The Crac des Chevaliers (Krak des Chevaliers) was built by the Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem from 1142 to 1271. With further construction by the Mamluks in the late 13th century, it ranks among the best-preserved examples of the Crusader castles.

Chapter 37

Material culture of the Crusades

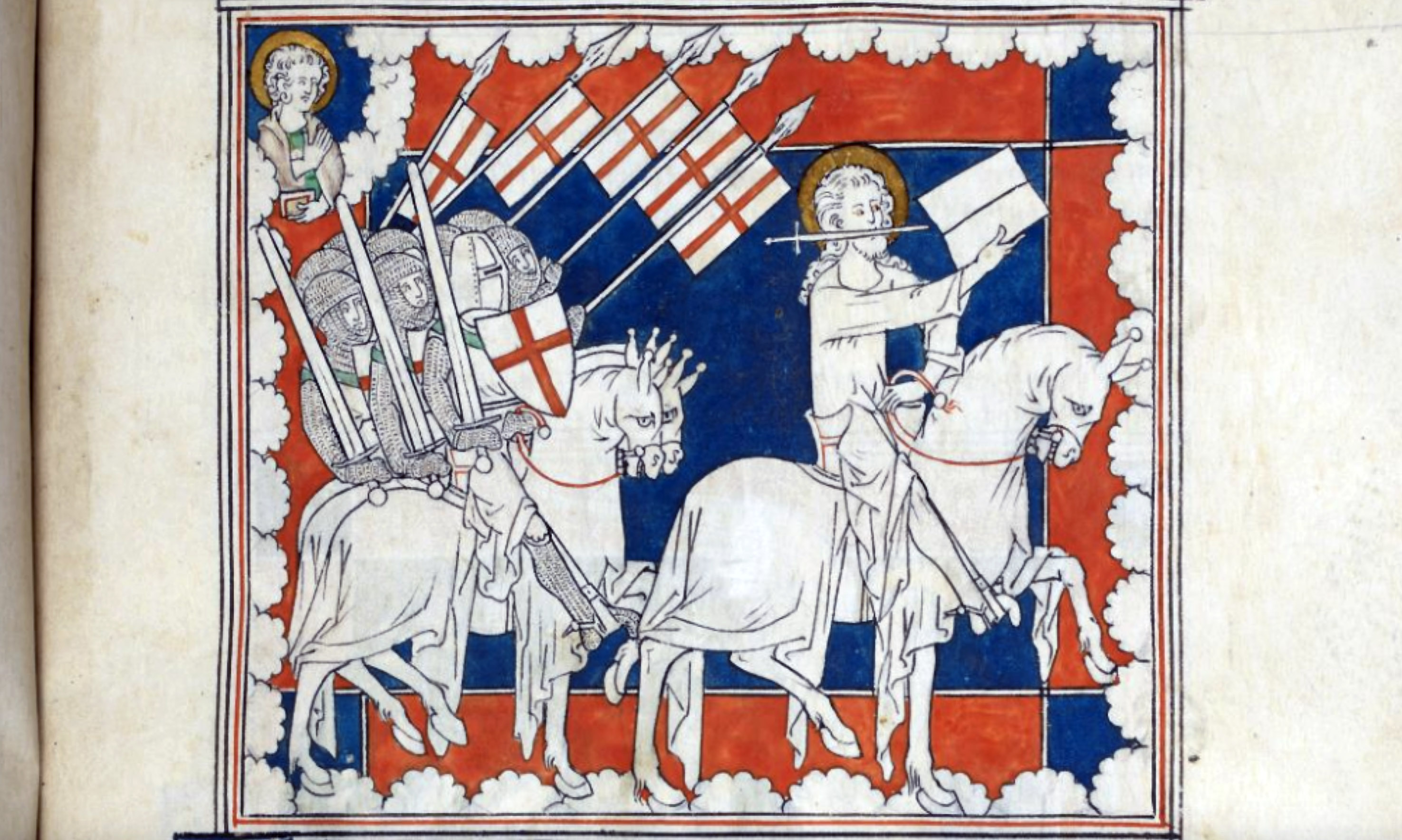

Unlike nearly any other place, the Holy Land (encompassing the city of Jerusalem and its environs), has continuously ignited the passions of the followers of the three monotheistic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Its sacred landscape, encompassing the former ancient Jewish Temple, the shrines associated with Jesus’ life, and the site of the Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey (isra) and Ascension (mi’raj), among many others, created an exceptional atmosphere of holiness. Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, western European Christians undertook a series of crusades (military expeditions) with the hope of recovering the Holy Land from Muslim hands. Believing that their actions were divinely sanctioned, an army of European Christians set off on crusade, with the indigenous Muslim, Christian, and Jewish populations that they encountered often suffering from their religious zeal. Armies of French European crusaders, or “Franks,” conquered Jerusalem and neighboring territories, established Crusader States, and asserted their leadership over the region and its diverse populations.

Map with the First through Fourth Crusades, from Atlas of the Middle East (Central Intelligence Agency, 1993)

Although the Holy Land was already profoundly multiethnic, the period of the Crusades (1095–1291), alongside ongoing trade, diplomatic exchange, migration, and pilgrimage, enriched this contact. It fostered close encounters between Europeans and Middle Easterners on the battlefield, in the marketplace, and in artists’ workshops. As a result, the art produced in the Crusader States reflects a complex engagement among western European visual traditions, the long artistic heritage of the Holy Land, and the arts of the Mediterranean (itself a dialogue between visual languages of various Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities). This chapter explores how crusading—as both a militant action and a powerful desire to restore the Holy Land to Christian sovereignty—had a profound impact on medieval visual culture.

A brief history of the Crusades

Western Wall (on the right) and the Temple Mount above with the Dome of the Rock in background, Jerusalem (photo: askii, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In 1095, Pope Urban II delivered an inflammatory sermon—he described how Muslims had desecrated the Lord’s sanctuary in Jerusalem by erecting images of their gods in the Temple Mount’s Dome of the Rock, which he called the Templum Domini, or Temple of the Lord. By the eleventh century, many Christians believed (mistakenly) that the Dome of the Rock had been built by either the biblical King Solomon or by a Byzantine emperor, rather than by the Umayyad caliph ‘Abd al-Malik in the seventh century. For them, the Dome of the Rock was a Christian building, and Jerusalem was a Christian city that needed to be liberated. They wanted access to the shrines associated with the life and ministry of Jesus, above all Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher, said to contain the sites of Jesus’ crucifixion, entombment, and resurrection. Promised absolution for their sins and eternal glory, the Franks embarked on a mission to reclaim the Holy Land. On July 15, 1099, the city of Jerusalem fell to the crusader army.

Map of Crusader States (underlying map © Google)

By the end of that year the crusading enterprise was truly Mediterranean-wide in scope. The crusaders established four Latin Christian states in the Eastern Mediterranean—the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Tripoli, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Edessa. When they lost the city of Jerusalem in 1187 to the Muslim Ayyubids, they established a Second Kingdom of Jerusalem based in the city of Acre. The crusaders turned to other fronts as well, conquering Cyprus from the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire and embarking further on the reconquest of Spain and Portugal. Although crusading fervor persisted throughout the thirteenth century and beyond, Jerusalem remained under Muslim control—with the exception of a brief period (1229–44) following the sixth crusade—until the early twentieth century.

As a primer to this chapter, the following essays provide a nuanced discussion of the complex history of the Crusades.

Read essays and watch a video about the history of the Crusades

/5 Completed

Transforming the Temple Mount

Al-Aqsa Mosque, Temple Mount, Jerusalem (photo: Andrew. Shiva, CC BY-SA 4.0)

As the crusader army established their presence in the region after their conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, they not only built fortified castles to protect their newly conquered territories, but also erected churches to transform the sacred landscape. Much of their attention was concentrated in the city of Jerusalem itself. On the Temple Mount, they converted the Al-Aqsa mosque, which they called the Templum Salomonis, or Temple of Solomon, into a palace and stables, and claimed the Dome of the Rock as one of the preeminent churches of the Kingdom. Surmounting its dome, they placed a gilded cross.

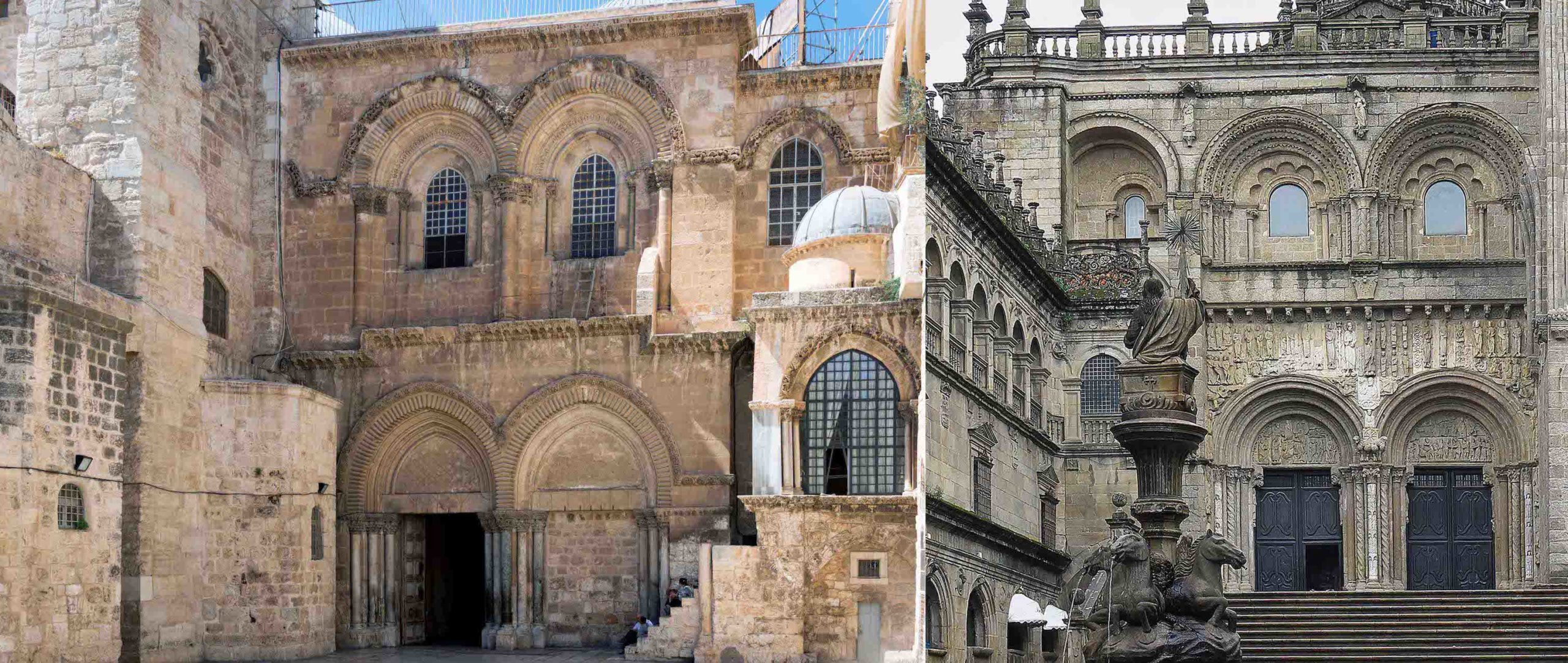

Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with blue domes, Jerusalem (photo: Berthold Werner, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher, housing the believed tomb of Christ, was the premier pilgrimage site of their new Kingdom. First built under Roman Emperor Constantine the Great in the fourth century, and restored by Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachos in the mid-eleventh century, the Church was already a well-established and complex architectural site. The crusaders modified the building anew, interjecting architectural elements commonly found in Romanesque pilgrimage churches into the preexisting framework of the church.

Left: Façade of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem (photo: xiquinhosilva, CC BY 2.0); right: La Puerta de las Platerías, Santiago de Compostela, 11th–12th century (José Luis Filpo Cabana, CC BY 3.0)

For example, for the façade they constructed new double portals, reminiscent of those at the pilgrimage church of Santiago de Compostela in Spain (one of the primary destinations for Christian pilgrims outside of the Holy Land). They adorned the façade with motifs from multiple sources, including reused Roman columns and Byzantine slabs, imitations of Late Antique and local Jerusalem sculpture, Romanesque figural sculpture, and Islamicizing arches. The façade’s eclectic appearance was as diverse as the communities of the city itself.

Seal of John of Brienne, King of Second Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (r. 1210–25), with representations of the Templum Domini, Tower of David, and Anastasis Rotunda (photo: momo, CC BY 2.0)

The Holy Sepulcher, along with the Templum Domini, came to signify the Christian kingdom in Jerusalem. For example, King John of Brienne, who ruled during the Second Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, represented the territories of his rule on his seal using the iconic imagery of the Templum Domini, the Anastasis Rotunda (the domed space over Jesus’ believed burial site in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher), and the Tower of David, where the biblical king David was believed to have composed the psalms.

Read essays about transforming the Temple Mount

Dome of the Rock: Called the Templum Domini by the crusaders, the Dome of the Rock was in fact built under the Umayyad Dynasty.

Read Now >

Pilgrimage routes and the cult of the relic: Romanesque architects modified the architecture of pilgrimage churches to ease and enhance the viewing of sacred relics.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Artistic interaction in the Holy Land

As in the façade of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, other works of art and architecture produced in the Holy Land throughout the eleventh through thirteenth centuries exemplify the remarkable contact and artistic exchange of the crusader period. Visually eclectic, they exhibit elements of western medieval, Byzantine, and Islamic visual traditions simultaneously.

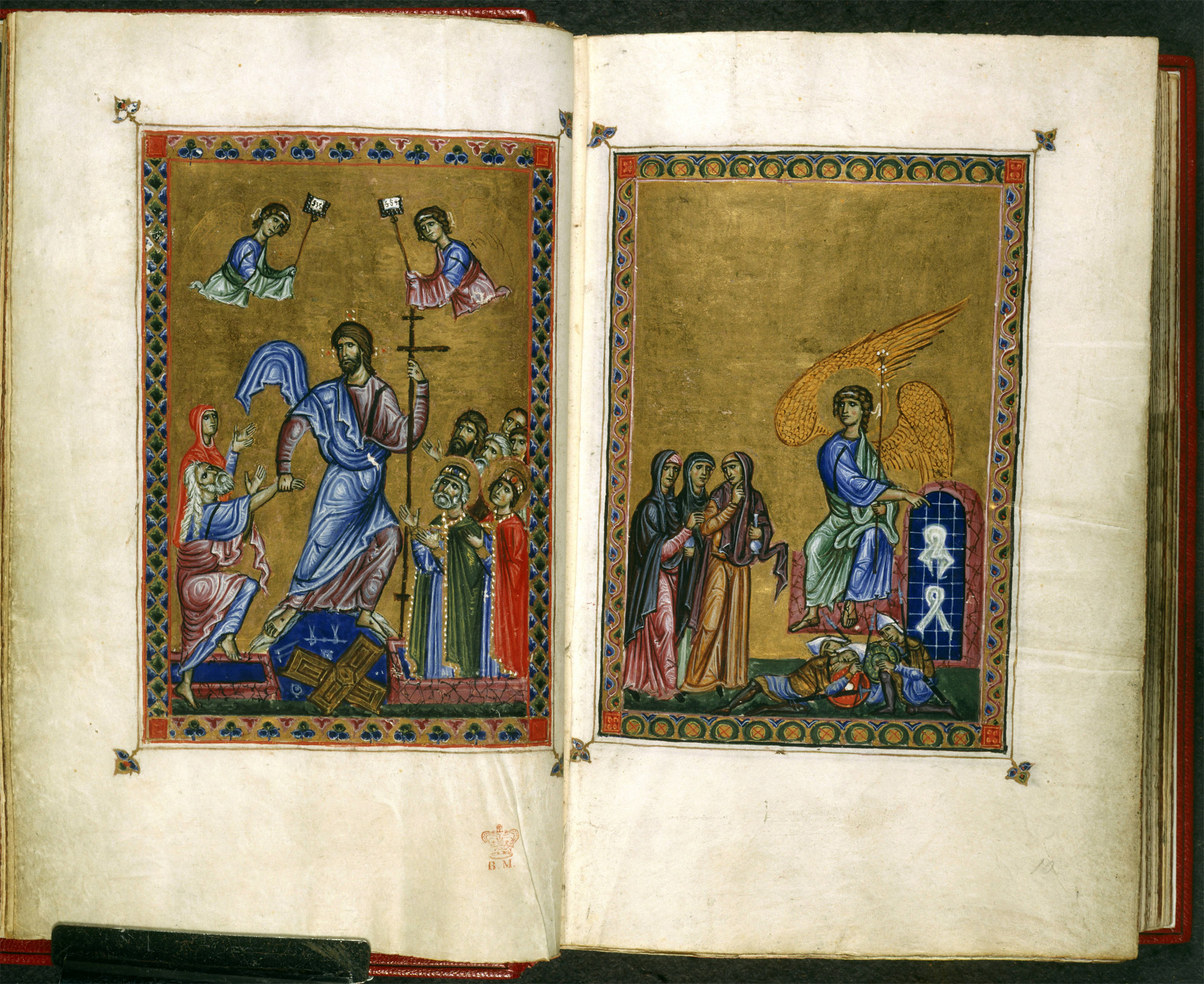

The Melisende Psalter (Egerton 1139, 9v and 10r), 1131-1143 (© The British Library)

The Melisende Psalter, for example, commissioned for Queen Melisende of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, drew on both Byzantine and Romanesque manuscript traditions. One of the manuscripts’ painters, Basilius, a Byzantine-trained artist of Western or Crusader origin painted twenty-four prefatory miniatures, a series of images intended to prepare the reader to engage with the text. Although the images themselves are primarily Byzantine in their iconography and style, such a cycle of images is a Western Christian invention. The manuscripts’ other three illuminators, likely all Western, introduced Romanesque figural decoration as well as geometric designs inspired by Islamic art.

A Crusader icon (left) and painting (right) from the Italian Peninsula showing an intimate scene of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. Left: Icon of the Virgin and Child, Hodegetria variant, 13th century, Byzantine or Crusader, made in Egypt, tempera on wood, 25.4 x 18.4 x 1.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna and Child, c. 1290–1300, tempera and gold on wood, 27.9 x 21 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Similarly, the Crusader icon of the Virgin (left) combines a Byzantine style of painting with a more intimate rendering of the Virgin and Child—likely drawing from European artistic traditions in which the Virgin gazes at her infant son. The icon may have been produced at the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, Egypt, a sixth-century Byzantine monastery which attracted Jewish, Christian, and Muslim pilgrims as the believed biblical site of Moses’ encounter with the burning bush, described in the Hebrew Bible. In the eleventh through thirteenth centuries, with an increased crusader presence in the Sinai region (the northeastern extremity of Egypt), the Monastery’s religious and institutional significance attracted new waves of Latin Christian visitors. The Monastery became an important site of contact for Byzantine, Latin, and local artists and pilgrims, and may have even housed painters of crusader origins.

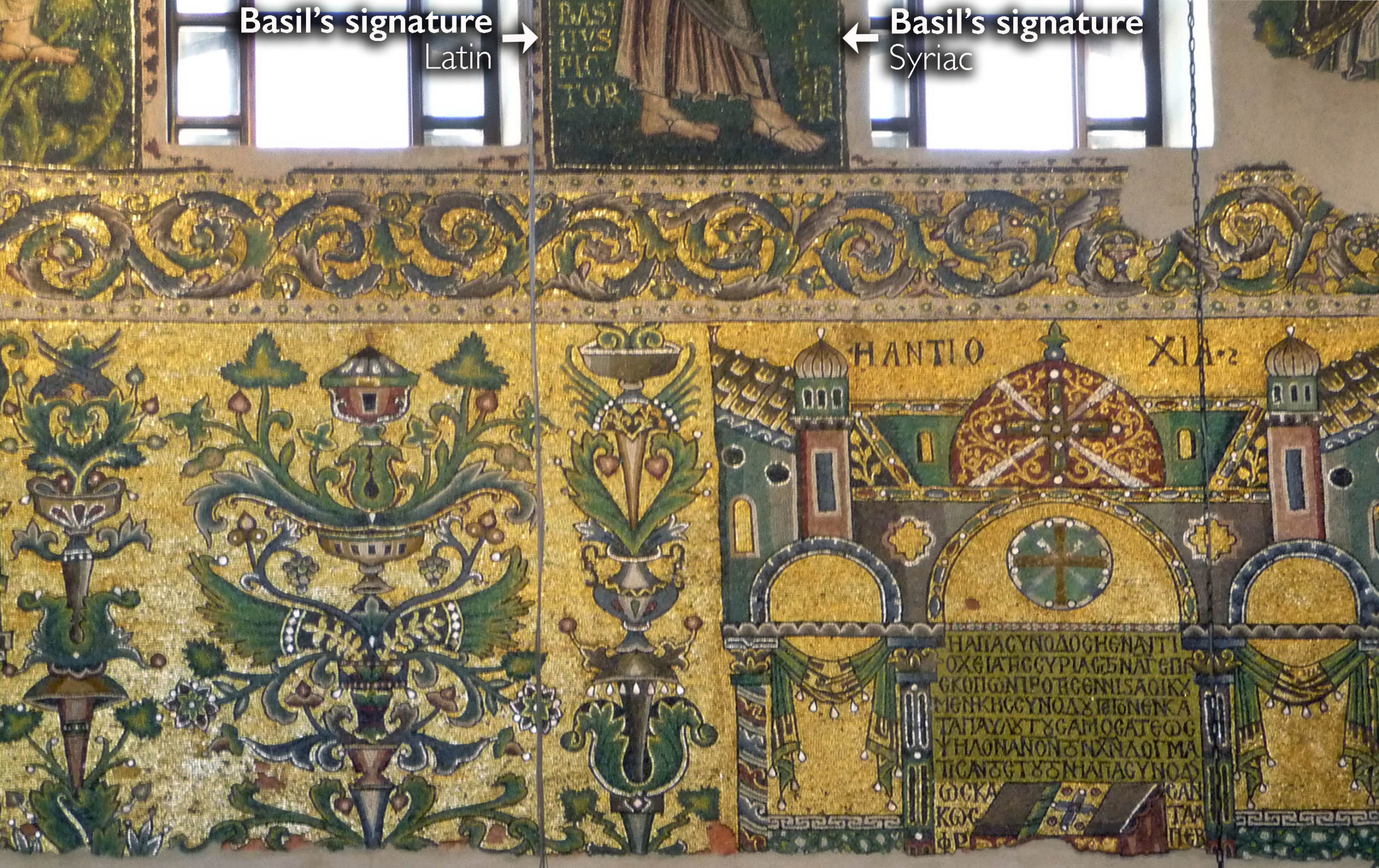

Mosaics of Church councils and Basil’s signature, Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem (photo: Immanuel Giel, CC BY-SA 4.)

Perhaps one of the best examples of this artistic interaction can be seen in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, first built under Emperor Constantine in the fourth century. Between 1167–69, Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, King Almaric I of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and Raoul, the Latin Bishop of Bethlehem, jointly sponsored the restoration of the church. Although cross-confessional patronage of churches and devotional media became increasingly common during the period of the Crusades, this joint venture stands out for its scale and the importance of its patrons. Their names, along with the name of the designer of the mosaics, a Master Ephraim, are mentioned in Greek and Latin inscriptions, the languages of the two most prominent communities of the Kingdom. Along with their shared patronage, the church’s mosaic decoration (including imagery of the life of Christ and images of church councils between the Latin and Greek churches), also reflects a combination of local and foreign artistic traditions.

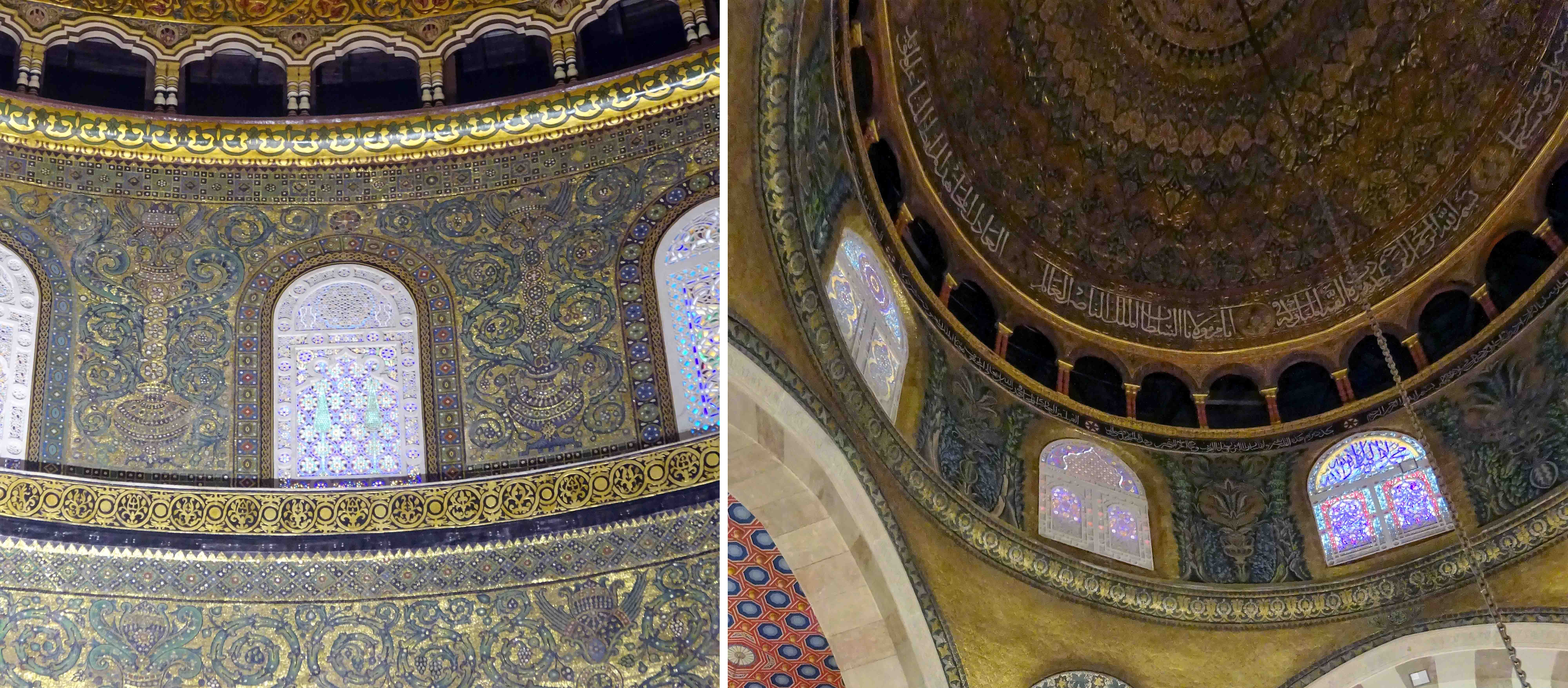

Left: Interior view of the Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra), Umayyad, mosaics, 691–92, with multiple renovations, patron Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik, Jerusalem (photo: Virtutepetens, CC BY-SA 4.0); right: Mosaics around the dome’s drum, 11th century, Al-Aqsa Mosque, Temple Mount, Jerusalem (photo: Virtutepetens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The mosaics themselves show similarities both with contemporary Byzantine mosaics and manuscript painting as well as with the Umayyad mosaics then visible in Jerusalem, including the seventh-century mosaics of the Dome of the Rock and the eleventh-century mosaics in the al-Aqsa mosque. Moreover, an Arab-Christian mosaicist named Basil signed his name in both Latin and Syriac, confirming the involvement of local artisans in the church’s decoration.

Paintings of saints on the columns in the nave, Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem (photo: Bukvoed, CC BY 4.0)

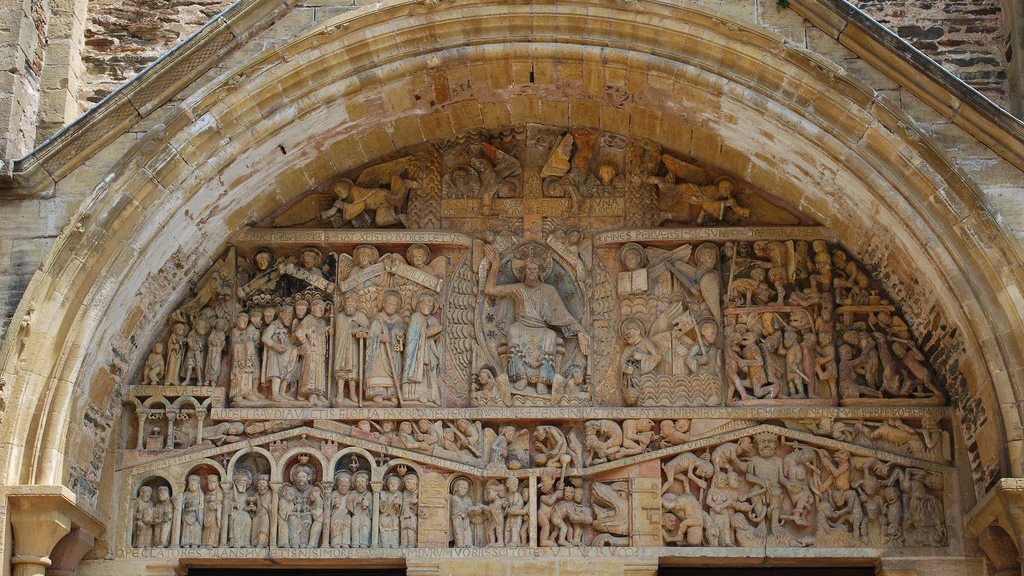

In addition to the mosaic program, the painted columns of the Church of the Nativity’s nave feature saints worshiped in different parts of the medieval world, reflecting the international origins of the church’s medieval pilgrims and sponsors—from Saint Olav of Norway for a Norwegian donor, to Saint Theodosius for the sake of a Greek visitor, to Saint James the Great for two western pilgrims who had previously visited the Church of Santiago de Compostela. Finally, bilingual graffiti, including the Arabic names of two eleventh- or twelfth-century Muslim pilgrims, testifies to the cross-confessional importance of the holy site.

Read essays about artistic interaction in the Holy Land

Melisende Psalter: The combination of Eastern and Western styles in this royal manuscript likely originated in a Crusader workshop in Jerusalem.

Read Now >

Art and architecture of Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai: The Monastery of Saint Catherine houses a remarkable collection of Byzantine manuscripts and icons, including several which reflect the cross-cultural interaction of the crusader period.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Going on Crusade

Whether spurred by religious zeal and the desire to reconquer the Holy Land, following in the footsteps of their relatives who had already gone on crusade, or merely eager to travel beyond the confines of their own cities, crusaders embarked on arduous journeys that exposed them to new peoples, languages, cultures, and landscapes.

Left: A Knight of the d’Aluye Family, after 1248–by 1267, French, limestone, made in the Loire Valley, France, 33 × 85.1 × 212.1 cm, 543 kg (The Cloisters); right: detail of the sword’s hilt

A member of the d’Aluye family, a three-generation French crusading family, commissioned a tomb effigy depicting the deceased as a young, pious soldier. Resting his feet atop a lion and pressing his hands together in prayer, the warrior appears as a courageous crusader. Along with his suit of mail and shield, the warrior bears an unusual sword. Rather than a European-style sword, it corresponds to contemporaneous Chinese swords, suggesting that he might have acquired it during his travels as a crusader while away from home. Although we will never know exactly how the d’Aluye knight came into possession of the Chinese sword, it is a testament to the extensive contact between western Europe, West Asia, and East Asia, in part facilitated by the Silk Road, an ancient network of trade routes established in the second century B.C.E.

![[Image: Pilgrimage ampulla from Jerusalem with depictions of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (front) and two warrior saints (reverse)(British Museum)]](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/1613337106-1-copy.jpg)

Pilgrimage ampulla from Jerusalem with depictions of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (front) and two warrior saints (reverse), 12–13th century, lead, made in Jerusalem, 56.6 x 37 mm (British Museum)]

Prior to their return, crusaders, as well as pilgrims, often collected souvenirs from the Holy Land as mementos of their journeys. Whether organic materials, such as dirt, stones, and oil, made holy through proximity to a holy site, or man-made objects, souvenirs were powerful reminders of the physical and spiritual experiences of a pilgrim’s or crusader’s travels. Moreover, the mass-production of memorabilia functioned as crusader propaganda, spreading a message of the Christian Jerusalem that owed its existence to the conquests of the Crusades

In the Aftermath . . .

In 1187, Salah al-Din defeated the Crusaders and reasserted Muslim control over Jerusalem. He promptly reconsecrated Jerusalem’s Haram al-Sharif, or Temple Mount, and its holy sites, including the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque, for Muslim worship. In celebration of the decisive conquest, he ordered the transfer and installation of a wooden minbar, or pulpit, from Aleppo, Syria, in the Mosque of al-Aqsa.

Nur al-Din minbar, al-Aqsa mosque, photograph taken between 1934-39 prior to the tragic destruction of the minbar by arson in 1969 (Library of Congress)

In the decades following Jerusalem’s recapture, the Ayyubids reconstructed the Holy City, clearing the substantial crusader architecture that had accumulated over eighty years of crusader presence. Rather than destroying these materials, the Ayyubids reused them in the construction and decoration of their own monuments. They likely used the building materials from crusader architecture as spolia, for pragmatic, aesthetic, and symbolic reasons. On the one hand, they offered useful raw material for constructing new monuments. At the same time, their purposeful reuse suggests that they could have been seen as a statement of triumph over their crusader enemies. However, the Ayyubid’s widespread reuse of spolia from many different periods and regions, including ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman, Byzantine, and Crusader, indicates their aesthetic preference for a combination of diverse visual languages.

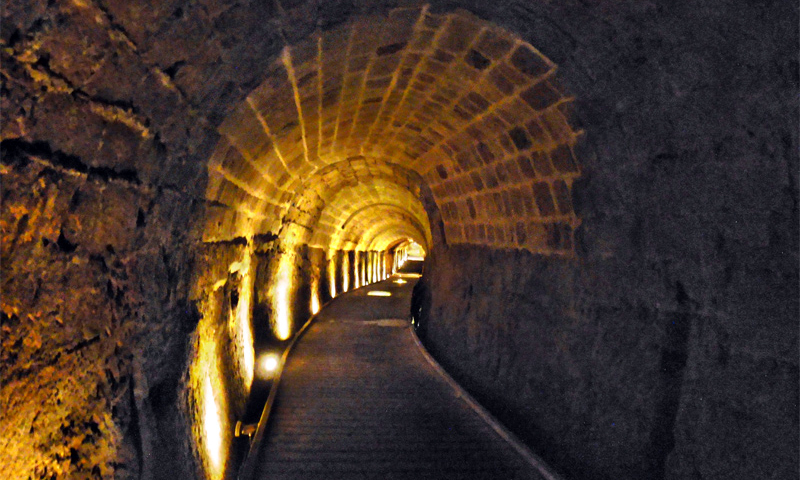

Well of Souls, Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem (photo: Lazhar Neftien, CC BY 2.0)

In the Dome of the Rock, for example, the portal to the Well of Souls (a cave beneath the rock), is adorned with a combination of crusader spolia, including crusader capitals and fragments with acanthus leaf, or vegetal decoration.

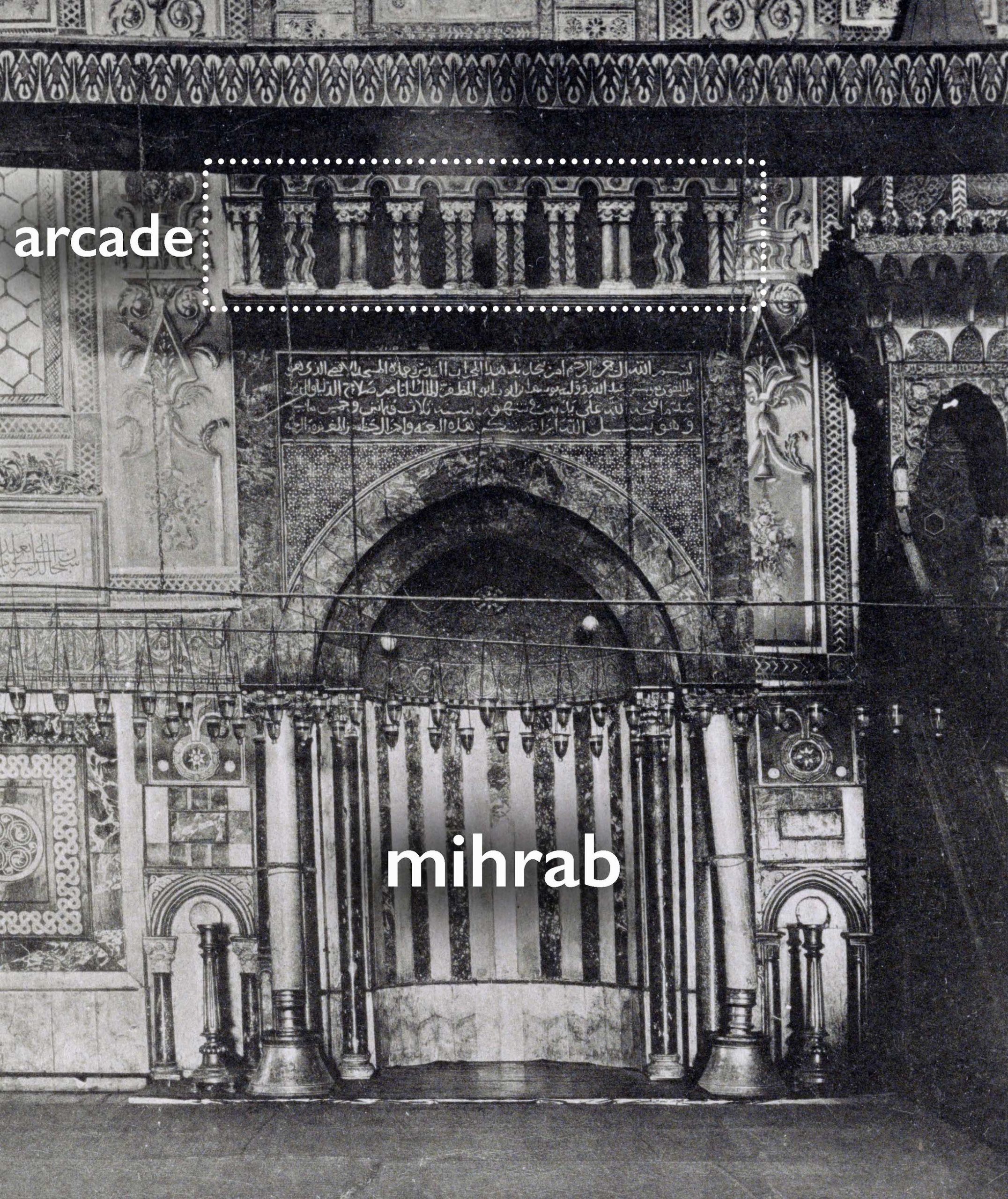

Mihrab and arcade above it, Al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem, photograph published as plate 9 in Bilder aus Palästina. Nord-Arabien und dem Sinai (Berlin: Dietrich Riemer, 1916) (Library of Congress)

In the al-Aqsa mosque, crusader spolia is especially concentrated around the mosque’s mihrabs. The central mihrab was redecorated in 1187 following the recapture of Jerusalem, so it is likely that this accumulation of crusader ornament was a conscious aesthetic and symbolic choice. Crusader columns and foliate capitals are set within and on either side of the central mihrab, while a crusader arcade of alternating miniature straight and zig-zag spiral columns is positioned above.

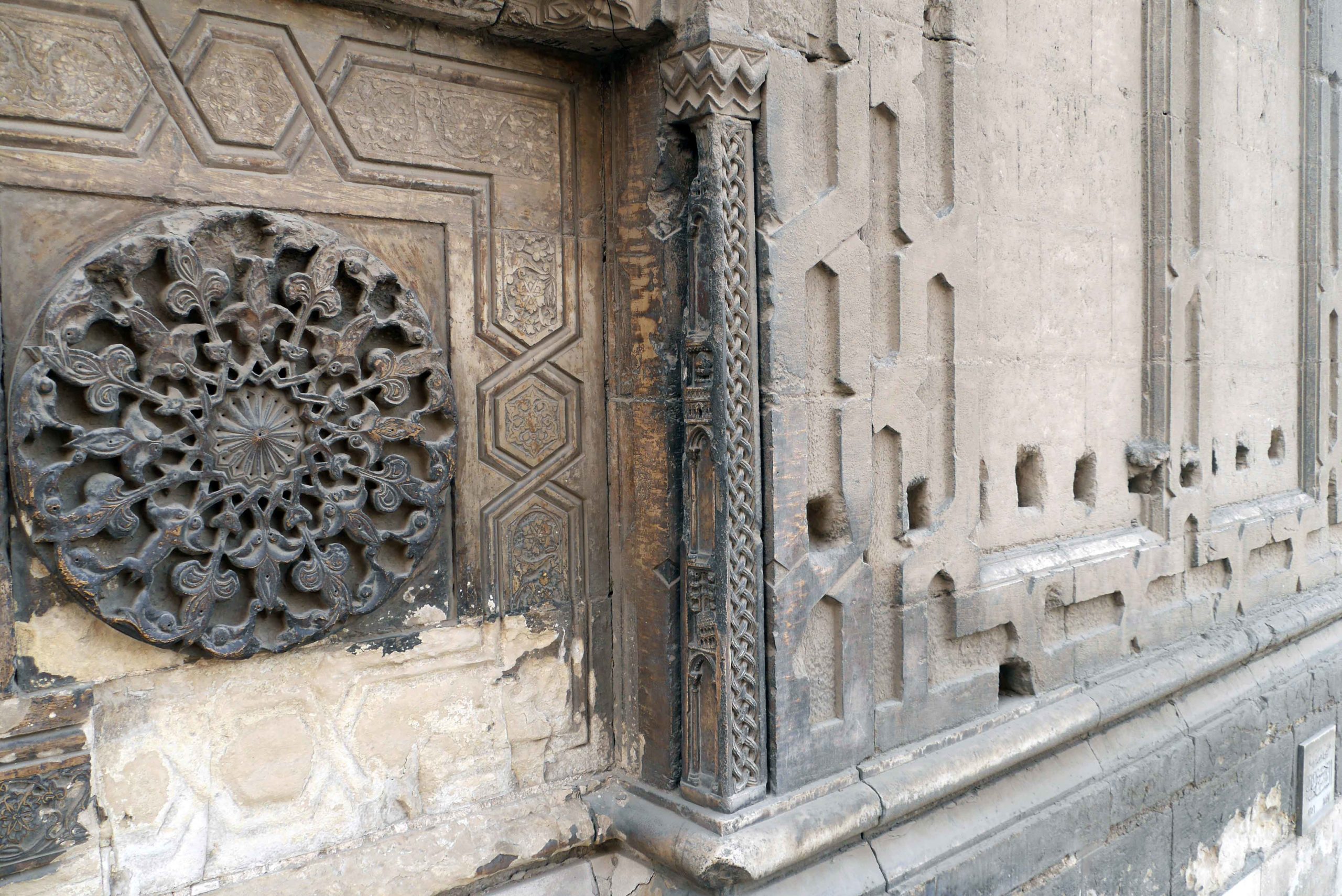

Lintel on the right side of the main entrance of the madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Katherine Werwie, CC BY 2.0)

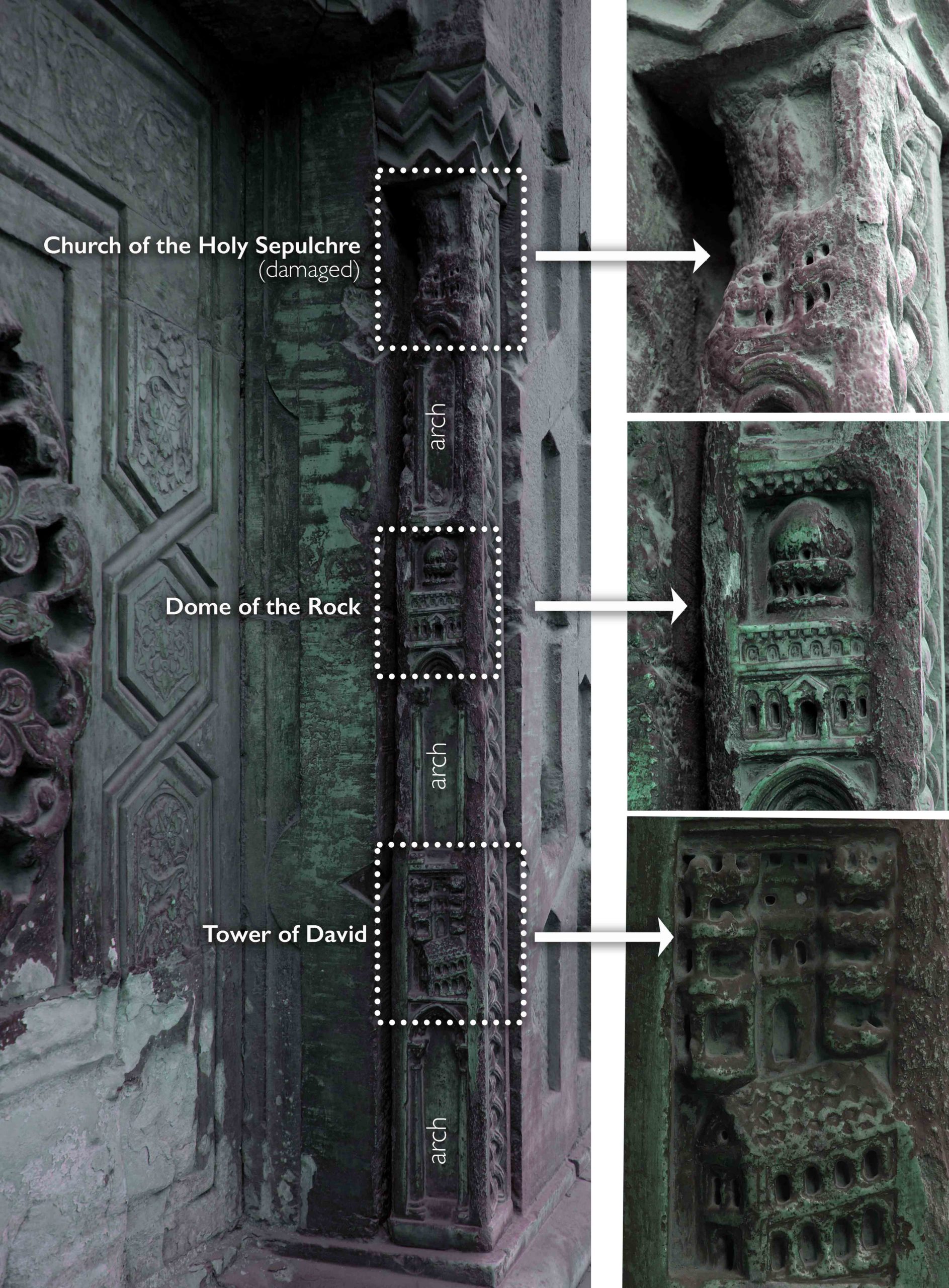

Crusader spolia was also found outside of Jerusalem in other Muslim controlled territories, including in thirteenth-century Ayyubid Syria and Egypt, as well as later in fourteenth-century Mamluk Egypt. In Cairo, for example, the Complex of Sultan Hasan incorporates several examples of crusader sculpture, including two prominent pilasters flanking its monumental portal.

Pilaster on the right side of the main entrance, showing the the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Templum Domini (Dome of the Rock), and the Tower of David. Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, 1356–1363/758–764 AH, Cairo, Egypt (photo: Katherine Werwie, CC BY 2.0)

One pilaster features floral ornament while the other includes representations of three Jerusalem monuments—the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Templum Domini, and the Tower of David. By this time, Jerusalem had long been under Muslim control; however, the reused pilaster referenced the former rule of the Holy Land by Christian Europeans as well as marked the current Mamluk sovereignty over the region. Positioned in the entry to the complex and visible to all who entered, it could have asserted Sultan Hasan’s authority as ruler by visually reminding the viewer of the geographic expanse of his reign, stretching all the way to Jerusalem.

Read an essay about the aftermath of the Crusades

Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan Cairo: Along with the pilasters, crusader capitals are incorporated into the mihrab of the Mosque of Sultan Hasan.

Read Now >/1 Completed

When Crusades go sideways: Byzantium and the Fourth Crusade

Horses of San Marco (ancient Greek or Roman, likely Imperial Rome), 4th century B.C.E. to 4th century C.E., copper alloy, 235 x 250 cm each (Basilica of San Marco, Venice)

In 1203, a fourth group of crusaders set off for the Holy Land. However, their journey was instead diverted to Constantinople, the capital of the (Christian) Byzantine Empire, where they laid siege to the city. On April 13, 1204, the crusaders seized control, establishing the Latin Empire of Constantinople under Latin King Baldwin II (1204–61). Although far from the original intent of the crusaders, the sack of Constantinople had a profound impact on the political and artistic future of the Byzantine Empire and on Western Europe. Devastated and displaced from Constantinople, the Byzantine Empire was fragmented into successor states—the Empire of Trebizond, the Empire of Nicaea, and the Despotate of Epirus—each trying to reestablish the Empire in exile. Thereafter, Byzantine art and architecture increasingly incorporated the local artistic traditions of these regions. Constantinople itself was plundered and depleted of its sacred treasures. The Byzantine Empire’s remarkable collection of Christian relics, along with masterpieces of Byzantine art—sacred icons, imperial crowns, golden enamels, reliquaries, and textiles—were dispersed across Western Europe, conferring prestige and power on western rulers and on the Latin Church.

Read essays about when Crusades go sideways

Byzantine art and the Fourth Crusade: Following the Sack of 1204, Constantinople’s treasures found new homes across Western Europe.

Read Now >

Byzantine architecture and the Fourth Crusade: Byzantine architecture pursued new directions in the exiled Empires of Nicaea and Trebizond, and the Despotate of Epirus.

Read Now >

Constantinople’s bronze horses: the story of one Crusader trophy and its display in Venice.

Read Now >

Sainte-Chapelle: A monumental reliquary, built to house King Louis IX’s collection of Byzantine relics acquired after the Sack of 1204.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Although the Crusader States finally collapsed with the fall of Tripoli in 1289 and Acre in 1291, the networks of Mediterranean exchange created by the crusader presence in the Holy Land continued to thrive well beyond the thirteenth century. Works of art produced in the East had now become fashionable in European markets, demanding an ongoing presence of European merchants in the region.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did the complexities of cultural contact during the Crusades—whether through exchange or conquest—shape the art of this period?

How did art and architecture function as a tool to remember and reimagine the religious and crusader experience in the Holy Land?

What role did architectural and artistic reuse play during and in the aftermath of the Crusades?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did the complexities of cultural contact during the Crusades—whether through exchange or conquest—shape the art of this period?

How did art and architecture function as a tool to remember and reimagine the religious and crusader experience in the Holy Land?

What role did architectural and artistic reuse play during and in the aftermath of the Crusades?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Ampulla (pl. ampullae)

Arab-Christian

Cross-confessional

Crusader states

Mihrab

Pilaster

Pilgrim

Psalter

Relic

Spolia

Tomb effigy

Learn more

Barbara Boehm and Melanie Holcomb. Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016).

The Crusader Bible, Online Exhibition, The Morgan Library and Museum

Cathleen A. Fleck, “Crusader Spolia in Medieval Cairo. The Portal of the Complex of Sultan Hasan,” Journal of Transcultural Medieval Studies, vol. 1, issue 2 (2014)

Finbar Barry Flood, “An Ambiguous Aesthetic. Crusader ‘Spolia’ in Ayyubid Jerusalem,” in Ayyubid Jerusalem. The Holy City in Context, 1187-1250, ed. By R. Hillenbrand and Sylvia Auld (London, 2009), pp. 202-215.

The Crusades (1095-1291), Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art