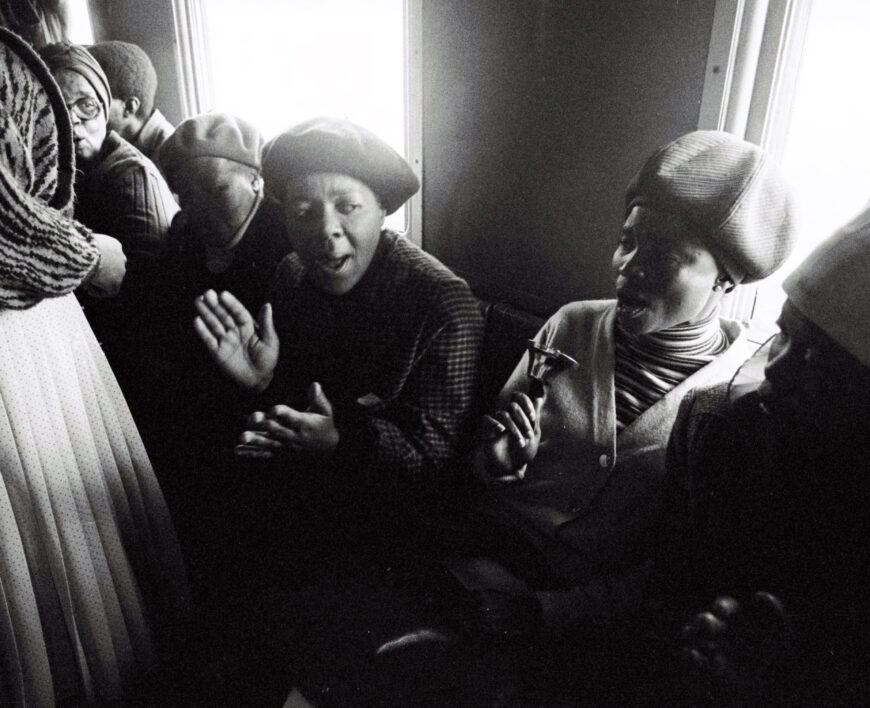

Santu Mofokeng, “Opening Song, Hands Clapping and Bells,” from the series Train Churches, 1986, gelatin-silver print, 19 x 28.5 cm (The Walther Collection) © Santu Mofokeng

Have you ever taken public transportation, such as the train or subway? If so, perhaps you have experienced the dilemma of selecting which empty seat to take before all the good ones are unavailable. Or on the flipside, you might have experienced the rush of passengers trying to find an empty seat, and you have had to stand since it was so crowded. And maybe you have encountered people at the stations who are not commuting or traveling, instead selling foodstuffs and drinks, handing out pamphlets to advertise services or businesses, or entertaining passengers by playing musical instruments or singing songs.

Perhaps when you were on the train or subway, you have had the experience of seeing a passenger preach from the Bible or pray. And you might have heard other passengers worship by singing and clapping in unison, or by using instruments or the walls of the train or subway car as a drum to make music. These latter situations were part of train travel in South Africa in 1970s–80s for Black passengers, and captured in the black-and-white photographs of Santu Mofokeng’s photo-essay, Train Churches. [1] Mofokeng was one of the passengers who traveled by train to get to work and witnessed other passengers engaged in worship. As the title suggests, his photo-essay shows people preaching, praying, healing, dancing, and making music while commuting, turning the train cars into churches.

In one photograph, Opening Song, Hands Clapping and Bells, the viewer sees six passengers seated along one side of the train. [2] Although there is light coming from the windows of the train car, the light seems to conceal, rather than reveal, the details in the photograph. Largely obscured by shadows, the foreground is difficult to discern, save for the woman at the far right. In the middle of the photograph, the viewer sees two women singing; one is in the process of clapping her hands, while the other is ringing a handheld bell. To the left of these women are four other passengers: a woman whose face is obscured by shadows, another woman wearing glasses who appears to be singing, and two other passengers whose faces the viewer cannot see. One of these passengers is blocked by the woman wearing glasses, while the other passenger is standing, but cropped out of the frame of the picture except for her long skirt and jacket. The closeness of the seated passengers and cropped figure of the standing passenger give us a sense of how crowded it was inside the train car.

Train travel during apartheid

Comprised of ten photographs, Train Churches documents the commute of Black South African passengers taking the train during apartheid in South Africa. They are commuting from their homes in the township of Soweto to work in the urban center of Johannesburg, which was set apart for white South Africans. Under apartheid, Black South Africans were forced to live in townships or Bantustans so that they would be separated and excluded from white South African spaces. However, major urban areas set aside for white South Africans relied on the labor provided by Black South Africans, allowing the latter to work in these areas in the day but requiring them to leave at night. Trains enabled Black South African passengers to commute daily to work, but they served to segregate them from other South Africans.

Traveling by train was tiring, stressful, and unsafe. Train cars were packed and overcrowded, and spaces where criminal activity and violence occurred. In spite of the difficulties and dangers associated with train travel, the train cars were places where some passengers engaged in worship activities, as we can see in the women singing and making music in Opening Song, Hands Clapping and Bells. As these passengers worship together, rather than individually, they create a sense of community in the space of the train car.

Worship as resistance

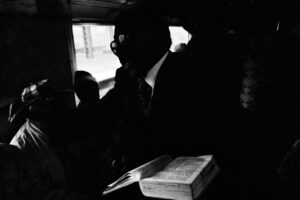

Santu Mofokeng, “The Book, Johannesburg—Soweto Line,” from the series Train Churches, 1986, gelatin-silver print, 19 x 28.5 cm (The Walther Collection) © Santu Mofokeng

Trains contributed to the apartheid regime’s aim to segregate Black South Africans from white South Africans, and so the act of engaging in religious or spiritual activities on the train has been interpreted as a form of resistance. Although Mofokeng himself has admitted that he is ambivalent towards religion and spirituality, he recognized that maintaining and practicing one’s faith helped people to cope during apartheid. The apartheid government endeavored to relegate Black South Africans to second-class status by stripping them of their freedoms and rights. However, Black South Africans protested implicitly by asserting their humanity through worship. In Train Churches, Mofokeng records slices of township life that are neither out of the ordinary nor sensational, as worship in the space of the train had been occurring since the 1970s.

Documenting life under apartheid

In the 1950s-60s, the South African magazine, Drum, featured the work of Black South African photographers who documented township life under apartheid. These Drum photographers, such as Peter Magubane influenced Mofokeng when he was growing up in Soweto. When he got a camera at the age of 17, Mofokeng started practicing as a street-photographer. He got a job as a darkroom assistant at a pro-government newspaper, which followed governmental policies closely and did not promote Black South Africans to higher positions such as technician and photographer. He also learned about photography by reading books on the subject that were available to him. After leaving his job as a darkroom assistant, he became a photographer’s assistant at an advertising firm. He was mentored by white South African photographer, David Goldblatt, who took documentary photography. Mofokeng has mentioned that Goldblatt’s mentorship was invaluable to him and that he enjoyed his style of photography. On the surface, Goldblatt’s photographs seem objective and apolitical, but they show how apartheid impacted life for South Africans.

In 1985, Mofokeng joined the Afrapix Collective, a group of Black and white South African photographers that documented the struggle against apartheid in conjunction with anti-apartheid organizations. The distribution of their photographs helped elicit local and international responses against the apartheid regime’s oppression of Black South Africans. However, Mofokeng has pointed out that he was more interested in documenting mundane, ordinary life in the township rather than taking struggle photography, which was more common for members of the Afrapix Collective. For Mofokeng, struggle photography was limited and did not reflect the fullness of township life—portraying Black South Africans as perpetual victims.

After quitting his job as a photojournalist for an alternative newspaper, Mofokeng joined African Studies Institute (now called Institute for Advanced Social Research, or I.A.S.R.) in the Oral History Project at the University of Witwatersrand, which gave him specific photographic assignments (that were not the struggle photography that he became critical and wary of) and encouraged him to explore his own photographic projects. Among these personal projects was Train Churches.

When it was published, Mofokeng introduced it with a brief text:

Early-morning, late afternoon and evening commuters preach the gos-

pel in trains en route to and from work.

The train ride is no longer a means to an end, but an end in itself as

people from different townships congregate in coaches—two to three per

train—to sing to the accompaniment of improvised drums (banging the

sides of the train) and bells.

Foot stomping and gyrating—a packed train is turned into a church.

This is a daily ritual.[3]

Apart from this text, Mofokeng does not give the viewer many additional details about the photo-essay, the people photographed, and his relationship to them. Furthermore, it is unclear if these photographs were taken during a single commute or several. However, the content of the photo-essay reflects a departure from struggle photography, as Mofokeng aimed to show the viewer a different and fuller picture of township life apart from distress and despair.

Notes:

[1] This photo-essay is also referred to as “Train Church” or “Church Train” in other articles.

[2] It is unclear if Mofokeng gave titles to individual photographs from Train Churches. When it was published, Train Churches was accompanied by an introductory text and three captions.

[3] Santu Mofokeng, “Train Churches (photo-essay),” TriQuarterly 69 (1987): p. 352.

Additional resources

David Alvarez, “Train-Congregants and Train-Friends: Representations of Railway Culture and Everyday Forms of Resistance in Two South African Texts,” Alternation 3, no. 2 (1996): pp. 102–29.

Patricia Hayes, “Santu Mofokeng, Photographs: ‘The violence is in the knowing,’” History and Theory 48, no. 4 (2009): pp. 34–51.

David L. Krantz, “Politics and photography in apartheid South Africa,” History of Photography 32, no. 4 (2008): pp. 290–300.

Santu Mofokeng, “Train Churches (photo-essay),” TriQuarterly 69 (1987): p. 352.

Santu Mofokeng, “Trajectory of a street photographer,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 11, no. 1 (2000): pp. 40–47.

Paul Von Blum, “Resistance, Memory, and Hope: The Photographic Art of Peter Magubane,” Safundi: The Journal of South African and American Comparative Studies 6, no. 4 (2005): pp. 1–14.

Annabelle Wienand, “Santu Mofokeng: Alternative ways of seeing (1996–2013),” Safundi 15, no. 2-3 (2014): pp. 307–28.