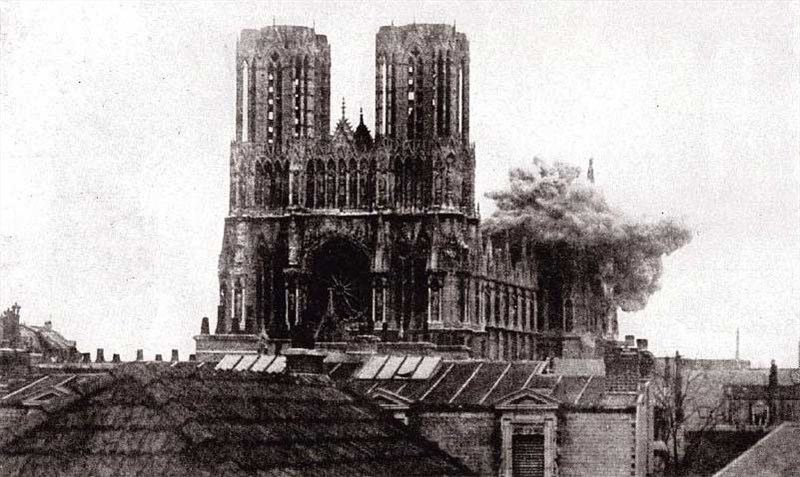

Shell bursting on the cathedral at Reims, from Collier’s New Photographic History of the World’s War, 1918

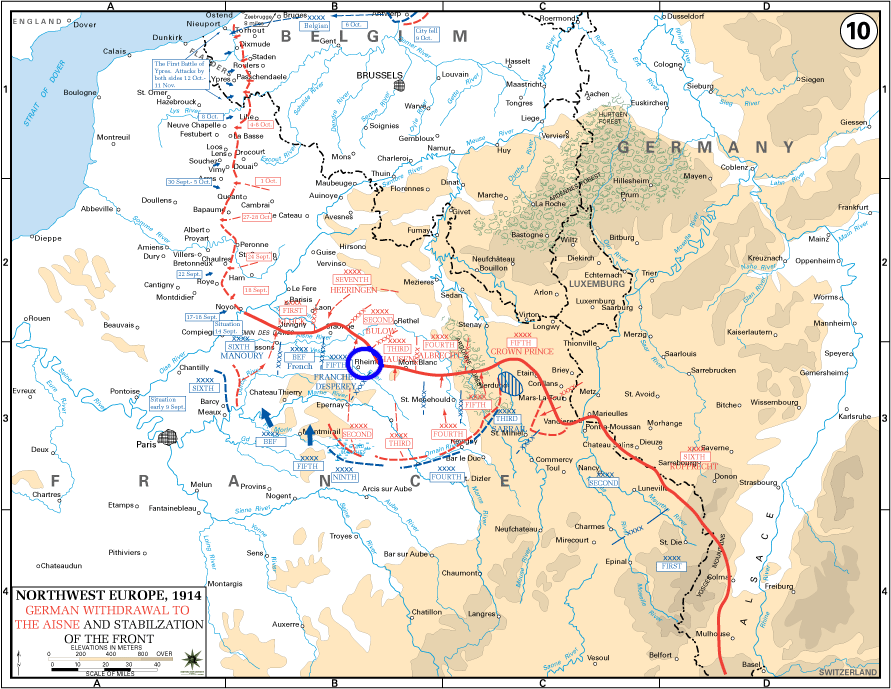

Map of the Western Front, 1914, with Reims circled in blue (map: The History Department of the United States Military Academy, CC0)

The facts…?

World War I officially started July 28, 1914. Originally it was believed that the “situation” would clear itself up by no later than Christmastime. Instead, it took over four long and grueling years, and resulted in more than 15 million deaths. Early on in the conflict, the German army moved into northeastern French territory. This was the beginning of the Western Front. The expeditious land grab by the Germans included the city of Reims. Reims had a well-established history, from its days as a bustling hub of the Roman Empire, to becoming a center of French culture in the early Middle Ages. Additionally, Reims was the “Coronation Capital,” so to speak, the traditional location for the coronation of French kings. It was also home to a magnificent high Gothic cathedral, Notre-Dame de Reims. By early September, the French had forced the Germans to retreat and though the French regained the town, the Germans stayed close by for the entirety of the war.

View of Reims cathedral over the rooftops of the city in 2014 (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

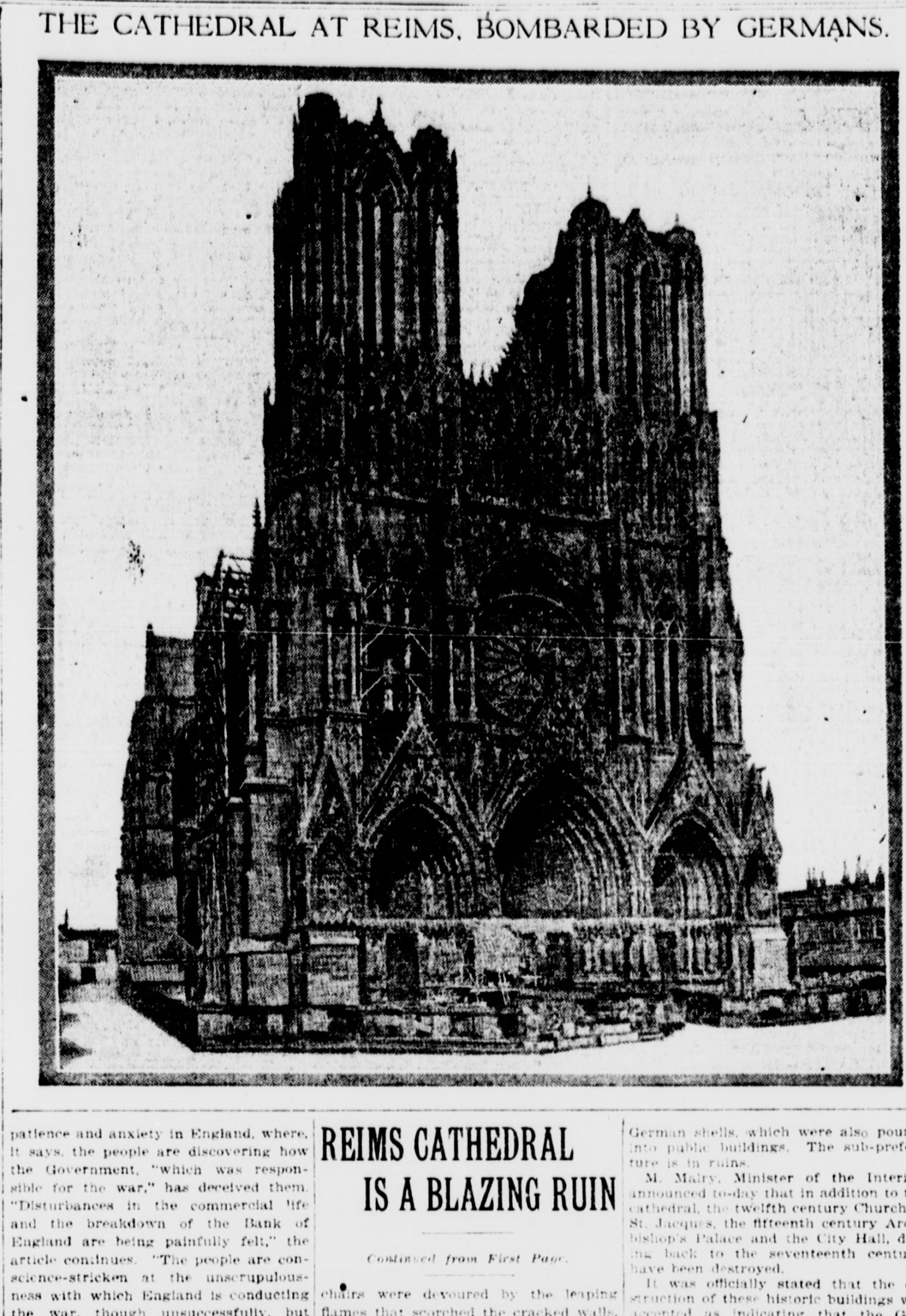

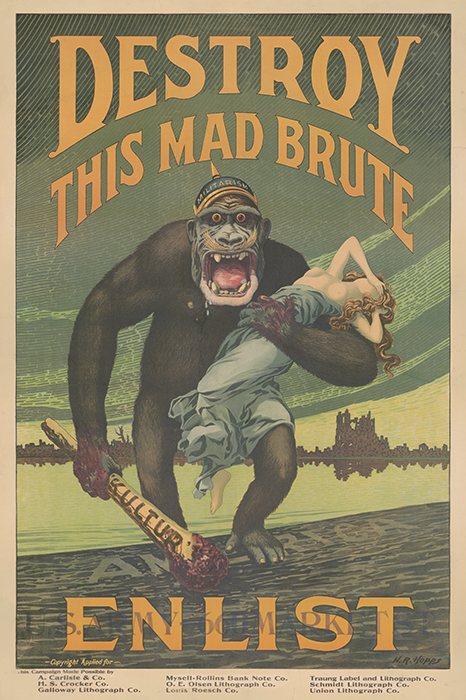

The city of Reims saw significant destruction, and both civilian and military casualties. But no event ignited indignation as did the bombing of the much-venerated Notre-Dame de Reims. The cathedral was first hit by shell fire on September 19th, 1914. Wooden scaffolding that was in place for ongoing repairs caught fire, and contributed to the damage, as did several smaller fires that resulted from the attack. Though the cathedral would be struck again and again as the war continued, it was this initial shelling that sparked a firestorm of outrage, horror, and prodigious propaganda—surely here was damning proof that the Germans were indeed “barbarians,” so lacking in culture themselves that they were compelled to destroy the beauty of another culture out of sheer spite and jealousy. The propaganda insisted that there was no reason to bomb the church since it had no strategic military value, and was a place of sanctuary. The French and their allies stressed that there was no justification to shell the cathedral especially given that was being used to house the wounded (mainly German soldiers callously left behind by their fleeing brothers-in-arms).

“Reims Cathedral is a Blazing Ruin,” The Sun (New York City), September 21, 1914 (Library of Congress)

War crimes

It was acknowledged, even at the time, that the Germans were committing more horrendous acts than the bombardment of Reims Cathedral. So why should a building create more outcry and indignation than the killing of innocent civilians, or other kinds of wartime savagery? Perhaps it was in part that the cathedral, literally meaning the seat of the bishop, could be seen as representing the French nation as a whole, its cruciform shape evoking a sacrificial body. Or, on a more practical note, it was a story that could be easily sensationalized and discussed ad infinitum—cultural war damage was far easier to get past the censors. In the words of Maurice Landrieux, a former priest at Reims but later the Bishop of Dijon “…but it was the most ignoble, because it was at once sacrilegious and stupid, and because it reveals, by its uselessness, the blackest depth of German misdoing.” There was a pervasive belief that the Germans had come to France with the express intention of destroying the cathedral from the outset of the war.

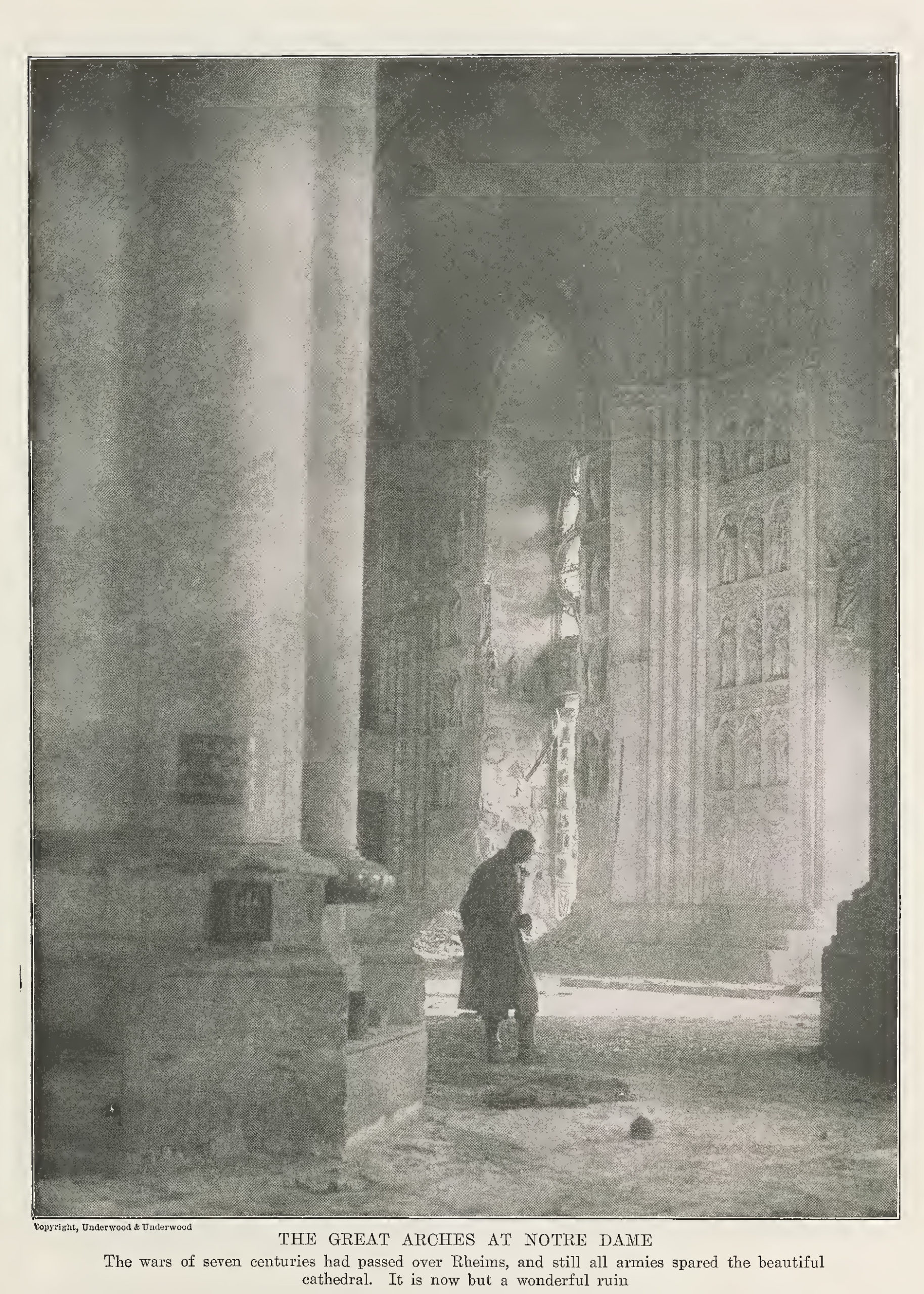

“The great arches at Notre Dame: The wars of seven centuries had passed over Reims, and still all armies spared the beautiful cathedral. Is is now but a wonderful ruin.” from Collier’s Photographic History of the European War, by Francis J. Reynolds and C. W. Taylor, c. 1917

There are two sides to every story, and so it is here. The Germans did shell the cathedral—that is irrefutable. Their explanation as to why they did so was wildly at odds with the French account, and they claimed to be horrified just as deeply as the French, at the damage done to this architectural masterpiece.

The French story was that is that the Germans, before their hasty retreat, had covered the floors of the cathedral with straw, to make it more combustible and that they intentionally left their wounded knowing they would be brought into the church by the French to be tended. A Red Cross flag was raised, a further signal that the cathedral was off-limits as a military target. However, the Germans later claimed the cathedral was being used for military intelligence: a signal station, telephone equipment, and an observation post had been espied in one of the towers during a German fly-by—along with a large cache of weapons. If true, according to international law, the cathedral was a viable military target—a wolf wrapped in sheep’s clothing.

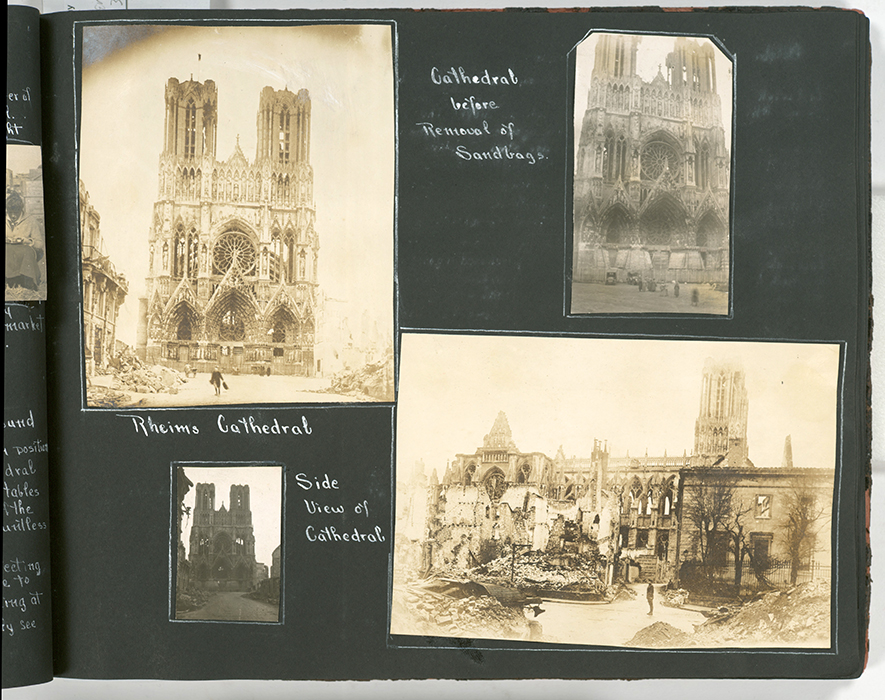

“Cathedral before removal of sandbags (upper right); Reims Cathedral; side view of cathedral” (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

The church was severely damaged—roofs had burned, statues melted, stonework was no longer viable, and more. Nonetheless, the structure was still essentially in good condition after the attack, all things considered. The local French authorities were actually taken to task by their own administrators for not doing a better job putting out the fire, which caused the majority of the damage. The Germans claimed it pained them to commit such an act, but the cunning French had left them no choice. These claims gained little traction.

The result was that—for the French—the German reputation for philosophical thought and general erudition, were suddenly erased—they were viewed once again as one of the “barbarian hordes” of the migration era. German art historians were quick to point out they had been one of the primogenitors of that discipline, and they highly appreciated art from around the globe. German art historians and professors were even dispatched to the front, joining various army units to help provide protection to valuable art on both sides, but to no avail. The mud would not unstick.

Harry R. Hopps, Destroy this mad brute Enlist – U.S. Army, 1918, color lithograph, 106 x 71 cm (Library of Congress)

Culture wars

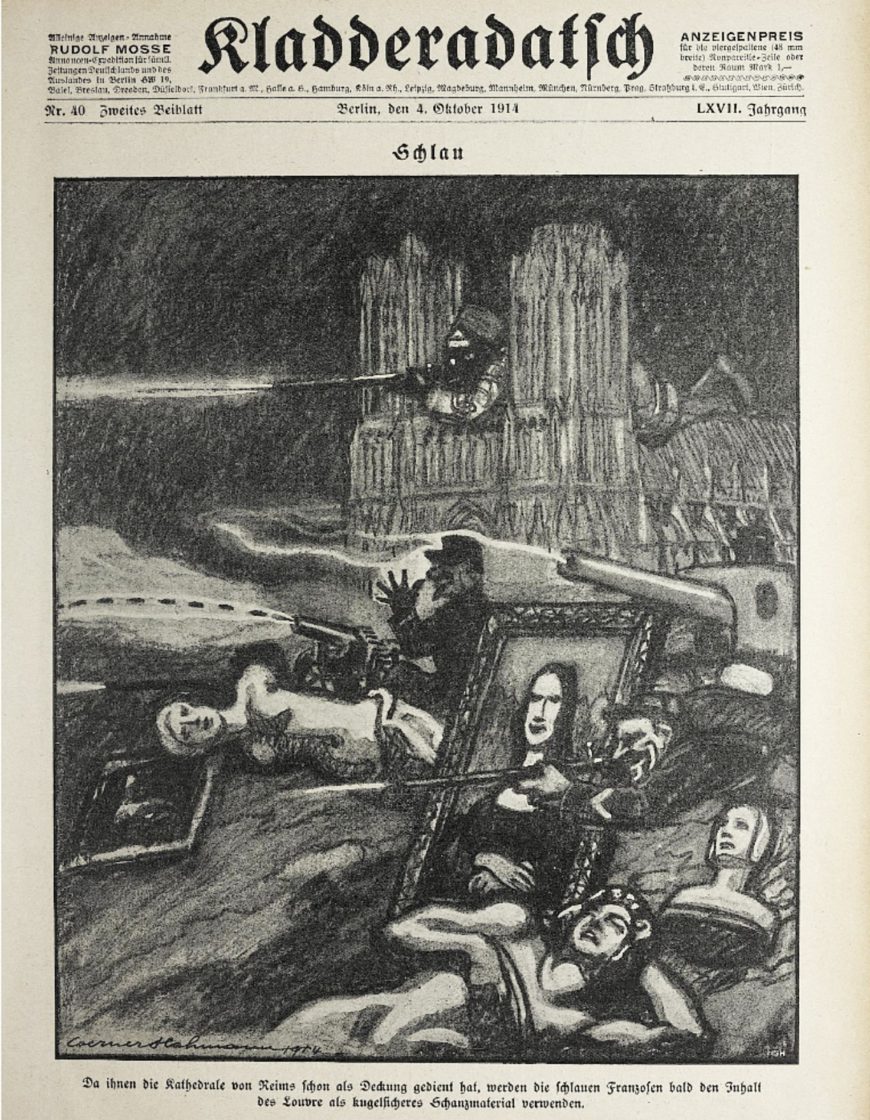

Reims Cathedral continued to be used as propaganda for the whole of the war. Its burnt image was printed on posters and postcards. German soldiers were depicted gun-wielding and slavering at the jaw to seeking to destroy the next great work of art they saw. Meanwhile, the Germans lampooned the French, accusing them of using their own great works of art for nefarious ends without compunction. One well-known cartoon read, “The cunning French have used Reims cathedral as a shooting platform—next they’ll be building trenches with the contents of the Louvre.”

“The cunning French have used Reims cathedral as a shooting platform—next they’ll be building trenches with the contents of the Louvre,” Werner Hahmann, Schlau (Sly), from Kladderarsch, no. 40 (cover, October 1914)

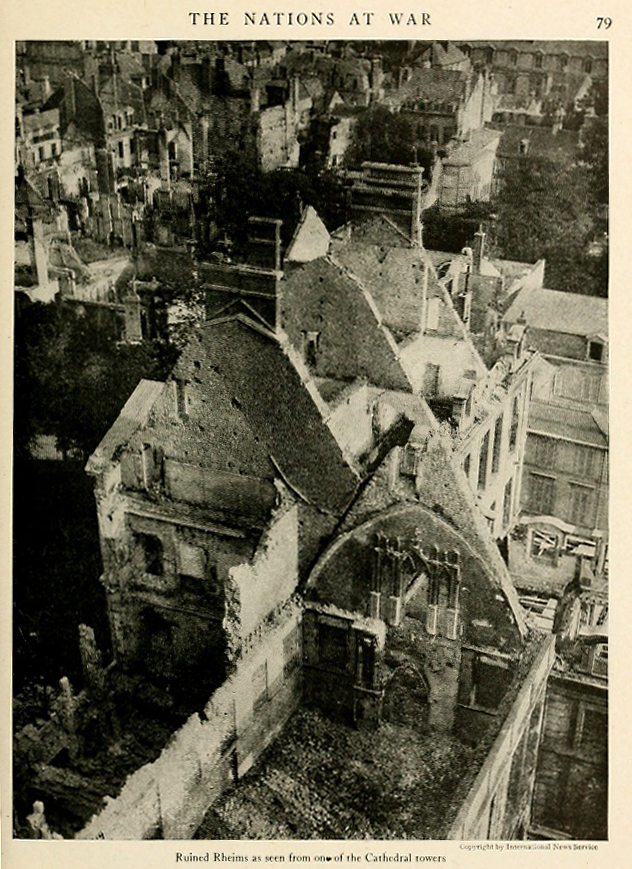

Beyond the trenches, the battle for cultural superiority was on. The French had the upper hand when it came to the events at Reims that fateful night. They could claim eyewitnesses, and they also photographed the cathedral in ways intended to most incite a viewer.

“Ruined Reims as seen from one of the Cathedral towers,” from The Nations at War by Willis John Abbot, 1917

The Germans did try hard though, despite their lack of handy visual evidence, to underscore that they had been the only country to carry out any form of art protection. Kunstschutz (the German term for the principle of preserving cultural heritage and artworks during armed conflict) was said to protect art on both sides of the war. It was even said to be endorsed by Kaiser Wilhelm II himself. The Germans emphasized that the bombing of the cathedral at Reims had not been part of a systematic effort, instead, it was one of the many sad byproducts of the war.

E. Lemielle, Souvenez-vous! 1914. Rien d’Allemand!!! Des Allemands (Remember! 1914. Nothing German! Nothing from the Germans), 1919, color lithograph, 83 x 60 cm (Library of Congress)

Neither side held back, each was determined to show that while one was on the side of the angels, the other was ruthlessly attempting to profit by the destruction of art. Meanwhile, the Germans claimed that as they were the creators of the Gothic style, and so the cathedral was just as much part of their cultural heritage as it was France’s, and they again attempted to remind the world of their integral role in the creation of art history. Again, this gained no traction with the French, nor with most nations.

“The cathedral of Notre Dame at Reims, after repeated bombardments,” from Collier’s Photographic History of the European War, by Francis J. Reynolds and C. W. Taylor (c. 1917)

By the end of the war Reims, which had been targeted multiple times, was the ruin the French had claimed after the initial attack. The continued attacks on the cathedral called into doubt the veracity of the Germans’ initial account. After the first bombardment, it was certain that the cathedral was no longer being used for any military purpose—if it ever had been. Again, a cultural landmark of this kind could only become subject to brute force with good reason, so the continued bombing only furthered the French position of German brutality and outright vandalism. J.W. Garner, in his International Law and the World War, states, “Monuments of this stature are not only entitled to respect because of their sanctity but are especially protected because of the Law of Nations” (p. 445).

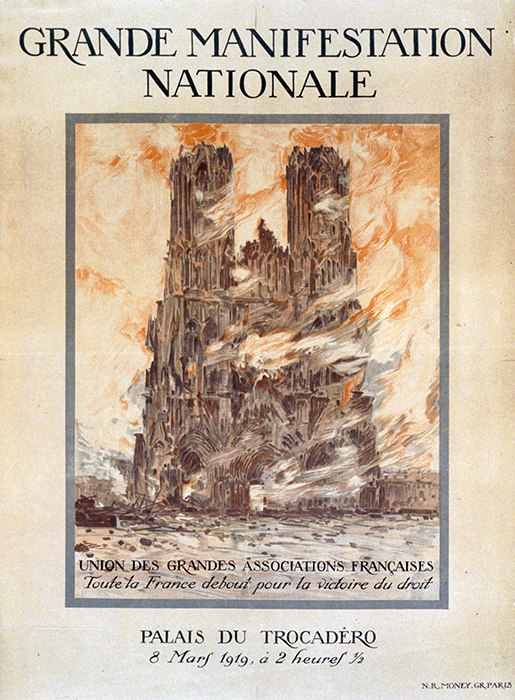

Grande Manifestation Nationale, 1919, color lithograph, 80 x 59 cm (Library of Congress)

Restoration on the cathedral began almost immediately after the end of the war, funded in part by the Rockefeller family. The cathedral reopened in 1938, though work continues to this day. Recently, the world looked on aghast when, in April of 2019, the iconic Notre-Dame de Paris burned. Even more recently, the lesser-known Cathedral of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in Nantes, another Gothic jewel, caught on fire. In these cases there appears to be no terrorism involved, only age and human error. Perhaps then, the. most important take-away from the bombing of Reims Cathedral is that blame is, to a degree, irrelevant, at least after the fact. The real lesson is that we must do better at preserving our cultural heritage the world over.

Marc Chagall, stained glass windows replacing war-damaged ones, Reims Cathedral, 1967-1985 (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Additional resources