The Case for Land Art: What kind of an art can thrive with such a formidable co-star as Earth?

Read Now >Chapter 77

Re-Mapping Land Art: Earthworks, Borderlands, Ecology

Nicolás García Uriburu, Coloration of the Grand Canal, Venice, 1968, chromogenic print (Uriburu Foundation collection)

Introduction

Argentine artist Nicolás García Uriburu dyed the Grand Canal of Venice with a vibrant green pigment in 1968. Two years later, American artist Robert Smithson moved some six thousand tons of black basalt rocks into the form of a spiraling coil that juts out from the shore into the waters of the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, 1970, Rozel Point, Great Salt Lake, Utah (photograph taken June 2016)

Both of these works exemplify the radical genre of Land Art—art made in or of the natural environment—which was one among the eclectic array of new artistic practices that emerged in the mid-to-late twentieth century.

The critic Rosalind Krauss had Smithson’s Spiral Jetty in mind, among others, when she observed in 1979 that:

Over the last ten years rather surprising things have come to be called sculpture. Rosalind Krauss [1]

Krauss referred to some of these new works as “marked sites,” a term that describes an artists’ physical manipulation of a given place so as to create art out of the land itself. However, land is not just a neutral resource, or a blank canvas on which artists simply assert their creative vision. Like a palimpsest, landscapes contain traces of the many historical, cultural, ecological, and personal associations that can give a place a sense of deeper meaning. The desert landscape of the Southwestern United States, for instance, was central to the American Land Art movement of the late 1960s and 70s: artists perceived this region as “remote,” as if empty of human civilization. However, such landscapes have more recently been activated by artists to draw our attention to local Indigenous histories, methods of representing nature that differ from that of the European tradition, or the larger social impacts of the political borders that have been cut across the landscape. In addition, contemporary artists working with landscape imagery often do so to explore matters of ecological concern and worldwide perspectives on climate change.

This chapter takes an expansive view on the relationship of art, landscape, and nature in the late twentieth century. It asks: How have artists engaged with, represented, and re-mapped the physical environment in ways that are both critical and symbolic of humanity’s complex relationship to the earth? How have these landscapes been “occupied” both in society and in art? How can artists help us to understand hidden or marginalized histories of place, and compel us to be more respectful of the natural, political, and social ecosystems that we inhabit?

Nancy Holt, Sun Tunnels, 1973–76, concrete, steel, earth, Great Basin Desert, Utah, overall dimensions: 9 ft. 2-1/2 in. x 86 ft. x 53 ft. (2.8 x 26.2 x 16.2 m); length on the diagonal: 86 ft. (26.2 m) (Collection Dia Art Foundation with support from Holt/Smithson Foundation)

Land Art and American Landscape

Artists in the late 1960s and 1970s were drawn to the Southwestern United States, creating monumental earthworks that were carved and constructed across that region’s vast landscapes. American artist Nancy Holt, for instance, placed four concrete cylinders in a cruciform formation in the Great Basin Desert of Northwestern Utah. The cylinders are punctured with holes that align with the movement of constellations across the night sky, revealing connections between the individual body, the earth’s geology, and the vast scale of the cosmos.

Michael Heizer, Double Negative, 1969, Moapa Valley on Mormon Mesa near Overton, Nevada (MOCA)

Michael Heizer chose not to add elements to nature but rather to subtract: To make his work Double Negative, in 1969, he removed over 200,000 tons of sandstone from Mormon Mesa in Nevada, creating two massive cuts in the earth.

Just like their peers in other 1960s genres, Land artists wanted to bring their work outside of traditional galleries and museums, and to embed art in “real” places and environments. (Despite this critique, institutional support has been key to the production and ongoing maintenance of earthworks). Smithson and his peers were not only responding to their contemporary world, however: They were fascinated with pre-modern, ancient, and non-Western earthworks, from the Pyramids of Giza and the Nazca Lines of Peru to the Great Serpent Mounds of Ohio. While seeking to radically expand the definition of art, Land artists wanted to return a sense of monumentality and site-specificity to contemporary art in ways that had not been demonstrated in hundreds of years, since the ages of soaring Gothic cathedrals, ancient amphitheaters and stelae.

Essays and ideas about Land Art and American landscape

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty: Drought and rain govern when this work of art in Utah’s Great Salt Lake can be seen.

Read Now >

Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field: 400 stainless steel poles in the high desert of New Mexico are the object, but the subject is the sublime.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Borderlands and Occupations

Julie Mehretu, HOWL, eon (I, II), 2016–17, ink and acrylic on canvas, each 823 x 975.4 cm (SFMOMA)

In her commissioned pair of wall paintings for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, entitled “HOWL, eon (I, II)” (2017), contemporary artist Julie Mehretu explains that:

There is no such thing as just landscape.Julie Mehretu [2]

Her monumental murals, which condense multiple layers of intersecting and abstracted images, reference the histories of colonialism and occupation that have unfolded across the American landscape, from Manifest Destiny and the displacement of Indigenous societies to abolitionist movements and contemporary protests that have re-claimed public space, such as those associated with the Black Lives Matter movement. Acknowledging the complex politics of landscape and history, this section includes art works that reflect on the numerous ways that the natural environment has been politically or institutionally “occupied.”

The interdisciplinary collective Postcommodity creates site-specific installations and interventions that critically examine our modern-day institutions and systems through the history and perspectives of Indigenous people. Cristóbal Martínez, Kade L. Twist, and Raven Chacon, “Repellent Fence,” 2015, two-mile-long line of enormous balloons across the Arizona-Sonora border

Many of the works below are specifically attentive to borderlands—the regions across or through which geo-political borders have been imposed. These are sites of division and displacement, but also exchange, encounter, and creative fusion. Artists, including Tanya Aguiñiga and the collective Postcommodity, have engaged with the U.S.-Mexico border in ways that pay homage to those sites’ Indigenous histories and reveal the struggles experienced by those who live around, and seek to cross, such borders. They activate occupied lands using methods ranging from performance and collaboration to sculpture and painting.

Essays and videos about borderlands and occupations

Tanya Aguiñiga, Metabolizing the Border: Binational artist Tanya Aguiñiga pushes the power of art to transform the United States-Mexico border from a site of trauma to a creative space for personal healing and collective expression.

Read Now >

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Border Tuner: Lozano-Hemmer embarks on his most ambitious project to date: an enormous intercom system at the border between El Paso and Juárez that allows participants from both sides to speak and listen to each other via radio-enabled searchlights.

Read Now >

Julie Mehretu, HOWL, eon (I, II): Mehretu rethinks American landscape painting by merging its sublime imagery with the harsh realities not depicted.

Read Now >

Richard Misrach, Border Cantos: Photographer Mirach recounts his work, from his early political aspirations in the 1970s to his current series about left-behind artifacts along the U.S.-Mexico border wall.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Histories of Place

Settler colonialism is a specific form of political occupation wherein an outside population seeks to displace and re-place the Indigenous inhabitants of a colonized territory. Such histories are foundational to the contemporary formations of countries including the United States, Canada, South Africa, and Australia, among others. Often, colonial-era works of art and literature envision the landscapes of these territories as empty spaces that were free to be settled (or were divinely sanctioned to be occupied, as in the concept of Manifest Destiny). The histories and cultures of Indigenous peoples were often rendered invisible in this process.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Earth’s Creation, 1994, synthetic polymer paint on linen mounted on canvas, four panels (private collection)

In this section are works by contemporary artists who intervene in these narratives and instead represent Indigenous relationships to occupied lands. They include examples such as Edgar Heap of Birds’ site-specific interventions, which identify the First Nations that inhabited the land now known as Arkansas before it was settled by Europeans, or Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s abstract paintings, which are inspired by Aboriginal ritual “dreamings” and have roots in ceremonial sand paintings. Many works utilize, or subvert, Western-style maps—which assert ownership through the definition of geopolitical borders and territories—to not only challenge mainstream narratives surrounding the sovereignty of occupied or colonized places, but also compel us to learn more about alternative ways of knowing and inhabiting these regions and their landscapes.

Essays and videos about settler colonialism and Indigenous histories of place

Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Native Hosts (Arkansas): Signs to guide historical understanding.

Read Now >

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People): Smith created this in 1992, responding to the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in North America.

Read Now >

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Earth’s Creation: The painting documents the lushness of the “green time” that follows periods of heavy rain, and makes use of tropical blues, yellows and greens.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Waterways and Maritime Ecosystems

One of the most pressing issues today is the ecological impact of human industry on earth’s natural environment. Artists have found creative ways to visualize this impact, and compel viewers to be more aware of issues such as pollution, sea level rise, global warming, and sustainability. This section includes the works of artists who take different approaches to emphasizing the fragility of our relationship to waterways and marine ecosystems, in particular making sure that oceans, rivers, lakes, and tributaries are included in our definitions and representations of landscape.

Courtney Leonard, ARTIFICE Ellipse, 2016, coiled micaceous clay with glaze, 5 3/8 x 15 x 7 inches (Newark Museum of Art) © Courtney M. Leonard

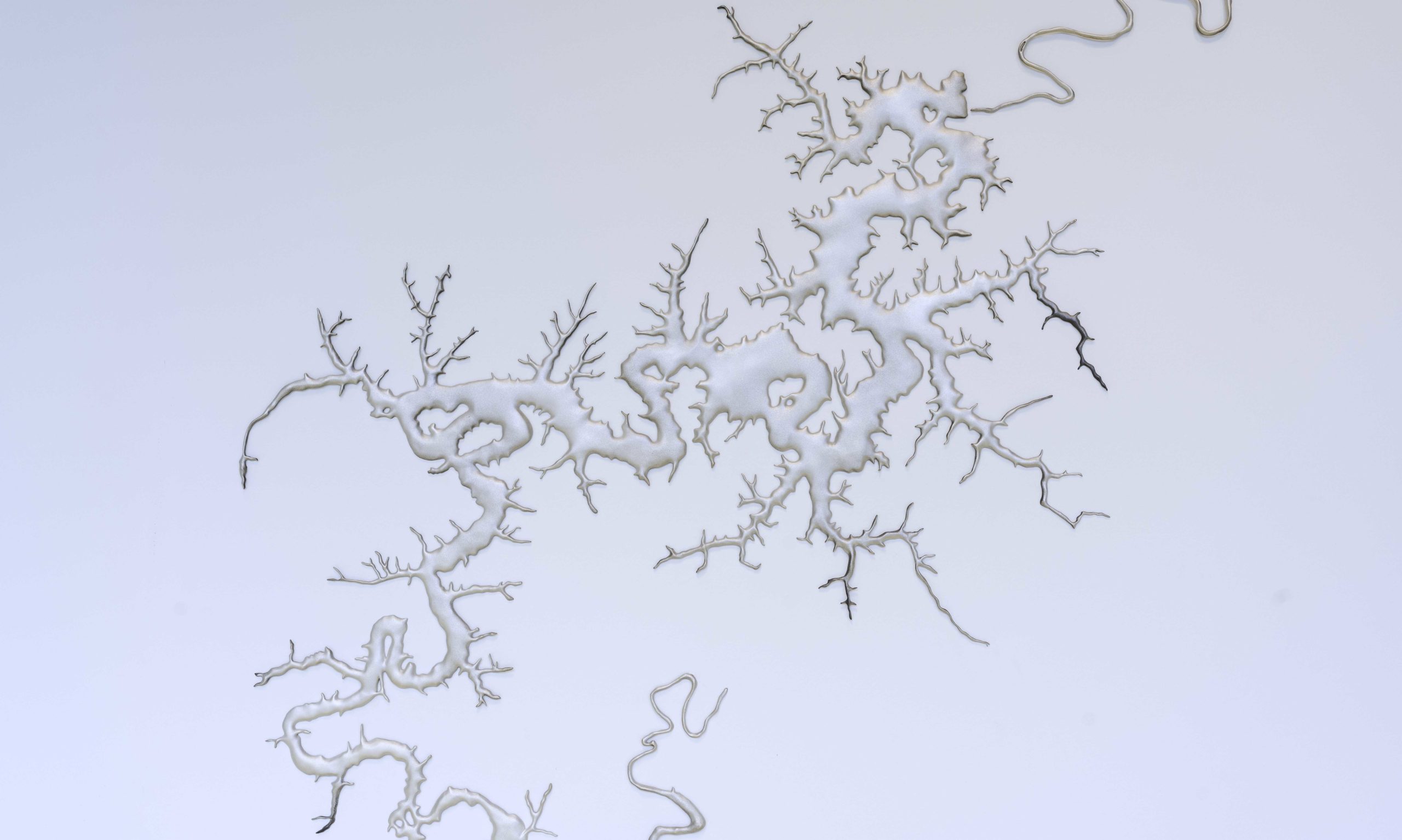

In her sculptural practice, Courtney Leonard, a contemporary artist and member of the Shinnecock nation, focuses on the impact of whaling, coastal erosion, and industrialization on Indigenous ways of life as well as marine species in the coastal Northeastern United States. And in site-specific installations crafted from reflective materials like glass marbles and recycled silver, Maya Lin maps out the serpentine networks of rivers, tributaries, and lakes around the world, usually placing special attention on the water systems that are local to the places where her work is sited. Still others are attentive to mythologies, migrations, and narratives surrounding water, such as Ellen Gallagher’s Water Ecstatic, which represents sea creatures while reflecting on the legacy of the Middle Passage.

Essays and videos about waterways and maritime ecosystems

Minerva Cuevas, Crossing of the Rio Bravo: Cuevas painted a bridge across a riverbed that divides Mexico and the United States.

Read Now >

Luchita Hurtado: Hurtado celebrates her first solo exhibition and discusses how her experience of motherhood and her commitment to environmental activism merge in her most recent body of work.

Read Now >

Maya Lin, Silver Upper White River: The river’s brilliant reflections gave shape to this enormous sculpture of silver.

Read Now >

Nicolás García Uriburu, Coloration of the Grand Canal, Venice: García Uriburu’s playful and innovative approach to painting that involved dying the Venice canals green.

Read Now >

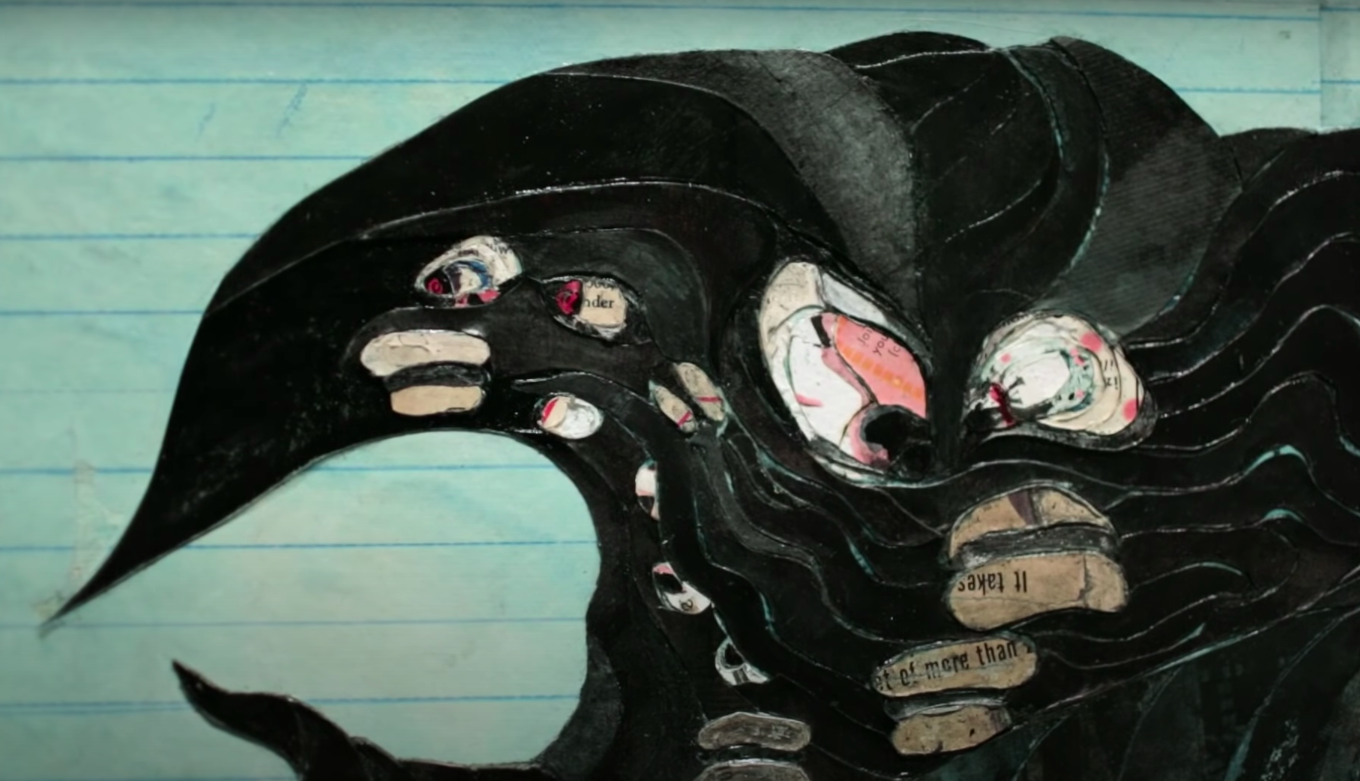

Ellen Gallagher, Cutting: Gallagher’s work often appears abstract and minimal, but upon closer inspection details reveal complex narratives that borrow from maritime history, science fiction, popular culture, and the experiences of African Americans.

Read Now >/6 Completed

Landscapes are defined not just by their topography, but by the political histories, cultural meanings, and personal memories that we associate with them. As this chapter has shown, contemporary artists in the last several decades have found creative and varied ways to represent, critique, and pay homage to our complex relationship with the physical environment.

Notes:

[1] Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8 (Spring, 1979), p. 30.

[2] Art21 Extended Play film, “Julie Mehretu: Politicized Landscapes.”

Key questions to guide your reading

How have artists engaged with and represented the physical environment in ways that are both critical and symbolic of humanity’s complex relationship to the earth?

How have landscapes been “occupied” both in society and in art?

How can artists help us to understand hidden or marginalized histories of place, and compel us to be more respectful of the natural, political, and social ecosystems that we inhabit?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow have artists engaged with and represented the physical environment in ways that are both critical and symbolic of humanity’s complex relationship to the earth?

How have landscapes been “occupied” both in society and in art?

How can artists help us to understand hidden or marginalized histories of place, and compel us to be more respectful of the natural, political, and social ecosystems that we inhabit?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Aboriginal

borderlands

colonization

earthworks

Eco-Art

environmentalism

Indigenous

Land Art

landscape

Manifest Destiny

migration

settler colonialism

site-specificity

Learn more

Learn more about earthworks like the Pyramids of Giza, the Nazca Lines of Peru, and the Great Serpent Mounds of Ohio

More on Manifest Destiny and the displacement of Indigenous societies

Thomas Moran’s Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and the myth of emptiness