The Inka, an introduction: The Inka empire spanned from Ecuador to Chile, and was connected by a road system used for official business only.

Read Now >Chapter 31

Late South America (c. 800 C.E.–16th century C.E.)

Introduction

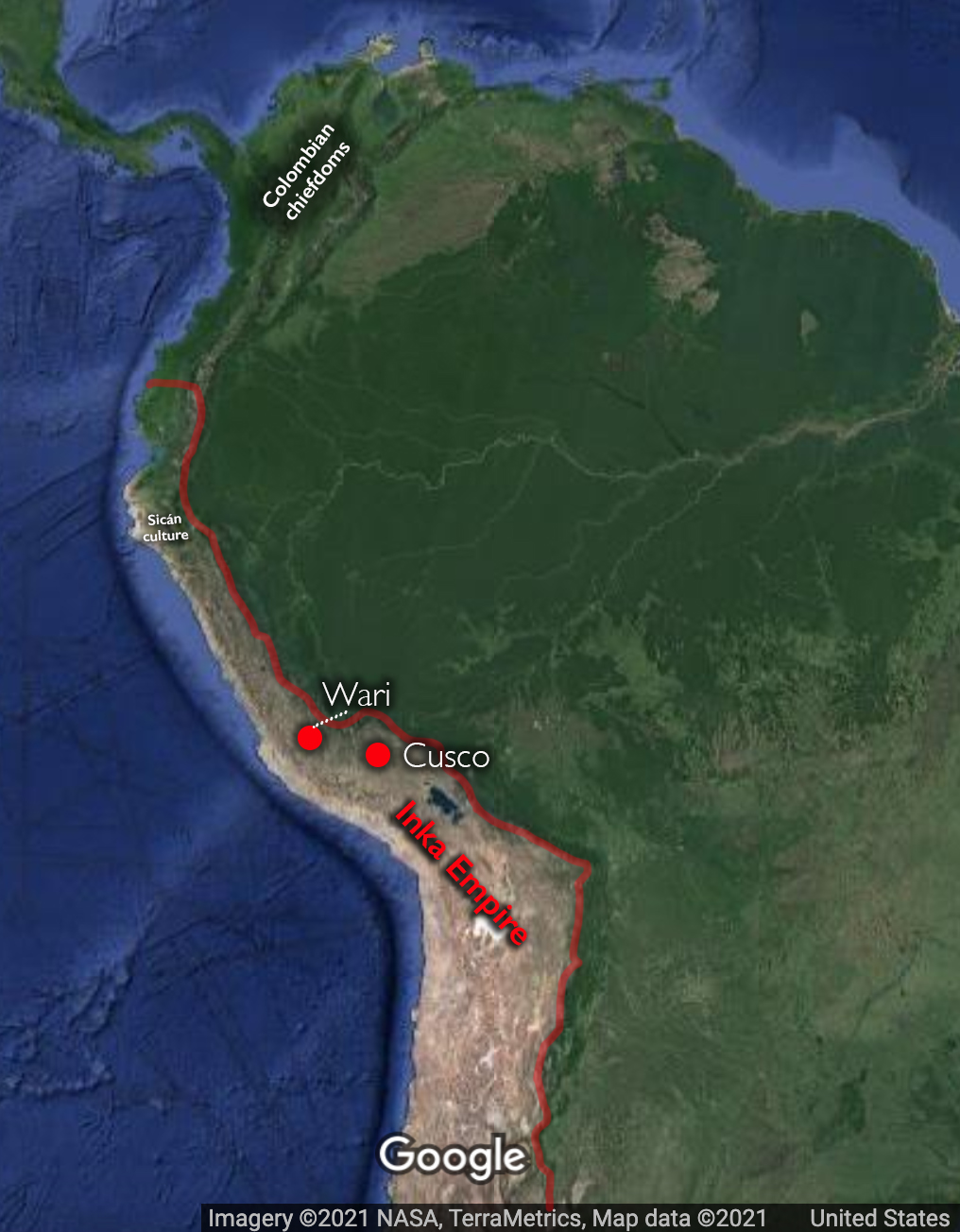

How do we know who’s in charge? Establishing and maintaining status and power are important to rulers in both large and smaller-scale societies, and artworks can be an important part of expressing that status. A chief needs to signal status just as much as an emperor does, and it’s possible that if we looked at them out of context we might not be able to tell them apart. As we look at the groups from the Andean region of South America in this chapter (from the Sicán and Wari cultures to the Inka empire) who worked to expand their territory through conquest and assimilation, we also need to think about places where such expansion did not take place.

Map of South America with cultures and cities indicated (underlying map © Google)

In contrast to the conquest and territory-grabbing of the Inka we have the chiefdoms of Colombia, which were smaller and more culturally homogenous, but no less inventive or concerned with the power and status of individuals. In contrasting the broad set of topics in the Inka cultural introduction with the introduction to Colombian goldsmithing, we move from a view of imperial statecraft to the personal display strategies of chiefs and their nobles.

This chapter addresses four topics:

- cities and sacred spaces,

- adorning the body,

- drinking and enacting status, and

- empire and agriculture.

Khipu, Inka, 1400–1532, cotton, 39 x 77 cm (The Brooklyn Museum)

All of these topics are united by their relation to the expansive states of the late period, and the way that power was created, asserted, and perpetuated. While the chiefdoms of ancient Colombia were much smaller than the Wari and Inka empires, they nonetheless also were interested in making power visible, so that those subject to it knew their place in society. In addition, the introduction tells us about the Inka khipu—a fiber device used to record many kinds of information, which was used by the Inka to keep track of the people and goods under their control. The maize grown by the people who used the paccha below would have been recorded on a khipu, along with the taxes they paid. Sometimes, power is seen in the ability to commission and control information, and with the khipu, we see a unique way of storing that information.

Read and watch these introductory materials

Ancient Colombian goldmaking: For centuries Europeans were dazzled by the idea of a lost city of gold in South America . . . but did it really exist?

Read Now >/3 Completed

Cities and sacred spaces

Remains of the Qorikancha, Inka masonry below Spanish colonial construction of the church and monastery of Santo Domingo, Cusco, Peru, c. 1440 (photo: Angela Rutherford, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

As we have seen in previous chapters on Andean art, cities in the ancient Andes often combined aspects of sacred and secular space, and sometimes the two combined in ways we might not have expected. In looking at two Inka spaces (the Inka capital city of Cusco and the royal estate of Machu Picchu), we can see in large and small scale how the Inka thought about landscape and architecture.

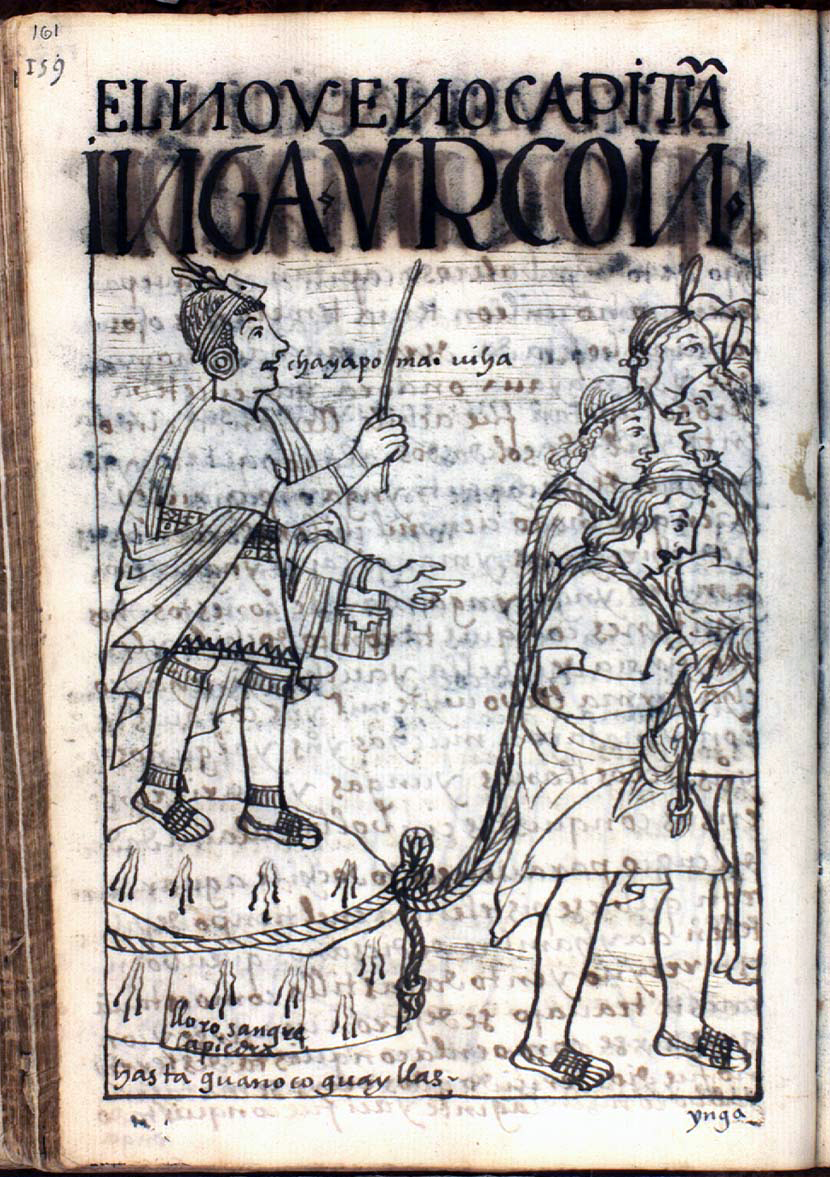

A sayk’usqa stone cries tears of blood as it is dragged (seen on the lower left), from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615, p. 161 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

In Inka thought, stones and humans could be interchangeable (such as we see in a colonial manuscript page from Guaman Poma’s New Chronicle and Good Government), and so using stone to build their cities carried implications about building groups of people. Like the stones of Inka walls, people were supposed to fit together for the common goals of the Inka empire. While this wasn’t always how things worked (the Inka spent a lot of resources on keeping conquered peoples in check), it was the projected idea of social harmony that was embodied in Inka walls. The very fabric of Inka architecture was also propaganda for compliance with the Inka state.

Machu Picchu, Peru, c. 1450–1540 (photo: Sarahh Scher, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Like the ciudadelas (citadels) of Chan Chan (discussed in an earlier chapter), the Inka royal estate of Machu Picchu is a statement of power and exclusivity. It was a pleasant, beautiful location and served as a place for the Inka emperor to get away from the capital. Yet it also contained elements that underscored the religious obligations of the nobility, and Inka beliefs in a sacred landscape. Cusco, as the political center of the empire, was also its spiritual center. At its heart, the Qorikancha (discussed in the essay below about Cusco) was dedicated to Inti—the sun god, main deity, and ancestor of the Inka royal line. How do we define sacred spaces in our world today? How do we use architecture to do this?

Essays about cities and sacred spaces

City of Cusco: It has been argued that Cusco was laid out in the shape of a puma, symbolizing Inka might.

Read Now >

Machu Picchu: The Inka emperor hosted feasts, performed religious ceremonies, and ruled his empire from this remote citadel.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Adorning the body

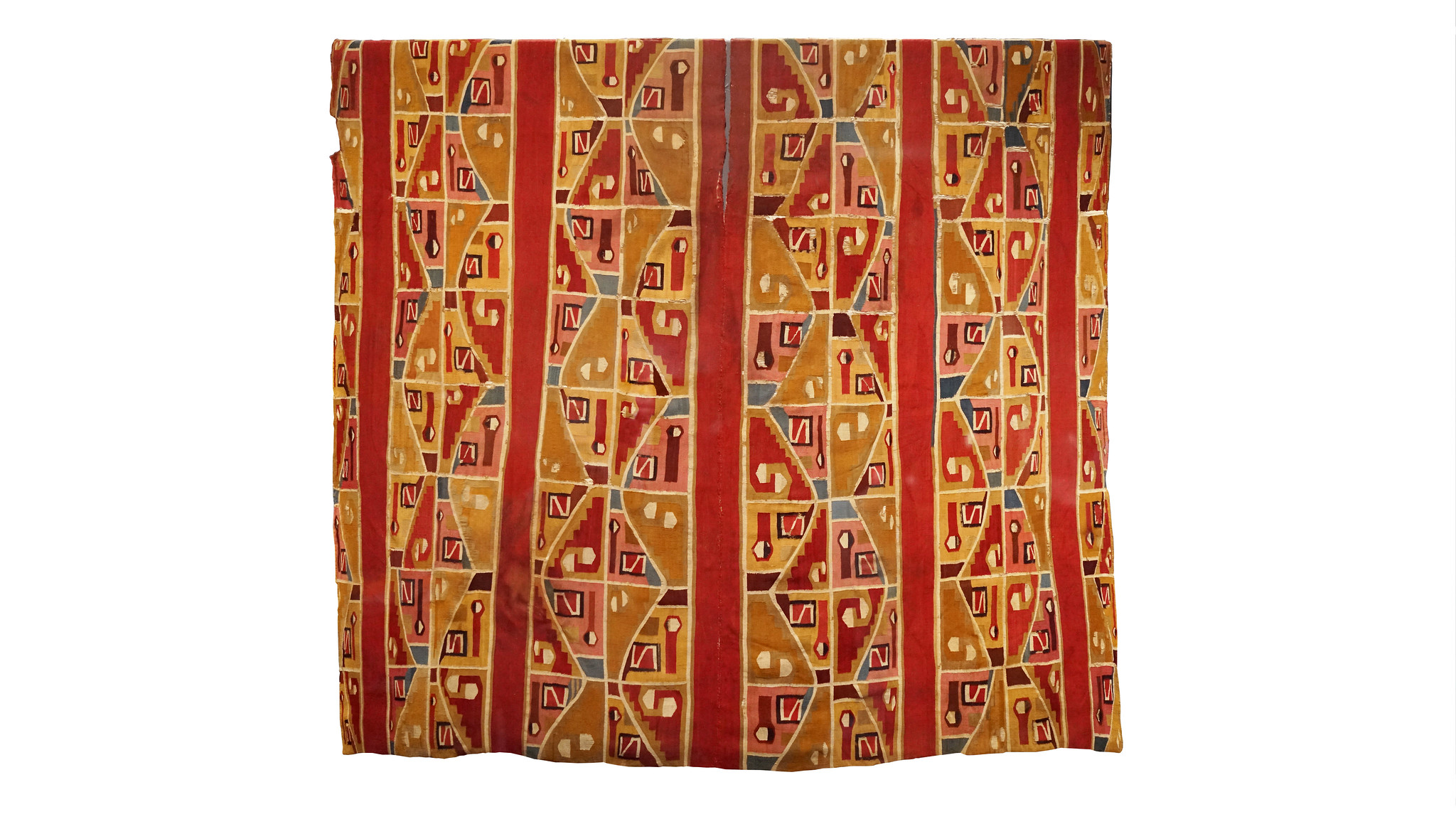

Tunic (Wari, Peru), c. 600–850 C.E., wool, cotton (interlocked tapestry weave), 109.9 × 118.1 cm (Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design)

As the previous two chapters have shown, the things people wore helped show who they were. In the Andes especially, textiles were the ultimate measure of a person’s social status. Even though everyone wore clothes made of cloth, the kind of fiber, use (or lack) of dyed color and pattern, and weave all worked to show a person’s place in the culture. The textile objects discussed below show different forms of high-status textiles, a hat and tunics. Nonetheless, they share certain elements in common: the use of camelid fiber and color as a marker of status, and the wearing of these objects being restricted to certain people within the society.

Muisca Raft, 600–1600, cast gold alloy, Museo del Oro (Gold Museum), Bogotá, Colombia

The raft model from Colombia helps us think about the use of gold adornment in Muisca culture, the ultimate expression of which was the ritual of chiefly accession that led to the Spanish legend of El Dorado, “the golden one,” in which a new chief was covered in gold leaf before being submerged, along with his raft and offerings, into a sacred lake, from which he emerged as the new ruler. The association of gold with the sun helped signify the relationship rulers had with the divine.

All-T’oqapu Tunic, Inka, 1450–1540, camelid fiber and cotton, 90.2 x 77.15 cm (Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C.)

Materials that a culture holds in high esteem are used to show the unique and sometimes supernatural qualities of a ruler. In the ancient Andes, that was textile, which was prized more than gold (a valuation that perplexed and frustrated the Spaniards who overthrew the Inka empire). The relationship between humans and the camelids that provided the fiber, and the plants, minerals, and insects that provided the dyes was thought of as becoming a part of the spirit a textile acquired as the dyed fibers were spun and woven. Cloth therefore had a life that then was joined with that of the ruler or elite person who wore it. While, similarly to the Muisca, the Inka associated gold with the sun god (whom they called Inti), the Inka chose to sacrifice textiles to Inti—a choice that points out how valuable these textiles were. Objects made of gold, if they survive looting and plunder, are much more sturdy than textiles and can survive in conditions that will cause organic materials to disintegrate. For that reason, many people think of the ancient Andes as a land of gold, when in reality it was a land of cloth. How much do we think of textiles in our day to day lives? What qualities do we want in them? Does gold have the same or different meanings now than it did in the ancient Andes? How do we decide what is valuable and what isn’t?

Essays to read and watch about adorning the body

Four-cornered hat: Learn more about how the Wari people made incredibly complex, detailed textiles like this hat

Read Now >

All-T’oqapu Tunic: Andean cultures had long valued textiles, but they were especially significant and finely-made in the Inka Empire.

Read Now >

Muisca Raft: The Muisca would honor a new leader by covering his body in gold dust and then submerging him, his raft, and other offerings into the sacred lake.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Special objects that signify rulers have been used in cultures across the globe, from the Crown Jewels of England to the gold and jade crown from ancient Korea, which is given here as a comparison.

A cross-cultural comparison

Gold and jade crown, Silla Kingdom, Korea: With its gold branches, this crown evokes a sacred tree.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Drinking and enacting status

Inverse-Face Beaker, 10th-11th century, Sicán (Lambayeque), Peru, gold, 20 x 18.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

What does it mean to accept a drink from someone? In the ancient Andes, it often meant accepting a subordinate place in the system of power. A kind of beer made from maize called chicha was more than just a social drink, it was an important part of how rulers reinforced the social obligations they had to their subjects, and more importantly, the obligations their subjects had to them. Rulers would, at certain times of year, throw feasts for their subjects, who would gather for food, drink, and important rituals that cemented social bonds among the living, the living and the dead, and humans and the supernatural. For formal rituals of drinking, cups were often made in pairs, with one smaller than the other. The larger vessel was for the chief, lord, or other social superior, while the smaller one was for the subject or vassal. By accepting the smaller vessel handed to them, the subordinate signaled their understanding and acceptance of their place in the social order. Sometimes, rulers and ritual specialists would also “drink” with the gods or with the ancestral dead. They would pour chicha out of one vessel and drink from the other, cementing their ties with the powers that helped shape the fate of their people.

Keru (Inka), 15th–early 16th c., wood, height: 5 3/4 in. (14.6 cm) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Below, you will learn more about a Sicán beaker and the Inka keru (or qero), both of which are objects from this drinking tradition. The Inka kerus we see in the article below are made of wood, but we know that Inka elites drank from gold and silver vessels, with gold being reserved for the emperor. Are there any rituals involving food or drink that have similar meanings in the modern world?

Essays and videos about drinking and status

Inverse-Face Beaker, Sicán: Feline fangs, rather than human teeth, suggest that this figure is either supernatural or in contact with deities.

Read Now >

Keru Vessel: Although this vessel depicts a royal Inka couple, it was produced after the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Empire and agriculture

A hungry populace is, paradoxically, one that is physically weak but sometimes defiantly powerful. People who are not taken care of by their government may decide to rebel against it—something ancient Roman rulers knew well, and the poet Juvenal commented on; by offering “bread and circuses” (food and entertainment) to keep the common people distracted, they kept them from becoming more invested in the politics of Rome. Inka rulers similarly knew that an empire that was productive agriculturally was strong, and that a ruler (and his bureaucracy) who could transport food aid from places of plenty to places in need was one who would have a better hold on its populace.

To this end, the Inka empire maintained an extensive network of storehouses along its expansive royal road system. Beautifully engineered, these structures helped keep out pests while preventing food from rotting. Freeze-dried potatoes (called chuño in Quechua, the Inka language); dried maize; salted, dried meat (called ch’arki, from which we get the word “jerky”); and many other foods were kept in these storehouses. Their supplies were used to feed officials and messengers traveling along the Inka roads, but could also be redistributed in times of need.

Maize cobs, Inka, c. 1440–1533, Sheet metal/repoussé, metal alloys, 25.7 x 6 x 9 cm (Ethnological Museum, Berlin) (photo: Ethnological Museum, Berlin, CC BY-NC-SA)

To fill these storehouses, the Inka needed successful harvests, and they used not only their farming expertise but supernatural aids to achieve them. The paccha and maize cobs discussed below both were part of the ritual practices of the Inka empire that were meant to gain the spiritual world’s favor. The paccha and cobs center on maize, which was a ritually important food, as we have seen in the discussion of the drinking vessels above. It was (and is still) also a food that is easily dried and preserved, making it ideal for storage and transport if needed. Part of the way the Inka demonstrated their hold on the lands they conquered was by showing that they held an important supernatural influence on the earth itself and its productivity; these two objects are a part of that “spiritual statecraft.” Aside from military power, how do governments get their people to go along with their plans? What things do we think modern governments need to provide to their people?

Essays about empire and agriculture

An Inka paccha: The ritual this was made for was enacted in fields the Inka owned—in the Chancay lands they had conquered.

Read Now >

Maize cobs: A life-size metallic garden at the Qorikancha included these corn cobs, llamas, and other offerings.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Key questions to guide your reading

How did people and organizations maintain and display their power?

How did people in the past dress to show power? How does that compare to today?

How did people create social bonds?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did people and organizations maintain and display their power?

How did people in the past dress to show power? How does that compare to today?

How did people create social bonds?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

The Andes

axis mundi

camelid

ceques

chicha

cochineal

goldsmithing

hanan

hurin

keru (or quero)

khipu (or quipu)

maize

paccha

qompi

Quechua

slip

Tawantinsuyu

toqapu (or tocapu)

tumbaga

tunjo

Learn more

Read the two earlier chapters on South American art, from c. 3000 B.C.E.–2nd century C.E. and c. 2nd century C.E.–c. 900 C.E.

Learn more about Guaman Poma’s New Chronicle and Good Government in this essay or see his entire manuscript online