Mesoamerica: an introduction to what we mean by “Mesoamerica.”

Read Now >Chapter 23

Mesoamerica 200–900 C.E.

Map of Mesoamerica (underlying map © Google)

Between 200 and 900 C.E., a span of time known as the Classic period, a variety of cultures flourished in the diverse landscapes of Mesoamerica, a region that stretches from Central Mexico to northern Costa Rica. In this area, ancient cultures shared features like maize cultivation, the calendar, and ballgames. At centers throughout Mesoamerica, artists created monumental works of art and architecture, often commissioned by powerful rulers, that expressed ideas about the world around them and connected the everyday world with the sacred.

Pyramid of the Moon, completed c. 200 C.E., at the top of the Avenue of the Dead, Teotihuacan, Mexico (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While Mesoamerican cultures shared some features, they were also incredibly diverse. In Central Mexico, the metropolis of Teotihuacan was an enormous city with larger-than-life architecture and widespread political power. On the Gulf Coast of Veracruz, artists created works related to the ballgame and ritual power, while in the Maya area, hieroglyphic writing helps to flesh out the political and religious content produced by artists in a region dominated by competing city states.

El Tajin Ball Court, c. 800–1200 C.E., Classic Veracruz Culture (photo: Oscar Zorrilla Alonso, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The works of art and architecture featured in this chapter are predominantly stone and ceramic, but these represent just a fraction of the art that existed in this period. Sources attest to the creation of works of art in many media, from painted books to cotton textiles to jade jewelry.

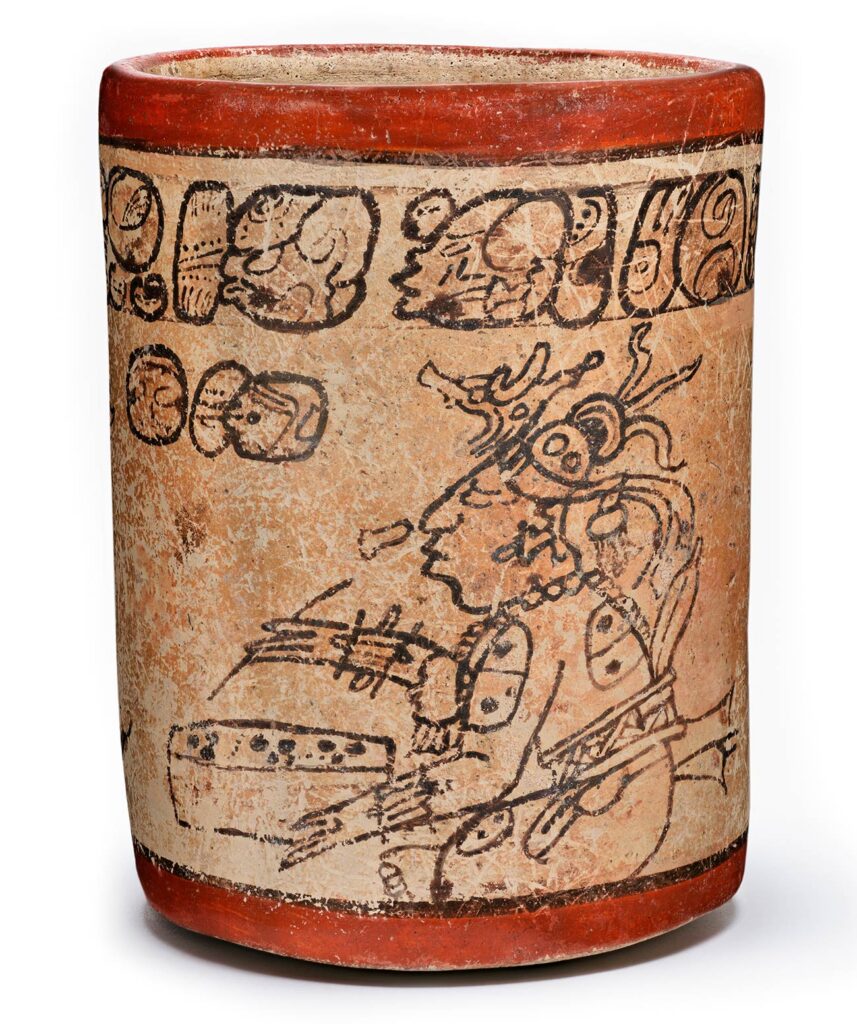

Codex-Style Cylinder Vessel with Scribes, 650–800, Guatemala or Mexico, Northern Petén or Southern Campeche, Maya, ceramic (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

This chapter addresses four themes in Mesoamerican art history:

- monumental architecture

- powerful rulers and dynamic politics

- connecting with the sacred

- and discerning everyday life.

As you explore this material, pay particular attention to both the similarities and differences between works. While many Mesoamerican cultures constructed step pyramids, for instance, imagery played different roles in these buildings from different cultures. And despite variation in style and content, Mesoamerican imagery addresses consistent questions:

- How did ancient architects construct buildings that expressed ideas about identity and the structure of the world?

- In what ways did rulers convey their power through art?

- How was art able to connect the human world with the sacred one, and what can art tell us about everyday life?

The following introductory essays explore what we mean by “Mesoamerica” and the labels scholars use for time periods in this region. They also consider some of the characteristics that cultures in Mesoamerica shared, including a calendar, and introduce two important groups: Teotihuacan and the Maya.

Watch videos and read essays about some Mesoamerican cultures

Teotihuacan: By the 6th century, Teotihuacan was the first large metropolis in the Americas.

Read Now >

The ancient Maya: United by belief systems, cultural practices that included a distinct architectural style, and a writing system.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Monumental architecture

Temple of the Inscriptions, Palenque, Maya (photo: Carlos Adampol Galindo, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Mesoamerican cultures from 200–900 C.E. constructed enormous monumental centers that served political, religious, and economic purposes. Architectural traditions in this time period grow out of earlier constructions in Mesoamerica, as explored in the chapter on early Mesoamerica. Buildings served many purposes in Mesoamerica—but whether constructed as royal tombs, temples to the gods, or for other uses, the architecture of Mesoamerica expressed fundamental ideas about powerful people and the structure of the universe. The buildings explored in this section would have been enlivened with colorful paint, smoke billowing from ceremonial incense burners, and the human actions happening in and around them.

Pyramid of the Sun, completed c. 100 C.E., on the Avenue of the Dead, Teotihuacan, Mexico (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Monumental architecture helps us understand what was important to ancient builders and audiences—but there are also significant gaps in our knowledge. The enormous city of Teotihuacan, for instance, was home to some of the largest buildings in the Americas, but archaeologists have not recovered royal graves or palaces, and the governmental structure of the city and surrounding communities remains unclear. At Palenque, in contrast, rulers and their families were interred inside buildings in the city center. Panels inside those structures presented information about politics and religion, allowing contemporary viewers to reconstruct detailed histories of the city.

Relief panel showing a ritual in the south ballcourt at El Tajín, Mexico (photo: Simon Burchell, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, artists adorned many structures at El Tajín with intricate low relief carvings that hint at the activities that may have occurred there. Throughout Mesoamerica, architecture reveals different information over space and time.

The following links will introduce you to important buildings at Teotihuacan, Palenque (Maya), and El Tajín (Veracruz), and the ways in which each building conveyed information about political might and religious power.

Watch videos and read an essay about monumental architecture

Pyramid of the Moon and Pyramid of the Sun, Teotihuacan: Two important pyramids on the city’s Avenue of the Dead.

Read Now >

Palenque: One of many Maya city-states, Palenque rose to prominence in the seventh century thanks to an ambitious local lord.

Read Now >

El Tajín: Intricate carvings decorate many of the buildings at the this important Gulf Coast city.

Read Now >/3 Completed

The Maya: Powerful Rulers, Dynamic Politics

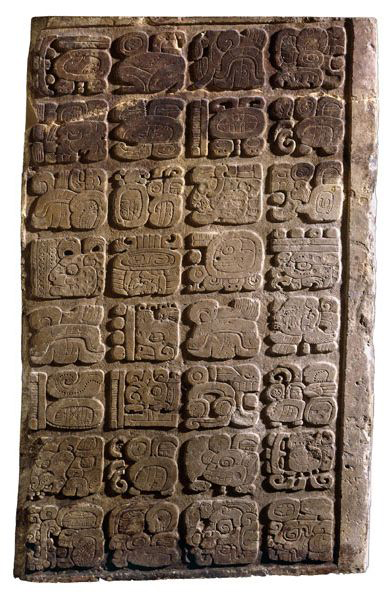

An example of Maya hieroglyphic writing. Yaxchilan lintel 35, Maya, Late Classic period (600–800), From Yaxchilán, Mexico

Although people throughout ancient Mesoamerica created writing systems, Maya hieroglyphic writing is the most thoroughly understood. Texts from the Classic period reveal a dynamic region in which various city-states vied for control over land and resources. Each polity was headed by a ruler (usually male, but sometimes female) who commissioned works of art that emphasized their military strength and ability to connect to the godly realm.

Chakalte’, Relief with Enthroned Ruler (lintel from La Pasadita, Guatemala), late 8th century (Classic Maya), limestone and paint, 88.9 x 87.6 x 7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

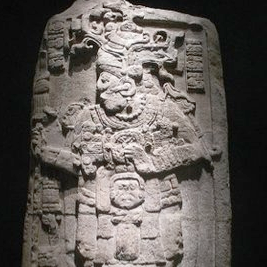

These works could take several forms. Stelae are large upright stones, smoothed into a door-like shape and carved in low relief on one or more sides. Lintels are stones that hang over the doorway, directly above your head as you walk through the door. These were usually carved in low relief. Both stelae and lintels would have been painted.

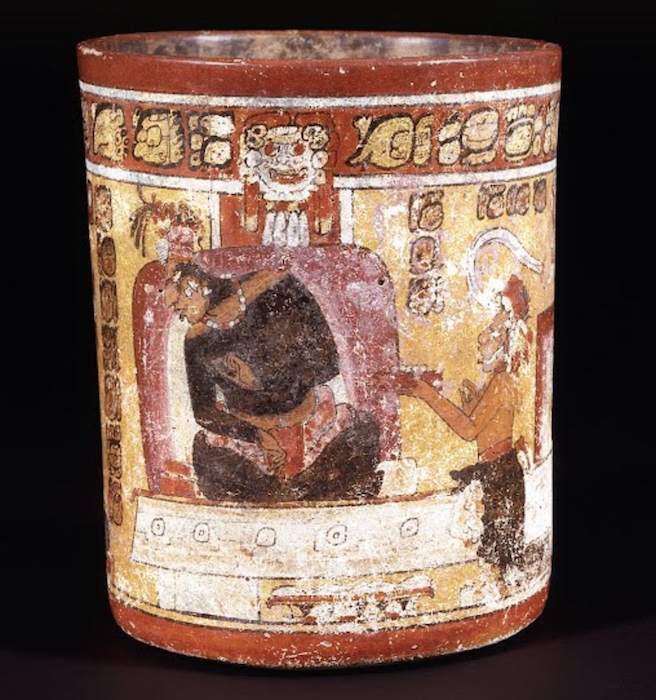

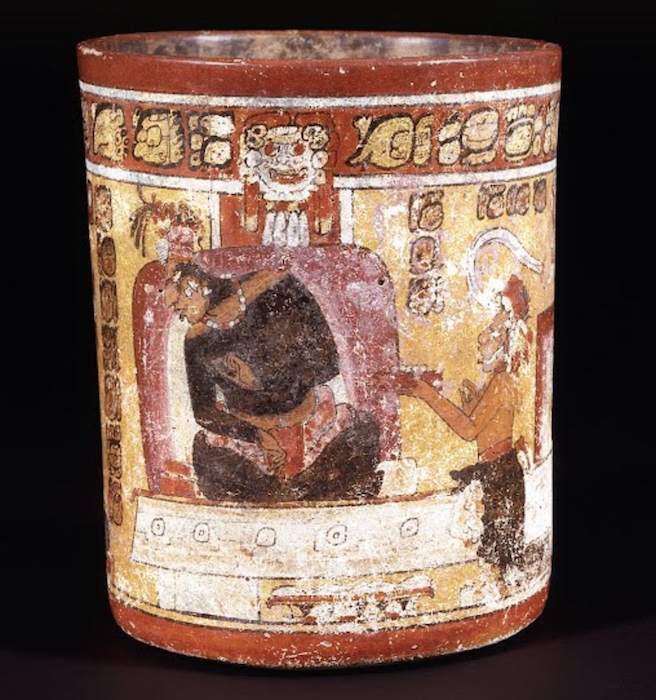

Painted Vessel (Enthroned Maya Lord and Attendants), c. 650–750 C.E., Maya, cylinder vase, ceramic, 16.51 x 20.32 cm (Dumbarton Oaks Museum)

Maya artists also created ceramic vessels and painted them with elaborate scenes and texts. Combined, these works of art present information about who ruled, and when—but also about the relationships between people, both violent and peaceful.

As you consider this material, remember that these are examples of art commissioned by the elite. Many works would have been seen only by the wealthy or powerful. The “Enthroned Ruler” lintel speaks to the relationship between rulers and their vassals—but it was placed in a doorway of an elite building and would have been difficult to stop and study. This Maya vessel, too, gives viewers a glimpse into the royal court with its depiction of a ruler interacting with attendants. Painted ceramic vessels were typically gifted among members of the elite; the size and detail of the painted vessel help us imagine its viewing in an intimate setting, held in the hands and rotated to see the complete image.

Stela 16, c. 711 C.E. (Classic Period), Tikal, Guatemala, 3.5 x 1.28 m (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Other works may have been seen by a wider swath of the population. Tikal Stela 16, with its depiction of a Tikal ruler in full ceremonial gear, is a good example. Although carved stone sculptures were generally commissioned by people of high status, ceramic figurines recovered from ancient houses indicate that works of art would have been part of the daily lives of Maya people.

Watch videos and read an essay about the Maya

Chakalte’, Relief with Enthroned Ruler: The power dynamic between ruler and vassals is on display here.

Read Now >

Politics and History on a Maya Vase: Over a thousand years before Instagram, Maya painted vases communicated about the lives of the rich and famous.

Read Now >

Tikal Stela 16: This stela a Maya royal portrait stela showing the ruler Jasaw Chan K’awiil bedecked in feathers, jade, and an elaborate headdress.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Connecting with the Sacred

Vessel with Mythological Scene, 7th–8th century, Guatemala, Mesoamerica, Maya, ceramic, 14 x 11.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Mesoamerican cultures shared beliefs about the animate power of the natural world, the ability of ancestors to interact with living people, and the ritual actions necessary to ensure the cooperation of otherworldly forces and the progression of time. The decipherment of hieroglyphic writing and a long history of excavation in the Maya area have made them a major source of information on Maya deities and belief systems. Ceramic vessels often showcase lively mythological scenes featuring gods, ancestors, and humans. The Maya vessel in this section, for instance, features the rain god, Chahk, and his role in the birth of another deity.

Lintel 25, Yaxchilán (Maya), after 709 C.E., Maya, Late Classic period, Structure 23, limestone, 109 x 78 x 6 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

Carved stone sculptures generally feature rulers in addition to gods. Communicating with otherworldly forces was a key source of power for Mesoamerican elites, and sculptures highlight the ability of kings and queens to interact with divine forces. This is the case on the lintels of Yaxchilán, which emphasize the role of Lady Xoc in conjuring a war deity.

Panoramic view of Monte Albán, Oaxaca, Mexico (photo: Eke, CC BY-SA 3.0)

While Mesoamerican cultures shared some beliefs related to the divine, we also see diversity. For example, at Monte Alban, a Zapotec site in Oaxaca that flourished between 200 and 600 C.E., a ceramic ancestor figure was probably placed in association with a tomb.

Ancestor figure, Zapotec, c. 200 B.C.E.–800 C.E., pottery, from Oaxaca, Mexico, 35 x 27 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Ancestors were important in Zapotec thought because of their ability to act on behalf of their descendants, and urns like this one may have held burned offerings like incense, blood, chocolate, and pulque, an alcoholic drink made from the maguey plant.

Watch a video and read essays about connecting with the sacred

Vessel with a mythological scene: The rain god, Chahk plays role in the birth of another deity.

Read Now >

Yaxchilán Lintels 24 and 25 from Structure 23: Lady Xoc plays an important role in communicating with the gods.

Read Now >

Ancestor figure, Zapotec: Offering vessels like this one have been found in the tombs of high-ranking Zapotec lords and noblewomen in the Oaxaca Valley in Mexico.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Discerning Everyday Life

Dog, Colima culture, c. 300 B.C.E.–300 C.E., slipped pottery, Mexico, from Colima, 36 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Many of the works in this chapter relate to gods and rulers—but other works of art hint at the daily life of ancient Mesoamerican people. A ceramic dog from the Colima culture of West Mexico was probably placed in a tomb. This object may represent the role of dogs as guardians for the dead on their way to the underworld. Such figures may also have been used as prompts in storytelling, and the dogs themselves were eaten at feasts.

Yoke, c. 1–900 C.E., Classic Veracruz culture, greenstone, 11.5 x 38 x 41.5 cm (American Museum of Natural History, Washington D.C.)

Elsewhere in Mesoamerica, artists created works related to the ballgame. Many cultures in Mesoamerica played ballgames using rubber balls. The games were social events, but also served political and ritual purposes. In Classic Veracruz, both ballcourts and low-relief representations of the game attest to its importance. Often called a “yoke,” this object is probably a ceremonial version of gear worn by ballplayers—and while it may have been placed in an elite tomb, it speaks to the role of games in political, religious, and social life of ancient Mesoamericans.

Mirror-Bearer, 6th century (Classic Maya), wood and red hematite, 35.9 x 22.9 x 22.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the Maya region, too, a rare wooden object provides a look at the people who made up Classic Maya courts. This work represents a kneeling figure who would have held a mirror for a Maya king. The stature and facial features of the figure indicate he is a dwarf. People of short stature were highly valued in Maya royal courts and played a number of roles. This figure is remarkable both because wood rarely survives in the humid lowlands of the Maya region, and because the detailing of his clothes hints at the rich textiles that would have been worn by ancient Maya people.

Watch videos and read an essay about discerning everyday life

Pottery dog, Colima culture: Dogs were believed to assist the dead in their journey to the Underworld.

Read Now >

The Mesoamerican ballgame and a Classic Veracruz yoke: Hundreds of courts survive for a ritual ballgame that united Mesoamerican society.

Read Now >

Mirror-Bearer, Maya: This fabulously-dressed mirror-bearer imitates the humans who performed this function in the royal courts.

Read Now >/3 Completed

The material traces that remain from Mesoamerica are incomplete: wood, textiles, and paper are among the many materials that artists worked with between 200 and 900 C.E. that have not survived the subsequent centuries. Yet the architecture, sculpture, and ceramics of Mesoamerican cultures offer compelling insights into the lives of ancient peoples. From connecting to the world of the gods, to negotiating political power, to commemorating feasts and ballgames, the art of Mesoamerica suggests diverse beliefs and practices that resonate with aspects of our lives today.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did ancient architects construct buildings that expressed ideas about identity and the structure of the world?

In what ways did rulers convey their power through art?

How was art able to connect the human world with the sacred one, and what can art tell us about everyday life?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did ancient architects construct buildings that expressed ideas about identity and the structure of the world?

In what ways did rulers convey their power through art?

How was art able to connect the human world with the sacred one, and what can art tell us about everyday life?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Mesoamerica

maize

ballgame

yoke

Maya hieroglyphs

lintel

stela

relief sculpture

Learn more

Read about Maya glyphs

Learn more about Mesoamerica on Mesolore

Watch a video about the Maya Popol Vuh