is it alone on a wall or nearby to other artworks? What wall text (if any) accompanies it? What type of lighting and wall color surround an object? These are all choices that affect our experience and understanding of an artwork, and help us to think about what narrative or meaning is created by its display. Likewise, how art is presented to us in other contexts—perhaps on Instagram, in someone’s house, or on the street—shapes what we think about art (or whether we might even label it as ‘art’), and can do so in very different ways.

Leonardo da Vinci or not? Salvator Mundi, c. 1500, oil on panel, 45.4 cm × 65.6 cm (Louvre Abu Dhabi)

We might also consider the ways in which the contemporary art market shapes meaning: why do some artworks sell for record numbers? Does their high monetary value make them more valuable and worthy of consideration than other objects? Consider the Salvator Mundi painting that sold for more than $450 million in 2017, and which is attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. While some scholars do believe that Leonardo painted it, others dispute the attribution, and it has led to some, such as FBI art crime specialist Robert King Wittman, to say “Why anyone would pay that kind of money for a piece that had questions about it is very strange.” [1] Still, it is indisputable that the mere idea that Leonardo touched it led to the painting being valued more highly than others, even with the murky attribution. But should it be? In a video below, you will also learn more about the art market’s relationship to museums and its connection to tax write-offs—two other factors to keep in mind about the art market’s impact on what a society deems important.

Read essays and watch videos about museums and the art market

How do museums shape meaning? The architecture of museums has long been used to shape national identity, and to frame collective memory.

Read Now >

“It is to kill art to make history of it”: Learn about the neutralizing effect of the art museum.

Read Now >

The art market, an introduction: it is one of the many ways rich people game the system to save billions of dollars in taxes each year.

Read Now >/3 Completed

What is cultural heritage?

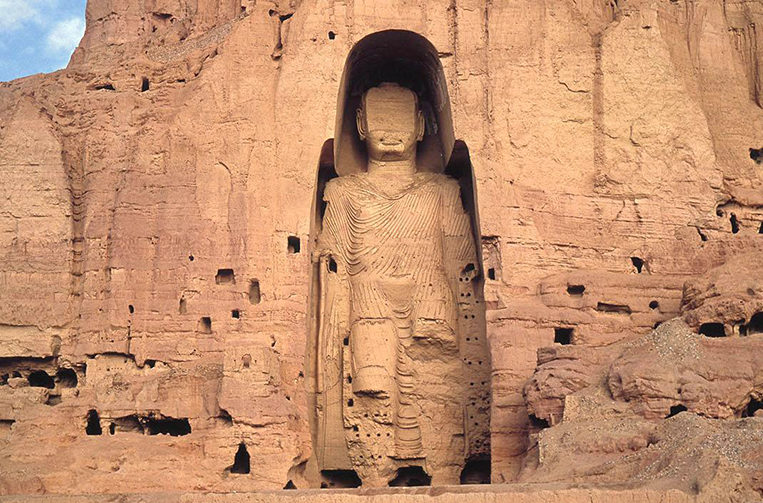

In 2001, the famous, monumentally sized rock-cut Buddhas of Bamiyan, Afghanistan were blown up on live T.V. by the Taliban, sending ripples of shock, anger, and sadness across the globe.

West Buddha surrounded by caves, c. 6th-7th C.E., stone, stucco, paint, 175 feet high, Bamiyan, Afghanistan, destroyed 2001 (photo: © Afghanistan Embassy)

Why destroy these sculptures that were over 1,000 years old? And what have we lost with their destruction? In 2012, in a less public example, northern Mali was taken over by Tuareg and Islamic separatists. According to UNESCO, historic mausoleums were destroyed, and more than 4,000 manuscripts were burned. About 300,000 manuscripts were also made vulnerable to illicit trafficking. These examples are unfortunately only two of many, yet they raise important questions and issues about what we call cultural heritage, explained in depth in an essay below. How can we protect cultural heritage from existing threats? And importantly, who “owns” cultural heritage? The examples also testify to the power and importance of art—even if it is thousands of years old.

Essays about cultural heritage

What is cultural heritage? Whose property is it anyway? Even when we’re talking about humanity’s greatest achievements, institutions disagree.

Read Now >

“Culture in crisis”? The word “crisis” suggests a temporary problem—but destruction and loss of cultural heritage is an ongoing issue.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Hopefully by the end of part 1 of this introduction you feel more empowered about what some of key issues are in art history today. The second part of this introduction will provide some basic approaches to looking at and analyzing art—and will demonstrate the importance of close looking.

Read the second part of this introduction

Notes:

[1] Dalya Alberge, “How did a £120 painting become a £320m Leonardo … then vanish?” The Guardian, 13 June 2021

This chapter benefitted from the critical insight and feedback from Sarahh Scher, Maya Jiménez, Heather Graham, Olivia Chiang, Rachel Zimmerman, Laura Tillery, Jeffrey Becker, Beth Harris, and Steven Zucker.

Key questions to guide your reading

Why does art and art history matter?

How do museums and the art market shape meaning?

What is cultural heritage, and why does it matter?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhy does art and art history matter?

How do museums and the art market shape meaning?

What is cultural heritage, and why does it matter?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

art history

museum

cultural heritage

art market

medium (pl. media)

style

subject matter/iconography

function

Learn more

Collaborators

This chapter wouldn't exist without all of the wonderful individuals and institutions (listed below) who developed high-quality, thought-provoking open-access materials that I am able to link to in this chapter. And of course the ideas contained within it are ones shaped by many excellent conversations, readings, presentations, and more. Thank you to everyone who helped to shape this introduction (and book!).