Auguste Rodin, The Age of Bronze (L’Age d’airain), modeled 1876, cast by Alexis Rudier c. 1906, bronze, 182.9 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Auguste Rodin’s The Age of Bronze, first exhibited in 1877, marked a turning point in the artist’s career and practice. With this expressive sculpture, Rodin began to distance himself from the long academic tradition of depicting highly idealized figures drawn from religious, mythological, or historical subjects. The figure in The Age of Bronze has fully shut eyes and a half-open mouth as if he is awakening.

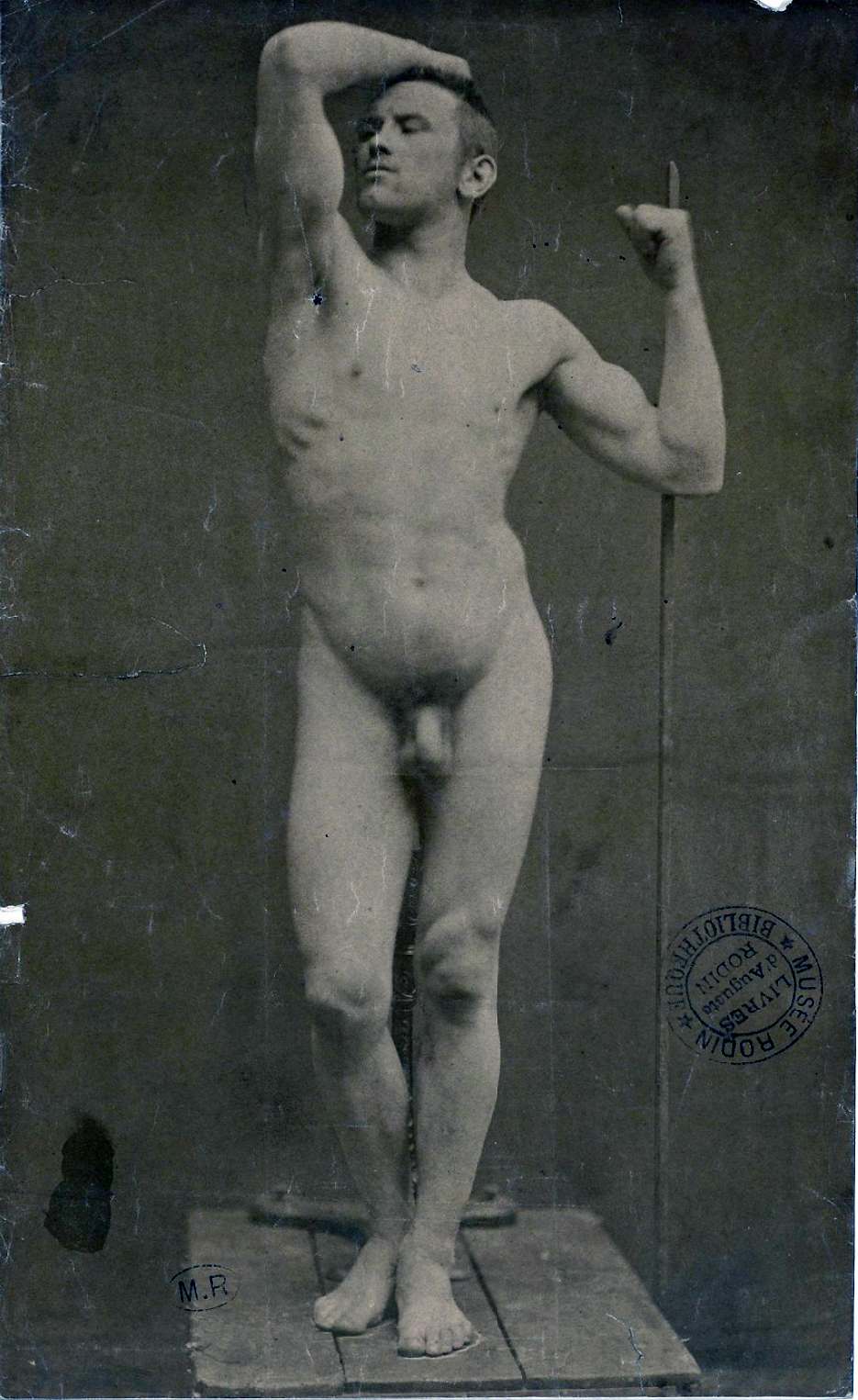

The sculpture was initially titled The Vanquished and the Wounded Soldier and also became known as The Awakening Man. Archival photographs (see above) and an early drawing show that while posing for Rodin, the model initially held a spear in his raised left hand.

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer) or Canon , Roman marble copy of a Greek bronze, c. 450–440 BCE (Museo Archaeologico Nazionale, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

By removing the shaft, Rodin deliberately abandoned specific iconographic references in favor of depicting the abstract idea of awakening consciousness. It is also possible that the removal of the spear relates to the ancient Greek sculpture, Polykleitos’s Doryphoros. The multi-layered title, The Age of Bronze pays tribute broadly to human ingenuity—specifically the development of bronze following the use of stone tools, a milestone in mankind’s development. However, the rejection of explicit narrative could be explained by the political context in Paris in 1877 with the renunciation of French Republican values by the Bourbon and Orléans royalists.

Auguste Rodin, The Age of Bronze (L’Age d’airain), modeled 1876, cast by Alexis Rudier c. 1906, bronze, 182.9 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Observing nature

The Age of Bronze was the first major sculpture to bring Rodin public notice. The model for the sculpture was Auguste Neyt, a 22-year-old Belgian soldier (see photograph above). Rodin worked and reworked the preliminary clay sculpture more produced by molding over a period of eighteen months through the end of 1876, with a month spent in Italy from February through March 1876 to study the works of the Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo. The delicate contrapposto of the figure is a tribute to ancient Greek and classicizing Renaissance sculpture. The figure’s right leg is bent, standing with most of his weight on his left leg.

Michelangelo, The Dying Slave, 1513–15, marble, 2.09 m high and usually considered unfinished and originally intended for the tomb of Pope Julius II (Musée du Louvre)

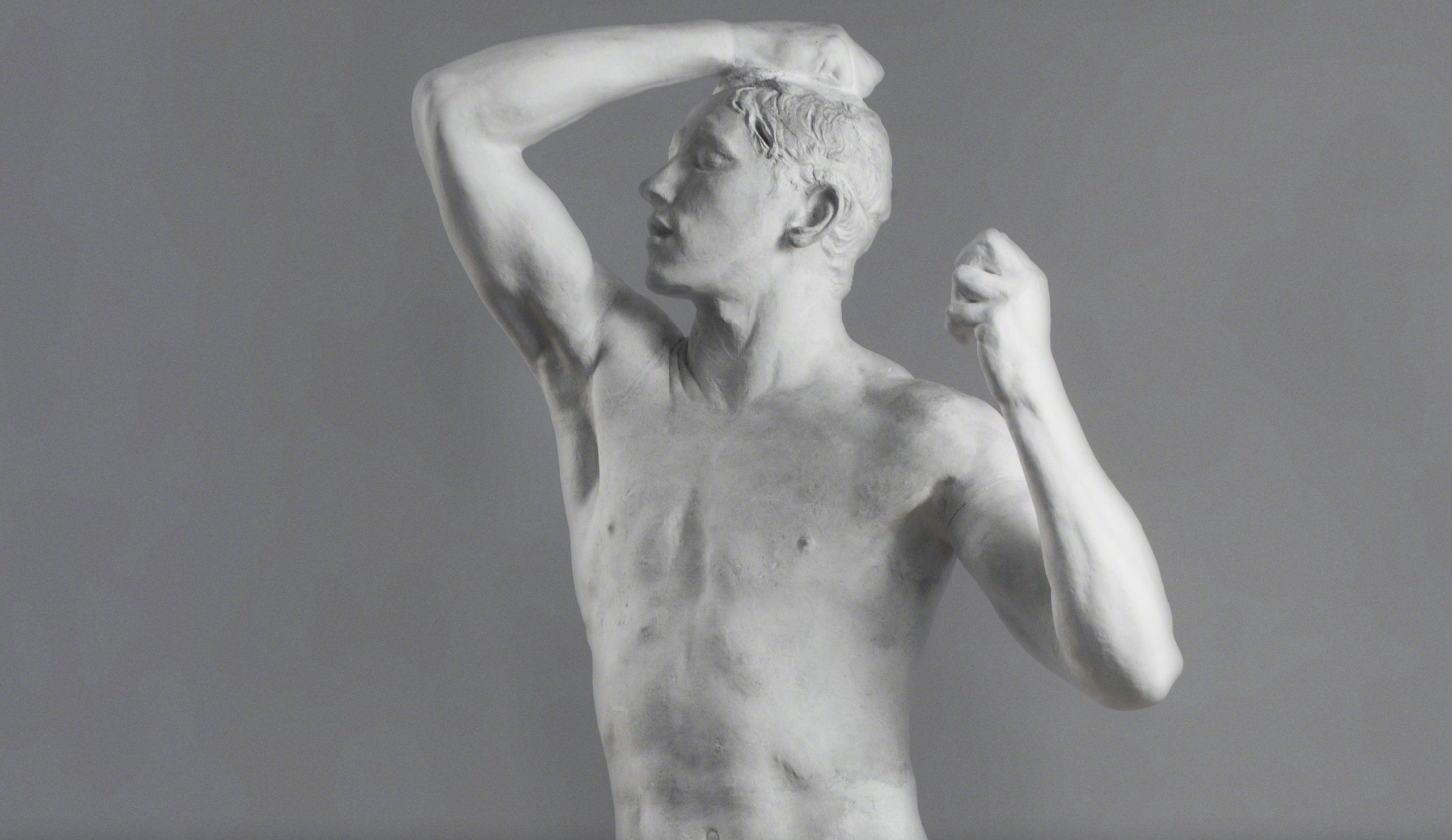

The pose with the elbow raised above the head partly derives from Michelangelo’s Dying Slave (above), a sculpture Rodin had studied in the Louvre. Rodin applied his theory of the profiles based on the study of successive contours that would allow him to remain true to nature. Instead of a unique viewpoint, he would strongly encourage viewers to go around the sculpture and fully engage with it from every angle.

Controversy and innovation

The work in plaster was first exhibited in Brussels in January 1877, where it was acclaimed for its life-like quality, then at the Spring Salon in Paris, where it caused controversy. The sculpture was so life-like that the Salon’s jury accused Rodin of having it cast directly on the live model, which was considered a dishonest artistic practice. Academic sculpture favored idealized over realistic forms. Because of the conservative nature of academic sculpture at the time, fidelity to the beauty of the human form was valued as the result of study and practice, not as an automatic process of direct casting.

Auguste Rodin, The Age of Bronze (L’Age d’Airain), modeled 1875-1876, cast 1898, plaster, 180 x 71.1 x 58.4 cm (photo: takomabibelot, CC BY 2.0, The National Gallery of Art)

Rodin made available to the skeptical jury photographs by Gaudenzio Marconi of his model in the same pose for a juxtaposition and comparison, proving he had actually modeled the figure by hand. Thanks to the use of documentary photography, Rodin managed to clear his artistic reputation. The French state acquired the sculpture and paid to have it cast in bronze. By attracting the attention of both the officials of the arts administration and the public, Rodin transformed this scandal into success and three years later he obtained the prestigious commission for what would become The Gates of Hell, the design of bronze doors for a future museum of decorative arts in Paris. The Age of Bronze was exhibited more than thirty times in Rodin’s lifetime, more often than any of his other sculptures. It became increasingly popular among museums and collectors and it was cast in bronze in different dimensions (small, medium, and large), both during Rodin’s lifetime and posthumously.

Auguste Rodin, The Age of Bronze (L’Age d’airain), modeled 1876, cast by Alexis Rudier c. 1906, bronze, 182.9 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Founder of Modern Sculpture

The Age of Bronze marked a turning point in Rodin’s career and practice, a departure from the academic rules of the 19th century towards what will become the modern sculpture of the 20th century. In 1903, the young Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who later became Rodin’s secretary, wrote an influential book on Rodin, pointing out that The Age of Bronze “indicates in the work of Rodin the birth of gesture”, Rilke seeing in the face “that pain of a heavy awakening.” The Age of Bronze made a critical turn in Rodin’s practice as he abandoned traditional academic iconography in favor of modern concepts and aesthetics. In 1905, in a conversation with the poet and art critic Camille Mauclair, Rodin explained his artistic process: “I began by very faithful studies of nature, as in The Age of Bronze. Then I understood that it was necessary to raise one’s self to a higher level, which is the interpretation of nature by a temperament. Thus I have been led to the logical exaggeration of forms, to the research into character, to its reasoned amplification. I have understood the necessity of sacrificing a detail of a figure to its general geometry, or that part to a synthesis of its aspect.” In fact, the American sculptor and author Truman Bartlett interpreted The Age of Bronze as an allegorical self-portrait.